MN50324-2012

advertisement

MN50324: Corporate Finance 2011/12:

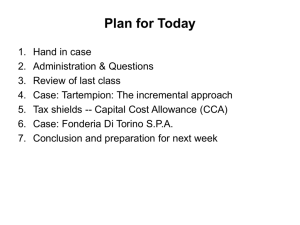

1. Investment flexibility, Decision trees, Real Options

2. Asymmetric Information and Agency Theory

3. Capital Structure and Value of the Firm.

4. Optimal Capital Structure - Agency Costs, Signalling

5. Dividend policy/repurchases

6. Mergers and Acquisitions/corporate control

7. Venture Capital/Private Equity/hedge funds

8. Behavioural Corporate Finance.

9. Emotional Corporate Finance

10. Revision.

1

1: Investment Flexibility/ Real

options.

• Reminder of Corporation’s Objective :

Take projects that increase shareholder

wealth (Value-adding projects).

• Investment Appraisal Techniques: NPV,

IRR, Payback, ARR

• Decision trees

• Real Options

• Game-theory approach!

2

Investment Flexibility, Decision Trees, and Real

Options

Decision Trees and Sensitivity Analysis.

•Example: From Ross, Westerfield and Jaffe: “Corporate Finance”.

•New Project: Test and Development Phase: Investment

$100m.

•0.75 chance of success.

•If successful, Company can invest in full scale

production, Investment $1500m.

•Production will occur over next 5 years with the

following cashflows.

3

Production Stage: Base Case

$000

Year 1

Year 2 - 6

Revenues

Variable Costs

Fixed Costs

Depreciation

6000

-3000

-1791

-300

Pretax Profit

Tax (34%)

909

-309

Net Profit

Cashflow

600

900

Initial Investment

-1500

6

900

Date 1 NPV = -1500 +

t

(

1

.

15

)

t 2

= 1517

4

Decision Tree.

Date 1: -1500

Date 0: -$100

P=0.75

Success

Test

Invest

NPV = 1517

Do not Invest

NPV = 0

Do not Invest

Failure

P=0.25

Do Not Test

Invest

NPV = -3611

Solve backwards: If the tests are successful, SEC should invest,

since 1517 > 0.

If tests are unsuccessful, SEC should not invest, since 0 > -3611.

5

Now move back to Stage 1.

Invest $100m now to get 75% chance of $1517m one year later?

Expected Payoff = 0.75 *1517 +0.25 *0 = 1138.

NPV of testing at date 0 = -100 + 1138 = $890

1.15

Therefore, the firm should test the project.

Sensitivity Analysis (What-if analysis or Bop analysis)

Examines sensitivity of NPV to changes in underlying

assumptions (on revenue, costs and cashflows).

6

Sensitivity Analysis.

- NPV Calculation for all 3 possibilities of a single variable +

expected forecast for all other variables.

NPV

Market Size

Market Share

Price

Variable Cost

Fixed Cost

Investment

Pessimistic

-1802

-696

853

189

1295

1208

Expected

or Best

1517

1517

1517

1517

1517

1517

Optimistic

8154

5942

2844

2844

1628

1903

Limitation in just changing one variable at a time.

Scenario Analysis- Change several variables together.

Break - even analysis examines variability in forecasts.

It determines the number of sales required to break even.

7

Real Options.

A digression: Financial Options (revision)

A call option gives the holder the right (but not the obligation) to

buy shares at some time in the future at an exercise price agreed

now.

A put option gives the holder the right (but not the obligation) to

sell shares at some time in the future at an exercise price agreed

now.

European Option – Exercised only at maturity date.

American Option – Can be exercised at any time up to maturity.

For simplicity, we focus on European Options.

8

Example:

• Today, you buy a call option on Marks and

Spencer’s shares. The call option gives you the

right (but not the obligation) to buy MS shares at

exercise date (say 31/12/10) at an exercise price

given now (say £10).

• At 31/12/10: MS share price becomes £12. Buy at

£10: immediately sell at £12: profit £2.

• Or: MS shares become £8 at 31/12/10: rip option

up!

9

Factors Affecting Price of European Option (=c).

-Underlying Stock Price S.

-Exercise Price X.

-Variance of of the returns of the underlying asset ,

2

-Time to maturity, T.

c

c

c

c

0,

0, 2 0,

0.

S

X

T

The riskier the underlying returns, the greater the probability that

the stock price will exceed the exercise price.

The longer to maturity, the greater the probability that the stock

price will exceed the exercise price.

10

Options: Payoff Profiles.

Selling a put option.

Buying a Call Option.

W

S

Selling a Call Option.

Buying a Put Option.

11

Pricing Call Options – Binomial Approach.

Cu = 3

uS=24.00

q

q

c

S=20

1- q

dS=13.40

1- q

Cd=0

S = £20. q=0.5. u=1.2. d=.67. X = £21.

1 + rf = 1.1.

Risk free hedge Portfolio: Buy One Share of Stock and write m

call options.

uS - mCu = dS – mCd => 24 – 3m = 13.40.

M = 3.53.

By holding one share of stock, and selling 3.53 call options, your

12

payoffs are the same in both states of nature (13.40): Risk free.

Since hedge portfolio is riskless:

(1 rf )( S mc) uS mcu .

1.1 ( 20 – 3.53C) = 13.40.

Therefore, C = 2.21.

This is the current price per call option. The total present value of

investment = £12 .19, and the rate of return on investment is

13.40 / 12.19 = 1.1.

13

Alternative option-pricing method

• Black-Scholes

• Continuous Distribution of share returns

(not binomial)

• Continuous time (rather than discrete time).

14

Real Options

• Just as financial options give the investor the right

(but not obligation) to future share investment

(flexibility)

• Researchers recognised that investing in projects

can be considered as ‘options’ (flexibility).

• “Real Options”: Option to delay, option to

expand, option to abandon.

• Real options: dynamic approach (in contrast to

static NPV).

15

Real Options

• Based on the insights, methods and

valuation of financial options which give

you the right to invest in shares at a later

date

• RO: development of NPV to recognise

corporation’s flexibility in investing in

PROJECTS.

16

Real Options.

• Real Options recognise flexibility in

investment appraisal decision.

• Standard NPV: static; “now or never”.

• Real Option Approach: “Now or Later”.

• -Option to delay, option to expand, option

to abandon.

• Analogy with financial options.

17

Types of Real Option

• Option to Delay (Timing Option).

• Option to Expand (eg R and D).

• Option to Abandon.

18

Option to Delay (= call option)

•

Investment in

waiting:

Valuecreation

Project

value

(sunk)

19

Option to expand (= call option)

Value creation

•

Investment in

initial project:

eg R and D

(sunk)

Project

value

20

Option to Abandon ( = put option)

•

Project goes

badly: abandon

for liquidation

value.

Project

value

21

Valuation of Real Options

• Binomial Pricing Model

• Black-Scholes formula

22

Value of a Real Option

• A Project’s Value-added = Standard NPV

plus the Real Option Value.

• For given cashflows, standard NPV

decreases with risk (why?).

• But Real Option Value increases with risk.

• R and D very risky: => Real Option element

may be high.

23

Comparing NPV with Decision

Trees and Real Options (revision)

E ( FCF1 )

NPV I t 1

0

t

(1 WACC )

N

•Dixit and Pyndyck (1994): Simple Example: Decide

today to:

•Invest in a machine at end of year: I = £1,600.

•End of year: project will be worth 300 (good state

forever) or 100 (bad state forever) with equal probability.

•WACC = 10%.

•Should we invest?

24

Dixit and Pyndyck example

• Either pre-commit today to invest in a

machine that will cost £1,600 at year end.

• Or defer investment to wait and see.

• Good state of nature (P = 0.5): product will

be worth £300.

• Bad state of nature (P = 0.5): product will

be worth £100.

25

NPV of project under precommitment

•

NPV1 1,600 0.5(300 100) t 1

1,600 200

0.5(300 100)

(1.1) t

200

600

0.1

=>

600

NPV0

545.5

1.1

26

Value with the option to defer

• Suppose cost of investment goes up to £1,800 if

we decide to wait (so, cost of waiting).

