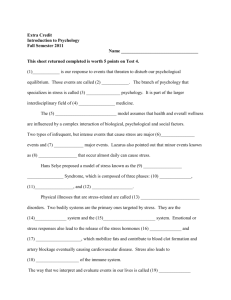

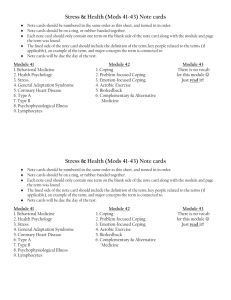

Stress - Slides

advertisement

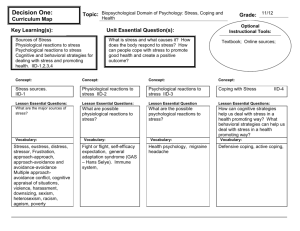

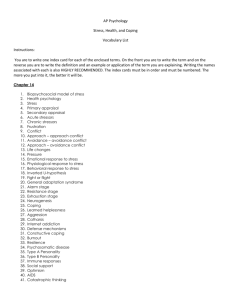

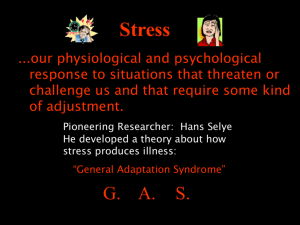

STRESS Three Views of Stress 1. Focus on the environment: stress as a stimulus (stressors) 2. Reaction to stress: stress as a response (distress) 3. Relationship between person and the environment: stress as an interaction (coping) Stressors Some examples? Stressors War Overcrowding Deadlines Dense traffic Marital conflict Work stress Acute vs. Chronic Stress Acute stress Sudden, typically short-lived, threatening event (e.g., robbery, giving a speech) Chronic stress Ongoing environmental demand (e.g., marital conflict, work stress, personality) Acute Stress Acute Stress – Rozanski 1988 Subjects – 39 individuals with coronary artery disease Stress tasks (0-5 minutes each): Mental arithmetic Stroop-colour word conflict task Stress speech (talk about personal fault) Graded exercise on bicycle (until chest pain or exhaustion) Acute Stress – Rozanski 1988 Outcome – stress response Myocardial ischemia determined by radionuclide ventriculography (measures wall motion abnormalities in the heart) Acute Stress – Rozanski 1988 Results Cardiac wall motion abnormalities were significantly greater with stress speech than other mental stress tasks (p < .05) and was of the same order of magnitude as that with graded exercise. Wall motion abnormalities occurred with lower heart rate during stress than during exercise (64 vs. 94 beats/min, p < .001) Chronic Stress – Frankenhauser, 1989 Subjects – 30 managerial and 30 clerical workers Equal number of men and women Outcome: blood pressure, heart rate, and catecholamines measured throughout workday and non-workday. Chronic Stress – Frankenhauser, 1989 No gender differences in the effect of work on BP and HR. In both men and women, BP and HR were higher on a workday than a non-workday. Chronic Stress – Frankenhauser, 1989 Catecholamine Response 3 2.5 2 Women Men 1.5 1 0.5 0 10:00 12:00 14:00 Time of Day 16:00 18:00 20:00 Three Views of Stress 1. Focus on the environment: stress as a stimulus (stressors) 2. Reaction to stress: stress as a response (distress) 3. Relationship between person and the environment: stress as an interaction (coping) Fight or Flight Response Increase in Epinephrine & norepinephrine Cortisol Heart rate & blood pressure Levels & mobilization of free fatty acids, cholesterol & triglycerides Platelet adhesiveness & aggregation Decrease in Blood flow to the kidneys, skin and gut Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome (1956, 1976, 1985) Perceived Stressor Alarm Reaction •Fight or flight Resistance •Arousal high as body tries defend and adapt. If stress continues …. Exhaustion •Limited physical resources; resistance to disease collapses; death Cognitive Model of Stress Lazarus & Folkman Potential stressor (external event) Primary appraisal – is this event positive, neutral or negative; and if negative, how bad? Secondary appraisal – do I have resources or skills to handle event? If No, then distress. Cognitive Model of Stress Lazarus & Folkman Primary appraisal – Is there a potential threat? Outcome – Is it irrelevant, good, or stressful? If stressful, evaluate further: Harm-loss – amount of damage already caused. Threat – expectation for future harm. Challenge – opportunity to achieve growth, etc Cognitive Model of Stress Lazarus & Folkman Secondary appraisal – Do I have the resources to deal effectively with this challenge or stressor? Cognitive Model of Stress Lazarus & Folkman High Threat Low Resources High Stress High Threat High Resources High Demands High/low demands Low Threat Low Resources Low demands Some stress Low Threat High Resources Low demands Low or no stress Moderate Stress Personal Factors Affecting Stress Appraisal Intellectual Motivational Personality Beliefs Situational Factors Affecting Stress Appraisals Strong demands Imminent Life transition Timing Ambiguity – role or harm ambiguity Desirability Controllability Behavioural control – perform an action Cognitive control – using a mental strategy Learned Helplessness – Seligman, Peterson, et al. Dogs exposed to unavoidable shocks Following exposure, when placed in a situation where they can now jump to avoid the shock, they fail to make the escape response. Learned helplessness occurs when one perceives that one’s actions (e.g., working hard) does not lead to the expected outcome (e.g., high grade). Job Strain – Karasek et al., 1981 Demands High High Control Low STRAIN Low Job Stress – other