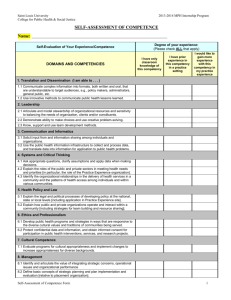

View/Open - Sacramento - The California State University

advertisement