Chapter 13

Digging Deeper

Contents:

|THE CASE OF THE DISAPPEARING DIVIDEND TAX | TAX TREATMENT OF CONSTRUCTIVE

DIVIDENDS | STOCK DIVIDENDS—§ 305 | STOCK RIGHTS |

DISPROPORTIONATE REDEMPTIONS AND COMPLETE TERMINATION REDEMPTIONS |

STOCK ATTRIBUTION RULES | LIQUIDATIONS—PARENT-SUBSIDIARY SITUATIONS |

THE CASE OF THE DISAPPEARING DIVIDEND TAX

1. U.S. banks and offshore hedge funds have developed a novel technique for avoiding the tax on

dividends entirely. The strategy involves the use of financial derivatives. A simple version of the

strategy is called a dividend swap. In the swap, a U.S. bank buys a block of stock from an

offshore hedge fund. The bank and the hedge fund also enter into a derivatives contract. The

contract requires the bank to make payments to the hedge fund equal to the total return on the

stock (both increases in fair market value and dividends) for a designated time period. These

payments equal the income and gain the stock would have provided to the hedge fund if it had

continued to own the stock. In exchange for these payments, the hedge fund

agrees to pay the bank an amount based on some benchmark interest rate. The hedge fund also

agrees that it will pay the bank an amount equal to the loss if the fair market value of the stock

declines.

After purchasing the stock from the hedge fund, the bank receives taxable dividend income. For

tax purposes, however, the dividend income is completely offset by the expense of payments

made to the hedge fund under the derivatives contract. In return, the bank receives compensation

from the hedge fund equal to a benchmark interest rate. The overseas hedge fund no longer

receives taxable dividend income, and the swap payments received are not subject to U.S.

taxation. As a result, taxable dividend income is converted to tax-free income.

Some experts estimate that the strategy has allowed hedge funds to avoid paying more than $1

billion a year in taxes on U.S. dividends.

TAX TREATMENT OF CONSTRUCTIVE DIVIDENDS

2. Global Tax Issues—Deemed Dividends from Controlled Foreign Corporations. U.S.

multinational companies often conduct business overseas using foreign subsidiaries. One might

think that these controlled foreign corporations (CFCs) would be ideal for income tax avoidance if

incorporated in a low-tax jurisdiction (a tax haven country). In the absence of any rules to the

contrary, the higher U.S. tax on foreign earnings could be deferred until the earnings are

repatriated to the United States through dividends paid to the U.S. parent.

To prevent this deferral, the tax law compels a U.S. parent corporation to recognize some of the

unrepatriated earnings of a CFC as income. The U.S. parent’s basis in the CFC stock is

increased by the amount of the taxed but unrepatriated earnings. Subsequently, when cash or

property is actually paid to the U.S. parent (i.e., when taxed earnings are repatriated), no income

results. Thus, the CFC rules preclude some deferral but do not lead to double taxation. See

Chapter 16 for more discussion of CFCs.

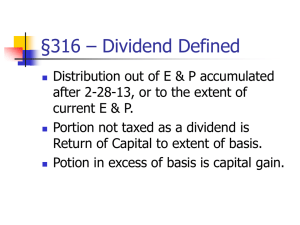

STOCK DIVIDENDS—§ 305

3. For each of the exceptions listed below, distributions of corporate stock may be taxed as

dividends.

Distributions payable in either stock or property, at the election of the shareholder.

Distributions of property to some shareholders, with a corresponding increase in the

proportionate interest of other shareholders in either assets or E & P of the distributing

corporation.

Distributions of preferred stock to some common shareholders and of common stock to

other common shareholders.

Distributions of either common or preferred stock to preferred-stock shareholders.

Distributions of convertible preferred stock, unless it can be shown that the distribution

does not result in a disproportionate distribution.

