Cuba Sugar industry is on the brink

advertisement

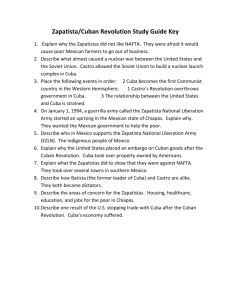

1nc(Brazil) Brazil Economy is on the tipping point but slowly rising-inflation reduction Malinowski 7/1(Mathew Malinowski, Bloomberg Economist, 7/1/13, “Brazil Economists See Higher Selic and Slower Economic Growth”, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-0701/brazil-economists-see-higher-selic-and-slower-economic-growth.html) Brazil economists raised their benchmark interest rate forecast and cut economic growth expectations for this year and next, as inflation persists above the central bank’s target. Brazil’s central bank will raise the Selic to 9.25 percent this year and hold it at that level through 2014, up from the previous week’s forecast of 9 percent for this year and next, according to a June 28 central bank survey of about 100 analysts published today. The economy will expand 2.4 percent this year and 3 percent next year, compared with the previous forecast of 2.46 percent and 3.1 percent, respectively. President Dilma Rousseff’s administration is working to reverse a deteriorating economic outlook in the world’s second largest emerging market. Brazil’s central bank last week cut its forecast for gross domestic product expansion this year, as quickening inflation drags down family and business sentiment. Economic and social discontent has prompted the biggest street protests in decades, as more than a million demonstrators have taken to the streets in the past month to oppose inflation, corruption and poor public services. Swap rates on the contract due in January 2015 were unchanged at 9.87 percent at 9:05 local time. The real strengthened by 0.2 percent to 2.2271 per U.S. dollar. Central bankers, in their quarterly inflation report released on June 27, said inflation will reach 6 percent this year should the benchmark rate remain unchanged at 8 percent, up from a March forecast of 5.7 percent. They also cut the 2013 growth prediction to 2.7 percent, from 3.1 percent. Lifting the embargo allows for investment and trades off with Caribbean and Central American economies Suchlicki 2k(Jaime Suchlicki, Founding Director of the Cuba Transition Project at the Univeristy of Miami and Director of the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies, 6/2000 “ The U.S. Embargo of Cuba”, http://www6.miami.edu/iccas/USEmbargo.pdf) Trade¶ No foreign trade that is independent from the state is permitted in ¶ Cuba. ¶ Cuba would export to the U.S. most of its products, cigars, rum, ¶ citrus, vegetables, nickel, seafood, biotechnology, etc. Yet, since ¶ all of these products are produced by Cuban state enterprises, with ¶ workers being paid below comparable wages, and Cuba has great ¶ need for dollars, the Cuban government could dump products in the ¶ U.S. market at very low prices, and without regard for cost or ¶ economic rationality. ¶ Many of these products will compete unfairly with U.S. agriculture ¶ and manufactured products, or with products imported from If the U.S. were to buy sugar from Cuba, it would be to the ¶ detriment of U.S. or Caribbean producers. 1 Cuban products are not strategically important to the U.S., and are ¶ in the ¶ Caribbean and elsewhere. ¶ great abundance in the U.S. internal market, or from other ¶ traditional U.S. trading partners. ¶ There is little question about Cuba’s chronic need for U.S. ¶ technology, products and services. Yet, need alone does not ¶ determine the size or viability of a market. Cuba’s large foreign ¶ debt, owed to both Western and former Socialist countries, the ¶ abysmal performance of its economy, and the low prices for its ¶ major exports make the “bountiful market” perception a perilous ¶ mirage. ¶ From the U.S. point of view, therefore, the reestablishment of ¶ commercial ties with Cuba would be at best problematic. It would ¶ create severe market distortions for the already precarious regional ¶ economies of the Caribbean and Central America since the United ¶ States would have to shift some of these countries’ sugar quota to ¶ Cuba. It would provide the U.S. market with products that are of ¶ little value and in abundant supply. And, while some U.S. firms ¶ could benefit from a resumed trade relationship, it would not help ¶ in any significant way the overall U.S. economy. Cuba does not ¶ have the potential to become an important client like China, Russia, ¶ or even Vietnam. ¶ Investments¶ Cuba has promoted investments in tourism as its highest priority ¶ and only recently has begun to promote investments in other ¶ sectors. Cuba has not yet attempted to link Foreign Direct ¶ Investments (FDI) with technology transfer. Nor has it permitted 2reater individual freedom in economic matters. While the Cuban ¶ government is allowing some workers to operate independently, ¶ these activities are highly regulated. Unlike China, Cuba has not ¶ legalized private agriculture or manufacturing. ¶ Investments will be directed and approved by the Cuban ¶ government. The Cuban government is unlikely to create a level ¶ plain field for American companies, allowing some to invest while ¶ discriminating capriciously against others. ¶ U. S. investments in Cuba would be limited, however, given the ¶ lack of an extensive internal market, the uncertainties surrounding ¶ the long-term risk to foreign investment, an uncertain political ¶ situation; and the opportunities provided by other markets in Latin ¶ America and elsewhere. Modest initial investments would be ¶ directed primarily to exploiting Cuba's’ tourist, mining, and natural ¶ resource industries. ¶ The Cuban constitution still outlaws foreign ownership of most ¶ properties and forbids any Cubans from participating in joint ¶ ventures with foreigners. ¶ Joint ventures are only permitted with state enterprises; many of ¶ these are now under military control. ¶ It is illegal for foreign companies to hire or fire Cuban workers ¶ directly. Hiring is done by the Ministry of Labor. Foreign ¶ companies must pay the wages owed to their employees directly to ¶ the Cuban government in hard currency. The Cuban government ¶ then pays out to the Cuban workers in Cuban pesos, which are 2orth 1/20 of a U.S. dollar, pocketing 90 percent of every dollar it ¶ receives. ¶ While Cuba's foreign investment law provides protection against ¶ government expropriation, all arbitration must take place in the ¶ corrupt and arbitrary government offices where little protection is ¶ given to the investor. There is no independent judicial system in ¶ the island. ¶ Foreign investors must also confront political uncertainties that do ¶ not exist in many other countries. They must contend with the ¶ possibility of the regime’s reversing policy, the legal questions ¶ surrounding previously confiscated properties, and potential ¶ sanctions against foreign investors that cooperated with the Castro ¶ government in the event that an anti-Castro government comes to ¶ power. ¶ Castro's opposition to market reforms will limit the extent to which ¶ the private sector emerges and functions effectively, and thereby ¶ will slow, if not prevent, attaining a measurable degree of economic ¶ recovery. While Castro and hardliners recognize the need for ¶ economic recovery, they also see the likely erosion of political ¶ power and control that accompanies the restructuring of the ¶ economy along free-market rules. Adoption of market reforms may ¶ well represent a solution to the economic crisis, but a full-blown ¶ reform process carries with it the risk of loss of control over ¶ society, as well as the economy, and threatens to alienate some of ¶ the regime’s key constituencies. 2HY MAINTAIN THE EMBARGO ¶ The embargo should be held as a carrot to be lifted when Cuba ¶ changes its current system and develops a democratic society. The embargo ¶ is not an anachronism but a legitimate instrument of U.S. policy for ¶ achieving the goal of a free Cuba. ¶ While most of the freely elected governments in Latin America pursue ¶ moderate, neo-liberal economic policies, Castro has deliberately staked out a ¶ position as the last defender of Marxism-Leninism. In October 1997 he held ¶ a meeting in Havana of Communist leaders from all over the world to ¶ reassert the supremacy of communist ideology and to plan for a “comeback” ¶ when capitalism fails. ¶ The lifting of the embargo now will be an important psychological ¶ victory for Castro. It would be interpreted as a defeat for U.S. policy and as ¶ an enforced acceptance of the Castro regime as a permanent neighbor in the ¶ Caribbean. ¶ The long held belief that through negotiations and incentives we can ¶ influence Castro’s behavior has been weakened by Castro’s unwillingness to ¶ provide major concessions. Castro prefers to sacrifice the economic well ¶ being of his people rather than cave in to demands for a different Cuba. ¶ Neither economic incentives nor punishment have worked with Castro in the ¶ past. They are not likely to work in the future. 2Not all differences and problems in international affairs can be solved ¶ through negotiations or can be solved at all. There are disputes that are not ¶ negotiable and can only be solved either through the use of force or through ¶ prolonged patience until the leadership disappears or situations change. ¶ Ignoring or supporting regimes that violate human rights and abuse ¶ their population is an ill-advised policy. ¶ The Castro era may be coming to an end if for no other reason than ¶ biological realities. Fidel Castro is seventy-three and deteriorating ¶ physically. U.S. policy should stay the course and wait for Castro’s ¶ disappearance. ¶ The gradual lifting of the embargo now will condemn the Cuban ¶ people to a longer dictatorship and the perpetuation of a failed MarxistLeninist society. ¶ The gradual lifting of the embargo entails a real danger that the U.S. ¶ may implement irreversible policies toward Cuba while Castro provides no ¶ concessions to the U.S. or concessions that he can reverse. ¶ A piecemeal lifting of the embargo will guarantee the continuance of ¶ the present totalitarian political structures and prevent a rapid transformation ¶ of Cuba into a free and democratic society. 