• Year end good state:

•

300

NPV 1800 300

1500

0.1

• Year-end bad state:

100

NPV 1800 100

700

0.1

27

Value with option to defer

(continued)

•

0.5(1500)

NPV0

681.80

1.1

Therefore, deferring adds value of £136.30.

Increasing uncertainty; eg price in good or bad state =

400 or zero (rather than 300 or 100)

=> Right to defer becomes more valuable.

28

Comparing NPV, decision trees and

Real Options (continued)

•

0.5

300

300

1,600

0.1

545.5

Invest 0.5

300

100

1,600

0 .1

Pre-commitment to invest

29

Comparing NPV, decision trees and

Real Options (continued)

•

0.5

Invest

V= 681.8

Defer

Max{1500,0}

0.5

Max {-700,0}

Don’t Invest

Value with the option to defer

30

Simplified Examples

• Option to Expand (page 241 of RWJ)

If Successful

Expand

Build First Ice

Hotel

Do not Expand

If unsuccessful

31

Option to Expand (Continued)

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

NPV of single ice hotel

NPV = - 12,000,000 + 2,000,000/0.20 =-2m

Reject?

Optimistic forecast: NPV = - 12M + 3M/0.2

= 3M.

Pessimistic: NPV = -12M + 1M/0.2 = - 7m

Still reject?

32

Option to expand (continued)

• Given success, the E will expand to 10

hotels

• =>

• NPV = 50% x 10 x 3m + 50% x (-7m) =

11.5 m.

• Therefore, invest.

33

Option to abandon.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

NPV(opt) = - 12m + 6m/0.2 = 18m.

NPV (pess) = -12m – 2m/0.2 = -22m.

=> NPV = - 2m. Reject?

But abandon if failure =>

NPV = 50% x 18m + 50% x -12m/1.20

= 2.17m

Accept.

34

Real Option analysis and Game

theory

• So far, analysis has assumed that firm

operates in isolation.

• No product market competition

• Safe to delay investment to see what

happens to economy.

• In real-world, competitors (vultures)

• Delay can be costly!

35

Option to delay and Competition

• Smit and Ankum model (1993)

• Option to defer an investment in face of

competition

• Combines real options and Game-theory.

• Binomial real options model: lends itself

naturally to sequential game approach (see

exercise 1).

36

Option to delay and competition

(continued)

• Smit and Ankum incorporate game theory

(strategic behaviour) into the binomial pricing

model of Cox, Ross and Rubinstein (1979).

• Option to delay increases value (wait to observe

market demand)

• But delay invites product market competition:

reduces value (lost monopoly advantage).

• cost: Lost cash flows

• Trade-off: when to exercise real option (ie when to

delay and when to invest in project).

37

Policy implications of Smit and

Ankum analysis.

• How can firm gain value by delaying

(option to delay) in face of competition?

• Protecting Economic Rent: Innovation,

barriers to entry, product differentiation,

patents.

• Firm needs too identify extent of

competitive advantage.

38

Real Options and Games (Smit and

Trigeorgis 2006)

• Game theory applied to real R and

D/innovation cases:

• Expanded (strategic) NPV = direct (passive)

NPV + Strategic (commitment) value +

flexibility Value.

• Innovation race between Philips and Sony

=> Developing CD technology.

39

P\S

Wait

Invest

Wait

300, 300

0, 400

Invest

400, 0

200, 200

Each firm’s dominant strategy: invest early: =>

Prisoner’s dilemma.

How to collaborate/coordinate on wait, wait?

40

Asymmetric Innovation Race/

Pre-emption

• Asymmetry: P has edge in developing technology,

but limited resources.

• S tries to take advantage of this resource weakness

• Each firm chooses effort intensity in innovation

• Low effort: technology follower, but more

flexibility in bad states

• High effort: technology leader, higher

development costs, more risk in bad state.

41

•

P\S

Low effort

High

Low

200, 100

10, 200

High

100, 10

-100, -100

“Grab the dollar” game

42

Sequential Investment Game

•

High effort

-100m,-100m

S

High effort

Low effort

100m, 10m

P

High effort

10m, 200m

Low effort

S

Low effort

200m, 100m

43

European Airport Expansion Case:

Real Options Game (Smit 2003)

•

44

Two-stage Investment Game (Imai

and Watanabe 2004)

•

45

Option to delay versus competition:

Incorporating contracts/ Legal system (RF)

Firm 1\Firm 2

Invest early

Delay

Invest early

NPV = 500,NPV = 500

NPV = 700, NPV = 300

Delay

NPV = 300, NPV = 700

NPV = 600,NPV = 600

46

Option to delay versus competition:

Incorporating contracts/ Legal system

(continued)

Firm 1\ Firm 2

Invest early

Delay

Invest early

NPV = 500,NPV = 500

NPV = 700- 300, NPV =

300+300

Delay

NPV = 300+300, NPV =

700-300

NPV = 600,NPV = 600

47

Use of Real Options in Practice

48

• In practice, NPV not always used:Why Not?.

• -Agency (incentive) problems: eg Short-term

compensation schemes => Payback.

• Behavioural:• Managers prefer % figures => IRR, ARR

• Managers don’t understand NPV/ Complicated

Calculations.

• Payback simple to calculate.

• Other Behavioural Factors (see later section on

Behavioural Finance!!)

• Increase in Usage of correct DCF techniques

(Pike):

• Computers.

• Management Education.

49

Game-theoretic model of NPV.

• Israel and Berkovitch RFS 2004.

• NPV is seen as standard value-maximising

technique.

• But IB’s game-theoretic approach considers

the impact of agency and assymetric

information problems

50

Israel and Berkovitch (continued)

•

•

•

•

A firm consisting of two components:

1: Top management (Headquarters)

2. divisional managers (“the manager”).

Objective of headquarters: Maximisation of

shareholder value.

• Objective of manager: maximise her own

utility.

51

Israel and Berkovitch (continued)

• HQ needs to design a monitoring and

incentive mechanism to deal with these

conflicting objectives.

• => capital allocation system specifying:

• A capital budgeting rule (eg NPV/IRR) and

a wage compensation for divisional

managers.

52

Israel and Berkovitch

• Paper demonstrates the ingredients of a

game-theoretic approach.

• Players.

• Objectives (utility functions to maximise)

• Strategies.

• Payoffs.

53

2. Information Asymmetry/Agency

Theory

• Chapter 12 CWS.

• We will see that info assymetry and agency

theory play a large role in CF analysis.

• Investment appraisal, capital structure,

dividend policy

• => Game theory

54

Game theory

• Players (eg managers/investors: or competing

companies)

• Actions (eg invest in a project, issue debt, pay

dividends etc)

• Strategies

• Payoffs/ optimisation.

• Equilibrium: eg good firm issues high debt, bad

firm issues low debt.

• Or Good firm pays high dividends, bad firm pays

low dividends.

55

Information Asymmetry

• Insiders/managers better informed than

investors about projects, prospects etc.

• Managerial actions (eg capital structure

choices: debt/equity issues, dividends,

repurchases) may reveal information to the

market

• Signalling models of debt, dividends,

repurchases

56

Asymmetric info/signalling models

• Typically, two types of firm: High quality/low

quality.

• Type unobservable to outside investors

• Manager of High quality firm would like to signal

his type to market.

• Costly signals

• Cheap-talk signals.

• Eg level of investment, amount of debt, size of

dividend.

57

Pooling versus separating equilibria

• Separating equilibrium: good firm can separate for

bad firm eg by higher debt

• Cost of signal: eg expected financial distress

• Separation requires cost of signal => bad firm

cannot (or is unwilling) to mimic good firm’s debt

level.

• Separation: outsiders can determine firm types

• Pooling: outsiders cannot differentiate between the

two types

58

Corporate Finance: Signalling

Models

• Based on models from Informational

Economics.

• Eg Akerlof (1970): price signals of quality

in used car market (mkt for Lemons!)

• Spence (1973): education as signals of skill

in job market.

• Myers-Majluf (1984): equity-signalling

model based on Akerlof’s Lemons market!

59

Major CF signalling models

• Signalling project quality with investment

(Leland and Pyle 1977)

• Signalling firm quality with debt (Ross

1977)

• Signalling expected cashflows with

dividends (Bhattacharya 1979)

• Signalling and the equity issue-invest

decision (Myers-Majluf 1984)

60

Stock Split signalling

• Copeland and Brennan 1988

• Brennan and Hughes 1991.

