Eating

Disorders

Psychological

and Clinical Perspectives: Assessment,

diagnosis, treatment and explanations.

A critical look- what has been ignored?

Devinder Rana BSc (Hons) Psychology LM40507 Psychopathology and Abnormal Psychology

Aims

By the end of the session you will be able to

do the following:

Describe how the DSM-IV-TR defines and

distinguishes different eating disorders.

Describe and compare how the biological,

psychological and sociocultural perspectives

explain the aetiology of eating disorders.

Analyse the different treatments and

perspectives and their legal and ethical

implications.

Eating Disorders

1. Anorexia Nervosa

2. Bulimia Nervosa

3. Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified

(EDNOS) Binge-eating disorder (proposed

diagnosis requiring further study).

Anorexia Nervosa

Criteria DSM-IV-TR

Refusal to maintain a body weight that is normal

for the person’s age and height (i.e., a reduction

of body weight to about 85% of what would be

normally expected).

Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat,

even though underweight.

Distorted perception of body shape and size.

Absence of at least three consecutive menstrual

cycles.

Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (2000). American

Psychiatric Association.

In-text citation: APA (2000)

Sub-types (APA, 2000).

2 sub-types –

how they

maintain weight

Binge/eating,

purging type

Out of control eating

Food amounts far greater then

average consumption

Followed by efforts to purge

Restrictive Type

Calorie in-take controlled

Limit food in-take

Avoid eating in the presence of other people

Eat slowly, cut and play with food

(Beaumont, 2002)

In Context DSM-VI-TR (2000)

Criteria

A 5’11 adult weighing

11 stone (70 kilos)

falls into the OK

category.

A deviation of 15%

results in the

individual now

weighing just over 9

stone and is

subsequently classed

as anorexic.

Epidemiology

80-90% of suffers are female with typical

age onset between 14-18 years old (Pike,

1998).

Weight control remains a long-term issue.

Links with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Occur in young children

Occur in boys

Ballet dancers (Gelsey Kirkland)

and gymnasts (Christy Henrich)

Characteristics of Anorexia

Anorexic’s develop eating habits typical of

bulimia nervosa (e.g. maintenance of ‘normal’

weight through abnormal eating habits).

Socio-economic and academic achievement

link.

Pre-occupation with food- thoughts of eating,

preparation of food or watching others eat.

High ‘calorie consumption’ behaviours e.g. gym,

running or swimming.

Young, European American Women .

Distorted body image

Over estimation

of body

proportion and

distorted body

image (Gupta &

Johnson, 2000).

Link with

depression,

anxiety and OCD.

Effects of Anorexia

Amenorrhea (lack of menstruation).

Immune infections

High/low blood pressure

Cracked Skin

Brittle hair and bones

Cardiotoxicity (heart damage)

Consequences

Mortality rate is 12x higher than the

mortality rate for females aged 15 to 24 in

the general population (Sullivan et al

1995).

Death results from:

Physiological consequences from starvation

Intentional suicidal behaviour

Historical Account and Definition

Anorexic nervosa means:

“ lack of appetite induced by

nervousness”.

(Butcher et al, 2007).

Lack of appetite is not the real problem.

“Self-starvation, resulting in a minimal

weight for one's age and height or

dangerously unhealthy weight”.

Hudson et al (2006).

Greek

An: without

Orexis: a desire for

“ without desire for food”

Nevid et al (2008).

Central to anorexia nervosa

Fear of gaining weight

or becoming fat

Refusal to maintain

even a minimal low

body weight.

Historical Accounts

Accounts in early religious literature

(Vandereycken, 2002).

First medical account published in 1689 Richard

Morton.

18 year old girl and 16 year old boy- described

as having a:

“nervous consumption that

caused wasting of body tissue”.

1873 Sir William Gull in London & Charles

Lasegue in Paris independently describe the

clinical syndrome and receive its current name.

Gull (1888)

Described a 14 year old girl:

“Without apparent cause, to evidence a

repugnance to food, and soon afterwards

declined to take whatever, except half a

cup of tea or coffee”.

Problems with the diagnostic tool:

DSM-IV-TR

Women who continue to menstruate but

meet all the other diagnostic criteria for

anorexia nervosa are just as ill as those

who have amenorrhea (Cachelin & Maher,

1998; Garfinkel, 2002).

For men, the equivalent of the

menstruation criterion is diminished sexual

appetite and lowered testosterone levels

(Beaumont, 2002).