2 The lifting of the travel ban without meaningful and irreversible ¶ concessions from the Castro regime could provide the Castro brothers with ¶ much needed foreign exchange. It would represent one of the first steps in ¶ ending the U.S. embargo and prolong the suffering of the Cuban people. PECIFIC ISSUES ¶ If the U.S. has relations with China, why not with Cuba? ¶ Relations with China were propelled by U.S. strategic and economic ¶ interests 1) to counter growing Soviet power; 2) to increase U.S. influence in ¶ Southeast Asia; and 3) to tap the one billion-dollar China market. ¶ Cuba is small, poor, and strategically and economically unimportant. ¶ In Latin America, the U.S. has followed a regional policy that fosters ¶ human rights, neo-liberal economic policies, and democratically elected ¶ civilian governments. U.S.-Cuba policy should be no different. ¶ The U.S. has been willing to intervene militarily in Grenada, Panama, ¶ and Haiti to restore democracy. In Chile it established a military embargo ¶ against the Pinochet dictatorship. In other countries it supported free and ¶ transparent elections. Why should U.S. policy toward Cuba be different? ¶ Aren’t the Cubans also entitled to a free society? ¶ The Cubans are suffering economically because of the U.S. embargo. ¶ The Cubans can buy any products, including food and medicine from ¶ any country in the world. Dollar stores in Cuba have numerous U.S. ¶ products, including CocaCola, and other symbols of American ¶ consumerism. American dollars can purchase almost anything in Cuba. 2There are shortages in Cuba of fruits, vegetables, potatoes, bananas, ¶ mangos, boniatos, and other foodstuffs that have been traditionally produced ¶ locally. What do these shortages have to do with the U.S. embargo? ¶ The reason for Cuba’s economic suffering is a Marxist system that ¶ discourages incentives. As in Eastern Europe under Communism, the failed ¶ Communist system is the cause of the economic suffering of the Cubans, not ¶ the U.S. embargo. ¶ Tourism, trade and investment will accelerate the downfall of Communism ¶ in Cuba as it did in the Soviet Union. ¶ There is no evidence that tourism, trade, or investment had anything to ¶ do with the collapse of communism. Tourism peaked in the Soviet Union in ¶ 1980, almost a decade before the collapse of communism. In the Soviet ¶ Union tourism was tightly controlled with few tourists having any contact ¶ with Russians. ¶ The collapse of Communism was the result of a decaying system that ¶ did not work, the corruption and inefficiency of the Communist Party, the ¶ economic bankruptcy of the Soviet Union in part because of military ¶ competition with the West, an unpopular war in Afghanistan, and the ¶ reformist policies of Mikhail Gorbachev that accelerated the process of ¶ change. ¶ 3he driving force for capitalism in Russia and China is not trade or ¶ investment but a strong domestic market economy, tolerated by the ¶ government and dominated by millions of small entrepreneurs. The will to ¶ liberalize the economy does not exist in Cuba. ¶ Cuba is a potential economic bonanza for U.S. Given Cuba’s scant foreign exchange, its ability to buy U.S. products ¶ remains very limited. Cuba’s major exports, i.e. sugar, tobacco, nickel, ¶ citrus, are neither economically nor strategically important to the United ¶ States. ¶ Lifting the embargo would create severe market distortions in the ¶ already precarious economies of the Caribbean and Central America since ¶ the U.S. would have to divert some portion of the existing sugar quota away ¶ from these countries to accommodate Cuba. The impact of tourism diversion ¶ toward Cuba would profoundly hurt companies. ¶ the economies of the Caribbean and ¶ Central American countries. ¶ Cuba, cited as one of the worst political and commercial risks in the ¶ world by several recently issued country risk guides, lags far behind China ¶ and Vietnam in establishing the necessary conditions for economic ¶ development and successful corporate involvement. Current foreign ¶ investments are small and limited to dollar sectors of the economy such as ¶ the tourist industry and mining. American companies are not “losing out.” ¶ In a free Cuba, U.S. companies will quickly regain the prominent role they ¶ held in pre-Castro Cuba. Specifically-Sugar is Key to brazil’s economy Reuters 12(Leading News Source, “US-Brazil Economyhttp://in.reuters.com/article/2012/08/27/us-brazil-economy-agricultureidINBRE87Q0RV20120827 Agriculture has long been known as the green anchor of Brazil's economy, now the world's sixth-largest. One of the world's breadbaskets, Brazil is a major producer of soybeans, corn, sugar, coffee, oranges and beef, and has invested heavily in the past decade to keep up with surging global demand.¶ But the agricultural sector kicked off 2012 on the wrong foot, adding to the woes of an economy that has been struggling for the past year. Agricultural output contracted 8.5 percent in the first quarter, hit by a drought in the grains belt, a poor sugar cane crop and tight credit markets.¶ The slump in Brazil's farm belt, however, was short-lived. The agricultural sector, which accounts for nearly 30 percent of Brazil's gross domestic product, is expected to be a bright spot when GDP data for the second quarter is released on Friday. Brazil economic stability key to regional stability Cohen 09 [Salu Bernard Cohen. “Geopolitics: The Geography of International Relations.” Rowman & Littlefield. Google Books.158-159. 2009] However, the independence of South America as a geopolitical region is strengthened by Brazil’s continued economic growth, political stability, and world influence. It is clearly the dominant political and economic power within South America and one of the major regional powers of the world. It dwarfs the rest of the continent in population (190 million out of a total of 360 million), in area (3.3 million square miles out of a total of 6.4 million square miles), and in GDP ($1.65 trillion, or over 55 percent). Possessing common borders with every other South American state with the exceptions of Chile and Ecuador, the South American regional giant is geographically positioned to influence and pressure the other states, especially as various transcontinental transportation and energy projects are brought to completion. Factors that favor the economic development prospects of Brazil are the attractiveness of its vast market to investment capital, and its rich natural resources of bauxite, gold, iron, manganese, nickel, phosphates, uranium, timber, and hydropower. It has made rapid strides in petroleum development, and in 2006 the country became completely self-sufficient in oil. Discovery of the vast deepwater Tupi oil field off its southeastern coast followed by discovery of the even larger offshore Carioca field offers the potential for transforming Brazil into a global energy powerhouse. When this oil eventually comes online, the country’s reserves will provide brazil with the additional political weight to country Chavez’s petro-supported foreign policy goals. Now reliant on Bolivia and Argentina for natural gas, Brazil can develop its large offshore gas deposits in the Santos Basin and move toward national self-sufficiency in gas. This would require major investment to double the country’s gas line distribution system, making the timetable for bringing in the gas fields uncertain Latin America instability causes global nuclear war Rochin ‘94 James Rochin, Professor of Political Science, 1994, Discovering the Americas: the evolution of Canadian foreign policy towards Latin America, pp. 130-131 While there were economic motivations for Canadian policy in Central America, security considerations were perhaps more important. Canada possessed an interest in promoting stability in the face of a potential decline of U.S. hegemony in the Americas. Perceptions of declining U.S. influence in the region – which had some credibility in 1979-1984 due to the wildly inequitable divisions of wealth in some U.S. client states in Latin America, in addition to political repression, under-development, mounting external debt, anti-American sentiment produced by decades of subjugation to U.S. strategic and economic interests, and so on – were linked to the prospect of explosive events occurring in the hemisphere. Hence, the Central American imbroglio was viewed as a fuse which could ignite a cataclysmic process throughout the region. Analysts at the time worried that in a worst-case scenario, instability created by a regional war, beginning in Central America and spreading elsewhere in Latin America, might preoccupy Washington to the extent that the United States would be unable to perform adequately its important hegemonic role in the international arena – a concern expressed by the director of research for Canada’s Standing Committee Report on Central America. It was feared that such a predicament could generate increased global instability and perhaps even a hegemonic war. This is one of the motivations which led Canada to become involved in efforts at regional conflict resolution, such as Contadora, as will be discussed in the next chapter. 