• Debt/equity Heinkel 1982

61

CF and Agency Theory

• Standard CF statement: the firm aims to

maximise shareholder wealth => NPV rule.

• But agency theory =>

• Separation of Ownership and control

• Principal/agent relationship

• Outside investors = Principal

• Manager = agent

62

Agency theory (contiuned)

• Manager self-interested.

• he may takes private benefits (perks) out of the

firm

• Invest in favourite (pet) projects: empire-builder

(eg rapid value-destroying growth => mergers?)

• Effort-shirking

• Capital structure/dividends may serve to align

managers’ and investors’ interests.

63

2. Cost of Capital/discount

rate/investors’ required return.

• What discount rate to use in NPV/

valuation?

• Portfolio analysis => Investors’ required

return as a compensation for risk

• => CAPM (capital asset pricing model) =>

cost of equity (risk-averse equity-holders’

required return): increases with risk.

64

Cost of Capital/discount rate/investors’

required return (continued).

• Cost of debt (debt-holders’ required return).

• Capital structure (mix of debt and equity).

• => discount rate/cost of capital/investors’

required return=>

WACC %debt * K d %equity * Ke .

65

Example

• New project: initial investment I £1000

• Project expected to generate £150 per year forever

(perpetuity)

• Kd=5%, Ke = 15% (Capital structure =50%

debt/50% equity)

• Consider Market Value of firm’s debt = market value

of firms equity=> WACC = 10%.

NPV 1000

150

500

0.10

66

Firm Valuation (CWS Chapter 14)

• Formula Approach for Valuing Companies

t0

V0

t1

t2

EBIT1 (1 T ) I1

tN

EBIT1 (1 T ) t 1 rt I t I N

N 1

EBIT2 (1 T ) I 2

EBIT1 (1 T ) r1 I1 I 2

67

Valuation of all-equity firm with

growth

EBIT1 (1 T ) I1

V1

V0

1 KU

1 KU

=>

EBIT N (1 TC ) I N

EBIT1 (1 T ) I1 EBIT2 (1 T ) I 2

V0

...

2

1 KU

(1 KU )

(1 KU ) N

68

Valuation of all-equity firm with

growth (continued)

EBITt (1 T ) I t

V0 t 1

(1 kU )t

N

•Present value of the firm is the sum of discounted

cashflows from operations less new investments

required for growth

•Fundamental Value (= market value? Efficient mkts/

BCF)

•Dividend policy (dividends versus investment for

growth)

69

Valuation of all-equity firm with

growth (continued)

I t (rt KU )

EBIT1 (1 T )

V0

t 1

t

KU

KU (1 KU )

V0 = value of assets in place + value of future

growth

70

Infinite constant growth model

I t K ( EBITt (1 T ))

EBITt (1 T ) EBITt 1 (1 T ) rI t 1

EBIT (1 T ) rK ( EBITt 1 (1 T ))

EBITt 1 (1 T )(1 rK )

=>

EBITt (1 T ) EBIT1 (1 T )(1 rK )t 1

=>

EBITt (1 T ) EBIT1 (1 T )(1 g )t 1

71

By substitution:

K (r kU ) 1 rK t

EBIT1 (1 T )

V0

[1

(

)]

t 1

KU

1 rK

1 kU

But:

1 rK t

1 rK

t 1 ( 1 k ) ] k rK

U

U

=>

V0

EBIT1 (1 T )(1 K )

Div1

kU Kr

kU g

Gordon Growth

Model:

Consider later in

div policy lecture

72

3. Capital Structure.

Positive NPV project immediately increases current equity

value (share price immediately goes up!)

Pre-project announcement

V Bo Eo

I

New capital (all equity)

New project:

Value of Debt

Original equity holders

New equity

New Firm Value

NPV Vn I .

Bo

E0 Vn I

I

V Vn

73

Example:

V Bo Eo

I

=500+500=1000.

20

NPV Vn I

60 -20 = 40.

Bo

Value of Debt

Original Equity

E0 Vn I

New Equity

I

= 20

V Vn

=1000+60=1060.

Total Firm Value

= 500.

= 500+40 = 540

74

Positive NPV: Effect on share price.

Assume all equity.

£K

Current

Market

Value

No of

Shares

1000

New Project

Project Income

60

Required Investment

20

NPV

40

1000

Price per

Share

1

Market

Value

No of

Shares

Price per

Share

1040

1000

1.04

20

19

1.04

1060

1019

1.04

75

Value of the Firm and Capital Structure

Value of the Firm = Value of Debt + Value of Equity = discounted

value of future cashflows available to the providers of capital.

(where values refer to market values).

Capital Structure is the amount of debt and equity: It is the way a firm

finances its investments.

Unlevered firm = all-equity.

Levered firm = Debt plus equity.

Miller-Modigliani said that it does not matter how you split the cake

between debt and equity, the value of the firm is unchanged (Irrelevance

Theorem).

76

Value of the Firm = discounted value of future cashflows available to

the providers of capital.

-Assume Incomes are perpetuities.

Miller- Modigliani Theorem:

VU

NCF (1 T )

VE

NCF (1 T )

VL VU T .B

VE VD

WACC

NI kd .B

.

K

Kd

e

Irrelevance Theorem: Without Tax, Firm Value is

independent of the Capital Structure.

Note that

WACC %debt * K d (1 t ) %equity * K e

77

K

K

Without Taxes

D/E

With Taxes

D/E

V

V

D/E

78

D/E

Examples

• Firm X

• Henderson Case study

79

MM main assumptions:

- Symmetric information.

-Managers unselfish- maximise shareholders wealth.

-Risk Free Debt.

MM assumed that investment and financing decisions

were separate. Firm first chooses its investment projects

(NPV rule), then decides on its capital structure.

Pie Model of the Firm:

D

E

E

80

MM irrelevance theorem- firm can use any mix of

debt and equity – this is unsatisfactory as a policy tool.

Searching for the Optimal Capital Structure.

-Tax benefits of debt.

-Asymmetric information- Signalling.

-Agency Costs (selfish managers).

-Debt Capacity and Risky Debt.

Optimal Capital Structure maximises firm value.

81

Combining Tax Relief and Debt Capacity (Traditional View).

K

V

D/E

82

D/E

3: Optimal Capital Structure, Agency

Costs, and Signalling.

Agency costs - manager’s self interested actions.

Signalling - related to managerial type.

Debt and Equity can affect Firm Value because:

- Debt increases managers’ share of equity.

-Debt has threat of bankruptcy if manager shirks.

- Debt can reduce free cashflow.

But- Debt - excessive risk taking.

83

AGENCY COST MODELS.

Jensen and Meckling (1976).

- self-interested manager - monetary rewards V private

benefits.

- issues debt and equity.

Issuing equity => lower share of firm’s profits for

manager => he takes more perks => firm value

Issuing debt => he owns more equity => he takes less

perks => firm value

84

Jensen and Meckling (1976)

V

V*

Slope = -1

A

V1

B1

B

If manager owns all of the equity, equilibrium point A.

85

Jensen and Meckling (1976)

V

V*

Slope = -1

A

B

V1

Slope = -1/2

B1

B

If manager owns all of the equity, equilibrium point A.

If manager owns half of the equity, he will got to point B if he

can.

86

Jensen and Meckling (1976)

V

V*

Slope = -1

A

B

V1

Slope = -1/2

V2

C

B1

B2

B

If manager owns all of the equity, equilibrium point A.

If manager owns half of the equity, he will got to point B if he

can.

Final equilibrium, point C: value V2, and private benefits B1.87

Jensen and Meckling - Numerical Example.

PROJECT

A

EXPECTED INCOME

500

MANAGER'S SHARE:

100%

VALUE OF PRIVATE

BENEFITS

TOTAL WEALTH

MANAGER'S SHARE:

50%

VALUE OF PRIVATE

BENEFITS

TOTAL WEALTH

PROJECT

B

1000

500

1000

800

500

1300

1500

250

500

800

500

1050

1000

Manager issues

100% Debt.

Chooses Project B.

Manager issues

some Debt and

Equity.

Chooses Project A.

Optimal Solution: Issue Debt?

