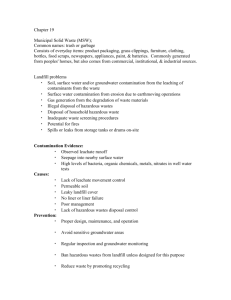

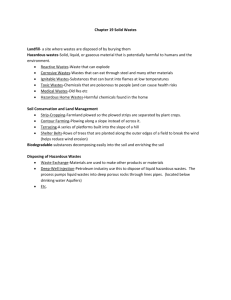

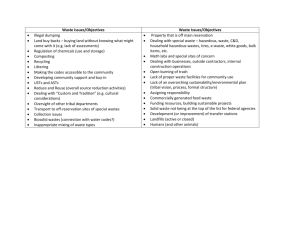

Waste Definitions and Classifications

advertisement