2nc Links Embargo allows for investment-lifts reprocutions and increases incentives Escandon 8(Jennifer Gerz-Escandon, Writer for The Christian Science Monitor, 10/9/8, “End the US-Cuba embargo: It’s a win-win”, http://www.csmonitor.com/Commentary/Opinion/2008/1009/p09s02-coop.html/(page)/2) Secondly, direct US engagement could allow two of the nation's largest revenue generators, the Cuban nickel and sugar industries, to expand into more capital-intensive energy research through university and private-sector partnerships.¶ Most Cuban exports are currently destined for Canada, China, or the Netherlands as raw or lightly refined materials. Yet, with funding for technology and without the fear of embargo-based repercussions from the US, Cuban research opportunities and export products could have the potential to diversify. ¶ By gaining the freedom and cooperative assistance to make this transition, Cuba could address its own energy dependence while leap-frogging years ahead on modernization. For starters, Cuba could explore the sugar-bioenergy market and the energy-related uses of nickel. Given the abundance of welltrained but under-employed Cuban engineers, the ingredients for a perfect storm of innovation are already present.¶ For its part, by ending the embargo, the US simultaneously gains security through stability in Cuba. More important, by investing in the future prototype for emerging markets – a 42,803-square-mile green energy and technology lab called Cuba – America gains a dedicated partner in the search for energy independence.¶ Embargo is the only restraint on Cuban Sugar Frank 10(Mark Frank, Writer for Financial Times, 5/18/10, “Cuba Worries as Sugar Industry Dissolves”, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/7ae9965e-6290-11df-991f00144feab49a.html#axzz2adOpt5RL) Sugar production is expected to weigh in at around 1.1m tonnes this year, compared with 8m tonnes in 1990 before the Soviet Union collapsed and the poorest result since 1905, according to a rare recent admission by Granma, the Communist party daily.¶ Negotiations are under way with several groups to co-administer some of the eight largest mills, built after the revolution, say foreign business sources and Cubans with knowledge of the industry. It is a big shift in policy under Raúl Castro, president, whose brother Fidel insisted the island knew as much about producing sugar as anyone.¶ A big obstacle is the US Helms-Burton law, penalising investment in properties expropriated from US owners and containing a yet-to-be implemented chapter allowing Cuban-Americans to sue investors who “traffic” in their expropriated properties.¶ All but eight of Cuba’s mills were built before the revolution and therefore nationalised, and most plantations are lands expropriated by the government after Fidel Castro took power in 1959 Lifting the embargo allows for investment-saves the industry Krisher 5(Ben Krisher, B.A. In political Science from University of Vermont, 12/6/5, “Lifting the U.S-Cuban Embargo: A Case of Current Events”, http://voices.yahoo.com/lifting-us-cubanembargo-case-current-events-12262.html?cat=37) A lifting of the embargo would have serious economic consequences for Cuba, allowing businesses in the US and elsewhere to do business on and with the island. This economic opening would certainly benefit the country, which, in the past two years, has experienced a blow to its agricultural sector from a prolonged drought, seriously injuring the sugar industry. Indeed, according to a September 20th, 2005 article in the Carribean and Central American Report, the sugar industry, which used to provide Cuba's "most important export for more than a century" is now being dismantled, and only produced 1.3 million tons of sugar in 2005, a marked decrease from the 8 million tons produced in 1990. Despite agricultural problems, Cuba's Castro has claimed a 9% growth rate for 2005, a figure which, according to a September 6th, 2005 article in Latin American Economy and Business, is artificially high. In fact, the same article identifies a number of problems with A lifting of the embargo would allow US oil companies to do business with Cuba, perhaps relieving some pressure, and would open American markets up to Cuba's nickle deposits, which, according to the Latin American Economy and Business article, are Cuba's economy, including an increasing reliance on the cheap oil provided by Venezuela to keep the economy from collapsing. plentiful. Lifting restrictions allows for investment Conason 8(Joe Conason, Journalist-Writer for Salon, 6/18/8, “One more good reason to lift the Embargo on Cuba”, http://www.salon.com/2008/07/18/cuba_6/) Now there is at least one more incentive to change course. With its huge potential for producing clean, renewable, sugar-based ethanol, Cuba represents a significant source of energy that will remain unavailable to American consumers unless we undo the embargo. Agricultural experts have estimated that Cuba could eventually provide more than 3 billion gallons of fuel annually, perhaps even more when new technologies for extracting energy from sugar cane waste (known as “bagasse”) come online — placing the island third in world ethanol production, behind the U.S. and Brazil. Given the relatively small demand for auto fuel in Cuba, nearly all of that ethanol would be available for export to its nearest neighbor.¶ Today the Cuban government manufactures only nominal amounts of ethanol, mainly because of government policies favoring table sugar and rum instead. Fidel Castro reportedly feels that using cane for fuel instead of food is a capitalist crime against the poor. Having ceded power to his brother Raúl, however, the aging ruler may no longer control economic policy — and Raúl is widely viewed as the more flexible and pragmatic Castro. A revitalized ethanol industry in Cuba would have an enormous ready market only 90 miles away. It is also worth noting that sugar ethanol not only seems to burn cleaner than the kind made from grain but could also reduce pressure on food prices. (Besides, everyone would be better off eating less sugar.) ¶ Like offshore oil, Cuban ethanol would not be available overnight. Sugar production has dropped precipitously under Castro and Cuba lacks substantial biorefinery capacity. Whether that capacity can be constructed faster than Exxon can find oil and build platforms is an open question. But the difference is that Cuba could certainly grow far more sugar cane than it does currently. And once the oil is gone, there will be no more, while cane can grow year after year indefinitely — without contributing to climate change or polluting the oceans. Cuba Sugar industry is on the brink-Investment key to growth Grogg 13(Patricia Grogg, Writer for the Inter Press Service-News Agency, 1/9/13, “Cuban Sugar Sector Aims for Recovery in 2013”, http://www.ipsnews.net/2013/01/cuban-sugar-sector-aimsfor-recovery-in-2013/) The Cuban sugar industry seems to be experiencing a rebirth thanks to an economic modernisation programme that has allowed for an injection of foreign capital as part of a strategy to strengthen and diversify this key sector.¶ “There is a recovery, an awakening in the production of sugar cane, sugar and sugar derivatives,” said specialist Liobel Pérez from the state-owned business group Azcuba, created just over a year ago to replace the once powerful Ministry of Sugar. Azcuba’s effectiveness will be put to the test in 2013 as it implements new forms of management in the sector.¶ Foreign investment in the sugar industry was formerly limited to a handful of sugar derivative enterprises. Its extension to sugar production was one of the innovations introduced by Azcuba in 2012. “There are two major investments which complement the measures that have contributed to sustained growth in production,” Pérez told IPS.¶ The contract between COI and Empresa Azucarera Cienfuegos, an Azcuba subsidiary, is for joint management over the next 13 years of the 5 de Septiembre sugar mill, located in the province of Cienfuegos, 232 km southeast of Havana.¶ The Brazilian company will invest in agricultural mechanisation to raise crop yields and in industrial processing technology.¶ It is hoped that this injection of capital will “optimise human and industrial resources” and thus help the Cienfuegos mill to raise production to the 90,000 tons per harvest for which it was designed, from the 25,000 to 30,000 tons it has produced in recent years.¶ As for Havana Energy, it is entering into a joint venture with Azcuba subsidiary Zerus SA to build a biomass power plant near the Ciro Redondo sugar mill in the province of Ciego de Ávila, in central Cuba.¶ The plant will be built with an investment of between 45 million and 55 million dollars, and is scheduled to begin generating electricity in 2015. During the harvest, it will be powered with the sugar cane bagasse left over after sugar processing. The rest of the year, it will run on marabu weed, which has taken over large areas of idle farmland in the country.¶ A number of other foreign investment projects are being studied, involving joint management, which seems to be Cuba’s preferred strategy for sugar mills.¶ However, other potential joint venture initiatives are also being considered, “primarily in the energy and sugar derivatives sectors,” said Pérez.¶ Sugar cane is a source of a wide array of derivatives used in the food, chemical, pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. The long list of by-products includes animal feed, resins, preservatives, plastics and raw materials for paper and furniture production.