88

Issuing debt increases the manager’s fractional

ownership => Firm value rises.

-But:

Debt and risk-shifting.

State 1

100

0

0.5

State 2

100

170

0.5

100

85

Debt

50

25

Equity

50

60

Values:

89

OPTIMAL CAPITAL STRUCTURE.

Trade-off: Increasing equity => excess perks.

Increasing debt => potential risk shifting.

Optimal Capital Structure => max firm value.

V

V*

D/E*

D/E

90

Other Agency Cost Reasons for Optimal Capital

structure.

Debt - bankruptcy threat - manager increases effort level.

(eg Hart, Dewatripont and Tirole).

Debt reduces free cashflow problem (eg Jensen 1986).

91

Agency Cost Models – continued.

Effort Level, Debt and bankruptcy (simple example).

Debtholders are hard- if not paid, firm becomes bankrupt, manager

loses job- manager does not like this.

Equity holders are soft.

Effort

Level

High

Low

Required

Funds

Income

500

100

200

What is Optimal Capital Structure (Value Maximising)?

92

Firm needs to raise 200, using debt and equity.

Manager only cares about keeping his job. He has a fixed

income, not affected by firm value.

a) If debt < 100, low effort. V = 100. Manager keeps job.

b) If debt > 100: low effort, V < D => bankruptcy.

Manager loses job.

So, high effort level => V = 500 > D. No bankruptcy =>

Manager keeps job.

High level of debt => high firm value.

However: trade-off: may be costs of having high debt

levels.

93

Free Cashflow Problem (Jensen 1986).

-Managers have (negative NPV) pet projects.

-Empire Building.

=> Firm Value reducing.

Free Cashflow- Cashflow in excess of that

required to fund all NPV projects.

Jensen- benefit of debt in reducing free cashflow.

94

Jensen’s evidence from the oil industry.

After 1973, oil industry generated large free cashflows.

Management wasted money on unnecessary R and D.

also started diversification programs outside the industry.

Evidence- McConnell and Muscerella (1986) – increases

in R and D caused decreases in stock price.

Retrenchment- cancellation or delay of ongoing projects.

Empire building Management resists retrenchment.

Takeovers or threat => increase in debt => reduction in

free cashflow => increased share price.

95

Jensen predicts:

young firms with lots of good (positive NPV) investment

opportunities should have low debt, high free cashflow.

Old stagnant firms with only negative NPV projects should

have high debt levels, low free cashflow.

Stultz (1990)- optimal level of debt => enough free

cashflow for good projects, but not too much free cashflow

for bad projects.

96

Income Rights and Control Rights.

Some researchers (Hart (1982) and (2001), Dewatripont and

Tirole (1985)) recognised that securities allocate income rights

and control rights.

Debtholders have a fixed first claim on the firm’s income, and

have liquidation rights.

Equityholders are residual claimants, and have voting rights.

Class discussion paper: Hart (2001)- What is the optimal

allocation of control and income rights between a single investor

and a manager?

How effective are control rights when there are different types of

investors?

Why do we observe different types of outside investors- what is

97

the optimal contract?

Conflict

Breaking MM

Benefits of Debt

Costs of Debt

Tax Relief

Fin’l Distress/

Debt Capacity

Agency Models

JM (1976)

Managerial

Perks

Increase Mgr’s

Ownership

Risk Shifting

Jensen (1986)

Empire Building

Reduce Freecash

Unspecified.

Stultz

Empire Building

Reduce Freecash

Underinvestment

.

Dewatripont and

Tirole, Hart.

Low Effort level

Bankruptcy threat

=>increased effort

DT- Inefficient

liquidations.

98

Signalling Models of Capital Structure

Assymetric info: Akerlof’s (1970) Lemons Market.

Akerlof showed that, under assymetric info, only bad things may be

traded.

His model- two car dealers: one good, one bad.

Market does not know which is which: 50/50 probability.

Good car (peach) is worth £2000. Bad car (lemon) is worth £1000.

Buyers only prepared to pay average price £1500.

But: Good seller not prepared to sell. Only bad car remains.

Price falls to £1000.

Myers-Majuf (1984) – “securities may be lemons too.”

99

Asymmetric information and Signalling Models.

- managers have inside info, capital structure has signalling

properties.

Ross (1977)

-manager’s compensation at the end of the period is

M (1 r ) 0 V 0 1V 1 if V 1 D

M (1 r ) 0 V 0 1V 1 C if V 1 D

D* = debt level where bad firm goes bankrupt.

Result: Good firm D > D*, Bad Firm D < D*.

Debt level D signals to investors whether the firm is good or bad.

100

Myers-Majluf (1984).

-managers know the true future cashflow.

They act in the interest of initial shareholders.

P = 0.5

Do

Nothing:

Issue

Equity

Good

Bad

Good

Assets

in Place

250

130

350

230

NPV of

new

project

Value of

Firm

0

0

20

10

250

130

370

240

Expected Value

190

305

New investors

0

100

Old Investors

190

205

Bad

101

Consider old shareholders wealth:

Good News + Do nothing = 250.

205

(370) 248.69.

Good News + Issue Equity =

305

Bad News and do nothing = 130.

Bad News and Issue equity =

205

(240) 161.31.

305

102

Old Shareholders’ payoffs

Good

News

Bad

News

Do

Issue

nothing and

invest

250 *

248.69

130

161.31*

Equilibrium

Good

News

Bad

News

Do

Issue

nothing and

invest

250 * 248.69

130

140 *

Issuing equity signals that the bad state will occur.

The market knows this - firm value falls.

Pecking Order Theory for Capital Structure => firms

prefer to raise funds in this order:

Retained Earnings/ Debt/ Equity.

103

Evidence on Capital structure and firm value.

Debt Issued - Value Increases.

Equity Issued- Value falls.

However, difficult to analyse, as these capital structure

changes may be accompanied by new investment.

More promising - Exchange offers or swaps.

Class discussion paper: Masulis (1980)- Highly

significant Announcement effects:

+7.6% for leverage increasing exchange offers.

-5.4% for leverage decreasing exchange offers.

104

Practical Methods employed by Companies (See

Damodaran; Campbell and Harvey).

-Trade off models: PV of debt and equity.

-Pecking order.

-Benchmarking.

-Life Cycle.

Increasing Debt?

time

105

Trade-off Versus Pecking Order.

• Empirical Tests.

• Multiple Regression analysis (firm size/growth

opportunities/tangibility of assets/profitability…..

• => Relationship between profitability and leverage

(debt): positive => trade-off.

• Or negative => Pecking order:

• Why?

• China: Reverse Pecking order

106

Capital Structure and Product

Market Competition.

• Research has recognised that firms’ financial

decisions and product market decisions not made

in isolation.

• How does competition in the product market affect

firms’ debt/equity decisions?

• Limited liability models: Debt softens

competition: higher comp => higher debt.

• Predation models: higher competition leads to

lower debt. (Why?)

107

Capital Structure and Takeovers

• Garvey and Hanka:

• Waves of takeovers in US in 1980’s/1990’s.

• Increase in hostile takeovers => increase in

debt as a defensive mechanism.

• Decrease in hostile takeovers => decrease in

debt as a defensive mechanism.

108

Garvey and Hanka (contiuned)

Trade-off: Tax shields/effort

levels/FCF/ efficiency/signalling

Vs financial distress

V

•

D/E

D/E*

109

Practical Capital Structure: case

study

•

110

Game Theoretic Approach to Capital

Structure.

• Moral Hazard Model.

• Asymmetric Information Model.

• See BCF section 8 for incorporation of

managerial overconfidence.

111

Cash-flow Rights and Control Rights

• Debt-holders: first fixed claim on cashflows (cash-flow rights); liquidation rights

in bas times (control rights)- hard investors.

• Equity-holders: residual claimants on cashflows (cash-flow rights): voting rights in

good times (control rights) – soft investors.

• => minority shareholder rights versus

blockholders.

112

Equity-holders’ control rights

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Voting rights.

Soft: free-rider problems.

Minority holders versus block-holders.

Minority –holders versus insiders.

Separation of ownership and control.

Corporate Charter.

Dual class of shares.

Pyramids/tunelling etc.

113

Capital/corporate structure in

emerging economies.

•

•

•

•

•

•

Separation of ownership and control.

