10/06/05 lecture

advertisement

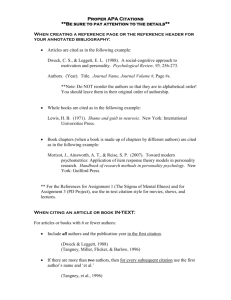

How to Read a Technical Paper Locking and Consistency 10/7/05 Two goals for today J.N. Gray, R.A. Lorie, G.R. Putzolu, I.L. Traiger, “Granularity of Locks and Degrees of Consistency in a Shared Database”, in Hellerstein and Stonebraker (Eds), Readings in Database Systems, 4/e, MIT Press:Cambridge MA, 0-262-69314-3, 2005. How to read a technical paper (and by example, how to write one), using Gray, et al as our concrete exemplar. An initial understanding of the basic content of Gray, et al. What kind of readings are there? (1/3) Quick sample, approximately 5 minutes, used: to decide if the paper is worth further effort to note citation for possible future literature review/background survey, I.e., to discover the relation of this paper to your own research. What kind of readings are there? (2/3) Cursory (aka “first reading”), depending on length 0.5 to 2.0 hour, used: To discover the problem solved, approximately, the solution, and whether or not you’ll do an in depth reading. To discover the impact this paper has on your work and, more importantly, vice versa! A cursory reading will cover between 75 and 100% of the paper. What kind of readings are there? (3/3) Careful (aka “in depth”, aka “detailed”), depending on how much material, could be 0.5 to 6.0 hours: To understand, as well as the authors do, the contribution of all or part of the paper. A more accurate understanding of how this paper relates to your own work. A careful reading will often cover 25-50% of a paper, but may occasionally go as high as 100% and, very occasionally go lower. In your journal - during the Quick Sampling Citation 1 sentence description that you compose after your first sampling. Your initial opinion of the relevance and/or caliber. Get yourself oriented before starting.(1/3) What kind of paper is this? Estimate the time required for the first reading. Experimental vs Conceptual GLPT --> conceptual Look at number of pages, number of figures, density of text, etc. Understand the title. Get yourself oriented before starting (2/3) Note authors’ names and affiliations. In computer science, the authors will be ordered in one of the following: • By contribution to the research • Alphabetically (usually means equal collaboration) • Lead author first, followed by alphabetical or level of contribution. Get yourself oriented before starting. (3/3) Note caliber of references and how citations are made. In early days, few references are common. Now, expect between 5 and 20 papers referenced for a good quality paper. “Caliber” refers to where/when published, how much authors reference their own work, peer-reviewed, technical report versus conference versus journal. Cursory reading (1/2) The goal is to discover the problem solved, approximately the solution, and how you think this paper relates to your own work. Read every word of the abstract. The abstract gives a “long distance” view. The authors use the abstract to tell the reader what is in the paper and why he should read it. While you read the paper, make an outline that corresponds to the paper’s structure. Cursory reading (2/2) If there is an introduction, skim the first and last (and sometimes the penultimate) paragraphs. If there is a conclusion, skim the entire conclusion, reading the first and last paragraphs carefully. Skim through the rest of the paper. Make your journal entry description more accurate -- this is what you go back to when you write your own paper. Detailed reading Focus in on the particular areas you are interested in. Read them as though you’re reading a textbook! Make annotations in the margins Try to understand, in detail, what is being said. Write down, in the margins, possible future research topics (“the authors said ‘x’, but what if I were to try ‘y’? “) Work through their examples and make up your own. Detailed reading There will be too much information from a detailed reading to record in your journal. So either: Place a copy in a binder with your notes on the paper, or Place your notes in a binder with complete citation (so you can find this work again). Web and other transient work For transient items, If the paper is worthy of a detailed reading, it is INCUMBENT upon you to make a hard copy of the paper. If the paper is not worthy of a detailed reading, you won’t be citing it in any of your work. Keep the reference in your journal, but you won’t actually be using it. If the paper cannot be referenced by readers of your work for (at least) 5 years, you may not cite it (worthy or not). Web and other transient work Some Web sites are very stable -- e.g., major universities (UM, CMU, Caltech, CMU, …), professional organizations (ACM, IEEE, …). Papers published on those sites can be cited by you, and you don’t need a hard copy. How to use a paper in your work (1/2) You’ll see the style of citation that is expected by the publisher. [1], [2], … in order of appearance in the paper is tough to modify while you’re editing your paper. [1], [2], alphabetized by first author, is also tough to maintain. I like an alphabetized list of strings, e.g., for this paper I would use the string [GLPT76]. In the references section, these would be given in lexical order. How to use a paper in your work (2/2) The best way to learn how to do this is by observation. Frequently there is a literature review section that groups related, cited work together with a brief statement on how they relate to your work. Frequently your work is specifically related to a cited work, as in p 258’s reference to [1]. End of “how to read a paper”