STOCK RIGHTS

4. The rules for determining the taxability of stock rights are identical to those for determining the

taxability of stock dividends. If the rights are taxable, the recipient recognizes gross income to the

extent of the fair market value of the rights. The fair market value then becomes the shareholderdistributee's basis in the rights.1 If the rights are exercised, the holding period for the new stock

begins on the date the rights (whether taxable or nontaxable) are exercised. The basis of the new

stock is the basis of the rights plus the amount of any other consideration given.

If the stock rights are not taxable and the value of the rights is less than 15 percent of the value of

the old stock, the basis of the rights is zero. However, the shareholder may elect to have some of

the basis in the formerly held stock allocated to the rights.2 The election is made by attaching a

statement to the shareholder's return for the year in which the rights are received. 3 If the fair

market value of the rights is 15 percent or more of the value of the old stock and the rights are

exercised or sold, the shareholder must allocate some of the basis in the formerly held stock to

the rights.

Example: A corporation with common stock outstanding declares a nontaxable dividend payable

in rights to subscribe to common stock. Each right entitles the holder to purchase one share of

stock for $90. One right is issued for every two shares of stock owned. Fred owns 400 shares of

stock purchased two years ago for $15,000. At the time of the distribution of the rights, the market

value of the common stock is $100 per share, and the market value of the rights is $8 per right.

Fred receives 200 rights. He exercises 100 rights and sells the remaining 100 rights three months

later for $9 per right.

Fred need not allocate the cost of the original stock to the rights because the value of the rights is

less than 15% of the value of the stock ($1,600/$4,000 = 4%). If Fred does not allocate his

original stock basis to the rights, the tax consequences are as follows.

Basis in the new stock is $9,000 ($90 exercise price 100 shares). The holding period of

the new stock begins on the date the stock was purchased.

Sale of the rights produces long-term capital gain of $900 ($9 sales price 100 rights).

The holding period of the rights starts with the date the original 400 shares of stock were

acquired.

If Fred elects to allocate basis to the rights, the tax consequences are as follows.

Basis in the stock is $14,423 ($40,000 value of stock/$41,600 value of rights and stock

$15,000 cost of stock).

Basis in rights is $577 ($1,600 value of rights/$41,600 value of rights and stock $15,000

cost of stock).

When Fred exercises the rights, his basis in the new stock will be $9,288.50 ($9,000 cost

+ $288.50 basis in 100 rights).

Sale of the rights would produce a long-term capital gain of $611.50 ($900 sales price –

$288.50 basis in the remaining 100 rights).

DISPROPORTIONATE REDEMPTIONS AND COMPLETE TERMINATION REDEMPTIONS

5. Disproportionate Redemptions. A redemption of stock qualifies for sale or exchange

treatment under § 302(b)(2) as a disproportionate redemption if two conditions are met.

After the distribution, the shareholder owns less than 80 percent of the interest owned in

the corporation before the redemption. For example, if a shareholder owns a 60 percent

interest in a corporation that redeems part of the stock, the shareholder’s percentage of

ownership after the redemption must be less than 48 percent (80 percent of 60 percent).

After the distribution, the shareholder owns less than 50 percent of the total combined

voting power of all classes of stock entitled to vote.

In determining a shareholder’s percentage of ownership before and after a redemption, the stock

attribution rules apply.

Example: Bob, Carl, and Dan, unrelated individuals, own 30 shares, 30 shares, and 40 shares,

respectively, in Wren Corporation. Wren has 100 shares of stock outstanding and E & P of

$200,000. The corporation redeems 20 shares of Dan’s stock for $30,000. Dan paid $200 a share

for the stock two years ago. Dan’s ownership in Wren before and after the redemption is as

follows.

Dan's

Ownership

Total Shares Ownership Percentages

Before redemption

After redemption

100

40

40% (40/100)

80

20

25% (20/80)*

80% of Original

Ownership

32% (80% 40%)

*The denominator of the fraction is reduced after the redemption (from 100 to 80).