¶ “Cuba has over 400 years of experience in sugar cane cultivation, as well as trained human resources, facilities, land, scientific research centres, infrastructure and organisation. What it lacks is technology and, above all, the money to buy it,” explained Pérez.¶ He believes that what is most important is the “new vision” of how the recovery of the sector can be achieved, which makes it possible to speak of sustained growth in sugar production, he said. ¶ Pérez preferred not to hazard an estimate for the 2012-2013 harvest, which began in November of last year with the so-called “small harvest” and will continue until May, with the participation of 50 sugar mills. He did however indicate that production is expected to be 20 percent greater than last year’s.¶ Other sources close to the sugar sector said that the current harvest should yield enough cane to produce 1.8 million tonnes, although the plan is to produce just over 1.6 million. Sugar continues to be the leading product but not the only one produced by this industry which was the mainstay of the centralised Cuban economy until the late 20th century. Cuba Sugar industries need foreign investment-new tech Garcia 13 (Jose Garcia, Economist, 6/14/13, “Economists Assess Challenges of Cuban Sugar Sector”, http://www.periodico26.cu/index.php/en/cuba-news/9228-economists-assesschallenges-of-cuban-sugar-sector) Gathered in working commissions at Havana's International Convention Center, academics, experts and officials addressed the importance of the sugar industry for the country's economic and social development and the need to find ways for its recovery.¶ Economist Jose Antonio Garcia said that all sugar mills must undergo a thorough testing stage before joining the harvest, pointing to the breakdown of a boiler in a sugar plant in the province of Mayabeque, two days after beginning the harvest.¶ The expert also called for having sugar cane plantations nearer the industry, bearing in mind the properties of the soil, selecting the seeds appropriately, guaranteeing the repair of all equipment used in the harvest, and having a larger participation by research centers.¶ Finance and Price Minister Alfredo Alvarez said that sugar workers must be paid according to the prices of the product on the world market, and in tune with the diversification of the sector, since many of the products are exported and others generate electrical power from biomass.¶ Economist Jose Luis Rodríguez said that there is a lot of efficiency to recover in the sector, particularly in the production of sugar cane derivatives. He also stressed the need for foreign investment to obtain new technologies. An end to the embargo would result in cheaper sugar Knapp 9 (Thomas Knapp, Senior news Analyst at the Center for Stateless Society-Think tank, 2009, “Who Benefits From the US Trade Embargo of Cuba?,” Online, http://c4ss.org/content/1369) What would be the result of an end to the embargo — assuming, as it is never safe to do, that both governments were actually willing to drop it into the wastebasket of history? On the economic side, consumers and non-rent-seeking producers in both countries would benefit. Sugar in particular would get cheaper in the US as American producers were forced to compete in an open market instead of being “protected” from Goods of all types would get cheaper in Cuba as American imports which only have to be shipped across 90 miles of ocean arrive to compete with their European equivalents. Producers in both countries would have new markets opened to them, and capital from both countries would have new, competitive places to flow to. Cuban cane. US businesspeople want to invest in Cuba—embargo is the only thing stopping them Wall Street Journal 12 (2012,“Investing in Cuba: Good Luck With That,” http://blogs.wsj.com/totalreturn/2012/03/26/investing-in-cuba-good-luck-with-that/) a story about a closed-end mutual-fund manager who has been waiting nearly 20 years for the opportunity to invest directly in Cuba. Indeed, the business opportunity seems tempting: 90 miles south of Key West, Florida is an island of more than 11 million people with infrastructure that’s seen little update since the 1960s. That’s led many a businessman to dream of the day when he or she could get exposure to that market. Of course, there’s a daunting hurdle: The U.S. has banned most business with Cuba since 1962. As a result, it is near impossible for ordinary investors to get more than minimal exposure to Cuba, according to lawyers and investment This weekend, we wrote advisers. In 1958, as Fidel Castro’s revolutionaries fought the Cuban government, the U.S. imposed an arms embargo. After Mr. Castro took power and his government aligned The restrictions have remained mostly in place, though the Obama administration has eased restrictions on travel and money sent to family members Cuba. U.S. companies in certain industries, such as food, medical supplies, and entertainment can do business in Cuba if they get the proper licenses with the Soviet Union, the U.S. broadened the trade limits. from the U.S Treasury Department and the U.S. Commerce Department, said Erich Ferrari, a lawyer based in Washington who specializes in U.S. economic sanctions. Even so, the penalties for violating the embargo are severe: between $65,000 and $100,000 in fines and 10 years in prison The sugar industry in Cuba seeks foreign investment Peters 3 (Phillip Peters ,degrees from the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and the Georgetown University Graduate School, International Studies, 2003, “Cutting Losses: Cuba Downsizes its Sugar Industry,” http://www.lexingtoninstitute.org/library/resources/documents/Cuba/ResearchProducts/cuttin g-losses.pdf) The sugar ministry is actively seeking foreign investors to boost production of derivatives,¶ and officials use Cuban workers’ educational level and the nation’s scientific infrastructure,¶ low production costs, location, and the markets’ growth potential as selling¶ points. They say they see substantial interest among potential partners. “There are more¶ foreign capitalists that come to make offers than those we seek out,” claims one official. U.S. investment and bilateral cooperation with Cuba key to Cuba’s sugarcane ethanol industry Perales 10 (Jose Raul Perales, senior program associate of the Latin American Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2010, “The United States and Cuba: Implications of an Economic Relationship,” http://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/LAP_Cuba_Implications.pdf) it is in the best interest, of both Cuba and the United States to begin energy collaboration today. What is needed, Piñón continued, is a bilateral policy that would contribute to Cuba’s energy independence as well as support a broader national energy policy that embraces modernization of infrastructure, the balancing of hydrocarbons In spite of these developments, Piñón argued with renewable materials, and conservation and environmental stewardship. He highlighted the case of the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, and what would happen if such an incident happened in a Cuban oil rig (under current U.S. policy banning equipment and technological sales to the island), as a reminder of the need for an if U.S. companies were allowed to contribute to developing Cuba’s hydrocarbon reserves, as well as renewable energy such as solar, wind, and sugarcane ethanol, it would reduce the influence of autocratic and corrupt governments on the island’s road toward self determination . Most importantly, it would provide the United States and other democratic countries with a better chance of working with Cuba’s future leaders to carry out reforms that would lead to a more open and representative society. American oil and oil equipment and service companies have the capital, technology, and operational know-how to explore, produce, and refine in a safe and responsible manner Cuba’s potential oil and natural gas reserves. In terms of specific U.S. industries, agribusiness is pushing for a lifting of certain restrictions in the U.S. embargo in order to increase its participation in the Cuban market, explained Chris Garza, senior director of congressional relations at the American Farm Bureau. At present the industry has not been able to see its full potential in Cuba due to existing restrictions. U.S. agribusiness is not demanding that the embargo against Cuba be lifted; rather, it seeks key concessions to ensure that U.S. firms can better compete in the Cuban market. Indeed, Garza energy dialogue between Cuba and the United States. Moreover, Piñón contended that highlighted how U.S. businesses can sell agricultural products to other U.S.-sanctioned countries and U.S. citizens can travel to such countries. In this sense, agribusiness is not seeking drastic changes to U.S. foreign policy; it is merely asking for the ability to treat Cuba as it does other countries subject to U.S. economic and other sanctions. Cuba in need of foreign investment to build ethanol industry Specht 4/24 (Jonathan Specht, BA from University of California Davis, 4/24/13, “Raising Cane: Cuban Sugarcane Ethanol’s Economic and Environmental Effects on the United States”, http://environs.