Bulimia Nervosa

Criteria DSM-IV-TR

Recurrent episodes of binge eating.

binges in a fixed period of time, food far greater than normal circumstances.

Lack of control and unable to stop.

Recurrent and inappropriate efforts to

compensate for the effects of binge eating.

self induced vomiting

laxatives

excessive exercise

thyroid medication

Self-evaluation is excessively influenced by

weight and body shape.

Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (2000). American

Characteristics

Food is eaten rapidly, secretively, without pleasure in

binges where in excess of 5000 calories can be

consumed (2x the recommended daily male intake).

Bulimics demonstrate a fear of weight gain and consider

themselves to be heavier than they actually are

(McKenzie et al 1993)

Approximately 80-90% of individuals will vomit following

a period of binging, one third adopt laxative use and

others constantly exercise (Anderson et al, 2001).

Long-term problems include digestive issues,

dehydration, damage to stomach lining and damage to

the teeth.

Fairburn & Beglin (1994) estimate prevalence between

0.5-1%.

Anorexia Vs. Bulimia

Anorexia

Bulimia

Weight loss not driven by

desire to appear feminine.

High self-control

Social concept of femininity

drives behaviour

Impulsive and emotional

instability

Body weight significantly

(>15%) below age/height

Less likely to have been

overweight

Underweight (severe)

Weight fluctuation (remains

relatively close to norms)

More likely to have been

overweight

Normal weight (slightly

overweight)

Less likely to abuse

drugs/alcohol

More likely to abuse

drugs/alcohol

Bulimia and Purging anorexia

nervosa

Meets the criteria for binging/purging, also

meets the criteria for anorexia nervosa,

anorexia nervosa will be diagnosed.

Common anxiety with fear of being fat.

2 types

Bulimia

Purging (80%)

Non-purging

Vomiting

Fast/exercise

Use of laxatives

Explanations

Complex Interaction

Psychological

Biological

Socio-cultural

family

Individual

Biological Factors

Genetics

Genetics

Runs in families (Bulik & Tozzi, 2004)

Risk of anorexia nervosa for relatives of people

with anorexia nervosa was 11.4x more greater.

Bulimia 3.7X higher, than relatives with healthy

controls. (Strober et al, 2000).

Relatives of patients with eating disorders are

more likely to suffer from other problems,

especially mood disorders (Mangweth et al

2003).

However, eating disorders are not densely

clustered as are mood disorders and

schizophrenia.

Twin studies

Anorexia nervosa and

bulimia nervosa are

hereditable disorders

(Bulik & Tozzi, 2004;

Fairburn & Harrison,

2003).

Genes

Chromosome 1 linked to

the susceptibility to the

restrictive type of

anorexia (Grice et al,

2002).

Bulimia (purging) linked

to chromosome 10

(Bulik et al, 2003).

Eating disorders linked to

chromosomes involved

Genes responsible for

serotonin: low serotonin

level (Kaye et al., 2005)

Brain: Hypothalamus and GLP-1

Regulates bodily functions

Lateral hypothalamus: produces

hunger when activated

Ventromedial Hypothalamus:

reduce hunger when activated

Each part electrically stimulated in

animals they decrease/increase

eating behaviour (Duggan &

Booth, 1986)

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)

natural appetite suppressant.

Inject rats they will not eat even

after a 24hr fast

Block GLP-1 in the hypothalamusdouble food intake (Turton et al.,

1996).

Weight Set Point Theory

LH, VMH, GLP-1, work together

comprise a weight thermostat

Weight set point theory (WSP)

(Hallschmid et al., 2004).

Genetic inheritance and early eating

patterns determine WSP.

Weight falls below the WSP, hunger

increases and metabolic rate

decrease.

Diet and fall below WSP, hypothalamic

activity produces a preoccupation with

food and desire to binge.

Trigger bodily changes- harder to lose

weight however little is eaten (Spalter

et al., 1993)

Restricting-type anorexia: shut down

their inner thermostat and control their

eating completely.

Binge-purge pattern: battle spirals

(Pinel et al., 2000)

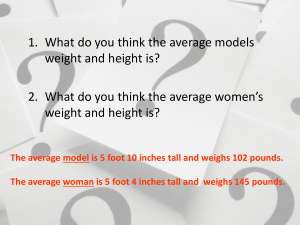

The average American

woman is 5’4” and 140

pounds.

The average American

model is 5’11” and 117

pounds.

