Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism

advertisement

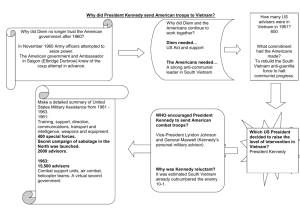

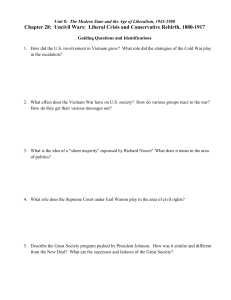

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Expanding the Liberal State – John Kennedy Third of the four televised 1960 debates Senator from Massachusetts: John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917-1963) was the son of wealthy businessman and controversial former ambassador to the U.K., Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. (1888-1969). He was elected senator to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1946, and then as U.S. Senator in 1952. In 1956, he was nominated as Vice President at the Democratic Convention, but came in second. The 1960 Campaign: Kennedy’s charisma, confidence, and good looks helped him gain an edge of Nixon in the four televised debates in Sept. and Oct. of 1960. He overcame concerns about his age (he was just 43) and his Catholicism. 2 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism 3 The Election of 1960 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Expanding the Liberal State – John Kennedy Kennedy Elected: Kennedy won by a small margin. He took 49.7 percent of the popular vote to Nixon’s 49.6, and 303 electoral votes to Nixon’s 219. There is still considerable debate about the role of questionable practices of Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s Democratic machine in delivering Illinois’s crucial electoral votes. The “New Frontier”: Kennedy put forth a set of domestic frontiers described as the “New Frontier,” but a coalition of Republicans and conservative Democrats frustrated several elements: his attempt to get legislation to provide federal funds for primary and secondary education and his Medicare program to provide health insurance for older Americans failed to get support in Congress. Other elements were successful: the expansion of unemployment protections, increases in Social Security payments, and federal funding for housing and slum clearance. 4 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Expanding the Liberal State – John Kennedy Kennedy Assassinated: On Nov. 22, 1963 during a visit to Dallas for a series of political appearances, Kennedy was assassinated by an embittered Marxist Lee Harvey Oswald (1939-1963). Oswald was a former Marine, trained as a radar operator. He had also defected to the Soviet Union in 1959, but returned in March 1961 with little notice. When he was about to be transferred from Dallas Police Headquarters on Nov. 24 to the county jail, he was shot be Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby (1911-1967). Warren Commission: The commission that investigated the assassination led by Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren (18911974) concluded in its September 1964 report that both Oswald and Ruby had not been involved in a conspiracy and that both acted alone. Many Americans still question this conclusion, and controversy surrounds the assassination to this day. 5 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism 6 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Expanding the Liberal State – Lyndon Johnson Lyndon Baines Johnson (1908-1973): A native of the poor hill country of west Texas, he had risen to become the majority leader of the U.S. Senate by 1955. He had first been elected to the House of Representatives in 1937, and then to the Senate in 1949. Failing to win the nomination in 1960, he surprised many by accepting the Vice Presidential slot on the Kennedy ticket. He easily beat conservative Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964, winning 61.1 percent of the popular vote and 486 electoral votes. “Great Society”: Johnson had been a masterful legislator, and firmly believed in the use of government power to better people’s lives. Between 1963 and 1966, LBJ garnered the most effective legislative record of any president since FDR. He was aided by a wave of emotional support after Kennedy’s assassination. He passed many “New Frontier” programs, but also created his own remarkable array of social reforms known as the “Great Society.” 7 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Expanding the Liberal State – The Assault on Poverty Medicare and Medicaid: LBJ created the first new federal social welfare programs since the New Deal, the most important of which was Medicare, which was passed in 1965 and provided federal funds to aid the elderly in paying medical expenses. In 1966, he passed Medicaid, which extended similar coverage to welfare recipients and indigent people of all ages. Failure of the OEO: The centerpiece of Johnson’s “War on Poverty” was the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), created in 1964. It offered an array of new educational, employment, housing, and healthcare programs (“Head Start” and “Job Corps” are examples). It was controversial because of its “Community Action” element, which allowed for members of poor communities participate in the planning and implementation of the programs meant to help them. The OEO spent nearly $3 billion in its first three years, but became a target of criticism for excesses and administrative failures of some of the programs it administered, and received less funding, especially as the war in Southeast Asia escalated (it was abolished in 1981). 