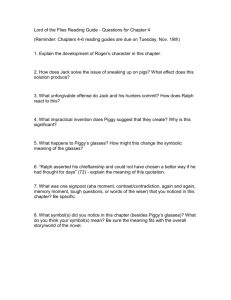

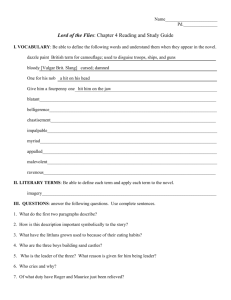

Lord Of The Flies - full text

advertisement