AmandaHoang

advertisement

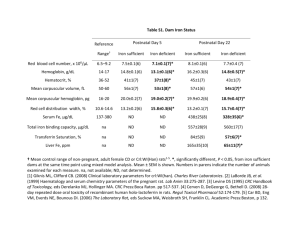

Iron is a mineral found in the dirt on the ground –not that we should be eating mud, but rather sources that come from the earth. I chose was iron as my nutrient of study mainly because I have recently begun looking into having a more vegetarian diet and I remembered reading that vegans and vegetarians have a greater risk for iron deficiency. In actuality, those who choose to live on a plant-based diet do truly need 1.8 times the normal requirement! The requirements for iron are based on several key factors that greatly influence its function in the body. Some of these functions include playing a vital role in metabolic reactions, as well as being an essential component of hemoglobin and transporting oxygen in the blood to the body’s tissues and organs. In order to elucidate the necessity of this mineral in the diet, Dietary Reference Intakes have been established to ensure adequate intake levels for the population as a whole. However, as with vegetarians, certain subgroups of the population have additional needs that must be meet to maintain iron levels for a healthy body. Throughout history, it has seemed that the bright red color of blood piqued the interest of scientists. Through the work of two particular scientists, Sydenham and Willis, which showed that iron salts were able to cure anemia in young women, biochemists found that iron is a “characteristic constituent of blood and is a component of hemoglobin… [Thus] the proof that hemoglobin is an iron protein established the importance of Fe in mammalian nutrition” (1). With the knowledge that iron was essential part of the diet, the importance of making sure that the population had adequate levels of the nutrient was the next step. When one fails to have adequate stores of iron, that individual may face iron deficiency anemia, which is by far the most common nutritional deficiency in the world. Some symptoms include fatigue, rapid heart rate, palpitations, and rapid breathing on exertion; all these result in an impairment of athletic performance and physical work capacity. This decreased ability to function can be attributed to the reduced hemoglobin content in red blood cells, thus decreasing the oxygen delivery to mitochondria in active muscles for enzymes required for electron transport and ATP synthesis Individuals with severe iron-deficiency anemia may result in brittle and spoon-shaped nails, sores at the corners of the mouth, taste bud atrophy, and a sore tongue (2). Functional indicators of iron deficiency also include delayed psychomotor development in infants, impaired cognitive function, and adverse effects for the mother and fetus including premature delivery. Iron status is measured through laboratory tests and can determine the stage of iron deficiency with observations of several indicators. Iron is found in food in two forms, heme and nonheme iron. Animal-based food products such as meat, fish, and poultry are rich sources of heme iron and are highly bioavailable or readily absorbed by the body. However, it consists of only half the iron, as the other half is nonheme and is not as readily absorbed. The absorption of nonheme iron is greatly affected by its own solubility as well as its interaction with the other meal components that may help or hinder uptake. Significant food sources of nonheme iron include fortified breads, cereals, and breakfast bars; other lesser contributors of nonheme iron include dairy foods, eggs, and plant-based foods like fruits, vegetables, and whole grain items such as bread and pasta. Therefore, we can see that the MyPyramid food groups that contribute to iron intake include all categories excluding fats and dairy. As a result of the decreased absorption of iron from plant-based food products, it is been estimated that the bioavailability of iron from a vegetarian diet is only approximately 10%, compared to the normal 18% of a non-vegetarian’s diet. Thus, the U.S. Food and Nutrition Board has set the RDAs for vegetarians at 14mg/day for adult men and postmenopausal women, 33mg/day for premenopausal women, and 26mg/day for adolescent girls (3). According to MyPyramid.gov, “Iron sources for vegetarians include iron-fortified breakfast cereals, spinach, kidney beans, black-eyed peas, lentils, turnip greens, molasses, whole wheat breads, peas, and some dried fruits such as dried apricots, prunes, raisins (4).” Therefore, a plant-based diet should include more quantities of such foods and is recommended to consume them with a source of ascorbic acid to increase uptake in the body. Iron is a significant component of many proteins in the body, including enzymes, cytochromes, myoglobin, and hemoglobin; with over two-thirds of the body’s iron found in hemoglobin (3). Hemoglobin is the protein in red blood cells that carry oxygen from the lungs to various tissues throughout the body, while myoglobin is a protein that aids in the transport and short-term storage of oxygen to muscle and assist in biochemical reactions in enzymes (2). Cytochromes are key players in cellular energy production in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. The amount of iron absorbed by the body is relatively low but directly proportional to the person’s iron stores –if the stores are great, then less iron is absorbed. Iron is absorbed as both heme and nonheme iron in the upper small intestine by an energy-dependent carrier-mediated process. After that, the iron is transported within the cell and transferred to plasma. Since many factors influence iron absorption, only estimates can be given regarding the absorption levels for heme and nonheme iron –25% and 16.8%, respectively (3). The main sites of storage in the body include the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. The