8 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Expanding the Liberal State – Cities, Schools, and Immigration Robert C. Weaver Urban Issues: The Housing Act of 1961 provided $4.9 billion in federal grants for the preservation of open space, the development of mass-transit, and subsidies for middle-class housing. In 1966, LBJ created a new cabinet agency, the Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, and appointed the first black cabinet official, Robert C. Weaver (1907-1997). Federal Aid to Education: The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 provided federal funds for both public and parochial schools based on student need, not the needs of the schools themselves. Immigration Act of 1965: LBJ supported this law that limited immigration to 170,000 each year, but abolished the quota framework of the National Origins Act of 1924 that favored northern Europeans. By the 1970s, it transformed the American, with many more Asians coming to the United States than previously. 9 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The “Johnson Treatment”: Johnson literally “got into someone’s face” when in conversation, using his physical size to convey his dominance. Left: With Senator Richard B. Russell in 1963; Right: With new Supreme Court Associate Justice nominee Abe Fortas in 1968 10 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Expanding the Liberal State – Legacies of the Great Society Federal Spending: The Great Society reforms greatly increased federal spending, and even though LBJ passed a 1964 tax cut of $11.5 billion, economic growth made up for much of the revenue lost. But as the programs expanded and military spending grew with the American presence in Vietnam expanding, the deficit began to outpace revenue. The federal budget in 1961 had been $94.4 billion, but by 1970 it had risen to $196.6 billion (in 2012, it was 2.627 trillion). Achievements of the Great Society: The failures of the Great Society later would feed disillusionment about the use of federal programs to solve social problems, but it nonetheless did have a significant impact: it reduced hunger, it made health care available to the elderly and poor, and reduced the number of American living below the poverty line from 21 percent in 1959 to 12 percent in 1969. 11 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – Expanding Protests: 1960-1961 JFK’s Wavering: When Kennedy took office in 1961, he was sympathetic to the civil rights movement, but was not proactive since he was afraid of alienating the power Southern Democrats in Congress. Pressure from African Americans: Throughout the 1950s, urban blacks in the North grew increasingly active in opposing discrimination in housing, jobs, and education. By 1960, this activism was growing in the South. Greensboro: In this North Carolina city in Feb. 1960, black college students organized a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter at a Woolworth’s store. Soon, such protests were spreading across the South, putting pressure on many merchants to integrate their facilities. 12 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – Expanding Protests: 1960-1961 SNCC: Some of the students who had participated in the sit-in protests formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the fall of 1960, a student branch of Dr. Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). “Freedom Rides”: In 1961, members of the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) and SNCC members organized “freedom rides” in bus trips throughout the South, forcing the desegregation of bus stations. They met with arrests and such savage violence (one bus was even firebombed) that U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy eventually cut a deal with governors would allow the National Guard and state police to protect the riders from mob violence, but would allow for local authorities to arrest them when they tried to use segregated facilities. 13 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Greensboro Sit-In Greyhound bus burning near Anniston, Alabama, in May 1960 Arrested freedom riders 14 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Medgar Evers The Battle for Racial Equality – Expanding Protests: 1963 Birmingham Demonstrations: In April 1963, Martin Luther King launched a series of nonviolent protests in Birmingham, Alabama, that were met with brutal force orchestrated by Police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor. In full view of television cameras, Connor’s officers used attack dogs, tear gas, and fire hoses on protesters, some of whom were small children. George C. Wallace (1919-1998): On June 11, 1963, the governor of Alabama blocked the doorway of a building at the University of Alabama to prevent two black students from enrolling, but was forced aside by federal marshals and U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach. Medgar W. Evers (1925-1963): On the same night as the Wallace standoff and a nationally televised civil rights speech by President Kennedy, prominent NAACP official Medgar Evers was shot and killed in his own driveway in Jackson, Mississippi. 15 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Birmingham, Alabama – May 1963 16 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – A National Commitment 17 Kennedy’s Speech: On June 11, 1963, Kennedy’s televised speech called civil rights a “moral issue facing the country.” Days later, he introduced legislation prohibiting segregation in “public accommodations,” discrimination in employment, and giving the federal government more power to pursue suits on behalf of school integration. March on Washington: On Aug. 28, 1963, over 200,000 demonstrators marched down the Washington Mall and gathered before the Lincoln Memorial for the largest civil rights protests in the nation’s history up to that point. MLK gave one of the greatest speeches of his career framed by the powerful phrase, “I have a dream…” Effect of the Kennedy Assassination: Three months later, President Kennedy’s death added a new impetus to the legislation he proposed, which had been stalled in the Senate after passing the House. LBJ using his considerable powers of persuasion, put a two-thirds majority together in the Senate to get the most important civil rights bill since Reconstruction passed in June 1964. Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism 18 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism LBJ presenting MLK with the pen he had just used to sign the Civil Rights Act of 1964 19 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – The Battle for Voting Rights “Freedom Summer”: In the summer of 1964, thousands of black and white civil rights workers spread across the South, but especially Mississippi, to register African American to vote in a campaign known as “Freedom Summer. Workers were met with violence, including three of the first to arrive—two whites, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, and one African America, James Chaney, were murdered with the complicity of local law enforcement. MFDP: The Freedom Summer also created the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) led by Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977) and others challenged the regular Mississippi Democratic Party’s seating at the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City, but were rebuffed. Selma Protests: MLK helped to organize a major demonstration in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965 to press for the black right to vote. Sheriff Jim Clark led the brutal attack on demonstrators, which was televised nationally. 20 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, March 7, 1965, in which peaceful demonstrators crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge were savagely beaten by police. Those attacked included SNCC organizer and future Georgia congressman, John Lewis. 21 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – The Battle for Voting Rights Voting Rights Act Approved: The events in Alabama helped LBJ gather enough momentum to pass the Civil Rights Acts of 1965, better known as the Voting Rights Act, which gave federal protection to African Americans trying to exercise their right to vote. – The Changing Movement Urban Black Communities: By 1966, 60 percent of all blacks lived in a metropolitan area and 45 percent lived outside of the South. While economic conditions appeared to be improving for most Americans, conditions for poor urban blacks seemed to be getting worse. 22 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – The Changing Movement “Affirmative Action”: While northern cities did not have Jim Crow laws, there was considerable employment discrimination against blacks. Many argued that the problem needed to be addressed by employers to be actively recruiting blacks. LBJ in 1965 gave his approval to the idea of “affirmative action.” Through an executive order signed in September that prohibited federal contractors or federally assisted ones “from discriminating in employment decisions on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” This idea marked the movement shift in focus from legal equality to economic equality. MLK’s Chicago Campaign: In summer 1966, MLK organized a campaign in Chicago to draw attention to housing and employment discrimination in northern cities. But the campaign met with considerable resistance from white residents, and failed to draw the attention that the Southern campaigns did. 23 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – Urban Violence The Riots: The problem of urban poverty had come to the fore before the 1966 Chicago campaign in the form of riots in African American neighborhoods in major cities. A few scattered disturbances happened in the summer of 1964, most notably in Harlem. The biggest since World War II happened in the Watts section of L.A. in August 1965, which was triggered by a white cop striking a bystander witnessing a traffic arrest, sparking a week of violence that killed twenty-four people and was quelled by the National Guard. In the summer of 1966, forty-three outbreaks occurred, while in the summer of 1967, eight major disorders took place, the worst being in Chicago and Cleveland. Televised images alarmed millions of Americans and added to a growing sense of doubt among some about the embracing of racial equality juts a few years before. 24 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Images from the 1965 Watts Riot in Los Angeles 25 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – Black Power Disillusionment: Many blacks became disappointed with the slow pace of change through cooperation with whites, so they increasingly turned toward the philosophy of “black power.” Racial Distinctiveness Emphasized: The ideology had many meanings, but in its essence, it meant a shift away from assimilation and an emphasis on racial distinctiveness and pride. Division: Groups that had emphasized cooperation with sympathetic whites—like the NAACP and King’s SCLC—now found competition from more radical groups. CORE and SNCC—which had started as moderate groups—now demanded more radical action and openly rejected the methods of older black leaders. 