Foodborne Diseases Surveillance System

advertisement

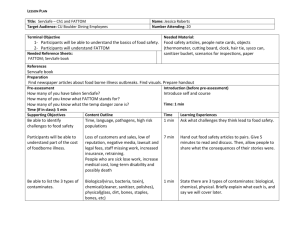

Dr. Rasha Salama M.Sc., PhD Public Health Suez Canal University Dr. Rasha is a physician (MB BCH in Medicine and Surgery- 1995) with a PhD in Public health since 2003, a master degree in Public health in 2000 from Suez Canal University, a diploma in endocrinology & diabetes from Cardiff University – UK, and Nutrition Diploma from Oxford University. She is currently working in Dubai Health Authority - joined 2011 at the Health Policy and Strategy Department, Public Health and Safety Department/ Preventive Medicine Section-as a senior specialist and worked actively to achieve the strategic goals of Dubai health sector strategy through reducing the burden of non-communicable diseases, communicable diseases and injuries in the Emirate of Dubai. She is a member of the national Public Health Law and Communicable disease Law committees in collaboration with ministry of health and a member in the Occupational Medicine Committee working on the initiative of promotion of occupational health and Safety in the Emirate of Dubai. Prior to joining DHA, She spent five years in Community Medicine Department – Hamad Medical Corporation – Qatar, as a consultant training candidates for the Community medicine Arab Board and supervising public health thesis dissertations for postgraduates, as well as publishing many papers in reputed public health journals. She was awarded Best Public Health Trainer Award for four consecutive years for Community medicine Department in HMC-Qatar (years 2006 throughout 2010) Dr. Rasha is also currently designated as a lecturer in Faculty of Medicine –Suez Canal University- Community Medicine Department, since 1995. Contact Details: Rashasalama2004@yahoo.com Foodborne illnesses are prevalent in all parts of the world, and the toll in terms of human life and suffering is enormous. Contaminated food contributes to 1.5 billion cases of diarrhea in children each year, resulting in more than three million premature deaths, (according to WHO). Those deaths and illnesses are shared by both developed and developing nations. In the United States, the CDC estimates that foodborne diseases cause approximately 76 million illnesses annually among the country’s 290 million residents, as well as 325,000 hospitalizations, and 5,000 deaths. In South East Asia, approximately one million children under five years of age die each year from diarrheal diseases after consuming contaminated food and water. Foodborne diseases create an enormous burden on the economy. Consumer costs include medical, legal, and other expenses, as well as absenteeism at work and school. Costs to national governments stem from increased medical expenses, outbreak investigations, food recalls, and loss of consumer confidence in the products. Foodborne diseases lead to increased demands on already overburdened healthcare systems in developing countries. In the US, a government estimate of seven foodborne pathogens reported a cost of between U.S. $5.6 billion to $9.4 billion in lost work and medical expenses. · In the European Union, the annual costs incurred by the health care system as a consequence of Salmonella infections alone are estimated to be around EUR €3 billion. In Australia, the cost of an estimated 11,500 daily cases of food poisoning was calculated at AU $2.6 billion annually. The symptoms of foodborne illnesses range from mild to life-threatening. While nausea and diarrhea are the most common, kidney and liver failure, brain and neural disorders, and even death can also result. For example, Listeria monocytogenes infection, which mainly affects the elderly and pregnant women, has a mortality rate of 2030 percent. Food safety challenges differ by region, due to differences in income level, diets, local conditions, and government infrastructures. Changes in animal husbandry: Modern intensive animal husbandry practices used to maximize production resulted in increased prevalence of several human pathogens, like Salmonella and Campylobacter, in flocks. Crowding of animals has been linked to the emergence of new strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Feeding practices also have come under increased scrutiny as a result of BSE. Agricultural practices have contributed to the increased risks associated with fresh fruit and vegetables, such as the use of manure, chemical fertilizers, untreated sewage, or irrigation water containing pathogens. International trade allows for the rapid transfer of microorganisms from one country to another. The increased time between processing and consumption of food leads to additional opportunities for contamination and time/temperature abuse, increasing the risk of foodborne illness. New and unfamiliar foodborne hazards can more easily reach consumers who have not developed immunities to those pathogens. Advances in processing, preservation, packaging, shipping, and storage technologies bring new forms of foods to the market, and sometimes new hazards. For example, the increased use of refrigeration to prolong shelf-life of readyto-eat foods has contributed to the emergence of Listeria monocytogenes. Persons exposed to a foodborne illness in one country can expose others to