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/36/2/specht.pdf) because Cuba’s ethanol industry is currently almost nonexistent, ¶ it will need a great deal of foreign expertise and investment to get¶ started. However, such investments are unlikely to be made unless Cuba makes ¶ fundamental changes in its business climate. In the words of Gonzalez and ¶ McCarthy, “[C]apital investment, which Cuba’s economy desperately needs and ¶ which is most likely to be supplied by foreign investors, will be difficult to¶ attract without enforceable contracts, access to neutral adjudication of disputes, ¶ and a degree of predictability that has heretofore been lacking.”54 Any post-¶ Castro government will likely begin to make such changes to increase the appeal¶ of the island nation to foreign investment. However, Additionally, implementing these¶ changes will take time and trial and error, which will slow the creation of a ¶ sugarcane-based ethanol industry. The 2012 drought supplies even more incentive to withdraw the embargo and invest in the Cuban sugar industry Specht 4/24 (Jonathan Specht, BA from University of California Davis, 4/24/13, “Raising Cane: Cuban Sugarcane Ethanol’s Economic and Environmental Effects on the United States”, http://environs.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/36/2/specht.pdf) The drought of 2012 not only highlighted the drawbacks of the U.S. ethanol status quo, but also the importance of not abandoning biofuels in general. The¶ 2012 drought substantiated criticisms that the current corn- based system of ethanol production is flawed. Yet, policy-makers should not automatically respond by withdrawing federal government support for the creation of bio- based alternatives to fossil fuels. Given that the RFS would be critical for future¶ development of a Cuban sugarcane-based ethanol industry, the abolition of this standard that some have called for would have long-lasting effects.¶ While it is currently impossible to blame any single climatological event on climate change, even one as large as a major regional drought, scientists have long predicted that such droughts as the Midwest experienced in 2012 are the type of events that will result from climate change.192 Adding to the already overwhelming evidence that climate change is occurring (and should no longer be a matter of debate),193 July 2012 was the hottest month the United States has experienced in 118 years of meteorological records.194 The key to halting (or at least slowing) climate change will be to keep as large an amount as is possible of the carbon stored in fossil fuels — coal, oil, and natural gas — in the ground and out of the atmosphere.195 By providing an alternative to petroleum, biofuels can help to reduce oil consumption and therefore aid in the extremely important challenge of keeping carbon underground. ¶ As the United States faces the twin challenges of climate change and peak oil, biofuels must be a part of the solution. However, it is imperative that policies promoting biofuels are capable of accomplishing the United States’ environmental and energy goals. Neither a wholesale abandonment of federal involvement in the development of biofuels nor a continuation of the corn- centric status quo is an acceptable way forward. The development of a Cuban sugarcane-based ethanol industry is part of a potential solution. Whether the former incentives for the domestic ethanol that expired at the end of 2011 will be revived by a future Farm Bill remains to be seen. Even if they are not, as long as the U.S. trade embargo against Cuba continues there will be little chance of that country making a substantial investment in the development of an entire new industry. It is understandable, for face-saving reasons, that United States¶ policy-makers would not consider ending the decades-long trade embargo against Cuba as long as Fidel Castro remains alive.196 But, as soon as possible after a governmental transition begins in Cuba, United States policy-makers taking steps to encourage the creation of such an industry.¶ should consider I/L Sugar Key Brazil No alt causes to growth-agriculture is the base for future diversity-Dutch disease Sapp 12(William Sapp, Writer for Geopolitical Monitor, 2012 “The Fragility of Brazil’s Economic Strength”, http://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/the-fragility-of-brazils-economic-strength-4657) When a significant segment of a country’s economy is based around raw material exports, inflows of foreign capital tend to artificially raise the value of the domestic currency. The result is inflation and an increased reliance on international savings to finance growth. In theory, capital flows from developed nations should be welcomed in developing economies like Brazil. After all, foreign capital can improve social welfare and increase industrial diversification. But, in practice, the negative effects of a commodity based economy often outweigh the positive. ¶ Dutch disease is not a new phenomenon in Brazil. Whether sugar, coffee, gold or rubber, the Brazilian economy has frequently been a prisoner of the boom and bust nature of commodities. Since its independence in 1825, Brazil has defaulted on (or “restructured”) its debt a staggering seven times. Indeed, it would be more appropriate to call the economic phenomenon ‘Brazilian disease’ considering the nation’s long history of economic turmoil. ¶ Of course, the Brazilian economy of today is significantly different from the Brazil of the past. Its economy, which for centuries has been based on the exportation of a “small number of primary products,” now reads like a weekend shopping list. Brazil is the world’s leading exporter of poultry, beef, orange juice, coffee, and sugar and the world’s second leading exporter of soybeans and iron ore. In terms of monetary value, its top five exports are iron ore, oil & fuel, transport equipment (aircraft), soy, sugar, and ethanol. ¶ Despite Brazil’s impressive portfolio of export commodities, economists remain concerned – largely because of the recent discovery of the 800 km pre-salt deep water oil reserves off the Brazilian coast. In a recent Financial Times article, former Petrobras President Sergio Gabrielli, estimated that the oil industry will grow from around 10% of GDP to an astounding 25% in coming decades. Whether this unprecedented project – estimated to attract 1 trillion (USD) in capital investment over the next decade – turns into an economic windfall or an economic oil spill for the Brazilian people will largely depend on the government’s economic decisions in the next few years.¶ On March 13th the Brazilian government amped up its protective measures, and broadened its tax on financial operations (IOF) by levying a 6% tax on foreign loans and bonds that exit Brazil within five years. According to Mantega, the goal is to curb “the inflow of speculative capital” that enters Brazil seeking to capitalize on the difference between interest rates in developed countries and Brazil. The IOF may well contain inflation for the 2012 financial year: the real is currently hovering at approximately (BRL) $R 1.8 to the USD (from a high of (BRL) $R1.53 in July 2011) and is expected to plateau at (BRL) $R2.0 to the dollar by the end of the 3rd quarter. ¶ Regardless of whether Brazil’s manufacturing sector returns to previous levels of production or continues to decline, the price of commodities should remain stable in the short-term. As an economic immunization shot, the Brazilian government might heed the advice of legendary economist Edmar Bacha who recommends creating an oil sovereign fund – in the Chilean model - that would function as an economic buffer protecting the nation against commodity volatility. ¶ If the Brazilian government fails to implement significant economic safeguards, there is the unpleasant possibility that the country’s Dutch disease, currently in remission, may indeed recur. Even if sugar isn’t key-the ethanol it produces fuels the economy Neves 13(Marcos Fava Neves, Professor of Business at Unviersity of Sao Paulo, Expert on Global Ag Business, 4/11/13, “Sugar cane vital to Economy”, http://www.energyforecastonline.co.za/articles/sugar-cane-can-fuel-economy) The impacts for agrifood system participants are hard to ignore.¶ Farmers and agribusiness companies are now expected to reduce their environmental footprint, to increase transparency and facilitate a better flow of information, to be better governed and promote corporate social responsibility, to be more inclusive, and to be better stewards of the environment and increase the usage of renewable energy sources.¶ The legitimacy of agribusiness firms – and entire agrifood value chains – is not only dependent on economic factors but also on social and environmental sustainability. Simply put, in the 21st century planet and people matter as much as profits.¶ The role of biofuels in delivering sustainability¶ Some researchers suggest that biofuels could play a big part in the solution for poor countries to diversify business and ensure sustainable development.¶ Several countries that implemented biofuels development programmes have experienced significant job creation, especially in rural areas but also along the value chain.¶ The International Labour Organization estimates the number of jobs created in the renewable energy sector will double by 2020 with about 300 000 new jobs.¶ In the early phase of the bio-ethanol programme in the US, around 147 000 jobs were created in different sectors of the economy.¶ This short article outlines some potential benefits of biofuel development in Africa.¶ The development of the sugarcane industry in Brazil may serve as a model.¶ The industry output is impressive: 550 million metric tons of sugarcane is used as raw material to produce 31 MMT of sugar (equivalent to 20% of world production), 27 billion liters of ethanol (30% of world production) and bio-electricity.