Development Economics: Models of Underdevelopment

advertisement

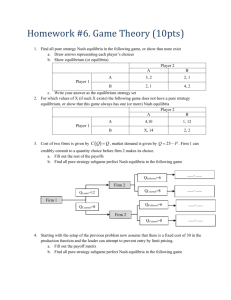

Chapter 4A Contemporary Models of Development and Underdevelopment 4.1 Underdevelopment as a Coordination Failure 0 A newer school of thought on problems of economic development 0 Coordination failures occur when agents’ inability to coordinate their actions leads to an outcome that makes all agents worse off. 0 This can occur when actions are complementary, i.e., 0 Actions taken by one agent reinforces incentives for others to take similar actions 1 4.2 Multiple Equilibria: A Diagrammatic Approach 0 Often, these models can be diagrammed by graphing an S-shaped function and the 45º line 0 Equilibria are 0 Stable: function crosses the 45º line from above 0 Unstable: function crosses the 45º line from below Figure 4.1 Multiple Equilibria 2 4.3 Starting Economic Development: The Big Push 0 Sometimes market failures lead to a need for public policy intervention 0 The Big Push: A Graphical Model, 6 assumptions 0 0 0 0 0 0 One factor of production Two sectors Same production function for each sector Consumers spend an equal amount on each good Closed economy Perfect competition with traditional firms operating, limit pricing monopolist with a modern firm operating 0 Conditions for Multiple Equilibria 0 A big push may also be necessary when there are: 0 0 0 0 Intertemporal effects Urbanization effects Infrastructure effects Training effects 3 Figure 4.2 The Big Push Why the Problem Cannot be Solved by a Super-Entrepreneur Super Entrepreneur? Capital market failures Cost of monitoring managersAsymmetric Information Communication failures Limits to knowledge Lack of any empirical evidence that would suggest this is possible 4 In a Nutshell: Big Push Mechanisms 0 Raising total demand 0 Reducing fixed costs of later entrants 0 Redistributing demand to later periods when other industrializing firms sell 0 Shifting demand toward manufacturing goods (usually produced in urban areas) 0 Help defray costs of essential infrastructure (a similar mechanism can hold when there are costs of training, and other shared intermediate inputs) 5 4.4 Further Problems of Multiple Equilibria 0 Inefficient Advantages of Incumbency 0 Behavior and Norms 0 Linkages 0 Inequality, Multiple Equilibria, and Growth 4.5 Michael Kremer’s O-Ring Theory of Economic Development 0 The O-Ring Model 0 Production is modeled with strong complementarities among inputs 0 Positive assortative matching in production 0 Implications of strong complementarities for economic development and the distribution of income across countries 6 4.6 Economic Development as Self-Discovery 0 Hausmann and Rodrik: A Problem of Information 0 Not enough to say developing countries should produce “labor intensive products,” because there are thousands of them 0 Industrial policy may help to identify true direct and indirect domestic costs of potential products to specialize in, by: 0 Encouraging exploration in first stage 0 Encouraging movement out of inefficient sectors and into more efficient sectors in the second stage 7 4.6 Economic Development as Self-Discovery 0 Three building blocks of the theory; and case examples of their reasonableness in practice: 0 Uncertainty about products can produce efficiently (evidence: India’s success in information technology was unexpected; reasons for Bangladesh’s efficiency in hats vs Pakistan’s in bedsheets is not clear) 0 Need for local adaptation (evidence: seen in cases such as shipbuilding in South Korea) 0 Imitation can be rapid (e.g. the spread of cut flower exporting in Colombia) 8 4.7 The Hausmann-Rodrik-Velasco Growth Diagnostics Framework 0 Focus on a country’s most binding constraints on economic growth 0 No “one size fits all” in development policy 0 Requires careful research to determine the most likely binding constraint 9 The Hausmann-Rodrik-Velasco Growth Diagnostics Framework;1 1. Specialization – specifics beyond comparative advantage, i.e. labor- intensive activities is hardly enough. The idea behind “self-discovery” --figuring out what the impediments to growth are. 2. The building towards self-discovery recognizes 3 building blocks: a. Uncertainty about what a developing country can produce costeffectively and also profitably. b. Need for the local adaption of imported technology to prevent easy entry – might require local reverse engineering. c. With (a) and (b) in place, “imitation” is very rapid. It shows as many countries who are labor-intensive will produce different labor intensive products. 3. Growth Diagnostics (GD)– once efficient investment & entrepreneurship are accepted for economic growth & development, there is need for country-specific binding constraints. GD is a decision tree for identifying the most binding constraints for each country currently and in future. 10 The Hausmann-Rodrik-Velasco Growth Diagnostics Framework;2 1. Focus on a country’s most binding constraints on economic growth & alleviating pressing constraints. 2. Suppose a country is constrained by low level of private investment & entrepreneurship. The decision tree identifies the-how-to-solve the problem. The initial causes could be (a) low return to economic activity and (b) high cost of finance. 3. Not that the solution to these binding constraints are so many and multi-dimensional. This shows that No “one size fits all” in development policy, i.e. GD is a much more broader approach to development policy that complements econometric modelling. 0 Not simple to find the binding constraint. Uncertainty leads to probabilistic assessments 11 Figure :Hausmann-Rodrik-Velasco Growth Diagnostics Decision Tree 12 The Hausmann-Rodrik-Velasco Growth Diagnostics Framework;3 Growth diagnostics 1. Key constraint is inadequacy of public goods especially on 2 emerging sectors (tourism & light manufacturing). 2. Financial sector constraints –credit and loans Signals Problem of “arriving late” for public events Illustrates the idea of multiple equilibria --- moving from one inferior equilibrium to a superior one 4-13