the infection in a location thousands of miles from the original source. Many trends impact the frequency and nature of foodborne illnesses. In many developed countries, a larger share of the food budget is spent on food prepared outside the home. In developing countries, there is a general rise in urban living and street food is an important component of the daily diet. As a result, outbreaks associated with food prepared outside the home are increasing in many regions. Preventing foodborne disease relies on our ability to translate knowledge of the principles of “ food safety ”to the practices of food production at each level of the food system. Foodborne disease outbreaks represent important sentinel events that signal a failure of this process. Safety of food and water is a requirement of public health. Safety refers to all those hazards which make food injurious to health. These hazards may arise at all stages of the food chain, and lack of preventive control. Specific concerns about food hazards are chemical and microbiological contaminants, biological toxins, pesticide residues, veterinary drug residues, and allergens. Public health surveillance is the foundation of communicable disease epidemiology and an essential component of a food-safety program. Effective surveillance requires the continuous collection of relevant epidemiological data, its timely analysis and interpretation of these data and the rapid dissemination of the results to all who need to know. The objectives of foodborne illness surveillance are to: ◦ determine the magnitude of the public health problem posed by foodborne diseases and monitor trends ◦ identify outbreaks of foodborne disease at an early stage in order to take timely remedial action ◦ determine to what extent food acts as a route of transmission for specific pathogens and identify high-risk foods, improper food production and handling practices ◦ determine the risk factors and behaviors for illness in vulnerable populations ◦ assess the effectiveness of programs to improve food safety ◦ provide information to enable the formulation of health policies regarding foodborne diseases (preventive strategies). In order to achieve the above objectives, various surveillance methods may be employed: Notification of human foodborne disease Laboratory surveillance of human foodborne disease Outbreak investigation of human foodborne disease Microbiological food surveillance Microbiological surveillance of food animals. Statutory notifications from medical practitioners Voluntary reporting by laboratories Informal reports from members of the public. Multiple types of surveillance systems are used related to foodborne disease. Some of them, including notifiable condition surveillance, complaints from consumers about potential illness, and reports of outbreaks, focus on the detection of specific enteric diseases likely to be transmitted by food and have been used extensively by health-related agencies for decades. More recently, new surveillance methods have emerged including: ◦ hazard surveillance, ◦ sentinel surveillance systems, and ◦ national laboratory networks for comparing pathogen subtypes Begins with an ill person who seeks medical attention. The health-care provider sends a specimen to the laboratory for the appropriate tests, and the laboratory identifies the agent responsible for the patient’s illness so the patient can be treated. Next, the laboratory or health-care provider notifies local public health officials of the illness. Once the patient’s information goes to a public health agency, the illness is no longer considered as an isolated incident but is compared with other similar reports. Combining the information in these separate reports allows investigators to identify trends and detect outbreaks. Notifiable disease surveillance is “passive”—i.e., the investigator waits for a disease report from health-care providers, laboratories, and others who are requested or required to report these diseases to the public health agency The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is a system of health surveys that collects information about health risk behaviors, preventive health practices, and health-care access primarily related to chronic disease and injury. BRFSS can be used to identify behaviors, such as food handling methods, or trends, such as changes in the number of meals eaten outside the home, that can provide information about efforts to prevent foodborne illness Factors that contribute to foodborne outbreaks (e.g., factors that lead to contamination of food with microorganisms or toxins or allow survival and growth of microorganisms in food) are used to develop control and intervention measures at food-service establishments. Routine inspections then focus on implementation of these measures. Often referred to as Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) inspections, this is the basis for hazard surveillance. Foodborne outbreak surveillance officials from health departments gather information about contributing factors in outbreaks from environmental assessments Sophisticated listing of factors based on known microbiologic characteristics of and symptoms produced by specific pathogens, toxins, or chemicals and historical