document

advertisement

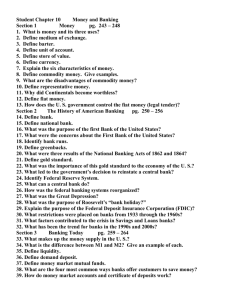

Burke 1 Sean Burke Dr. Kara McLuckie FYS 3 April 2013 Banking Regulation in the Great Depression: Harmful or Helpful? Bank failures during the Great Depression were frighteningly common. In fact, there were over 9,000 failures between 1929 and 1933 (Geewax). It is widely accepted that these failures were caused by agricultural hardships, but the idea that banking regulations may have played a key role has largely been overlooked. In the time of the Great Depression, there were two types of banks: state banks and national banks. The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 created this separation of state and national banks, which is what caused there to be a difference in regulatory policy between states and the national banks. Each state was able to implement its own regulations for state banks which, in some cases, led to more bank failures. Most of these bank failures came from one of just a handful of causes: over-competition, inefficiency, excessive risk, and lack of diversification of loans. Due to differing regulations between statechartered banks and nationally-chartered banks on branch banking and deposit insurance, bank failure rates from 1929 until 1933 varied widely by region and exasperated the Great Depression in the hardest hit areas. Branch Banking Regulation Branch banking was distrusted in the United States leading up to the Great Depression. In 1927, the McFadden Act went into effect which prohibited interstate branch banking in the United States. This forced states to decide whether or not to allow branch banking within their borders. Most states did not adopt deposit insurance for one main reason: lobbying. Unit banks Burke 2 lobbied state governments to not allow branch banking because that would have created more competition for them (Mitchener 6). Also, financial service providers (e.g. insurance companies) did not want large branch banks to impede on their profits so they too lobbied state governments (Mtichener 7). Clearly, both groups were successful in convincing legislators that unit banking was the way to go; only fifteen states relaxed restrictions on branch banking during the 1920s (Calomiris 543). States that allowed branch banking fared better than states that did not for a myriad of reasons that would not have been readily apparent in the midst of the Depression. In states that did not allow branch banking there were massive startup costs for new banks which reduced the competition for unit banks, banks that have no branches (Calomiris 544). This lack of competition had profound effects on the banking market; unit banks were able to operate inefficiently because they knew that few other banks would have to capital to enter the market. There was no incentive for unit banks to find ways to operate more efficiently and this caused them to be very unstable when people began to default on their loans. Unit banks had many other flaws too; since they only had one location, they were unable to diversify their loan risk (Calomiris 544). Without the ability to build a large portfolio, even a few loan defaults could be devastating to a unit bank. Unit banking also “inhibited financial integration across regions, which resulted in large differences in interest rates between the East and the West, and high seasonal volatility in liquidity risk” (Calomiris 545). Essentially, banks in agricultural areas were extremely vulnerable to failure if crop seasons were poor because the majority of their loans were to farmers. This explains the extremely high failure rates that plagued the Midwest. Lastly, unit banks were unable coordinate efforts to mediate the effects of bank runs, which occurred when depositors thought a bank was going to fail and withdrew their money causing a bank to Burke 3 fail (Calomiris 545). If branching were allowed, branch banks could have pooled their resources to assure depositors that their money would be safe, ending bank runs. Overall, unit banks were detrimental to the banking system; in counties in states that prohibited branching, bank failure rates were nearly 8% higher than in counties in states that allowed branching (Mitchener 21). Clearly, the preservation of unit banking was not in a state’s best interests. Branching had the ability to stabilize banking in states where it was allowed. Branch banking lowered the operating costs of banks and enabled branches to achieve economies of scale (Regulation, Market Structure 34). This means that the marginal cost of creating another branch reduced each time a bank created a new one, which led to lower costs and a greater ability to withstand loan defaults. According to economic theory, the economies of scale created by branch banking would inevitably lead to the market becoming an oligopoly, which is where there are a few firms that hold most of the market share. This helped to ensure that only the most efficient and stable banks would enter and succeed in the market. Branch banking was becoming more common until states began to implement deposit insurance. Deposit Insurance Regulation Deposit insurance first became prevalent in the United States as a