iron that is absorbed in the duodenum by enterocytes but not taken up by transferrin, a blood plasma protein for iron delivery, will be excreted in feces. However, very little iron is excreted into urine. Iron intake requirements are set based on factors such as basal iron losses, increased tissue and storage iron, and other indices (3). The following tables demonstrate the recommended relative intakes for various life stage groups. Table 1: Recommended Dietary Allowances for Iron for Infants (7 to 12 months), Children, and Adults Age Males (mg/day) Females (mg/day) Pregnancy (mg/day) Lactation (mg/day) 7 to 12 months 11 11 N/A N/A 1 to 3 years 7 7 N/A N/A 4 to 8 years 10 10 N/A N/A 9 to 13 years 8 8 N/A N/A 14 to 18 years 11 15 27 10 19 to 50 years 8 18 27 9 51+ years 8 8 N/A N/A As the table shows, there is an increased iron need for females who are pregnant due to increased blood volume, increased needs of the fetus, and blood loss during delivery; and for females in the age of menarche because of the increased blood loss during the menstrual flow. Table 2: Estimated Average Requirement for Iron for Infants (7 to 12 months), Children, and Adults Age 7 to 12 months 1 to 3 years 4 to 8 years 9 to 13 years 14 to 18 years Males (mg/day) 6.9 3.0 4.1 5.9 7.7 Females (mg/day) 6.9 3.0 4.1 5.7 7.9 Pregnancy (mg/day) N/A N/A N/A N/A 23 Lactation (mg/day) N/A N/A N/A N/A 7 19 to 50 years 51+ years 6.0 6.0 5.0 5.0 22 N/A 6.5 N/A The increased iron intake need for both male and females occurs around 9 to 18 years, due to a rapid increase in growth that requires more blood and thus more oxygen through hemoglobin transport. Table 3: Adequate Intake for Iron for Infants (0 to 6 months) Age (months) 0 to 6 Males and Females (mg/day) 0.27 The recommended intake is reflective of the average iron intake of healthy breast-fed infants. Table 4: Tolerable Upper Intake Levels for Iron for Infants 7 to 12 months, Children, and Adults Age 7 to 12 months 1 to 13 years 14 to 18 years 19 + years Males (mg/day) 40 40 45 45 Females (mg/day) 40 40 45 45 Pregnancy (mg/day) N/A N/A 45 45 Lactation (mg/day) N/A N/A 45 45 The UL has been set to prevent excessive iron intakes that may result in acute toxicity, secondary iron overload, and gastrointestinal distress, with the latter being the critical adverse effect. Various dietary factors may influence iron absorption, including ascorbic acid, phytate, polyphenols, vegetable proteins, and calcium. Ascorbic acid has been found to strongly enhance the absorption of nonheme iron. Conversely, high levels of the following substances may actually inhibit nonheme iron absorption. Foods such as soybeans and lentils are high in phytate and have shown low levels of iron absorption. Polyphenols, which are found in tea and red wine, were shown to inhibit iron absorption as well. Calcium also inhibits absorption of heme iron as well, through mechanisms not yet made completely clear (3). If one is trying to increase iron absorption, it may not be recommended to consume foods high in phytate, polyphenols, vegetable proteins, or calcium along with a meal with high iron levels. It is not a recommendation to eliminate such foods from the diet but rather an awareness of the potential interactions of substances. Iron can, in turn, affect the absorption of other substances. To be specific, data has indicated that high iron intakes, such as in the form of a supplement, may actually inhibit zinc absorption if taken without food. The current standard of iron intakes is set at a level that is going to meet the needs of the population for this particular nutrient to ensure optimal health and prevention of disease, specifically iron deficiency anemia. Each life stage group as well as gender has been given a particular intake that will supply iron necessary for increased growth, blood loss, or decreased bioavailability. Any higher levels of intake past the tolerable upper intake levels, which may occur with supplements, will result in adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and many other gastrointestinal side effects. It is crucial to understand the level of deficiency before taking supplements to prevent such occurrences. Some current issues and controversies about iron state that iron stimulates the activity of molecules that may inflame and damage coronary arteries and lead to an increased risk for coronary heart disease (5), but there is more research to be done for a conclusive answer. Overall, iron is a nutrient that is readily found in foods that come from both animals and plants. Although animal sources contain amounts of iron at higher level of bioavailability, purposefully chosen plant sources can provide an equally adequate amount to maintain proper iron stores in the body. Vegetarians and omnivores alike can celebrate lifestyles with a knowledgeable, healthful diet without worry of deficiency! References 1. Neilands, J.B. "A Brief History of Iron Metabolism." BioMetals 4.1 (1991): 1-6. Web. 07 May 2010. 2. Higdon, Jane, Victoria Drake, and Marianne Wessling -Resnick. "Iron." Micronutrient Information Center. Linus Pauling Institute at Oregon State Universit y, Aug 2009. Web. 08 May 2010. <http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/minerals/iron/index.htm l>. 3. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Iron. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001: 290-393. 4. "Vegetarian Diets." MyPyramid. United States Department of Agriculture, 12 May 2010. Web. 12 May 2010. <http://www.m ypyramid.gov/tips_ resources/vegetarian_diets.html>. 5. "Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Iron ." Office of Dietary Supplements . National Institutes of Health, n.d. Web. 08 May 2010. <http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/iron. asp>.