aspects Physical environment Poor interpersonal relationships Perceived inadequate recognition or advancement Unemployment (even anticipated) Role conflict High responsibility for others Biopsychosocial Aspect of Stress How stress affects health Via behaviour Via physiology Behavioural Aspects Increased alcohol Smoking Increased caffeine Poor diet Inattention leading to carelessness Physiological Aspects Cardiovascular reactivity – increased blood pressure, platelets, lipids (cholesterol) Endocrine reactivity – increased catecholamines and corticosteroids Immune reactivity – increased hormones impairs immune function Psychophysiological Disorders Digestive system – e.g., ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome Respiratory system – e.g., asthma Cardiovascular system – e.g., hypertension, lipid disorders, heart attack, angina Stress-Illness Relationship Illness Preexisting physiological or psychological vulnerability Physiological & psychological wear and tear Illness precursors, symptoms Exposure to stress Behavioural changes & Coping efforts Illness behaviour MODERATORS OF THE STRESS EXPERIENCE What is coping? Process of managing the discrepancy between the demands of the situation and the available resources. Ongoing process of appraisal and reappraisal (not static) Can alter the stress problem OR regulate the emotional response. Emotion-Focused Coping Aimed at controlling the emotional response to the stressor. Behavioural (use of drugs, alcohol, social support, distraction) and cognitive (change the meaning of the stress). Often used when the person feels he/she can’t change the stressor (e.g., bereavement); or Doesn’t have resources to deal with the demand. Problem-Focused Coping Aimed at reducing the demands of the situation or expanding the resources for dealing with it. Often used when the person believes that the demand is changeable. Coping responses – respond yes or no. Tried to see the positive side of it. Tried to step back from the situation and be more objective. 3. Prayed for guidance or strength. 4. Sometimes took it out on others when I felt angry and depressed. 5. Got busy with other things to keep my mind off the problem. 6. Read relevant material for solutions and considered several alternatives. 7. Took some action to improve the situation. 1. 2. Problem-Focused Coping Planful Problem-Solving – analyzing the situation to arrive at solutions and then taking direct action to correct the problem. Confrontive Coping – taking assertive action, often involving anger or risk taking to change the situation. Emotion-Focused Coping Seeking social support – can be either problem or emotion-focused coping. Distancing – cognitive effort to detach Escape-avoidance – wishful thinking or taking action to escape or avoid it. Self-control – attempting to modulate one’s feelings in response to the stressor. Accepting responsibility – acknowledging one’s role in the situation while trying to put things right. Positive reappraisal – create positive meaning. Cognitive Re-structuring Process by which stress-provoking thoughts are replaced with more constructive one. Gender and Coping Men generally employ problem-focused coping strategies more than emotional focused strategies. Opposite for women, with women more often employing emotion-focused strategies. If men and women in same occupation, gender differences disappear, suggesting that societal sex roles influence choice of coping strategies. Socio-economic Status (SES) and Coping People with higher SES tend to use problemfocused coping strategies more often (Billings & Moos, 1981). Why do people who have lower SES use problem-focus coping strategies less often than those with high SES? Personality or Coping Style Negative affectivity Pessimism – optimism Hardiness Life Orientation Test (Scheier & Carver) In uncertain times, I usually expect the best. If something can go wrong for me it will. I always look on the bright side. I’m always optimistic about my future. I hardly ever expect things to go my way. Things never work out the way I want them to. I’m a believer in the idea that “every cloud has a silver lining.” 8 I rarely count on good things happening to me. 9 Overall, I expect more good things to happen to me than bad. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Personality or Coping Style Negative affectivity Pessimism – optimism Hardiness Social Support Emotional support – expression of empathy, understanding, caring, etc. Esteem support – positive regard, encouragement, validating self-worth Tangible or instrumental – lending a helpful hand. Information support – providing information, new insights, advice. Network support – feeling of belonging Factors Influencing Utilization or Availability Social– people Support of Temperament differ in their needs for social support. Social support can be detrimental if you are the type of person who likes to handle things on your own. Previous experience with social support influences your likelihood of seeking out social support in the future. Threats to Social Support Stressful events can interfere with your ability to use social supports. People under stress may become so focused on talking about their problems that they drive their support systems away. Supports agents may react in a way that makes the problem worse. Support providers may be adversely effected by providing support. Alxheimer’s Disease (AD) – Effect on Caregivers Subsample of the Cardiovascular (CVD) Health Study, a prospective study of risk factors for CVD in the elderly. Excluded: disabled confined to wheel chair, unable to attend field centres, or undergoing cancer treatment. Caregivers defined as those whose spouse had difficulty with one activity of daily living due to physical or mental health problem. 392 caregivers and 427 non-caregivers recruited. AD – Effect on Caregivers Caregivers were asked to rate the degree of mental and physical strain associated with caregiving (3point response format). Sample subdivided into four groups: noncaregivers; spouse disabled but not helping him/her; caregiver but no reports of strain; and caregiver with reports of strain. Followed for 4.5 years (range 3.4 – 5.5 years). Main outcome – mortality (100% follow-up achieved). AD – Effect on Caregivers Results 81% of caregivers were providing care. 56% reported caregiver strain. Mortality – 9.4% in non-caregivers; 17.3% in ‘caregivers’ not providing care; 13.8% in nonstrained caregivers; and 17.3% in strained caregivers. Generally Social Support Associated with Good Effects Increase survival rates in women who have breast cancer. Lower blood pressure Decrease risk of mortality PSYCHOLOGICAL PREDICTORS OF SUDDEN CARDIAC DEATH IN CAMIAT J. Irvine, A. Basinski, B. Baker, S. Jandciu, M. Pickett, J. Cairns, S. Connolly, M. Gent, R. Roberts, & P. Dorian, Psychos Med 1999 Funded by Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario Psychosocial Predictors of Sudden Cardiac Death in CAMIAT Measures: Cook-Medley Index: measures of hostility, anger, cynicism Beck Depression Inventory Symptom Checklist-90: psychological distress Social Support: measures of social participation, network and perceived social support Psychosocial Predictors of Sudden Cardiac Death Variable Relative Risk 2.86 1.37 – 5.99 0.005 Hx CHF 3.86 1.89 – 7.89 0.001 Depress. – P 2.48 1.14 – 5.35 0.02 Depress. - A 0.52 0.15 – 1.76 0.29 Network Cont. 1.04 1.00 – 1.06 0.01 Social Activities 0.98 0.96 – 1.00 0.05 Previous MI 95% CI p STRESS MANAGEMENT Stress Management – teaches coping techniques Reduce harmful environmental conditions Teaches techniques by which person can develop stress tolerance. Helps client maintain a positive self-image. Help maintain emotional equilibrium. Help client maintain or develop satisfying relations with others. Cognitive Therapy – Albert Ellis, Aaron Beck Assumes that stress arises or is augmented by faulty or irrational ways of thinking. Catastrophizing – “It is awful if I get turned down when I ask for a date”. Overgeneralizing – “I didn’t get a good grade on this test. I can’t get anything right”. Selective abstraction – Only seeing specific details of the situation (e.g., Seeing the negatives but missing the positive details). Cognitive Therapy Often these irrational beliefs or faulty thinking errors stem from past “programming”. E.g., Not receiving adequate love and nurturance as a child may lead to feelings that loved ones in the present don’t “quite love you enough”. Hypothesis testing – client is encouraged to test out these irrational beliefs by collecting evidence for or against the belief. Cognitive Therapy Errors in Information Processing - Irrational Thinking Errors include: Emotional reasoning Overgeneralization Catastrophic thinking Mind reading Selective negative focus, etc. Relaxation Therapy Aims to either reduce hyperarousal or curb emotional-physiological reactivity. Progressive muscular relaxation Mental imagery Meditation Autogenic training Time Management Set short-term (e.g., daily) and long-term (e.g., yearly) goals. Make daily to-do lists (prioritize each). Make a daily schedule for when and where you will carry out your to-do list items (estimate time allocated for each to-do item). Revise throughout the day as needed.