- Surrey Research Insight Open Access

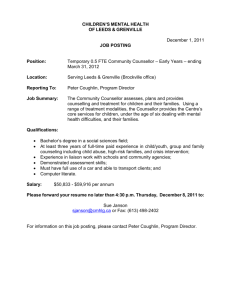

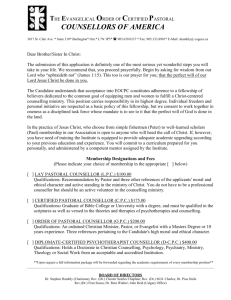

advertisement