reaction to the Panic of 1907 when 8 states adopted it (Regulation and Bank Failures 811). In just the first year Kansas offered deposit insurance, 48.9% of banks joined the voluntary system (Regulation and Bank Failure 812). Many of these states began allowing deposit insurance as a way of trying to save unit banks from the onslaught of branches (Calomiris 547). A regulation passed to save an inefficient and dying form of banking is bound to end poorly; and it did. Calomiris says, “Eight states had enacted deposit insurance systems for their state-chartered banks. All of these systems ended disastrously during the agricultural distress of the 1920s” (547). Burke 4 In states that allowed it, deposit insurance devastated the banking system. Bank failure rates in states that had deposit insurance were 1.86 failures per 100 banks higher than in states that prohibited it (Alston, Grove, and Wheelock 428). This is a significant amount considering the hardest hit state had a failure rate of 12 failures per 100 banks. This is partly due to the fact that deposit insurance led to the proliferation of banks that were not diversified and failed easily in states permitting it (Regulation, Market Structure 32). Because banks did not have to worry about what would happen if they failed, they had no reason to build a diverse portfolio of loans that would be resistant to loan defaults. This led banks to be riskier with their investments because depositors would not withdraw their funds if they thought a bank may fail. This caused banks with insurance to take more risks by approving less desirable loans to increase profits (Alston, Grove, and Wheelock 418). Possibly the most harmful effect of deposit insurance was that it led to the proliferation of banks which were not diversified and failed easily in states permitting insurance (Regulation, Market Structure 32). This was due to the fact that deposit insurance reduced the risk of starting a bank so many new banks entered the industry, many of which were poorly managed. State-chartered banks with deposit insurance had great difficulties when disaster struck because they had very risky portfolios. Kansas provides an interesting case-study for deposit insurance short comings. Banks that were insured in Kansas’ voluntary deposit insurance system had the largest profits during the agricultural boom, but fell the most afterwards (Regulation and Bank Failure 811). Insured banks had little incentive to be safe with their loans because there was little penalty for not maintaining adequate capital and even then, supervision of these regulations was lacking at best. Banks only had to pay .05% annual premiums on their insured deposits minus the amount of capital they held. Clearly, there was some incentive to maintain Burke 5 capital, but making risky loans could result in much more profit than preserving capital. In fact, insured banks had “significantly lower capital-to-asset ratios than noninsured banks and seem to have taken greater risks as they approached failure” (Regulation and Bank Failure 813). The result of this was that state-chartered banks with deposit insurance had a failure rate of 4.6%, whereas non-insured state banks had a failure rate of 2.3% and national banks had a failure rate of 0.8% (Regulation and Bank Failure 813). Kansas provides a microcosm for the entire deposit insurance system that was such an utter failure in the Great Depression era. Regulations during the Great Depression that were meant mainly to save the crumbling unit banking system proved fatal to many banks. Restrictions on branch banking were the result of a successful lobbying effort by unit banks and insurance companies alike. These restrictions were meant to increase the profits of the unit banks but, during the Depression, had the unfortunate effect of leading to the demise of many unit banks due to their inability to build large, diverse portfolios and to coordinate effort to counteract bank runs. Deposit insurance was a last-ditch effort by unit banks to combat the rise of branch banking. Again, this initiative failed miserably as banks that had opted to enter the deposit insurance system failed at a much higher rate than banks that were not insured. Insured banks were much riskier than their counterparts and often held significantly less capital which led to a great increase in profit during the agricultural boom, but a massive decline during the Depression that caused many insured banks to becoming even riskier and fail more often. Burke 6 Works Cited Alston, Lee J., Wayne A. Grove, and David C. Wheelock. "Why Do Banks Fail? Evidence from the 1920s." Explorations in Economic History 31.4 (1994): 409-31. Print. The authors of this article argue that rural communities were hardest hit by bank failures. They say that 80% of all bank failures were in rural areas. At the time, 2/3 of all banks in the country were in rural communities of 2,500 people or less. The number of banks in those communities fell by 27% as compared to only .4% in cities of 50,000 or more people. The authors also argue that there was no real agricultural depression in the late 1920s; they believe that the early 1920s were too good to