¶ Ethanol production alone creates 465 000 direct jobs, which is six times larger than the oil industry in Brazil. Ag Key to Brazil Econ Waring 13(David Waring, Writer at ForexNews, 3/14/13, http://www.forexnews.com/blog/2013/03/14/brazilian-economy/) Agriculture represents 5.5% of the brazilian economy and employs 15% of the workforce, approximately 10 million people. Brazil is often called the food basket of the world and for good reason, many of the products you take for granted are actually produced in Brazil.¶ Sugar cane is by far Brazil’s biggest food export, it’s responsible for 6.5% of overall exports. This is followed by soybeans (5.4%), poultry (2.9%), coffee (2.6%), bovine meat (1.6%) and fruit juice (1.6%).¶ The agricultural sector in Brazil is one of the fastest growing sectors, growing at a rate of 9.6% annually. This rapid growth comes at a cost however. There is continued pressure on Brazil to increase its arable land stocks. US Wont Increase Quotas US wont increase sugar quotas Josephs 13(Leslie Josephs, Writer for Wall Street Journal, 2/19/13, “U.S. Unlikely to Raise Sugar-Import Quota”, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323495104578314510772923662.html) The U.S. government is unlikely to raise the quota for no- or low-tariff sugar imports for the first time in four years, due to increased domestic production, a person who works for the U.S. Department of Agriculture said Tuesday.¶ Big U.S. sugar production is mirroring the global market, where output is expected to outpace demand this season. If the U.S. buys less of the sweetener from the global market, it could put more pressure on sugar prices, which have been trading near 30-month lows.¶ While U.S. sugar cane and sugar beet growers produce most of the country's supply of the sweetener, the World Trade Organization requires the U.S. to allow a minimum of 1.23 million short tons of no- or low-tariff raw-sugar imports each year. Whether that much sugar is brought into the U.S. depends on demand and market prices. The U.S. usually chooses to allow more than the minimum, a decision the USDA makes after April 1.¶ "It's highly unlikely that there would be any quota increases in the current market situation," the person said.¶ The last time the U.S. didn't raise the tariff-rate quota, or TRQ, for raw sugar was the 2009 fiscal year, according to the USDA.¶ Favorable weather in major sugar cane- and sugarbeetgrowing areas are expected to lift production this season, as well as those in Mexico. Under the North American Free Trade Agreement, the U.S. can import sugar duty-free from its southern neighbor.¶ A mild winter, timely rains and dry harvesting weather in late 2012 helped production reach a record, said Jim Simon, general manager of the American Sugar Cane League, an industry group that represents 450 farms in Louisiana.¶ The USDA estimates Louisiana will produce 1.7 million short tons of sugar this season, which Mr. Simon said was "a record." Louisiana is the second-largest sugarcane-growing state, after Florida.¶ The U.S. consumes 11.5 million short tons of sugar annually. Cuba Spills Over A Cuban Sugar Ethanol Industry Would Be World Class if Developed. Specht 4/24 (Jonathan Specht, BA from University of California Davis, 4/24/13, “Raising Cane: Cuban Sugarcane Ethanol’s Economic and Environmental Effects on the United States”, http://environs.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/36/2/specht.pdf) To speak of a Cuban sugarcane-based ethanol industry is, at this point, largely a matter of speculation.46 Because of the anti-ethanol views of Fidel Castro (who has said that ethanol should be discouraged because it diverts crops from food to fuel),47 Cuba currently has almost no ethanol industry. In the words of Ronald Soligo and Amy Myers Jaffe of the Brookings Institution, “Despite the fact that Cuba is dependent on oil imports and is aware of the demonstrated success of Brazil in using ethanol to achieve energy self-sufficiency, it has not embarked on a policy to develop a larger ethanol industry from sugarcane.”48 There is, however, no reason why such an industry cannot be developed. As Soligo and Jaffe wrote, “In addition, Cuba has large land areas that once produced sugar but now lie idle. These could be revived to provide a basis for a world-class ethanol industry. We estimate that if Cuba achieves the yield levels attained in Nicaragua and Brazil and the area planted with sugarcane approaches levels seen in the 1970s and 1980s, Cuba could produce up to 2 billion gallons of sugar-based ethanol per year.”49 Cuba is the ideal area in which to grow sugarcane for ethanol, but needs investment Specht 4/24 (Jonathan Specht, BA from University of California Davis, 4/24/13, “Raising Cane: Cuban Sugarcane Ethanol’s Economic and Environmental Effects on the United States”, http://environs.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/36/2/specht.pdf) To speak of a Cuban sugarcane-based ethanol industry is, at this point, largely a matter of speculation.46 Because of the anti-ethanol views of Fidel Castro (who has said that ethanol should be discouraged because it diverts crops from food to fuel),47 Cuba currently has almost no ethanol industry. In the words of Ronald Soligo and Amy Myers Jaffe of the Brookings Institution, “Despite the fact that Cuba is dependent on oil imports and is aware of the demonstrated success of Brazil in using ethanol to achieve energy self-sufficiency, it has not embarked on a policy to develop a larger ethanol industry from sugarcane.”48 There is, however, no reason why such an industry cannot be developed. As Soligo and Jaffe wrote, “In addition, Cuba has large land areas that once produced sugar but now lie idle. These could be revived to provide a basis for a world-class ethanol industry. We estimate that if Cuba achieves the yield levels attained in Nicaragua and Brazil and the area planted with sugarcane approaches levels seen in the 1970s and 1980s, Cuba could produce up to 2 billion gallons of sugar-based ethanol per year.”49¶ The ideal domestic policy scenario for the creation of a robust Cuban sugarcane ethanol industry would be a situation in which: the U.S. trade embargo on Cuba is ended; U.S. tariff barriers are removed (in the case of sugar) or not revived (in the case of ethanol); and the RFS requiring that a certain percentage of U.S. fuel come from ethanol remain in place. Of course, changes in United States policy alone, even those that ensure a steady source of demand for Cuban sugarcane-based ethanol, would not be enough to create an ethanol industry from scratch. Cuba will need to foster the industry as a key goal of the post-Castro era and shape its domestic policies to encourage the growth of the industry.¶ Given that the Cuban sugar industry lived and died by its ties with the Soviet Union for several decades of the Twentieth Century,50 Cuba will likely be quite wary of investing too much in the creation of a sugarcane ethanol industry that it perceives as being largely a creature of U.S. energy and agricultural policy. Therefore, the creation of a significant sugarcane ethanol industry in Cuba will require a large increase in domestic demand for ethanol. One way that Cuba could encourage domestic demand for ethanol would be to follow the Brazilian model of encouraging the purchase of Flex Fuel vehicles, which can run on any blend of fuel between 100% gasoline and 100% ethanol.51 Given the relative poverty of Cuba’s population, as indicated by the number of vehicles in the country that are several decades old,52 expecting new vehicles to provide a source of demand for ethanol may be an extremely unrealistic prospect. On the other hand, potential pent-up demand for new automobiles, alongside sufficient and well-directed government incentives, could accelerate demand for Flex Fuel vehicles relative to other countries.¶ Like all new capitalist industries to emerge in the post-Castro era, whatever ethanol industry arises will have to deal with the painful transition from socialism to capitalism. The Cuban sugarcane ethanol industry will face similar challenges to other private sector industries that arise in the post-Fidel era. One of these challenges will be simply a lack of people with skills necessary for any industry. According to Edward Gonzalez and Kevin McCarthy of the RAND Corporation, “[A]s a result of 40-plus years of communism, the labor force lacks the kinds of trained managers, accountants, auditors, bankers, insurers, etc., that a robust market economy requires.”53 While these challenges will not be unique to Cuba’s ethanol industry, they will put the country at a competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis existing ethanol exporters such as Brazil. This will be especially true if there is a significant lag time between the expiration of the ethanol tariff barriers at the end of 2011 and the eventual removal of the United States trade embargo against Cuba.¶ Additionally, because Cuba’s ethanol industry is currently almost nonexistent, it will need a great deal of foreign expertise and investment to get started. However, such investments are unlikely to be made unless Cuba makes fundamental changes in its business climate. In the words of Gonzalez and McCarthy, “[C]apital investment, which Cuba’s economy desperately needs and which is most likely to be supplied by foreign investors, will be difficult to attract without enforceable contracts, access to neutral adjudication of disputes, and a degree of predictability that has heretofore been lacking.”54 Any post- Castro government will likely begin to make such changes to increase the appeal of the island nation to foreign investment. However, implementing these changes will take time and trial and error, which will slow the creation of a sugarcane-based ethanol industry. Aff answers Imported Cuban biofuel would trade off with corn ethanol production in the US(US Biofuels impacts) Specht 4/24 (Jonathan Specht, BA from University of California Davis, 4/24/13, “Raising Cane: Cuban Sugarcane Ethanol’s Economic and Environmental Effects on the United States”, http://environs.