Dan’s 25% ownership after the redemption meets both tests of § 302(b)(2). It is less than 80% of

his original ownership and less than 50% of the total voting power. The distribution qualifies as a

stock redemption that receives sale or exchange treatment. Therefore, Dan has a long-term

capital gain of $26,000 [$30,000 - $4,000 (20 shares $200)].

Assume instead that Carl and Dan are father and son. The redemption described previously

would not qualify for sale or exchange treatment because of the effect of the stock attribution

rules. Dan is deemed to own Carl’s stock before and after the redemption. Dan’s ownership in

Wren before and after the redemption is as follows.

Dan's

Dan's Direct and

80% of

Total

Direct

Carl’s

Indirect

Ownership

Original

Shares Ownership Ownership

Ownership

Percentages Ownership

Before

redemption

100

40

30

70

70% (70/100)

After

redemption

80

20

30

50

62.5%

(50/80)

56%

(80%/70%)

Dan's direct and indirect ownership of 62.5% fails to meet either of the tests of § 302(b)(2). After

the redemption, Dan owns more than 80% of his original ownership and more than 50% of the

voting stock. Thus, the redemption does not qualify for sale or exchange treatment and results in

a dividend distribution of $30,000 to Dan.

Complete Termination Redemptions. If a shareholder terminates his or her entire stock

ownership in a corporation through a stock redemption, the redemption qualifies for sale or

exchange treatment. The attribution rules generally apply in determining whether the

shareholder's stock ownership has been terminated. However, the family attribution rules do not

apply to a complete termination redemption if both of the following conditions are met.

The former shareholder does not hold or acquire any economic interest, other than that

of a creditor, in the corporation after the redemption (including an interest as an officer, a

director, or an employee) for at least 10 years.

The former shareholder files an agreement to notify the IRS of any prohibited interest

within the 10-year post-redemption period and to retain all necessary records pertaining

to the redemption during this time period.

A shareholder can reacquire an interest in the corporation by bequest or inheritance, but in no

other manner. The required agreement should be in the form of a separate statement signed by

the shareholder and attached to the return for the year in which the redemption occurs. The

agreement should state that the shareholder agrees to notify the IRS within 30 days of

reacquiring a prohibited interest in the corporation within the 10-year period following the

redemption.4

Example: Kevin owns 50% of the stock in Green Corporation, while the remaining interest in

Green is held as follows: 40% by Wilma (Kevin's wife) and 10% by Carmen (a key employee).

Green redeems all of Kevin's stock for its fair market value. As a result, Wilma and Carmen are

the only remaining shareholders, now owning 80% and 20%, respectively. If the two requirements

for the family attribution waiver are met, the transaction qualifies as a complete termination

redemption and results in sale or exchange treatment. If the waiver requirements are not

satisfied, Kevin is deemed to own Wilma's (his wife's) stock, and the entire distribution is taxed as

a dividend (assuming adequate E & P).

If Kevin qualifies for the family attribution waiver for the redemption, he treats the transaction as a

sale or exchange. However, if he purchases Carmen's stock seven years after the redemption, he

has acquired a prohibited interest, and the redemption is reclassified as a dividend. Kevin must

notify the IRS and will owe additional taxes due to this revised treatment.

Summary of the Qualifying Stock Redemption Rules

Type of Redemption

Not essentially equivalent to a

dividend [§ 302(b)(1)]

Requirements to Qualify

Meaningful reduction in shareholder’s voting interest.

Reduction in shareholder’s right to share in earnings or

in assets upon liquidation also considered.

Stock attribution rules apply.

Substantially disproportionate

[§ 302(b)(2)]

Shareholder’s interest in the corporation, after the

redemption, must be less than 80% of interest before the

redemption and less than 50% of total combined voting

power of all classes of stock entitled to vote.

Stock attribution rules apply.

Complete termination [§ 302(b)(3)]

Entire stock ownership terminated.