associations between known causative agents and specific food vehicles. A sentinel surveillance system, is an enhanced foodborne disease surveillance system Objectives: 1. Determine the burden of foodborne illness 2. Monitor trends in the burden of specific foodborne illness over time 3. Attribute the burden of foodborne illness to specific foods and settings 4. Develop and assess interventions to reduce the burden of foodborne illness Example: FoodNet led by CDC National Molecular Subtyping Network for Foodborne Disease Surveillance (PulseNet): is a network of laboratories coordinated by CDC that allows comparison of subtypes of pathogens isolated from humans, animals, and foods. The name derives from pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), a laboratory method used to determine the molecular fingerprints of bacteria. Because foodborne outbreaks usually are caused by a single bacterial strain, investigators can identify illnesses in the subgroup of persons infected with the same strain of as a cluster of possibly related cases, to be considered separately from persons infected with other strains, thus enabling investigators to focus on the correct group of individuals and more quickly identify the source of an outbreak. PFGE also can be used to characterize bacterial strains in food or the environment to determine whether those strains match the pattern responsible for an outbreak Cluster of undistinguishable pattern Objectives: To detect and investigate outbreaks of foodborne, waterborne, and other enteric illnesses To establish both short-term interventions and long-term control measures to prevent similar outbreaks in the future Dubai Municipality and Dubai Health Authority jointly launched first Foodborne Disease Investigation and Surveillance Program With the disease surveillance system in place, hospitals are able to provide real time reports on suspected foodborne illnesses to the Food Control Department. Investigations are conducted by the department based on these reports. Dubai Municipality and Dubai Health Authority have jointly launched the first project at the national level to investigate cases of transmitted food poisoning and diseases at the start of 2010. Through DHA, the Food Control Department is now linked to all hospitals in Dubai. The hospitals are required to report all suspected foodborne diseases (food poisoning cases) to DHA and the Food Control Department," Surveillance also provides the Food Control Department with the basis for developing, implementing, and evaluating control policies that will lead to reduced rate of illnesses, An active surveillance system will help to identify foodborne diseases that are predominant in Dubai and help focus on the efforts to protect people from those illnesses. Food safety programs for the food industry such as GAPs, GMPs, and HACCP can be further developed based on the surveillance data to prevent contamination of food during its journey from the farm to the table. Surveillance statistics reflect a fraction of cases that occur in the community. Underdiagnosis and underreporting of foodborne illnesses present challenges for surveillance and the detection of outbreaks. “Good surveillance does not necessarily ensure the making of the right decisions, but it reduces the chances of wrong ones.” Dr. Alexander D. Langmuir, 1963 Founder of the Epidemic Intelligence Service One of the aims of improving surveillance is that it should allow a more proactive response to controlling food poisoning. At present much of the response is reactive, i.e. the first indication we have of a new pathogen often comes when people fall ill and it is this that triggers surveys of foods and farm animals. A co-ordinated system would be able to predict with a reasonable degree of confidence the next threat and would thus act as an early warning system. Furthermore, with the identification of foodborne zoonoses in food animals or food products preventative measures could be instituted so that humans do not become ill. Links between foodborne human disease and possible food sources are also required for the early detection of foodborne disease outbreaks. The successful containment of an outbreak also involves links between the surveillance system and the agencies that carry them out. A common definition of food poisoning for the whole country should be worked towards and this should be compatible with that used within other countries. The development of joint standard protocols and guidelines, including a standard notification form for the reporting of notifiable diseases. Continuing education is required for clinicians to encourage more complete and timely Integrated Surveillance- Intersectoral collaborationpromote harmonization of notifiable foodborne diseases within concerned stakeholders. Electronic reporting Regular laboratory sampling, testing protocols and reporting guidelines for foodborne organisms is necessary. The laboratory reporting of foodborne pathogens, currently voluntary, should be made legally notifiable to ensure completeness in reporting of information. In order to improve timeliness of reports and adequate communications, there is an urgent need for an integrated computerized information system and information exchange.