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/36/2/specht.pdf) Unless Congress raises the RFS by a sufficient degree to absorb all domestic ethanol production on top of these new imports, the increase in such imports would likely damage the domestic ethanol industry. “Whatever the level or type of biofuel, increased imports (holding other factors constant) would reduce the quantity of domestically produced biofuels, which would reduce the demand for biofuel feedstocks.”138 Because very little ethanol is currently imported into the United States, law and policy changes that successfully fostered the development of a Cuban sugarcane-based ethanol industry would have a significant economic impact on the United States. Such a change would have the largest economic effect on two regions: the Midwest, which is currently the primary source of ethanol production in the United States, and the Southeast, especially Florida. This Part of the Article will discuss the likely economic effects of such policy changes first on the Midwest, then on Florida, then on the United States generally. Sugar Ethonal solves fossil fuels(add warming or oil dependence impacts) Newsweek 7 (“Sugar Rush,” 2007, http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2007/04/15/sugar-rush.html) He won't be the last. Thanks to global climate change, sugar now is in big demand. The drum-beat of alarm over global warming has set businesses clamoring for a piece of the sugar-cane action. There are plenty of other ways to make ethanol, of course, and scientists the world over are busy tinkering with everything from switchgrass to sweet potatoes. U.S. farmers make it from corn, but with the scarcity of arable land there's just so much combination of limited land and surging demand have sent corn prices through the roof). So far nothing beats sugarcane— which grows in the tropics—for an abundant, cheap source of energy. Unlike beets or corn, which are confined to temperate zones and must be transformed into carbohydrates before they can be converted into sugar and finally alcohol, sugarcane is already halfway there. That means the sugar barons like Ometto spend much less energy than the competition, not to mention money. The moral imperative of finding a substitute for fossil fuels has lent an air of respectability to new ventures to produce biofuels from sugar—a marked contrast to the sugar barons of old, known for their they can plant without crowding out other premium crops, like soy beans. (Meantime, the ruthless ways and their appetite for taxpayers' money. "The distillers who ten years ago were the bandits of agribusiness are becoming national and world heroes," Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Lula declared recently. "[E]thanol and biodiesel are more than an answer to our dangerous 'addiction' to fossil fuels. This is the beginning of a reassessment of the global strategy to protect our environment." Changes in US Policy Are Not Enough To Create a Cuban Ethanol Industry Specht 4/24 (Jonathan Specht, BA from University of California Davis, 4/24/13, “Raising Cane: Cuban Sugarcane Ethanol’s Economic and Environmental Effects on the United States”, http://environs.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/36/2/specht.pdf) The ideal domestic policy scenario for the creation of a robust Cuban sugarcane ethanol industry would be a situation in which: the U.S. trade embargo on Cuba is ended; U.S. tariff barriers are removed (in the case of sugar) or not revived (in the case of ethanol); and the RFS requiring that a certain percentage of U.S. fuel come from ethanol remain in place. Of course, changes in United States policy alone, even those that ensure a steady source of demand for Cuban sugarcane-based ethanol, would not be enough to create an ethanol industry from scratch. Cuba will need to foster the industry as a key goal of the post-Castro era and shape its domestic policies to encourage the growth of the industry. Brazil Econ Resilient Rathbone 12(John Paul Rathbone, Economist at the Financial times, 9/20/12, “Mantega says Brazil’s economy resilient”, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/91677578-0341-11e2-bad200144feabdc0.html#axzz2ajYEh3nX) Brazil’s economy is more resilient than other big countries and its economic development model “more consistent” too, he says.¶ It is a contentious position given that Brazil’s economy, until recently a market darling and many investors’ favourite among the so-called Bric nations of it, Russia, India and China, has lurched from boom to near stagnation. The world’s sixth-biggest economy is expected to expand by 1.6 per cent this year, after 7.5 per cent in 2010. Still, Mr Mantega says Brazil is now back on the right track, despite difficult global conditions.¶ “We are taking measures to ensure that growth is long-term,” he said, forecasting a return to an annual growth rate of 4 per cent by the year end, “even with Europe close to recession and the US economy moving sideways.”¶ Be that as it may, many have questioned Brazil’s growth model of late and wondered how sustainable it is. For the past decade, Brazil has surfed the global commodity boom. At home, it has enjoyed an explosion of credit-driven consumption.¶ Critics say these drivers have now run out of steam and, to compensate, Brazil has increasingly turned to the state rather than the private sector to provide growth. Furthermore, Brazil is held back by an over-regulated labour market, a highly complex tax system and crumbling infrastructure.¶ Mr Mantega says that is looking at Brazil “through a rear-view mirror” and, besides, when the state does act it is to provide a counter-cyclical boost or to step in when the market fails. He cites the example of Banco do Brasil, a state-controlled bank that enjoys private-sector levels of profitability, but that on recent government orders cut lending spreads. Competing private banks soon followed suit.¶ The 63-year old also reacts adroitly to charges that Brazil’s occasionally erratic growth path is a result of ad hoc state intervention and that other Latin American countries, such as Chile or Mexico, achieve more consistent growth with more market-friendly policies.¶ “I don’t call this chicken flight,” he says, whipping out a chart, handwritten on a piece of lined notepaper, which compares Brazilian growth with Mexico’s over the past six years. It shows that Brazil averaged 4.2 per cent and Mexico 2.1 per cent. At least by that measure, even though it is backward looking, Brazil is in the lead.¶ What of the future? Mr Mantega says a series of recent measures – from cuts in payroll taxes to lower electricity tariffs and a $66bn package of new privately operated infrastructure projects – will reduce the infamous “custo Brasil”, the high cost of doing business in Brazil.¶ “This is not wishful thinking. This is something that is already taking place,” he says. “We are going to continue reducing costs and taxes.”¶ The result will be a more competitive economy, a theme much on his mind as the US, Japan and Europe embark on their latest round of quantitative-easing policies. These, though, will have little effect on their home economies, he says, but will inevitably led to beggar-thy-neighbour devaluations and growing trade friction. Brazil economy down-mulitple warrants Seibt 13(Sebastian Seibt, Writer for Franch24, 6/20/13, “Behind the Protests, Brazil’s dysfunctional Economy”, http://www.france24.com/en/20130620-brazil-protests-sao-paulodilma-rousseff-world-cup-economy-inflation) The increase in bus ticket prices (0.20 real, or 0.06 euros) is symptomatic of the inflation that has been plaguing Brazil for several months. “Prices are going up at a rate higher than 6% per month, which is higher than the 4.5% objective established by the government,” explained Christine Rifflart, an economist specialised in Latin America at the French Economic Observatory (OFCE).¶ The rise in public transportation costs is part of a larger increase in the cost of living in Brazil. Prices of basic goods like tomatoes rose by as much as 90% in a year, for example. Rent has also been on the rise over the past several years, increasing by an average of 120% since 2008. “This inflation is essentially due to the increase in salaries,” Rifflart pointed out.¶ Consequently, the poorest Brazilians – those whose salaries have not risen – are getting poorer.¶ “Brazil remains one of the countries with the highest level of inequality when it comes to salary and access to social services,” noted Jérémie Gignoux, an economist at the Paris School of Economics.¶ If the Brazilian government succeeded in significantly lowering the poverty rate in the country, which went from 34% of the population in 2004 to 22% in 2009, authorities today are having a difficult time stopping the spiralling inflation.¶ The government is indeed stuck between two, somewhat conflicting priorities: the need to fight inflation and the need to stimulate the economy so that it is healthy again. Brazil’s economy, the seventh largest, grew “by only 0.9% in 2012, essentially because of low export levels,” Rifflart said – compared to an average annual growth rate of 3.6% over the past decade.