Corporate Charter.

Dual class of shares.

Pyramids/tunelling etc.

Weak Legal Systems.

Cultural differences.

114

Game-theoretic approaches.

• JFE special issue 1988 (Grossman and Hart,

Stultz, Harris and Raviv).

• Bebchuk (lecture slides to follow).

• Garro Paulin and Fairchild (2006) Lecture

slides to follow.

115

Mergers and Acquisitions

116

Mergers and Acquisitions

•

•

•

•

Acquisitions

Divestitures

Restructuring

Corporate Governance

117

Growth Strategies

• Mergers: one economic unit formed from 2

or more previous units

• A) Tender offer

118

Merger

Acquisition

Stock

Acquisition

Takeovers

•

Proxy Contest

1. Merger- must be approved by stockholders’ votes.

2. Stock acquisition- No shareholder meeting, no vote required.

-bidder can deal directly with target’s shareholders- bypassing

target’s management.

- often hostile => target’s defensive mechanisms.

-shareholders may holdout- freerider problems.

3. Proxy Contests- group of shareholders try to vote in new

directors to the board.

119

Growth Strategies

• Mergers: one economic unit formed from 2

or more previous units

• A) Tender offer

• B) Pooling of Interest

• Joint Ventures

• Other collaborations (supplier networks,

alliances, investments, franchises)

120

Shrinkage strategies

•

•

•

•

Divestitures

Equity carveouts

Spin-offs

Tracking stock

121

Theories of M and A.

•

•

•

•

•

•

Efficiency increases (restructuring)

Operating Synergies

Financial Synergy

Information

Hubris and the Winner’s curse

Agency Problems (changes in

ownership/managerialism/FCF)

• Redistribution (tax, mkt power, …)

122

Synergy Value of a Merger

V AB (V A V B ).

Synergy comes from increases in cashflow form

the merger:

CFt REVt Costst

123

Example: Market Value after

Merger.

• Firm A (bidder): cashflows = £10m, r = 20%.

V = £50m.

• Firm B (target): cashflows = £6m, r = 15%.

=

£40m.

• If A acquires B: Combined Cashflows are

expected to increase to £25m P.A. New Discount

rate 25%.

• Synergy cashflows = £9m.

• Total value = £100m.

• Synergy Value = £10m.

124

Who gets the gains from mergers?

•

Depends on what the bidder has to pay!

(bid premium)

NPVBidder VAB VA I

NPVt arg et I VB

If

I VB , Bidder gets all of the positive NPV.

If

I VAB VA ,

Target gets all of the positive NPV.

125

Why a Bid premium?

• Hostile Bid: defensive (anti-takeover)

mechanisms (leverage increases, poison

pills, etc):

• Bidding wars.

• Market expectations.

126

Effects of takeovers on stock prices of bidder

and target.

Successful Bids

Unsuccessful Bids

Takeover Target

Technique

Tender

30%

Offer

Merger

20%

Bidders

Proxy

Contest

n.a

•

8%

4%

0

Takeover Target

Technique

Tender

-3%

Offer

Merger

-3%

Bidders

Proxy

Contest

n.a

8%

-1%

-5%

Jensen and Ruback JFE 1983

127

Game Theoretic Approach to M and A.

• Grossman and Hart (Special Issue on Corporate

Control 1982).

• Harris and Raviv (Special Issue on Corporate

Control 1982).

• Bebchuk (Special Issue on Corporate Control

1982)..

• Burkart (JOF 1995).

• Garvey and Hanka.

• Krause.

128

Garvey and Hanka paper

• Lecture slides to follow.

129

Grossman and Hart free-rider paper

• Lecture slides to follow.

130

Convertible Debt

•

•

•

•

•

-Valuation of Convertibles.

-Impact on Firm Value.

-Why firms issue convertibles.

-When are they converted (call policy)?

Convertible bond -holder has the right to

exchange the bond for common stock (equivalent

to a call option).

• Conversion Ratio = number of shares received

for each bond.

• Value of Convertible Bond = Max{ Straight bond

131

value, Conversion Value} +option value.

Value of Convertible Bond.

V

Face

Value

Straight Bond Value

Conversion Value

•

Firm Value

Firm Value

Total Value of Convertible Bond

Firm Value

132

• Conflict between Convertible Bond holders and

managers.

• Convertible Bond = straight debt + call option.

• Value of a call option increases with:

• Time.

• Risk of firm’s cashflows.

• Implications: Holders of convertible debt

maximise value by not converting until forced to

do so => Managers will want to force conversion

as soon as possible.

• Incentive for holders to choose risky projects =>

managers want to choose safe projects.

133

Reasons for Issuing Convertible Debt.

Much real world confusion.

Convertible debt - lower interest rates than straight debt.

=> •Cheap form of financing?

No! Holders are prepared to accept a lower interest rate because

of their conversion privilege.

N

IC

PR

.

t

N

(1 K C )

t 1 (1 K C )

CD = N

ID

M

.

t

N

D = t 1 (1 K D ) (1 K D )

I D I C , PR M , K D KC CD D.

134

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Example of Valuation of Convertible Bond.

October 1996: Company X issued Convertible Bonds at

October 1996: Coupon Rate 3.25%, Each bond had face

Value £1000.

Bonds to mature October 2001.

Convertible into 21.70 Shares per per bond until October

2001.

Company rated A-. Straight bonds would yield 5.80%.

Now October 1998:

Face Value £1.1 billion.

Convertible Bonds trading at £1255 per bond.

The value of the convertible has two components; The

straight bond value + Value of Option.

135

Valuation of Convertible Bond- Continued.

If the bonds had been straight bonds: Straight bond value =

PV of bond =

•

t 3

16.25

1000

932.83

t

3

(1.058)

t 0.5 (1.058)

Price of convertible = 1255.

Conversion Option = 1255 – 933 = 322.

Oct 1998 Value of Convertible = 933 + 322 = 1255.

= Straight Bond Value + Conversion Option.

136

Alternative Analysis of Irrelevance of Convertible Debt.

Firm Does

Badly.

•

Firm Does

Well.

Convertible Debt.No Conversion. Conversion.

Compared with: CD cheaper

CD expensive,

Straight Bonds. financing, lower Bonds are

coupon rate.

converted,

Existing Equity

Dilution.

Equity.

CD expensive. CDs cheaper.

Firm Indifferent between issuing CD, debt or equity.

-MM.

137

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Why do firms issue convertible debt?

If convertible debt is not a cheap form of financing, why is it

issued?

A. Equity through the Back Door (Stein, Mayers).

-solves asymmetric information problems (see MyersMajluf).

-solves free cashflow problems.

B. Convertible debt can solve risk-shifting problems.

- If firm issues straight debt and equity, equity holders have

an incentive to go for risky (value reducing) NPV projects.

Since CD contains an option feature, CD value increases with

risk.

-prevents equity holders’ risk shifting.

138

Convertible Debt and Call Policy.

Callable Convertible debt =>firms can force conversion.

When

• the bond is called, the holder has 30 days to either:

a) Convert the bond into common stock at the conversion

ratio, or

b) Surrender the bond for the call price.

When should the bond be called?

Option Theory: Shareholder wealth is maximised/ CD holders

wealth is minimised if

Firm calls the bond as soon as value = call price.

139

• Call Puzzle.

• Manager should call the bond as soon as he can force

conversion.

• Ingersoll (1977) examined the call policies of 124

firms 1968-1975.

• - He found that companies delayed calling far too

long.

• - median company waited until conversion value was

44% above call price - suboptimal.

• Call Puzzle addressed by Harris and Raviv.

• - signalling reasons for delaying calling.

• - early calling might signal bad news to the market.

140

4: Dividend Policy

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Miller-Modigliani Irrelevance.

Gordon Growth (trade-off).

Signalling Models.

Agency Models.

Lintner Smoothing.

Dividends versus share repurchases.

Empirical examples

141

Early Approach.

• Three Schools of Thought• Dividends are irrelevant (MM).

• Dividends => increase in stock prices

(signalling/agency problems).

• Dividends => decrease in Stock Prices (negative

signal: non +ve NPV projects left?).

• 2 major hypotheses: Free-cash flow versus

signalling

142

Important terminology

• Cum Div: Share price just before dividend

is paid.

