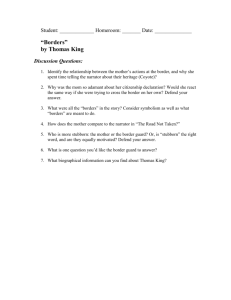

File - English 1120

advertisement

Friday, February 17 Thomas King’s “Borders” Thomas King’s “Borders” “I’d be proud of being Blackfoot if I were Blackfoot. But you have to be American or Canadian.” “They mostly talked to my mother. Every so often one of the reporters would come over and ask me questions about how it felt to be an Indian without a country. I told them we had a nice house and that my cousins had a couple of horses we rode when we went fishing. Some of the television people went over to the American border, and then they went to the Canadian border.” “She was serious about it, too. She’d tell them slow, repeating parts as she went, as if she expected me to remember each one.” “As King contrasts the blinding glare of TV lights with the muted glow of the stars, he also contrasts the careful pedagogy underlying the mother's repetition of Creation stories with the synchronous repetition of the quickly forgotten news story on TV sets across North America, and with the hollowness of the guards’ repeated demands that she comply with the narrative of federal citizenship.” — Carrie Dawson (“An Indian Without a Country” 26) “With the phrase ‘rolled over a hill and disappeared’ King reverses the formulation familiar from so many Westerns - wherein the calamitous appearance of Indians from over a hill (as though from nowhere) and their certain disappearance back over a hill (to nowhere) suggests that they have no place in that landscape. In King's formulation, the victorious Indians are going home and the flagpoles roll over the hill and disappear.” — Carrie Dawson (“An Indian Without a Country” 26) “and the border’s not going anywhere and we keep constructing new borders. As soon as we get rid of the old ones we construct new ones. The big joke for me always was — and this is pretty well documented — that rich black women get along with rich white women better than they get along with poor black women. So you have ail these borders that cut right through race too. Race is not a common denominator particularly. In some ways it is and in some ways it is not. You've got race, economies, social standing. All these things just sort of mix and match around.” — Thomas King in “Border Trickery and Dog Bones: A Conversation with T.K.”164) “As King’s texts demonstrate, dispersed across the traditional borders of the nation-state are other nations, races, ethnicities, and cultures—such as those of First Nations peoples—divided by the traditional imperialist demarcations. Native lands, in a sense, lie “inbetween” the borders of the nation-state because they are affected by them, but they are also conceived of as independent places by the tribes who reside on them. For aboriginals, the space between the borders of the nation-state and the lands that were historically occupied by Native North American tribes generates gaps in conventional notions of nationhood that allow King and other writers responsive to a tribal vision to explore alternative definitions of identity and community.” — Jennifer Andrews and Priscilla L. Walton (“Rethinking Canadian and American Nationality: Indigeneity and the 29th Parallel in Thomas King” 601). “King depicts the Canadian–US border as a place of multiple, shifting contact zones, national and tribal, constantly subject to change. His critical focus on the 49th parallel shifts the terms of debates over border studies northward, across the hemisphere, to a border that marks (an)Other legacy of differences. — Jennifer Andrews and Priscilla L. Walton (“Rethinking Canadian and American Nationality: Indigeneity and the 29th Parallel in Thomas King” 601). “Being inside and outside the borders does not mean that one is immune to or from them; rather, it suggests that from in-between, one can view either side, perhaps rejecting both, but also acknowledging how those ‘sides’ influence one’s own spatial position.” — Jennifer Andrews and Priscilla L. Walton (“Rethinking Canadian and American Nationality: Indigeneity and the 29th Parallel in Thomas King” 605). “As King’s 1993 short story “Borders” demonstrates, the 49th parallel can be used as a site of resistance to imperialist definitions that preclude Native self-definition, although, again, such challenges seem to bring about only temporary, not fundamental, changes. In this story, King pointedly subverts the concept of border “in-between-ness” by reminding readers that such utopian ideals and spaces ignore the daily realities of Native peoples, whose identities have been fractured by the lasting effects of colonialism on the local populations.” — Jennifer Andrews and Priscilla L. Walton (“Rethinking Canadian and American Nationality: Indigeneity and the 29th Parallel in Thomas King” 606-607). “The counter-narratives or alternative visions within King’s texts also perform a political purpose, for they create a gap that induces cultural resistance to the dominance of nation. King’s texts, as they critique the nation-state in which they are situated, problematize the object of colonization and thus emerge as cross-cultural texts that demand cross-cultural readings. They encourage a resistance to political amnesia and insist on the importance of acknowledging and exploring the contradictions of colonizing histories, especially when relayed by those under colonial rule.” — Jennifer Andrews and Priscilla L. Walton (“Rethinking Canadian and American Nationality: Indigeneity and the 29th Parallel in Thomas King” 609). Sample Exam Questions Section I: Definitions of Literary Terms (value = 10%; 2 marks per definition; must define 5 of 10 terms) Provide a clear and thorough definition of the following terms: Setting Postcolonial Criticism Agency Section II: Close-reading and Analysis (30%; 10 marks per question) In a substantial paragraph, provide a close-reading of 3 of the following 5 passages. Before you begin writing your paragraph, scan and annotate the passage. Then, dissect the language and word choice of the passage, interpret your findings/annotations/connections, and comment upon the significance/meaning of the passage to the story and its theme(s). Note: You are not expected to formulate a thesis statement for your responses in this section (the emphasis here is on analysis, not argumentation). “My father did not tan—he never tanned—because of his reddish complexion, and the salt water irritated his skin as it had for sixty years. He burned and reburned over and over again and his lips still cracked so that they bled when he smiled, and his arms, especially the left, still broke out into the oozing saltwater boils as they had ever since as a child I had first watched him soaking and bathing them in a variety of ineffectual solutions. The chafe-preventing bracelets of brass linked chain that all the men wore about their wrists in early spring were his the full season and he shaved but painfully and only once a week” — from Alistair MacLeod’s “The Boat” Section III: Essay Response (60%)—choice of 3 essay questions Write a well-organized essay (miminum 5 paragraphs) response to the following question: In “Bartleby, the Scrivener” and “The Boat,” the geographical locations of the stories serve as both setting and symbol. Write a well-organized, analytical essay examining the relationship between setting and symbol in the aforementioned texts. Notes: You must include an introduction (with thesis!), body paragraphs, and a conclusion. You will be marked on formatting and structure. You may work on texts you have identified in the previous section, but you must not discuss the same aspects of the stories (tip: it might be a good idea to avoid discussing the same stories twice; part of the purpose of this exam is to show breadth of knowledge).