farmers and when things went back to normal, farmers had borrowed too much to stay afloat. They go on to say that the Federal Farm Loan Act created over-competition in the banking industry which caused banks to lower their standards in order to attract borrowers. Deposit insurance caused the failure rate to be 1.86 banks per 100 higher. This article is relevant to my research because it discusses in great detail the statistics of bank failure. These stats are important for my paper because it needs numerical evidence to back up the claims. It also corroborates what other articles said. Explorations in Economic History is a peer-reviewed journal that discusses the quantitative aspects of economics in history and is definitely credible. Calomiris, Charles W. "The Political Lessons of Depression-era Banking Reform." Oxford Review of Economic Policy 26.3 (2010): 540-60. Print. In this article, Calomiris argues that regulations on branch banking had a detrimental impact on the Great Depression. He says that, by not allowing branch banking, states were creating large barriers to entry into the banking industry which allowed unit banks to operate inefficiently and have no Burke 7 incentive to increase efficiency. He also argues that restrictions on branch banking prevented banks from diversifying their funds because they had no way to expand business. Restrictions also created regulations that differed widely by region which led to differing rates of failure during the Depression. Lastly, there was no way for unit banks to realistically coordinate their efforts to lessen the effects of the Depression because branch banking was outlawed in most states. This particular article is relevant to my research because it provides many reasons why regulation of banks worsened the effects of the Depression. The rationale presented will be helpful when I present my argument about how regulation of banks affected the Depression. The Oxford Review of Economic History is a peer-reviewed journal that focuses on current issues in economics which contributes to its credibility. Calomiris is also a professor at Columbia which shows his professionalism. Geewax, Marilyn. "Did the Great Recession Bring Back the 1930s?" NPR. National Public Radio, 11 July 2012. Web. 18 Mar. 2013. <http://www.npr.org/2012/07/11/155991507/did-the-great-recession-bring-back-the1930s>. This article presented some very helpful background information on the Great Depression as a whole. It talks about how the Great Depression was much worse than the recent recession facing the United States. The Great Depression was longer, caused more unemployment, dropped prices, caused more bank failures, and dropped the Dow Jones a whopping 89%. The most pertinent information to my research was the amount of bank failures which were over 9,000 in the Great Depression and "only" 443 in the Great Recession. This resource is helpful to my research because it gives a launching point for finding Burke 8 other information. I took the information I found here and tried to dig more in depth with other articles to complement this one. This source is extremely credible as NPR is widely regarded as a mostly unbiased source of information with a large base of readers and listeners. Geewax is a senior editor, assigning and editing business radio stories at NPR as well as the national economics correspondent for the web site. "Managing the Crisis: The FDIC and RTC Experience." Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. N.p., 5 Jan. 2005. Web. 20 Feb. 2013. <http://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/Chron/pre-fdic/>. This article discusses the amount of bank failures each year and how much money was lost by these failures. The year with the most failures was 1933 with 4,000 failures followed by 1931, 1932, and 1930 respectively (all with more than 1,000 failures). These years were also the worst for the amount of money that depositors never got back with each year over $100,000. Lastly, these years saw the most losses to depositors as % of deposits in all banks with between .57% and 2.15% of total deposits lost. The numbers presented will aid me in supporting my thesis as well as exemplifying the effects of the Great Depression bank failures. The FDIC is credible because it is a government organization that is deeply involved in the banking affairs of the country. Mitchener, Kris James. "Banking Supervision, Regulation, Instability during the Great Depression." National Bureau of Economic Research. N.p., May 2004. Web. 20 Feb. 2013. <http://www.nber.org/papers/w10475.pdf?new_window=1>. Mitchener presents the idea that differences in state and federal regulation arose from the National Banking Acts of the 1860s. He say that this led to different regulatory standards with the national banks being much more tightly regulated. State regulatory decisions were heavily Burke 9 influenced by private interest groups which could easily lobby legislators (examples of private interest groups are given). Also, capital requirements were effective at reducing banks failures when increased. The main point in the article is that differences in state and national regulation were devastating to banks in the Great Depression. This will help with my paper because it uncovered the source of the differing federal and state regulation (National Banking Acts of the 1860s) which explains much of my other research. The information about private interest groups is also very interesting and will contribute to my discussion on why regulation differed. The National Bureau of Economic Research is credible because it is a private, non-profit research organization with many Nobel prize winners as associates. Mitchener is also the Robert and Susan Finocchio Professor of Economics at the Leavey School of Business, Santa Clara University. Wheelock, David C. "The Federal Response to Home Mortgage Distress: Lessons from the Great Depression." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 90.3 (2008): 133-48. Print. The author of this article argues that branch banking is more efficient form of insurance against bank failures than deposit insurance is. He says that much of the problem with bank failures stem from the false sense of security that occurred during the agricultural boom after World War I. During the boom, land values rose and more valuable mortgages were taken out. This caused debt to skyrocket in agricultural communities. As farmers defaulted on their loans, many banks failed. During the Depression, 119 statecharter banks failed and only six nationally-chartered banks failed and this was mainly due to regulatory differences. The reason many states adopted deposit insurance was the Panic of 1907. Deposit insurance caused banks to have a greater boom in the good years, Burke 10 but have a much sharper decline in the Depression. Insured banks had double the failure rates of non-insured ones and many depositors who bought into the insurance system did not get their money back. National banks had a better reputation than state banks which may have caused state banks to fail quicker and more often. This paper is pertinent to my essay because it uses case studies to identify the true causes of bank failures. It also does a very good job in comparing state and national regulation which seems to be a major factor in whether or not a bank failed. the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis Review is credible because it is associated with the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis which is one of 12 regional reserve banks that make up the U.S. central bank. David C. Wheelock is Vice President and Deputy Director of the Research Division of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. - - -. "Regulation and Bank Failures: New Evidence from the Agricultural Collapse of the 1920s." Journal of Economic History 52.4 (1992): 806-25. Print. This article mainly talks about what regulations were detrimental during the Great Depression. Deposit insurance was harmful because it increased the amount of risks a bank was willing to take. This was due to the fact that banks did not have to pay increasing premiums with increasing risk which provided no deterrent to risk taking activity. Also, the agricultural boom of the early 1920s led to a false sense of security for many farmers which increased their borrowing and caused them to default on their loans when hardship struck. Wheelock argues that the Panic of 1907 compelled many states to adopt deposit insurance which would seem helpful for many years, but eventually contributed to collapse. Insured banks failed at nearly twice the rate of uninsured ones and many depositors did not get their full deposits back. Burke 11 My research will benefit from this information because it informed me that deposit insurance stemmed from the Panic of 1907 which can contribute to my background information section. It also has relevant information about the reasons why rural communities were hit so hard by the Depression. The Journal of Economic History is peer-reviewed journal that focuses on quantitative economic history which leads to its credibility. - - -. "Regulation, Market Structure, and the Bank Failures of the Great Depression." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 77.2 (1995): 27-38. Print. Wheelock argues that bank failures were particularly bad in the Midwest during the Great Depression. He goes on to say that this was mainly due to agricultural distress, but that many economic historians have overlooked the regulatory aspects of failure. Much of the failure, he argues, comes from the different regulatory policies between state-chartered banks and nationally-chartered banks. State banks were smaller and less regulated. Many states also did not allow branching which would have diversified banks and kept them from failing so easily. He also says that state-level deposit insurance contributed to bank failures because insurance allowed banks to take much greater risks in their loans, etc, and also because it allowed for too much competition leading to artificially low interest rates. This is relevant to my paper because it gives lots of overview on the cause of bank failures. It gives me an understanding of what the government did not do that could have stopped bank failure. This helps to understand the difference in bank failures by state.