Societal

Pressures

Current Western standards of female attractiveness have contributed

to increases in eating disorders (Jambor, 2001).

Decline Miss America Pageant, average decline of 0.28 pound per

year (Garner et al., 1980).

Fashion models, actors, dancers, certain athletes: more prone to

eating disorders (Couturier & Lock, 2006).

20% of gymnast surveyed had an eating disorder (Johnson, 1995).

White upper socioeconomic expressed more concerns about thinness

(Mrgo, 985)

Recent years increased in all classes and minority groups (Germer,

2005).

Double standard has made women more inclined to diet and more

prone (Cole & Daniel, 2005)

Cruel jokes targeted as obesity are standard in the media (Gilbert et

al., 2005)

Deep rooted (Grilo, 2006)

Parents more likely to rate a picture of a chubby child as less friendly,

energetic, intelligent and desirable.

61% of secondary school girls are dieting (Hill, 2006)

Battle of Brittan's

Timeline

1639 - The Three Graces; Pieter Pauwel Rubens

1887 - Pierre Auguste Renoir, The Bathers

1920 - Thin, short haired flapper

1950 - Monroe (Size 14/16)

1960 - Twiggy Lawson (Aka the beginning of the end.) This was the first

time in history that an under weight woman became the standard for the

ideal body image.

1988 - Cosmopolitan

2002 - Harper’s Bazaar

Modern day Fashion Model

Family Environment

Important role in the development of eating

disorders (Reich, 2005)

½ families: emphasise thinness, physical

appearance and dieting.

Mothers diet frequently and be perfectionist

(Woodside et al., 2002).

Abnormal interactions and communication (Reich,

2005)

Family systems theory: dysfunctional family,

person with eating disorder is representative of a

larger problem (Rowa et al., 2001)

Enmeshed family pattern (Minuchin et al., 1978):

over involved with in each other’s affairs and over

concerned with details of each other’s lives.

Teenagers push for independence which threaten

the harmony of the family.

Family may subtly force the child to take on a sick

role- develop eating disorder or other illness.

Enables the family to maintain its appearance of

harmony.

Some case studies support this view (Wilson et

al., 2003)

Systematic research fails to support this link .

Ego Deficiencies and Cognitive

Disturbances

Bruch built on psychodynamic and cognitive notions.

Disturbed mother-child interactions lead to serious ego deficiencies

in the child (poor sense of control and independence) serve

cognitive disturbances (Bruch, 2001).

Effective parents: attend to their child’s biological and emotional

needs

Ineffective parents: fail to attend to needs, misinterpreting i.e., being

hungry rather than seeing the actual condition- grow up confused.

Not being control of their behaviour, not rely on internal signs, not

self-reliant instead during adolescence when looking for

independence seek control with weight and body image.

Pearlman (2005) eating disorder parents define children needs

rather than the child.

Bruch (1973) interviewed 51 mothers of a child with an eating

disorder, many recalled how they never allowed the child to feel

hungry and anticipated their child’s needs.

Perceive internal cues inaccurately (Bydlowski et al., 2005)

Anxious or upset- think they are hungry so eat

Worry how others view them, seek approval, be conforming and feel

lack of control over their lives (Button & Warren, 2001).

When do people seek junk food? When they feel bad.

Lyman (1982)

boredom

depression

anxiety

nurition

junk food

love

happiness

self-confidence

0

20

40

60

80

100

Mood Disorders

Eating disorders, especially bulimia nervosa,

experience symptoms of depression (Perinea et al,

2005)

Eating disorder also qualify for a clinical diagnosis of

major depressive disorder (Duncan et al., 2005)

Close relatives of people with eating disorders seem to

have a higher rate of mood disorders than do close

relatives of people without such disorders (Moorhead

et al., 2003).

Eating disorders, especially bulimia nervosa have low

activity of serotonin, similar to serotonin abnormalities

found in depressed people.

People with eating disorders are helped by some of

the same antidepressant drugs that reduce

depression.

Treatments for Anorexia

Nervosa

How is proper weight and normal

eating restored?

Past in hospitals, today in outpatient settings (Vitousek &

Gray, 2006)

Life-threatening cases: force tube and intravenous

feedings on a patient who refuses to eat (Tyre, 2005)

Can result in distrust in the patient (Robb et al., 2002).

Weight restoration approaches: clinicians use rewards

whenever patients eat properly or gain weight (Tacon &

Caldera, 2001)

– Combination of supportive nursing care, nutritional counselling &

high calorie diet (no more than 2,500 calories a day). Herzog, et

al., 2004).