In general, stock attribution rules apply. However, family

attribution rules may be waived. Former shareholder

must have no interest, other than as a creditor, in the

corporation for at least 10 years and must file an

agreement to notify IRS of any prohibited interest

acquired during 10-year period. Shareholder must retain

all necessary records during 10-year period.

Partial liquidation [§ 302(b)(4)]

Not essentially equivalent to a dividend.

Genuine contraction of corporation’s business.

Termination of an active business.

Corporation has two or more qualified trades or

businesses.

Corporation terminates one qualified trade or

business while continuing another.

Contracted business was not acquired in a taxable

transaction within five years.

Distribution may be in form of cash or property.

Redemption may be pro rata.

Stock attribution rules do not apply.

Redemption to pay death taxes

[§ 303]

Value of stock of one corporation in gross estate exceeds

35% of value of adjusted gross estate.

Stock of two or more corporations treated as stock of a

single corporation in applying the 35% test if decedent

held a 20% or more interest in the stock of each of the

corporations.

Redemption limited to sum of death taxes and funeral and

administration expenses.

Generally tax-free because tax basis of stock is FMV on

date of decedent’s death and value is unchanged at

redemption.

Stock attribution rules do not apply.

STOCK ATTRIBUTION RULES

6. A stock redemption that qualifies for sale or exchange treatment generally must result in a

substantial reduction in a shareholder’s ownership in the corporation. If this does not occur,

proceeds received for a redemption of the shareholder’s stock are taxed as ordinary dividend

income. In determining whether a shareholder’s interest has substantially decreased, the stock

owned by certain related parties is attributed to the shareholder whose stock is redeemed. 5

Thus, the stock attribution rules must be considered along with the stock redemption provisions.

Under these rules, related parties include the following family members: spouses, children,

grandchildren, and parents. Attribution also takes place from and to partnerships, estates, trusts,

and corporations (50 percent or more ownership required in the case of corporations). The exhibit

below summarizes the stock attribution rules.

Deemed or Constructive Ownership

Family

Partnership

An individual is deemed to own the stock owned by his or

her spouse, children, grandchildren, and parents (not

siblings or grandparents).

A partner is deemed to own the stock owned by a

partnership to the extent of the partner's proportionate

share in the partnership.

Stock owned by a partner is deemed to be owned in full by

a partnership.

Estate or

trust

A beneficiary or an heir is deemed to own the stock owned

by an estate or a trust to the extent of the beneficiary's or

heir's proportionate interest in the estate or trust.

Stock owned by a beneficiary or an heir is deemed to be

owned in full by an estate or a trust.

Corporation

Stock owned by a corporation is deemed to be owned

proportionately by any shareholder owning 50% or more of

the corporation's stock.

All stock owned by a shareholder who owns 50% or more

of a corporation is deemed to be owned by the corporation.

Example: Larry owns 30% of the stock in Blue Corporation, the other 70% being held by his

children. For purposes of the stock attribution rules, Larry is treated as owning 100% of the Blue

stock. He owns 30% directly and, because of the family attribution rules, 70% indirectly.

Example: Chris owns 50% of the stock in Gray Corporation. The other 50% is owned by a

partnership in which Chris has a 20% interest. Chris is deemed to own 60% of Gray: 50% directly

and, because of the partnership interest, 10% indirectly.

LIQUIDATIONS—PARENT–SUBSIDIARY SITUATIONS

7. Section 332, an exception to the general rule of § 331, provides that a parent corporation does

not recognize gain or loss on a liquidation of a subsidiary. In addition, the subsidiary corporation

recognizes neither gain nor loss on distributions of property to its parent.6

The requirements for applying § 332 are as follows.

The parent must own at least 80 percent of the voting stock of the subsidiary and at least

80 percent of the value of the subsidiary’s stock.

The subsidiary must distribute all of its property in complete cancellation of all of its stock

within the taxable year or within three years from the close of the tax year in which the

first distribution occurred.

