Language Development

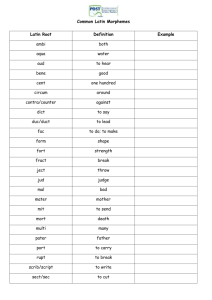

advertisement

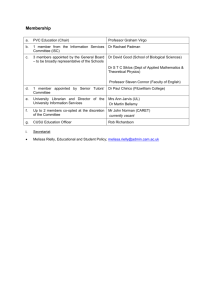

Language Development 004797495 12/2/2010 California State University, Chico Melissa J. Norton Melissa Norton 004797495 Language Development Language is the principal mode of human communication and made up of several components (Schwartz, Fall 2010, PSYC 353). It allows individuals to translate mental activities into conscious thoughts and memories. It also allows us to express our needs and to transfer what we know about the world to subsequent generations. For the purposes of this paper, three children were observed using language in varying settings; the first child was male and 17 months of age. The second child observed was male and 34 months of age and the third child observed was a female aged 74 months. It was evident from these observations which element of language each child was utilizing relative to early language development. Dylan, 17 months, was observed after arriving at daycare in the morning. During my observation of Dylan, he demonstrated basic phonological awareness through his use of words like “no” and “shhh.” Phonology refers to the sounds of a language; babbling can be these sounds, however, babbling contains only a small subset of all the sounds found in human language (Locke, 1983; Oller, 1980; Bjorkland, 2005). Bjorkland also told us that the vocabulary of 18-24 month olds consists of only a few dozen words (2005). The words known by children aged 18-24 months are words which are important to them and can illustrate things like what happened, what belongs to whom, names of familiar people and objects and where familiar people and objects are located. Words stating nonexistence such as “all gone” and words depicting requests like “more” and “again” are also used by children in this stage (Bjorkland, 2005). When a friend approached the doll in his arms, Dylan screamed, “ahhh,” until his Melissa Norton 004797495 teacher gave him the words, “my baby,” to tell his friend about his current possession of the babydoll. Nathaniel, 34 months, was observed after arriving at daycare in the morning. Nathaniel demonstrated knowledge of syntax when he expressed himself using a negative, saying, “No shark eat me.” Syntax is the grammatical knowledge of rules for how words are combined into sentences and how sentences can be transformed to reflect an active or passive voice (Bjorkland, 2005). More sophisticated examples of negatives like, “I don’t want to do it” are associated with longer sentences in more developed children (Bjorkland, 2005). The learning of syntax has been proposed to be innate due to the fact that during the first five years of life, most children become experts in their native language (Chomsky, 1957; Bjorkland, 2005). A mental organ or language acquisition device was used by Chomsky to explain the innateness of language. More current theorists of language development state that in addition to possessing this ‘mental organ’ for language acquisition, children also have primitive knowledge at birth about the syntax of language; this is known as universal grammar (Bjorkland, 2005). Universal grammar encompasses the set of principles and parameters which guide human’s interpretation of language (Bjorkland, 2005). Having universal grammar allows children to incorporate new language with the inborn so that their theory of syntax will align with the theory that those people around them use. Nathaniel also displayed egocentricity in his communicating and language during the observation. He asked, “See my jammies?” when I said, “Good morning,” and used Melissa Norton 004797495 the statement, “I two,” after his sister had asked me how old I was. Piaget called these kinds of conversations collective monologues, meaning that Nathaniel and I were talking “with” each other, but not necessarily “to” each other (1955; Bjorkland, 2005). Maddli, 74 months, was observed arriving home after a day at school and afterschool program. During my observation, it was clear that Maddli was demonstrating knowledge of morphology. Morphological development in language is the structure of words (Bjorkland, 2005). A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning in a language; morphemes can be free or bound. Most of the morphemes children learn are word endings like –ing, –ed and adding s to form a plural from a noun. When children have learned these rules for certain words, they may then apply them to all words, even when it is not correct to do so. An example of this would be when Maddli said, “he selled a nead.” This phenomenon is called overregularization and is found in children learning to speak a variety of languages around the world (Slobin, 1970; Bjorkland, 2005). The average number of morphemes a child uses in a sentence or the MLU is a good measure of how far a child has developed linguistically (Bjorkland, 2005). From the language sample, a table showing Maddli’s MLU was derived. On average, Maddli used 7 morphemes per sentence. It was also apparent that Maddli recognized how language could be adjusted to fit different circumstances in different contexts. This knowledge is referred to as pragmatics. Conversational guidelines fall under the umbrella of pragmatics, such as knowing that messages must contain the right amount of information, be relevant and be truthful (Bjorkland, 2005). Melissa Norton 004797495 Children far surpass adults in ability to acquire both first and second languages, however, they must be exposed to language early in life in order to be able to become experts (Bjorkland, 2005). Theories like that of Chomsky’s LAD and universal grammar support this idea of a critical period for language development. An enriched environment, like that of school and quality daycare programs, paired with knowledgeable adults who use proper behavioral and guidance techniques will ensure children achieve their utmost potential in learning their native language, as well as second and third languages. Melissa Norton 004797495 References Pages 1-3 Raw Notes Pages 4-5 Language Samples Page 6 Table 1 MLU for 74-month-old Page 7 Class Notes 11/2/2010 Works Cited Bjorkland, D.F. (2005). Children’s Thinking: Developmental Function and Differences. (4th ed.) Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Schwartz, N. H. (Fall 2010). PSYC 353: Learning in the Young Child. California State University, Chico.