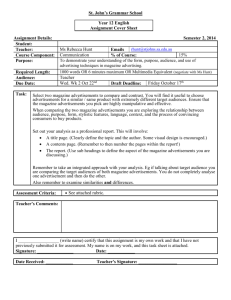

Strickland Katelyn Strickland Maharaj Writing 10 November 6 2013

advertisement

Katelyn Strickland Maharaj Writing 10 November 6 2013 Research Proposal This paper is going to discuss advertisements, and the role they play in shaping women’s views of themselves. Advertisements are potent against a woman’s self-esteem due to human nature; human beings compare themselves. “Humans are called ‘the comparing creatures’"(McLeod). A woman on a mission to bring women equality, Gloria Steinem’s “Sex, Lies, and Advertising” provides good feedback from a journalist who refused advertisements in her magazine. She describes how the women following her magazine were not interested in the “women’s” products anyway. One must take into consideration the age and education levels of women reading Steinem’s magazine. This is a good example of women who are not extremely vulnerable to the media’s grasp. Craig’s essay “Men’s Men and Women’s Women” provides an explanation of how men and women are portrayed (for or to each other). Although women are now a major part of the work force, Craig points out the portrayal of women and men in modern advertisements still follows old fashion stereotypes. He remarks on the sexual emphasis on women in advertisements. This is evidence for the question of whether ads promote stereotypes. A study done by Tiggeman and Mcgill will provide evidence of women’s body dissatisfaction being higher after viewing a thin-ideal advertisement. Tiggeman and Mcgill comment that this may not be the media’s fault, but instead the fault lies within women’s way of comparing themselves to other women. Comparison though, as addressed before, is human nature. It is foolish for advertising agencies to ignore human nature and continue to use the human psyche to get consumers to purchase their products. Monro and Huon find the same results as Tiggeman and Mcgill, that women’s appearance anxiety rises after viewing a thin-ideal advertisement. Strickland2 They note that vulnerability is a player in the game of women’s body issues related to the media portrayal of women. Bessenoff’s theory is that self-discrepancy is a key variable in the equation. Self-discrepancy involves the tendency to compare oneself to another, and (the important variable) to have self-inflicted negative consequences because of this comparison. While the other two studies provide concrete evidence and numbers, Bessenoff’s essay provides a new component I’ve not thought of previously, the negative things that go on in a woman’s psyche after constantly comparing themselves to photo shopped models. Advertisements cause women to look up to the thin-ideal, and although vulnerability of the woman is a factor, the media is still at fault. Comparison is natural for humans; therefore the media holds responsibility for increased body shame in these women. Younger women are more vulnerable to advertisement’s negative effects, and without limitation of consumption of media by parental units, young women are subject to body shame, and possibly even eating disorders. A counter argument could claim that the media is not at fault, and that the responsibility should lie in the parental units. One could even claim that it is up to the individual to not compare themselves. One could agree to this claim, but in this essay, I set out to prove that the media is unethical in its advertising, and whether parents monitor their child’s consumption of media or not, the female youth of America shouldn’t be effected as badly as they have been. Strickland3 Annotated Bibliography Bessenoff, Gayle R. "Can The Media Affect Us? Social Comparison, Self-Discrepancy, And The Thin Ideal." Psychology Of Women Quarterly 30.3 (2006): 239-251. Academic Search Complete. Web. 30 Oct. 2013. Thesis: Body-image self-discrepancy is included to the cause and effect equation between thinideal advertisements and women’s body issues. Explanation: Bessenoff has discovered, through research feedback from female undergraduates, that if a woman rates their self-discrepancy high, they are more likely to engage in social comparison. They say that “social comparison processes meditate the relationship between exposure to thin-ideal advertisements and negative self-directed effects.” Craig, Steve. Signs of Life in the USA. 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2012. 187-98. Men's Men and Women's Women. Print. Thesis: Advertisements portray men and women in different ways when advertising to either gender specifically. Explanation: There are “men’s men” in advertising, that portray strong men who use ladies as a sexual object. There are “women’s women” who portray everything a woman watching the ad would want in themselves; she tends to be beautiful, skinny, taking care of her home/husband/children. There are “men’s women” that are portrayed as objects of fantasy for the men they are advertising to. There are “women’s men” who portray a romantic and loving role toward the female in the advertisement. Craig questions a “threat to patriarchy” and claims that the American economy is in danger if patriarchy is in danger. Goodman, J. Robyn, Jon D. Morris, and John C. Sutherland. "Is Beauty A Joy Forever? Young Strickland4 Women's Emotional Responses To Varying Types Of Beautiful Advertising Models." Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 85.1 (2008): 147-168. Academic Search Complete. Web. 30 Oct. 2013. Thesis: Young women find that the less sexual an advertisement involving a woman is, the more empowered they feel. Explanation: Goodman, Morris, and Sutherland set out to discover young women’s emotional responses to advertisements displaying women. What they found is astonishing due to the amount of ads I see with naked or almost naked women. They found the young women, in this case undergraduates, find that a classic beauty, one more clothed than I am used to seeing, is more enjoyably to see, and more empowering. Monro, Fiona, and Gail Huon. "Media-Portrayed Idealized Images, Body Shame, And Appearance Anxiety." International Journal Of Eating Disorders 38.1 (2005): 85-90. Academic Search Complete. Web. 29 Oct. 2013. Thesis: Monro and Huon set out to discover the effects of “media-portrayed idealized images” on modern women. Are these images causing women to have “body shame” and “appearance anxiety?” Explanation: Monro and Huon found that after women viewed an idealized image, they rated a higher appearance anxiety. They also note that though their findings provide evidence that the media is at fault for women’s body issues, they acknowledge that the vulnerability of the particular women plays a major role in things like appearance anxiety. Steinem, Gloria. Signs of Life in the USA. 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2012. 249-69. Sex, Lies, and Advertising. Print. Strickland5 Thesis: Advertising in women’s magazines has a negative effect on women and how they view themselves; Steinem comments on the fact that her readers, who are high in intelligence, do not even use many of the “women’s” products that were previously advertised. Explanation: Steinem made a decision to keep ads out of her women’s magazines because they ads that wanted to be in there were “women’s” products that her readers didn’t even use or like. These readers, more knowledgeable than most women’s magazine readers, thought that many women reading Steinem’s magazine must use the products advertised, otherwise why would they be there? Turns out that advertisements aren’t a clear representation of what women want, but instead of what the retailer wants women, even those more informed, to want. Tiggemann, Marika, and Belinda Mcgill. "The Role Of Social Comparison In The Effect Of Magazine Advertisements On Women's Mood And Body Dissatisfaction." Journal Of Social & Clinical Psychology 23.1 (2004): 23-44. Academic Search Complete. Web. 29 Oct. 2013. Thesis: The issue of body dissatisfaction may not come directly from the media, but instead from the constant comparison women make of themselves to other, possibly more desirable, women. Explanation: Tiggemann and Mcgill claim that a lot of exposure to a “thin ideal” causes vulnerable women to compare themselves to media thin. They cite sources that claim the media, due to its pervasiveness, is at least partially at fault for the body dissatisfaction in modern western culture. The authors reason that only certain women, vulnerable and possibly heavier, are negatively affected by exposure to the “thin ideal.” They’re results show that body dissatisfaction does occur, which they conclude, proves that comparison is taking place.