The subsidiary must be solvent.7

If these requirements are met, nonrecognition of gains and losses becomes mandatory. However,

if the subsidiary is insolvent, the parent corporation will have an ordinary loss deduction.

Basis of Property Received by the Parent Corporation. Property received in the complete

liquidation of a subsidiary has the same basis it had in the hands of the subsidiary.8 This

carryover basis in the assets may differ significantly from the parent’s basis in the stock of the

subsidiary. Because the liquidation is a nontaxable exchange, the parent’s gain or loss on the

difference in basis is not recognized. Further, the parent’s basis in the stock of the subsidiary

disappears.

Example: Lark Corporation has a basis of $200,000 in the stock of Heron Corporation, a

subsidiary in which it owns 85% of all classes of stock. Lark purchased the Heron stock 10 years

ago. In the current year, Lark liquidates Heron Corporation and acquires assets that are worth

$800,000 and have a tax basis to Heron of $500,000. Lark Corporation takes a basis of $500,000

in the assets, with a potential gain upon their sale of $300,000. Lark’s $200,000 basis in Heron’s

stock disappears.

Example: Indigo Corporation has a basis of $600,000 in the stock of Kackie Corporation, a

wholly owned subsidiary acquired 10 years ago. It liquidates Kackie Corporation and receives

assets that are worth $400,000 and have a tax basis to Kackie of $300,000. Indigo Corporation

takes a basis of $300,000 in the assets it acquires from Kackie. If Indigo sells the assets, it has a

gain of $100,000 even though its basis in the Kackie stock was $600,000. Indigo’s loss on its

stock investment in Kackie will never be recognized.

In addition to the parent corporation taking the subsidiary’s basis in its assets, the parent’s

holding period for the assets includes that of the subsidiary. Further, the parent acquires other tax

attributes of the subsidiary, including the subsidiary’s net operating loss carryover, business credit

carryover, capital loss carryover, and E & P.

Summary of Liquidation Rules

Effect on the Shareholder

Basis of Property Received

Effect on the Corporation

§ 331—The general rule

provides for gain or loss

treatment on the difference

between the FMV of property

received and the basis of the

stock in the corporation. Gain

allocable to installment notes

received can be deferred to

point of collection.

§ 334(a)—Basis of assets

received by the shareholder

will be the FMV on the date of

distribution (except for

installment obligations on

which gain is deferred to the

point of collection).

§ 336—Gain or loss is

recognized for distributions in

kind and for sales by the

liquidating corporation.

Losses are not recognized for

distributions to related parties

if the distribution is not pro

rata or if disqualified property

is distributed. Losses may be

disallowed on sales and

distributions of built-in loss

property even if made to

unrelated parties.

§ 332—In liquidation of a

subsidiary, no gain or loss is

recognized to the parent.

Subsidiary must distribute all

of its property within the

taxable year or within three

years from the close of the

taxable year in which the first

distribution occurs. Minority

shareholders taxed under

general rule of § 331.

§ 334(b)(1)—Property has the

same basis as it had in the

hands of the subsidiary.

Parent’s basis in the stock

disappears. Carryover rules of

§ 381 apply. Minority

shareholders get FMV basis

under § 334(a).

§ 337—No gain or loss is

recognized to the subsidiary

on distributions to the parent.

Gain (but not loss) is

recognized on distributions to

minority shareholders.

Notes:

1

Reg. § 1.305-1(b).

2

§ 307(b)(1).

3

Reg. § 1.307-2.

4

Reg. § 1.302-4(a)(1).

5

§ 318.

6

§ 337(a).

7

§ 332(b) and Reg. §§ 1.332-2(a) and (b).

8

§ 334(b)(1) and Reg. § 1.334-1(b). But see § 334(b)(1)(B) (exception for property acquired in

some liquidations of foreign subsidiaries).

© 2015 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or

posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.