26 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – Black Power Radical Black Power: The most radical expression of black power came from the revolutionary Black Panther organization, and the Nation of Islam, which labeled whites as “devils” and encouraged blacks to embrace the organization’s form of Islam and embrace complete racial separation. Black Panthers: Huey P. Newton (1942-1989) and Bobby Seale (1936-) cofounded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966 in Oakland, California, initially to protect African Americans from police brutality. Malcolm X (1925-1965): The most celebrated member of the Nation of Islam was Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little; the “X” denoted his lost African surname). He rose to fame as a leader and spokesperson for the controversial group, but broke with it after a dispute with its leader, Elijah Muhammad, in March 1964. He then became a Sunni Muslim and disavowed his anti-white racism. In February 1965, he was assassinated by three members of the Nation of Islam. 27 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Battle for Racial Equality – Black Power 28 Huey P. Newton of the Black Panthers Malcolm X Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Black Panthers’ Ten-Point Plan (1966) 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) 9) 10) 29 We Want Freedom. We Want Power to Determine the Destiny of Our Black Community. We Want Full Employment for Our People. We Want an End to the Robbery by the Capitalists of Our Black Community. We Want Decent Housing Fit for the Shelter of Human Beings. We Want Education for Our People that Exposes the True Nature of this Decadent American Society. We Want Education that Teaches Us Our True History and Our Role in The Present-Day Society. We Want All Black Men to Be Exempt from Military Service. We Want an Immediate End to Police Brutality and Murder of Black People. We Want Freedom for All Black Men Held in Federal, State, County and City Prisons and Jails. We Want All Black People When Brought to Trial to Be Tried in Court by a Jury of Their Peer Group or People From Their Black Communities, as Defined by the Constitution Of the United States. We Want Land, Bread, Housing, Education, Clothing, Justice and Peace. Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism “Flexible Response” and the Cold War – Diversifying Foreign Policy Flexible Response: The Kennedy administration believed that the U.S. needed more military flexibility in responding to communism than the mostly nuclear-weapon-based approach of the Eisenhower administration, especially in the Third World, where the threat of communism appeared most imminent. He approved the expansion of the Special Forces trained to fight in a guerilla capacity in limited wars. “Alliance for Progress”: To fix the deteriorating relations with Latin America countries, JFK proposed a series of programs to aid economic development in the region Between 1962 and 1967 the U.S. supplied $1.4 billion per year to Latin America. Foreign Aid: In 1961, Kennedy created the Peace Corps in March, and the Agency for International Development (AID) in November 1961to coordinate foreign aid. 30 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism “Flexible Response” and the Cold War – Diversifying Foreign Policy Bay of Pigs: The Eisenhower administration had started an initiative to have the CIA train a paramilitary group of 2,000 anti-Castro Cubans to invade Cuba and start a counter-revolution. On April 17, 1961, the force landed and was quickly overwhelmed by well armed pro-Castro soldiers. The force had been expecting U.S. air support and a popular uprising to support them. Neither ever came, and the U.S. was left with an embarrassing black eye. – Confrontations with the Soviet Union Berlin Wall: Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971) and JFK met under tense conditions in Vienna in June 1961 and Khrushchev intimated war if the Allies did not pull out of West Berlin, partly because so many people from the East were fleeing to the West through the easily traversed border in central Berlin. At dawn on Aug. 13, 1961, the East German authorities began construction a wall to staunch the flow, and then shot anyone trying to cross. 31 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism “Flexible Response” and the Cold War – Confrontations with the Soviet Union Cuban Missile Crisis: In the summer of 1962, American intelligence officials observed the arrival of a new wave of Soviet technicians and equipment in Cuba. On Oct. 14, aerial spy plane photographs supplied incontrovertible evidence that the Soviets were building sites from which offensive nuclear missiles could be launched. On Oct. 22, JFK ordered a naval and air blockade of the island. Khrushchev Backs Down: On Oct. 26, JFK received a call from Khrushchev intimating that he would be willing to remove the missiles in exchange for an American pledge not to invade Cuba and if the U.S. removed middle-ranged missiles from Turkey. The ensuing thaw in relations led to the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. 32 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Captured anti-Castro rebels after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 Soviet freighter Anosov carrying missiles back to the U.S.S.R. after the Soviets agreed to remove the missiles from Cuba in Nov. 1962 Construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 33 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism “Flexible Response” and the Cold War – Johnson and the World Johnson’s Inexperience: While a masterful domestic politician, LBJ had little experience with foreign affairs. Intervention in the Dominican Republic: The repressive dictator of the Dominican Republic, Gen. Rafael Trujillo (1891-1961), was assassinated in 1961, toppling his government. For four years, various factions struggled for power. When a conservative faction began to lose power in 1965 to a left-wing nationalist coalition, LBJ sent in 30,000 U.S. troops to make sure a pro-Castro regime would not take power. 