• Ex div: share price after dividend is paid <

Cum div.

P

CD

ED

CD

CD

ED

ED

Time

143

Example

• A firm is expecting to provide dividends every

year-end forever of £10. The cost of equity is

10%.

• We are at year-end, and div is about to be paid.

Current market value of equity = 10/0.1 + 10 =

£110

• Div is paid. Now, current market value is

• V = 10/0.1 = £100.

• So on…

144

P

•

CD =

110

ED = 100

CD

CD

ED

ED

Time

145

Common Stock Valuation Model

• You are considering buying a share at price Po,

and expect to hold it one year before selling it

ex-dividend at price P1: cost of equity = r.

d1

P1

P0

(1 r ) (1 r )

What would the buyer be prepared to pay to you?

d2

P2

P1

(1 r ) (1 r )

146

Therefore:

d1

d2

p2

P0

2

2

1 r (1 r ) (1 r )

Continuing this process, and re-substituting in

(try it!), we obtain:

d1

p0 t 1

(1 r )t

Price today is discounted value of all future dividends to

infinity (fundamental value = market value).

147

Dividend Irrelevance (MillerModigliani)

• MM consider conditions under which

dividends are irrelevant.

• Investors care about both dividends and

capital gains.

• Perfect capital markets:• No distorting taxes

• No transactions costs.

• No agency costs or assymetric info.

148

Dividend Irrelevance (MM):

continued

• Intuition: Investors care about total return

(dividends plus capital gains).

• Homemade leverage argument

• Source and application of funds argument

=> MM assumed an optimal investment

schedule over time (ie firm invests in all

+ve NPV projects each year).

149

Deriving MM’s dividend irrelevance

• Total market value of our all-equity firm is

•

Dt

S0 t 1

t

(1 r )

T

Sources = Uses

CFt Ft Dt I t (1 r ) Ft 1

150

Re-arranging:

Dt CFt Ft I t (1 r ) Ft 1

Substitute into first equation:

CF1 F1 I1 (1 r ) F0

T

S0 CF0 F0 I 0 (1 r ) F1

t 2 ...

(1 r )

At t =0,

CF0 F1 0

S0 F0 I 0

CF1 F1 I1 (1 r ) F0

T

t 2 ...

(1 r )

151

Successive substitutions

(CFt I t )

S 0 t 0

(1 r ) t

T

•Current value of all-equity firm is present value of operating

cashflows less re-investment for all the years (residual

cashflow available to shareholders) Dividends do not appear!

•Assn: firms make optimal investments each period (firm

invests in all +ve NPV projects).

•Firms ‘balance’ divs and equity each period: divs higher

than residual cashflow => issue shares.

•Divs lower than free cashflow: repurchase shares.

152

Irrelevance of MM irrelevance

(Deangelo and Deangelo)

• MM irrelevance based on the idea that all

cash will be paid as dividend in the end (at

time T).

• Deangelo argues that even under PCM, MM

irrelevance can break down if firm never

pays dividend!

153

Irrelevance of MM irrelevance

(continued)

• Consider an all-equity firm that is expected to produce

residual cashflows of £10 per year for 5 years.

• Cost of equity 10%.

• First scenario: firm pays no dividends for the first 4 years.

Pays all of the cashflows as dividends in year 5.

10

V0 t 1

?

t

(1.1)

5

• Now it is expected to pay none of the cashflows in any year:

Vo = 0 !

154

“Breaking” MM’s Irrelevance

•

•

•

•

•

MM dividend irrelevance theorem based on:

PCM

No taxes

No transaction costs

No agency or asymmetric information

problems.

155

Gordon Growth Model.

• MM assumed firms made optimal investments out

of current cashflows each year

• Pay any divs it likes/ balanced with new

equity/repurchases.

• What if information problems etc prevent firms

easliy going back to capital markets:

• Now, real trade-off between investment and

dividends?

156

Gordon Growth Model.

Where does growth come from?- retaining

cashflow to re-invest.

Constant fraction, K, of earnings retained for reinvestment.

Rest paid out as dividend.

Average rate of return on equity = r.

Growth rate in cashflows (and dividends) is g = Kr.

Div 0

Div 1

NCF 0 (1 Kr )(1 K )

.

V0

g g

Kr

157

Example of Gordon Growth Model.

£K

19x5

Profits After Tax (NCF)

Retained Profit (NCF.K)

19x6

19x7

19x8

19x9

Average

2500

1550

2760

1775

2635

1600

2900

1800

3100

1900

950

985

1035

1100

1200

Share Capital + retentions

B/F

C/F (= BF + Retained Profit)

30000

31550

31550

33325

33325

34925

34925

36725

36725

38625

Retention Rate K

r on opening capital

0.62

0.083

0.64

0.087

0.61

0.079

0.62

0.083

0.61

0.084

Dividend (NCF(1-K))

0.62

0.083

g = Kr = 0.05.

How do we use this past data for valuation?

158

Gordon Growth Model (Infinite Constant

Growth Model).

Let

12%

Div 0 (1 g ) Div1 1200(1.05)

1260

V0

g

g

g

0.12 0.05

= 18000

159

Finite Supernormal Growth.

-Rate of return on Investment > market required return for T

years.

-After that, Rate of Return on Investment = Market required

return.

V0

NCF1

(r )

K . NCF1.T

(1 )

If T = 0, V = Value of assets in place (re-investment at zero

NPV).

Same if r = .

160

Examples of Finite Supernormal Growth.

NCF1 100.

10%.

T = 10 years. K = 0.1.

A. Rate of return, r = 12% for 10 years,then 10% thereafter.

100

(0.12 0.1)

V0

0.1.(100).10

1018

0.1

0.1(1 0.1)

B. Rate of return, r = 5% for 10 years,then 10% thereafter.

100

(0.05 0.1)

V0

0.1.(100).10

955

0.1

0.1(1 0.1)

161

Dividend Smoothing V optimal

re-investment (Fairchild 2003)

• Method:• GG Model: derive optimal retention/payout

ratio

• => deterministic time path for dividends,

Net income, firm values.

• => Stochastic time path for net income: how

can we smooth dividends (see Lintner

smoothing later….)

162

Deterministic Dividend Policy.

Div

N

1

0 (1 K )(1 Kr )

.

• Recall V 0

g

Kr

•

• Solving V0

0,

K

• We obtain optimal retention ratio

•

K*

( r )( 1)

r

.

163

Analysis of K *

• If r [0, 1 ],

K* 0.

K

*

], K * [0,1], with

• If r [0,

0.

1

r

• Constant r over time => Constant K* over

time.

164

Deterministic Case (Continued).

• Recursive solution:

Dt N 0 (1 K *)(1 K * r )

t

• => signalling equilibria.

• Shorter horizon => higher dividends.

When r is constant over time, K* is constant. Net

Income, Dividends, and firm value evolve

deterministically.

165

Stochastic dividend policy.

• Future returns on equity normally and

independently distributed, mean r.

• Each period, K* is as given previously.

• Dividends volatile.

• But signalling concerns: smooth dividends.

• => “buffer” from retained earnings.

166

Agency problems

• Conflicts between shareholders and

debtholders: risk-shifting: high versus low

dividends => high divs => credit rating of

debt

• Conflicts between managers and

shareholders: Jensen’s FCF, Easterbrook.

167

Are Dividends Irrelevant?

- Evidence: higher dividends => higher value.

- Dividend irrelevance : freely available capital for reinvestment. If too much dividend, firm issued new shares.

- If capital not freely available, dividend policy may matter.

C. Dividend Signalling - Miller and Rock (1985).

NCF + NS = I + DIV: Source = Uses.

DIV - NS = NCF - I.

Right hand side = retained earnings. Left hand side higher dividends can be covered by new shares.

168

Div - NS - E (Div - NS) = NCF - I - E (NCF - I)

= NCF - E ( NCF).

Unexpected dividend increase - favourable signal of NCF.

Prob

0.5

Firm A

0.5

Firm B

E(V)

NCF

400

1400

900

New Investment

600

600

600

Dividend

New shares

0

200

800

0

400

100

E(Div - NS) = E(NCF - I) = 300.

Date 1 Realisation: Firm B: Div - NS - E (Div - NS) = 500 = NCF - E

( NCF).

