Encomienda Reading

advertisement

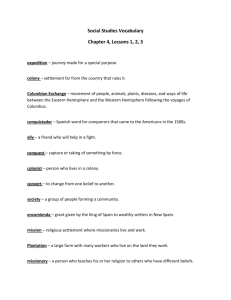

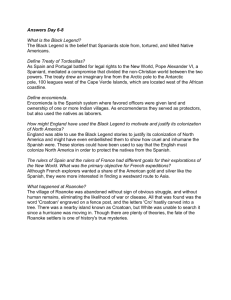

West Morris Central High School Department of History and Social Sciences Encomienda From: Encyclopedia of World History: The First Global Age, 1450 to 1750, vol. 3. Encomienda ranked among the most important institutions of early colonial Spanish America. Described as a kind of transitional device between the violence of conquest and the formation of stable settler societies, encomienda has been the topic of enormous research and debate among scholars. Rooted in the verb encomender ("to entrust", "to commend"), an encomienda was a grant of Indian labor by the Crown to a specific individual. Holders of such grants, called encomenderos, were said to hold Indians in encomienda or "in trust." The institution and practice of encomienda originated during the Spanish Christian reconquest of Iberia from the Moors (718–1492 C.E.), creating an institutional template that was quickly transferred to the New World after 1492. Unlike its Iberian predecessor, encomienda in the Americas did not include land grants, except occasionally in marginal areas. Instead, it was primarily a mechanism of labor control that also permitted the Crown to maintain the legal fiction that Indians held in encomienda were technically free, were not chattel, and could not be bought or sold. It also served as an effective way to reward conquistadores and others in service to the Crown, including priests and bureaucrats. The term encomienda was often used interchangeably with repartimiento ("distribution" or "allotment") during the early years of conquest and colonization, though the two were legally distinct. The later practice of compelling subject Indian communities to purchase Spanish goods, common in the 17th and 18th centuries, was also called repartimiento. Later forced-sale repartimiento had little relation to the institution of encomienda. The first substantial effort to codify encomienda in the New World were the Laws of Burgos (1512–13), which required encomenderos to "civilize," "Christianize," protect, and treat humanely Indians held in encomienda. A vast corpus of subsequent laws, proclamations, and edicts further refined and limited the institution. The practical effect of these laws was minimal. In practice encomienda was akin to slavery, especially during the early years of the conquests. Abundant evidence exists of the abuses and mistreatment inflicted upon encomienda Indians, who were bought and sold, worked to death, and in other ways treated for all practical purposes as slaves. These abundant abuses prompted some Spaniards to condemn the institution as unchristian, most prominently the priest Bartolomé de Las Casas, beginning in 1514. In response to this simmering debate, in 1520 Holy Roman Emperor Charles V decreed that the institution of encomienda was to be abolished. In the Americas the decree had little practical effect, as most encomenderos and officials ignored it. The Crown, concerned that encomenderos not become a permanent aristocracy, continued its efforts to impose strict limits on the institution, culminating in the so-called New Laws of 1542–43, which from the perspective of encomenderos were far more draconian than the Laws of Burgos issued 30 years earlier. The major features of the New Laws included provisions preventing the inheritance of encomiendas; the forbidding of new grants, requiring royal officers and ecclesiastics to give up their encomiendas; and prohibitions against Indian enslavement for whatever reason. The New Laws provoked an outcry across the colonies, especially in Peru, where factions of colonists rose in rebellion against them. In 1545–46, three years after they were issued, the New Laws were repealed as unenforceable. Encomienda nevertheless died a slow death over the next half-century. The principal cause for its decline was not royal decree but Indian depopulation. Grants of Indian labor became moot when there were so few Indians left to grant. Encomienda lasted less than a century in most areas, enduring into the late colonial period only in peripheral regions such as Yucatán. The transition from encomienda to hacienda (private landownership) was neither direct nor clearcut, and comprises another major arena of scholarly research and debate.