34 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The United States in Latin America, 1954-2001 35 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Agony of Vietnam – America and Diem 1955 cover of Time featuring Diem A Small War? The conflict in Vietnam at first seemed to be one of many Third World struggles on the periphery of the Cold War. Growing Support for Diem: After the Geneva Accords and French withdrawal in 1954, the U.S. threw its support behind South Vietnam’s new president, Ngo Dinh Diem (1901-1963). This aristocratic Catholic from central Vietnam at first had success pacifying some powerful religious sects and the South Vietnamese mafia, both with the help of the CIA. The U.S. started pouring in funds to support him, which it saw as an alternative to Ho Chi Minh. Campaign against Ho Chi Minh Supporters: In 1959, Diem started a campaign to eliminate supporters of Ho Chi Minh in the South, the Vietminh, who had stayed in the south after partition. Diem expanded this campaign into an attempt to reunify the country under his role. In response, the Vietminh created the National Liberation Front (NLF—known in the U.S. as the Viet Cong) to wage guerilla war against Diem in the south starting in 1960. 36 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Agony of Vietnam – America and Diem Diem Losing Support: By 1961, the NLF had won considerable support in the countryside of the South, and Diem was losing support of many groups in the South, including his own military. In 1963, Diem tried to repress Buddhism in an effort to make Catholicism the country’s dominant religion, sparking huge anti-government demonstrations. Some Buddhist monks doused themselves with gasoline and set themselves aflame, including Thic Quang Duc (1897-1963), whose image was disseminated worldwide. Diem Assassinated: In Fall 1963, JFK gave his approval for a coup against Diem’s tottering regime by a group of South Vietnamese generals. What was not desired by the U.S. was Diem’s assassination, as well as that of his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu. Over the next three years, the generals established as series of governments that were even less table than Diem’s. 37 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Marines landing at Civil Rights, Vietnam, Danang, 1965 and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Agony of Vietnam – From Aid to Intervention Johnson in Late 1963: At first, Johnson only slightly expanded the U.S. presence in South Vietnam, sending in 5,000 military advisers. Gulf of Tonkin Resolution: In Aug. 1964, LBJ announced that two U.S. destroyers on patrol in international waters in the Gulf of Tonkin had been attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. While later information raised doubts about this incident, Congress passed the “Gulf of Tonkin Resolution” that stated that the president could “take all necessary measures” to protect U.S. forces in the region. LBJ saw this as a mandate to escalate the U.S. presence. Escalation: After communist forces attacked a U.S. air base at Pleiku in Feb. 1965, Johnson ordered the bombing of the North to destroy supply lines to the South; these bombings continued intermittently until 1972. In March 1965, more Marines landed at Danang, bringing the total U.S. presence to 100,000. By end of 1967, the number reached 500,000. 38 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Agony of Vietnam – The Quagmire “Attrition” Strategy: This strategy was based on the belief that the U.S. could inflict more damage on its enemies than they could absorb, but the communists saw the war as a fight for independence and were willing to commit a lot more troops and resources than the U.S. military predicted. Ineffectiveness of Bombing: Bombing the North did not help much because North Vietnam was not a developed and industrialized country with targets that would make bombing effective. They also responded to the bombing by building vast underground complexes and moving the supply lines from the North around constantly. “Pacification”: The American military thought it could route the NLF from certain areas and the win the “hearts and minds” of the locals to keep the NLF out. But when this failed, the generals relied on relocating villagers and burning down their villages, which created considerable animosity and about three million internal refugees. 39 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The War in Vietnam and Indochina, 1964-1975 40 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Agony of Vietnam – The War at Home Protesters face off against soldiers in the 1967 D.C. peace march. Growing Antiwar Movement: In 1965, only a small number of Americans were protesting the war. In 1966, the boxer Muhammad Ali refused to register for the draft. But by the end of 1967, students protesting the war had become a significant political force. That year, peace marches in New York, Washington D.C., and San Francisco crowds of 100,000 or more. Senator J. William Fulbright of Arkansas, chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, turned against it in 1966, while Robert F. Kennedy, senator from New York, did so in 1967. War-Induced Inflation: With war spending and Great Society programs pouring money into the economy, inflation began to get out of control. Rising from the 2 percent of the early 1960s to 6 percent by 1969. Conservatives demanded $6 billion cuts from Great Society programs in exchange for the tax increase needed to slow inflation. 