– Help them to recognise that the weight gain is under control and

will not lead to obesity..

– Gain the necessary weight in 8-12 weeks.

How

are

lasting

changes

achieved

Overcome their underlying

psychological problems in order to

achieve lasting improvement

Therapy and education: individual,

group and family approaches

(Hechler et al., 2005).

Recognise need for independence

and teach them more appropriate

ways to exercise control (Dare &

Crowther, 1995).

Trust their internal sensations and

feelings (Kaplan & Garfinkel,

1999)

Correcting disturbed cognitions:

change attitudes about eating and

weight (McFarlane et al., 2005).

Identify, challenge and change

maladaptive assumptions (Lask et

al., 2000)

Changing family interactions: meet

with the family, point out

troublesome family patterns,

separate feelings and needs from

those of other family members

Aftermath of Anorexia Nervosa

Use of combined approaches has improved the outlook but the road to

recovery is difficult (Fairburn, 2005)

Positive

Weight is often restored once treatment begins (McDermott & Jaffa, 2005)

83% improvement, several years later, 33% fully recovered and 50%

partially improved (Herzog et al., 1999)

Menstruate again (Fombonne, 1995)

Death rates are decreasing (Neumarker, 1997).

Negative

20% remain seriously troubled for years (Haliburn, 2005)

When recovery occurs it is not always permanent

1/3 triggered again by new stresses (Fennig et al., 2002)

½ continue to experience emotional problems- depression, social anxiety,

obsessive which are common when reaching normal weight (Steinhausen,

2002)

Treatment Bulimia Nervosa

Treatments

Eating disorder clinics

Eliminate binge-purge patterns and establish god eating patterns,

Education as much as therapy (Davis et al 1997)

Individual insight therapy: cognitive-recognise and change

maladaptive attitudes (Cooper, 2006)

Not respond then use interpersonal psychotherapy- improve

interpersonal functioning.

Psychodynamic therapy- limited support.

Behavioural therapy: supplement with cognitive

Dairies- note sensations of fullness etc

Exposure and response prevention

Anti-depressant medication: Prozac help 40%

Group therapy: self-help groups- helpful to 75% when combined with

individual sight therapy

Aftermath

Treated successfully, relapse is a common

problem triggered by new life stresses.

1/3 treated relapse 6months later

(Olmsted et al., 1994)

Former patients less depressed then time

of diagnosis (Halmi, 1995)

Depends on history, length and frequency

of vomiting.

Karen Carpenter: 1970’s

Reading Seminar

Should individuals with Anorexia

Nervosa Have the Right to Refuse LifeSustaining Treatment?

Yes: Heather Draper from “Anorexia Nervosa

and Respecting a Refusal of Life-Prolonging

Therapy: A Limited Justification”, Bioethics (April

1, 2000)

No: J.L. Werth, Jr., Kimberly S. Wright, Rita J.

Archambault, and Rebekah J. Bardash, from

“When Does the ‘Duty to Protect’ Apply with a

Client Who Has Anorexia Nervosa?” The

Counselling Psychologist (July, 2003).

Petrie, T., Greenleaf, C., Reel, J., & Carter, J. (2008,

October). Prevalence of eating disorders and disordered

eating behaviors among male collegiate athletes.

Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 9(4), 267-277.

Retrieved January 22, 2009, doi:10.1037/a0013178

Tibon, S., & Rothschild, L. (2009, January). Dissociative

states in eating disorders: An empirical Rorschach study.

Psychoanalytic Psychology, 26(1), 69-82. Retrieved

January 22, 2009, doi:10.1037/a0014675

Hepworth, J., & Griffin, C. (1995). Conflicting opinions?

'Anorexia nervosa,' medicine and feminism. Feminism

and discourse: Psychological perspectives (pp. 68-85).

Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc.

Retrieved January 22, 2009, from PsycINFO database.

Wu, K. (2008, December). Eating

disorders and obsessive-compulsive

disorder: A dimensional approach to

purported relations. Journal of Anxiety

Disorders, 22(8), 1412-1420. Retrieved

January 22, 2009,

doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.02.003

Reading

Nevid, J.S., Rathus, S.A., & Greene, B.

(2008). Abnormal Psychology In A

Changing World. (7th ed.). Pearson

Prentice Hall: London. Chapter 10, pp.

330-357.

End