Firm A : Div - NS - E (Div - NS) = -500 = NCF - E ( NCF).

169

Dividend Signalling Models.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Bhattacharya (1979)

John and Williams (1985)

Miller and Rock (1985)

Ofer and Thakor (1987)

Fuller and Thakor (2002).

Fairchild (2009/10).

Divs credible costly signals: Taxes or borrowing costs.

170

Competing Hypotheses.

• Dividend Signalling hypothesis Versus Free

Cashflow hypothesis.

• Fuller and Thakor (2002; 2008): Consider

asymmetric info model of 3 firms (good, medium,

bad) that have negative NPV project available

• Divs used as a) a positive signal of income, and b)

a commitment not to take –ve NPV project

(Jensen’s FCF argument).

• Both signals in the same direction (both +ve)

171

Signalling, FCF, and Dividends.

Fuller and Thakor (2002)

• Signalling Versus FCF hypotheses.

• Both say high dividends => high firm value

• FT derive a non-monotonic relationship

between firm quality and dividends.

Divs

Firm

Quality

172

Fairchild (2009, 2010)

• Signalling Versus FCF hypotheses.

• But, in contrast to Fuller and Thakor, I

consider +ve NPV project.

• Real conflict between high divs to signal

current income, and low divs to take new

project.

• Communication to market/reputation.

173

Cohen and Yagil

• New agency cost: firms refusing to cut

dividends to invest in +ve NPV projects.

• Wooldridge and Ghosh

• 6 roundtable discussions of CF.

174

Agency Models.

•

•

•

•

Jensen’s Free Cash Flow (1986).

Stultz’s Free Cash Flow Model (1990).

Easterbrook.

Fairchild (2009/10): Signalling + moral

hazard.

175

Behavioural Explanation for

dividends

• Self-control.

• Investors more disciplined with dividend

income than capital gains.

• Mental accounting.

• Case study from Shefrin.

• Boyesen case study.

176

D.

Lintner Model.

Managers do not like big changes in dividend (signalling).

They smooth them - slow adjustment towards target payout rate.

Div t Div t 1 K .(T . epst Div t 1)

K is the adjustment rate. T is the target payout rate.

FIRM

K

EPS

Dividend Policy -Lintner Model

YEAR

50.00

A

B

0.5

DIV

C

0

DIV

1

DIV

Values

40.00

30.00

20.00

10.00

0.00

1

2

3

4

5

Years

6

7

8

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

30.00

34.00

28.00

25.00

29.00

33.00

36.00

40.00

13.25

15.13

14.56

13.53

14.02

15.26

16.63

18.31

11.50

11.50

11.50

11.50

11.50

11.50

11.50

11.50

15.00

17.00

14.00

12.50

14.50

16.50

18.00

20.00

177

Using Dividend Data to analyse Lintner Model.

Div t (1 K ) Div t 1 K .T . epst .

In Excel, run the following regression;

Div t a bDiv t 1 cEpst

The parameters give us the following information,

a = 0, K = 1 – b, T = c/ (1 – b).

178

Dividends and earnings.

• Relationship between dividends, past,

current and future earnings.

• Regression analysis/categorical analysis.

179

Dividends V Share Repurchases.

• Both are payout methods.

• If both provide similar signals, mkt reaction

should be same.

• => mgrs should be indifferent between

dividends and repurchases.

180

Dividend/share repurchase

irrelevance

• Misconception (among practitioners) that

share repurchasing can ‘create’ value by

spreading earnings over fewer shares

(Kennon).

• Impossible in perfect world:

• Fairchild (JAF).

181

Dividend/share repurchase

irrelevance (continued)

• Fairchild: JAF (2006):

• => popular practitioner’s website argues

share repurchases can create value for nontendering shareholders.

• Basic argument: existing cashflows/assets

spread over fewer shares => P !!!

• Financial Alchemy !!!

182

The Example:….

•

•

•

•

•

•

Kennon (2005): Eggshell Candies Inc

Mkt value of equity = $5,000,000.

100, 000 shares outstanding

=> Price per share = $50.

Profit this year = £1,000,000.

Mgt upset: same amount of candy sold this

year as last: growth rate 0% !!!

183

Eggshell example (continued)

• Executives want to do something to make

shareholders money after the disappointing

operating performance:

• => One suggests a share buyback.

• The others immediately agree !

• Company will use this year’s £1,000,000

profit to but stock in itself.

184

Eggshell example (continued)

• $1m dollars used to buy 20,000 shares (at

$50 per share). Shares destroyed.

• => 80,000 shares remain.

• Kennon argues that, instead of each share

being 0.001% (1/100,000) of the firm, it is

now .00125% of the company (1/80)

• You wake up to find that P from $50 to

$62.50. Magic!

185

Kennon quote

• “When a company reduces the amount of

shares outstanding, each of your shares

becomes more valuable and represents a

greater % of equity in the company … It is

possible that someday there may be only 5

shares of the company, each worth one

million dollars.”

• Fallacy! CF: no such thing as a free lunch!

186

MM Irrelevance applied to Eggshell

example

At beginning of date 0:

N 0 (1 g )

V0

g

At end of date 0, with N0 just achieved, but still in the

business (not yet paid out as dividends or repurchases:

N1 (1 g )

V0 N 0

g

187

Eggshell figures

N1 (1 g )

1,000,000

V0 N 0

1,000,000

5,000,000

g

0.25

Cost of equity will not change: only way to increase value

per share is to improve company’s operating performance, or

invest in new positive NPV project. Repurchasing shares is a

zero NPV proposition (in a PCM).

Eggshell has to use the $1,000,000 profit to but the shares.

188

Eggshell irrelevance (continued)

• Assume company has a new one-year zero

NPV project available at the end of date 0.

• 1. Use the profit to Invest in the project.

• 2. Use the profit to pay dividends, or:

• 3. Use the profit to repurchase shares.

189

Eggshell (continued)

1,000,000

5,000,000 P $50

0.25

1.

V0 1,000,000

2.

1,000,000

V0

4,000,000 P $40

0.25

Ex div

Each year –end: cum div = $50, ex div = $40

3.

1,000,000

V0

4,000,000 P $50

0.25

190

Long-term effects of repurchase

• See tables in paper:

• Share value pre-repurchase = $5,000,000 each

year.

• Share value-post repurchase each year =

$4,000,000

• Since number of shares reducing, P .by 25%, but

this equals cost of equity.

• And is same as investing in zero NPV project.

191

Conclusion of analysis

• In PCM, share repurchasing cannot increase share

price (above a zero NPV investment) by merely

spreading cashflows over smaller number of

shares.

• Further, if passing up positive NPV to repurchase,

not optimal!

• Asymmetric info: repurchases => positive signals.

• Agency problems: FCF.

• Market timing.

• Capital structure motives.

192

Dividend/share repurchase

irrelevance

• See Fairchild (JAF 2005)

• Kennon’s website

193

Evidence.

• Mgrs think divs reveal more info than

repurchases (see Graham and Harvey

“Payout policy”.

• Mgrs smooth dividends/repurchases are

volatile.

• Dividends paid out of permanent

cashflow/repurchases out of temporary

cashflow.

194

Motives for repurchases

(Wansley et al, FM: 1989).

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Dividend substitution hypothesis.

Tax motives.

Capital structure motives.

Free cash flow hypothesis.

Signalling/price support.

Timing.

Catering.

195

Repurchase signalling.

• Price Support hypothesis: Repurchases

signal undervaluation (as in dividends).

• But do repurchases provide the same signals

as dividends?

196

Repurchase signalling:

(Chowdhury and Nanda Model: RFS 1994)

• Free-cash flow => distribution as

commitment.

• Dividends have tax disadvantage.

• Repurchases lead to large price increase.

• So, firms use repurchases only when

sufficient undervaluation.

197

Open market Stock Repurchase

Signalling:

McNally, 1999

• Signalling Model of OM repurchases.

• Effect on insiders’ utility.

• If do not repurchase, RA insiders exposed to

more risk.

• => Repurchase signals:

• a) Higher earnings and higher risk,

• b) Higher equity stake => higher earnings.

198

Repurchase Signalling :

Isagawa FR 2000

• Asymmetric information over mgr’s private

benefits.