¶ In order to revitalise the sale of Brazilian products abroad, the government could lower its currency rate in order to make exports less expensive, but that could end up worsening inflation.¶ The World Cup: a bitter pill to swallow¶ But it is not so much Brazil’s poorest residents who are in the street marching in protest against the cost of living. “Students and the middle-class Brazilians are also participating in the protests, which makes this a slightly unusual social movement,” Rifflart observed.¶ For the new middle class, the spending related to hosting the World Cup in 2014 is a hard pill to swallow. “They find it indecent to spend between 11 and 15 billion dollars to organise this sporting event, while public services and infrastructure need money,” the economist explained.¶ he government is therefore faced with middle-class citizens demanding public services that are up to the level of their new social status. “It’s the price Brazil is paying for the growth that allowed 30 million Brazilians to lift themselves out of poverty and join the middle class over the past several years,” said Stéphane Witkowski, chairman of the board at Paris’s Institute of Latin American Studies, in an interview with French daily Le Figaro.¶ Moreover, the quality of education available to most Brazilians remains “very weak”, noted Christine Rifflart, while the best schools are still largely attended by those who can pay for them: the richest Brazilians. Brazil Economy is diverse-Ag not key Brazil Sourcing 6(BrazilSourcing.com 2006 “Manufacturing Base”, http://www.brazilsourcing.com/manufbase.php) Brazil has one of the most diverse industrial sectors in Latin America with industries of textiles, shoes, chemicals, cement, lumber, iron ore, tin, steel, aircraft, motor vehicles and parts, other machinery and equipment.¶ It exports transport equipment, iron ore, soybeans, footwear, coffee, autos and imports machinery, electrical and transport equipment, chemical products, oil, automotive parts, electronics. The main commercial partners of Brazil are the USA, Colombia, Germany, Japan, Argentina, China, Canada and United Kingdom.¶ CHIEF EXPORTS: Manufactures, iron ore, soybeans, footwear, coffee.¶ CHIEF IMPORTS: Machinery and equipment, chemical products, oil, electricity¶ Manufacturing¶ Major products in the manufacturing sector are televisions, VCRs, telephones, and computer chips. There are a few national companies that are domestically oriented, such as Consul and Brastemp. There are also companies that are primarily export oriented, such as Nokia, Intel, and Compaq.¶ State participation in manufacturing occurs in the production of textiles and clothing, footwear, food, and beverages. These industries comprise a large proportion of the manufacturing sector, but there are also new industries that have been developed in the last few decades with government aid. Machinery and transport equipment, construction materials, sugar cane and wood derivatives, and chemicals are important manufacturing industries. Direct government participation is noticed in the oil processing industry and passenger jet aircraft industry through partial ownership of such companies. Indirect government participation is noticed in the textile industry and machinery industry through export subsidies and low interest loans.¶ Transport Vehicles¶ Automobiles are the most important manufactured items in Brazil. Brazil's passenger automotive production was approximately 2.45 million passenger car units in 2005. Brazil has manufacturing plants for General Motors, Volkswagen, Ford, Fiat, Honda, and Toyota. Workers are highly unionized, receiving the highest salaries among the manufacturing industries¶ Textiles¶ The national textile industry is responsible for 3 percent of world production. Brazil has the largest textile operating facilities in Latin America. The textile industry is also labor intensive, employing 1.65 million people in 2006. Fibers and leather are used to produce clothing, shoes, and luggage. Brazilian shoes are exported mainly to Europe, where they are famous for their quality.¶ Paper¶ The Brazilian paper industry was responsible for the production of 8.8 million metric tons and the pulp industry produced 11 million metric tons in 2006. The industry consisted of approximately 200 companies, employing approximately 80,000 people directly in their processing operations and 60,000 people in forestry operations.¶ Mining¶ The mining sector was protected by the 1988 constitution against foreign majority participation of direct mining companies. This was a setback for the development of the mining sector because domestic investors lacked the capital for extensive mineral exploration. Private Brazilian investors and Brazilian corporations own the majority of the mineral industry. The participation of foreign capital is very limited due to Brazilian mining laws. However, in 1995 the Congress approved an amendment to the constitution allowing private companies (including foreigners) to participate in the mining industry through joint ventures, deregulating investments, and the privatization of stateowned mining plants. Shortly afterwards, the state-owned Companhia Vale do Rio Doce was privatized.¶ The country is the world's largest producer of bauxite, gemstones, columbium, gold, iron ore, kaolin, manganese, tantalum, and tin. Major exports are iron ore, tin, and aluminum. The states of Minas Gerais, Bahia, and Goiás, located in the midwest of Brazil, have deposits of diamonds and other precious and semiprecious stones.¶ Financial Services¶ The government owns most of the financial sector, the largest component of the services industry. The 3 largest banks of Brazil are the Bank of Brazil, Federal Economic Register, and National Bank of Economic and Social Development (BNDES).¶ The Bank of Brazil is the largest bank in Brazil and the largest financial institution in Latin America. It has 12.9 million customers and agencies in 30 different countries, employing 90,378 people.¶ The Brazilian Discount Bank (BRADESCO) and Itaú have the largest assets in the private sector.¶ Retail¶ This sector is responsible for the highest number of employed people in all sectors of the services industry. The bulk of employed people in this sector come from companies that employ less than 500 employees. Combined retail and wholesale sectors were made up of 708,635 retail and wholesale outlets. There are few retail chains in the economy. Most of them are located in the capitals of each state but are not part of the retail context in the less developed economies in rural areas. Food, grocery, and other retail chains are located in the coastal areas whereas small family-owned businesses compose the retail sector in smaller cities. The smaller retail businesses are responsible for employing a large number of people No timeframe – It would take 17 years to repay its carbon debt Fargione et al. ’08 (Joseph Fargione, Jason Hill, David Tilman, Stephen Polasky, and Peter Hawthorne, Writers for Science Mag, 2/7/8, “Clearing and Biofuel Debt”, http://www.sciencemag.org/content/319/5867/1235.full) Our results show that converting native ecosystems to biofuel production results in large carbon debts (Fig. 1A). We attribute 13, 61, and 17% of this carbon debt to coproducts for palm, soybeans, and corn, respectively (Fig. 1B) (5). The carbon debts attributed to biofuels (quantities of Fig. 1A multiplied by the proportions of Fig. 1B) would not be repaid by the annual carbon repayments from biofuel production (Fig. 1C and table S2) for decades or centuries (Fig. 1D). Converting lowland tropical rainforest in Indonesia and Malaysia to palm biodiesel would result in a biofuel carbon debt of ∼610 Mg of CO2 ha–1 that would take ∼86 years to repay (Fig. 1D). Until then, producing and using palm biodiesel from this land would cause greater GHG release than would refining and using an energy-equivalent amount of petroleum diesel. Converting tropical peatland rainforest to palm production incurs a similar biofuel carbon debt from vegetation, but the required drainage of peatland causes an additional sustained emission of ∼55 Mg of CO2 ha–1 yr–1 from oxidative peat decomposition (5) (87% attributed to biofuel; 13% to palm kernel oil and meal). After 50 years, the resulting biofuel carbon debt of ∼3000 Mg of CO2 ha–1 would require ∼420 years to repay. However, peatland of average depth (3 m) could release peat-derived CO2 for about 120 years (7, 13). Total net carbon released would be ∼6000 Mg of CO2 ha–1 over this longer time horizon, which would take over 840 years to repay. Soybean biodiesel produced on converted Amazonian rainforest with a biofuel carbon debt of >280 Mg of CO2 ha–1 would require ∼320 years to repay as compared with GHG emissions from petroleum diesel. The biofuel carbon debt from biofuels produced on converted Cerrado is repaid in the least amount of time of the scenarios that we examined. Sugarcane ethanol produced on Cerrado sensu stricto (including Cerrado aberto, Cerrado ∼17 years to repay the biofuel carbon debt. Soybean biodiesel from the drier, less productive grass-dominated end of the densu, and Cerradão), which is the wetter and more productive end of this woodland-savanna biome, would take Cerrado biome (Campo limpo and Campo sujo) would take ∼37 years. Ethanol from corn produced on newly converted U.S. central grasslands results in a biofuel carbon debt repayment time of ∼93 years.