41 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Traumas of 1968 – The Tet Offensive The Shock of Tet: On Jan. 31, 1968—the beginning of the Vietnamese New Year celebration—communist forces launched a massive coordinated attack on American strongholds throughout Vietnam, and several cities fell temporarily to the communists. The NLF penetrated deep into the capital of Saigon, setting off bombs, shooting South Vietnamese soldiers, and even attacking the U.S. embassy, all in front of TV cameras. Political Defeat: U.S. forces soon dislodged the NLF from most of the positions it gained during the Tet attack and resulted in enormous loss of soldiers for the NLF. But it was a political loss for LBJ’s administration, which had been telling the public for years that war effort was going well. Tet undermined public confidence, and public opposition to the war doubled in the following weeks. The president’s popularity rating sank to 35 percent, which had not happened since the Truman administration. 42 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Widely disseminated image of the summary execution of NLF soldier by a South Vietnamese army office South Vietnamese Police Chief General Nguyen Ngoc Loan in Saigon during the Tet Offensive, which alerted the Americans to the level of brutality of the fighting in Vietnam. Photo by Eddie Adams. 43 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism Map indicating all of the major coordinated attacks during the Tet Offensive 44 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Traumas of 1968 – The Political Challenge 45 Eugene McCarthy RFK Eugene McCarthy (1916-2005): When Robert Kennedy turned down the offer to run for president by anti-war Democrats in the summer of 1967, they turned to McCarthy, a senator from Minnesota, who nearly defeated the president in the New Hampshire primary in March 1968. McCarthy ran because he saw the Vietnam conflict as “an immoral war.” Robert F. Kennedy (1925-1968): A few days later, RFK changed his mind and decided to run, angering McCarthy supporters. Polls showed LBJ trailing in the next primary in Wisconsin. LBJ Drops Out: On March 31, 1968, LBJ went on TV to announce that he would halt bombing of North Vietnam, but also, rather shockingly, that he had decided not to seek reelection. Hubert Humphrey (1911-1978): Johnson’s vice president and former senator from Minnesota, also entered the race, and garnered favor with party leaders. He soon became the front runner in the race. Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Traumas of 1968 – The King Assassination Memphis Sanitation workers on strike King in Memphis: King had come to Memphis in March 1968 to support a strike of black sanitation workers, who were protesting brutal working conditions. On April 4, he was shot and killed on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, where he had been staying. James Earl Ray (1928-1998): While a George Wallace supporter and a racist, Ray did not have a clear motive for the assassination. Some evidence suggest that Ray was hired for the killing, but he never divulged who might have employed him. Riots: The news of King’s death triggered major riots in sixty American cities, which killed forty-three people. 46 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Traumas of 1968 – The Kennedy Assassination and Chicago Robert Kennedy Assassinated: After an appearance at the ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, Kennedy was shot in the head while passing through the hotel’s kitchen by Sirhan Sirhan (1946-), a Christian Palestinian who had been angered by some earlier proIsraeli remarks that Kennedy had made. Kennedy died a few hours later, causing shock across the nation still on edge from King’s death. Democratic National Convention: When the Democrats met for their Convention in Chicago in August, the nomination of Humphrey appeared inevitable. But as Humphrey received his nomination on the third night, thousands of anti-war protesters in a park a few miles were attacked by police with tear gas and billy clubs, stealing television coverage from Humphrey. The protestors chanted, “The whole world is watching!” as police beat them. 47 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Traumas of 1968 – The Kennedy Assassination and Chicago 48 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Traumas of 1968 – The Conservative Response Revolutionary Change? Many Americans thought the U.S. was on the verge of revolutionary change, but many voters turned toward conservatives. George C. Wallace (1919-1998): The surprising success of this Alabama governor’s presidential run on the third-party ticket of the American Independent Party, winning over 9.9 million votes in the popular vote (12.9 percent) and 46 Electoral College votes. He ran on a segregationist and law-and-order line that appealed even to some alienated working-class whites in the North. Nixon Elected: Nixon had lost both the presidential campaign in 1960 and the California governor’s race in 1962, but reemerged in 1968 as a spokesman of what he called the “silent majority.” His policy of law-and-order, stability, and “peace with honor” in Vietnam won him a narrow victory over Humphrey. 49 Chapter Twenty-Nine: Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the Ordeal of Liberalism The Election of 1968 50