• Repurchase announcement reveals this info

when project is –ve NPV.

• Repurchase announcement is a credible

signal, even though not a commitment.

199

Costless Versus Costly Signalling:

Bhattacharya and Dittmar 2003

• Repurchase announcement is not

commitment.

• Costly signal: Actual repurchase: separation

of good and bad firm.

• Costless (cheap-talk): Announcement

without repurchasing. Draws analysts’

attention.

• Only good firm will want this

200

Repurchase timing

• Evidence: repurchase timing (buying shares

cheaply.

• But market must be inefficient, or investors

irrational.

• Isagawa.

• Fairchild and Zhang.

201

Repurchases and irrational

investors.

Isagawa 2002

• Timing (wealth-transfer) model.

• Unable to time market in efficient market

with rational investors.

• Assumes irrational investors => market

does not fully react.

• Incentive to time market.

• Predicts long-run abnormal returns postannouncement.

202

Repurchase Catering.

• Baker and Wurgler: dividend catering

• Fairchild and Zhang: dividend/repurchase

catering, or re-investment in positive NPV

project.

203

Competing Frictions Model:

From Lease et al:

Taxes

•

Low

Payout

Low Payout

Agency

Costs

High

Payout

High Payout

Asymmetric

Information

High

Low Payout

Payout

204

Dividend Cuts bad news?

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Fairchild’s 2009/10 article.

Wooldridge and Ghosh:=>

ITT/ Gould

Right way and wrong way to cut dividends.

Other cases from Fairchild’s article.

Signalling/FCF hypothesis.

FCF: agency cost: cutting div to take –ve NPV project.

New agency cost: Project foregone to pay high dividends.

Communication/reputation important!!

205

Venture Capital/private

equity/Hedge Funds

• Venture capitalists typically supply start-up

finance for new entrepreneurs.

• VC’s objective; help to develop the venture over 5

– 7 years, take the firm to IPO, and make large

capital gains on their investment.

• In contrast, private equity firms invest in later

stage public companies to a) take them private:

Turnarouds, or b) Growth capital.

• Hedge Funds: Privately-owned institutions that

invest in Financial markets using a variety of

strategies.

206

Hedge Funds

• Privately-owned institutions

• Limited range of High net worth (wealthy)

investors => HF => invests in FMs

• Each fund has its own investment strategy

• Largely unregulated (in contrast to mutual

funds); => debate.

207

HF strategies

• HF mgr typically commits to a strategy, using

following elements

• Style

• Market

• Instrument

• Exposure

• Sector

• Method

• Diversification

208

HF Strategies (continued)

• Style: Global Macro, directional, event driven….

• Market: equity, fixed income, commodity,

currency

• Instrument: long/short, futures, options, swaps

• Exposure: directional, market neutral

• Sector: emerging markets, technology, healthcare

• Method: Discretionary/qualitative (mgr selects

investments): systematic/quantitative (quants)

209

Leverage:

• HFs are marketed on the promise of making

‘absolute returns’ regardless of mkt

• May involve hedging (long-short) plus high

levels of leverage

• => very risky?

• Risk-shifting incentives made worse by HF

mgr fee structure!

210

HF fee structure

• Asymmetric fees (in mutual fund,

symmetric or fulcrum fees).

• HF mgr gets a percentage of assets under

management plus a performance bonus on

the upside: no loss on the downside

(investor loses there!)

• => systemic risk? Regulation debate.

211

Fairchild and Puri (2011)

• Brand new paper on SSRN!

• HF mgr/ Investor negotiate (bargain) over form of

contract: asymmetric or symmetric)

• HF mgr then chooses safe or risky strategy.

• He then exerts effort in trying to make strategy

succeed.

• Paper looks at effects of BP and incetnives on

contract, strategy and HF performance and risk!

212

Activist HFs

• Passive HFs just invest in FMs, an d look at

portfolio decisions

• Activist HFs actually get involved in the

companies that they invest in

• Members on the board

• Assist/interfere in mgt decisions

• Debate: do they add or destroy value?

• Myopic?

213

Private Equity.

• PE firms generally buy poorly performing

publically listed firms.

• Take them private

• Improve them (turn them around).

• Hope to float them again for large gains

• Theory of private equity turnarounds” plus

PE leverage article, plus economics of PE

articles.

214

Theory of PE-turnarounds (Cuny and

Talmor JCF 2007)

• Explores advantage of PE in fixing

turnaround

• Would poorly performing mgrs want to

involve PEs when they may lose their jobs?

215

Venture capitalists

• Venture capitalists provide finance to start-up

entrepreneurs

• New, innovative, risky, no track-record…

• Hence, these Es have difficulty obtaining finance

from banks or stock market

• VCs more than just investors

• Provide ‘value-adding’ services/effort

• Double-sided moral hazard/Adverse selection

216

Venture capital process

• Investment appraisal stage: seeking out good

entrepreneurs/business plans: VC overconfidence?

• Financial contracting stage: negotiate over

cashflow rights and control rights.

• Performance stage: both E and VC exert valueadding effort: double-sided moral hazard.

• Ex post hold-up/renegotiation stage? Double

sided moral hazard

• => exit: IPO/trade sale => capital gains (IRR)

217

VC process (continued)

• VCs invest for 5-7 years.

• VCs invest in a portfolio of companies: anticipate

that some will be highly successful, some will not

• Value-adding? Visit companies, help them

operationally, marketing etc.

• Empirical evidence on hours/year spent at each

company

• => attention model of Gifford.

218

Venture Capital Financing

•

•

•

•

Active Value-adding Investors.

Double-sided Moral Hazard problem.

Asymmetric Information.

Negotiations over Cashflows and Control

Rights.

• Staged Financing

• Remarkable variation in contracts.

219

Features of VC financing.

• Bargain with mgrs over financial contract

(cash flow rights and control rights)

• VC’s active investors: provide value-added

services.

• Reputation (VCs are repeat players).

• Double-sided moral hazard.

• Double-sided adverse selection.

220

Kaplan and Stromberg

• Empirical analysis, related to financial

contract theories.

221

Financial Contracts.

•

•

•

•

Debt and equity.

Extensive use of Convertibles.

Staged Financing.

Control rights (eg board control/voting

rights).

• Exit strategies well-defined.

222

Game-theoretic models of Venture

Capitalist/entrepreneur contracting

• Double-sided moral hazard models (ex ante

effort/ ex post holdup/renegotiation/stealing) – self-interest

• Behavioural Models (Procedural justice,

fairness, trust, empathy)

223

Fairchild (JFR 2004)

• Analyses effects of bargaining power,

reputation, exit strategies and value-adding

on financial contract and performance.

• 1 mgr and 2 types of VC.

• Success Probability depends on effort:

P eM i eVC

where

i {0,1},

=> VC’s valueadding.

224

Fairchild’s (2004) Timeline

• Date 0: Bidding Game: VC’s bid to supply

finance.

• Date 1: Bargaining game: VC/E bargain

over financial contract (equity stakes).

• Date 2: Investment/effort level stage.

• Date 3: Renegotiation stage: hold-up

problems

• Date 4: Payoffs occur.

225

Bargaining stage

• Ex ante Project Value

V PR (1 P).0 PR.

• Payoffs:

2

em

S M PR

.

2

2

eVC

SVC (1 ) PR

.

2

226

Optimal effort levels for given

equity stake:

•

em * ,

(1 )

eVC *

.

227

Optimal equity proposals.

• Found by substituting optimal efforts into

payoffs and maximising.

• Depends on relative bargaining power, VC’s

value-adding ability, and reputation effect.

• Eg; E may take all of the equity.

• VC may take half of the equity.

228

Payoffs

0

Dumb VC!

E

VC

0.5

Equity Stake

229

Tykvova’s review paper of VC

• Problem is: more equity E has, less equity

VC has: affects balance of incentives.

• Problem for VC is giving enough equity to

motivate E, while keeping enough for

herself

230

Ex post hold-up problem

• In Fairchild (2004): VC can force

renegotiation of equity stakes in her favour

after both players have exerted effort.

• She takes all of the equity

• How will this affect rational E’s effort

decision in the first place?

231

E’s choice of financier

•

•

•

•

Growing research on E’s choice of financier

VC versus banks

VC versus angels