Pediatric Advanced Life Support

advertisement

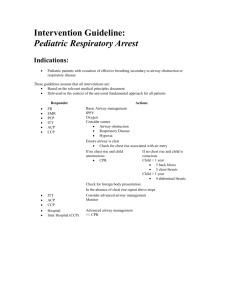

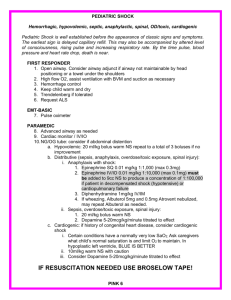

Pediatric Advanced Life Support Agenda DAY 1 Course introductions and overview Review new 2011 updates BLS primary survey video PALS secondary survey video CPR and AED practice, ETCO2 monitoring (group 1) Airway devices and intubation (group 2) Bradycardia station (group 1) Asystole/PEA station (group2) Patient assessment Video Respiratory emergencies (group 1) VF/VT station (group 2) DAY 2 Tachycardias Shocks Lead II rhythm review Team resuscitation concept video Algorithm review Mega-code review/practice Testing and Megacode Remediation Introduction PALS is designed to give the learner the ability to assess and quickly respond to pediatric emergencies including respiratory arrest and cardiac arrest. The course is two days and encompasses a written exam and a core scenario that must be passed with at least an 84%. First hour of class we will be going over a pre-test. PALS Over View: AHA guidelines Purpose of PALS Acquire the ability to recognize an infant or child whom requires advanced life support Learn to apply the “Assess, Categorize, Decide and Act” model of assessment Learn the importance and technique for quality and effective CPR and advanced life support Learn effective team coordination and team member roles in resuscitation Key Points of Importance of PALS The first step in cardiac arrest is prevention If cardiac arrest does occur, effective high quality CPR is the most important aspect in successful resuscitation Studies show that poor skills by healthcare workers lead to increased incidences of death and brain death All PALS students must perform effective and quality CPR throughout the course WATCH PALS INTRODUCTION ON VIDEO *NEW 2011 CPR UPDATE CHANGES: BLS If there's a palpable pulse >60, but the patient shows inadequate breathing, give rescue breaths at a rate of 12–20 breaths/minute (one breath every three to five seconds) using the higher rate for younger children If the pulse is <60 and there are signs of poor perfusion (pallor, mottling, cyanosis) despite support of oxygenation and ventilation, begin chest compressions. Beginning CPR prior to full cardiac arrest results in improved survival. Place less emphasis on the pulse check. For an unresponsive and non-breathing child, begin CPR if a pulse cannot be detected within 10 seconds *NEW 2011 CPR UPDATE CHANGES: BLS Initiate CPR with chest compressions rather than rescue breaths (CAB rather than ABC). Asphyxial cardiac arrest is more common in infants and children, and ventilations are extremely important in pediatric resuscitation. The CAB sequence for infants and children is to simplify training. Therefore, start CPR with chest compressions immediately, while a second rescuer prepares to provide ventilation Compress at a rate of at least 100/min. After each compression, allow the chest to recoil completely Depth of compressions is at least one-third (1/3) the anterior-posterior diameter of the chest or approximately 1½ inches (4 cm) in infants and 2 inches (5 cm) in children. Note: Inadequate compression depth and incomplete recoil is common even among trained providers. *NEW 2011 CPR UPDATE CHANGES: BLS For the lone rescuer, a compression-ventilation ratio of 30:2 is recommended. For two rescuers, a ratio of 15:2 is recommended. Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways help maintain an open airway. Make sure to select the correct size. Deliver ventilations with as short a pause in compressions as possible. If an advanced airway is in place, compressions should be delivered without pauses for ventilation. Ventilations should be delivered at a rate of eight to 10 breaths/minute (every six to seven seconds) without interrupting compressions. Avoid excessive ventilation *NEW 2011 CPR UPDATE CHANGES: Defibrillation Follow package directions for placement of defibrillator pads. Place manual electrodes over the right side of upper chest and the apex of the heart (to left of nipple over left lower ribs). There is no advantage in an anterior-posterior position of the paddles. Paddle size: Use the largest electrodes that will fit on the childʼs chest without touching, leaving about 3 cm between electrodes. “Adult” size (8–10 cm) electrodes should be used for children >10 kg (approximately one year). “Infant” size should be used for infants <10 kg. An initial dose of 2 to 4 J/kg is acceptable. For refractory VF, itʼs reasonable to increase the dose to 4 J/kg. Higher energy levels may be considered, not to exceed 10 J/kg or the adult maximum dose If an AED with an attenuator is not available, use an AED with standard electrodes In infants <1 year, a manual defibrillator is preferred. If not available, an AED with an attenuator may be used. An AED without a dose attenuator may be used if neither a manual defibrillator nor a dose attenuator is available Broselow Tape *NEW 2011 CPR UPDATE CHANGES: PALS The PALS cardiac arrest algorithm is simplified and organized around two-minute periods of uninterrupted CPR. Exhaled CO2 detection is recommended as confirmation of tracheal tube position with a perfusing rhythm in all settings and during intra- or inter-hospital transport. Capnography/capnometry, used for confirming proper endotracheal tube position, may also be useful to assess and optimize the quality of chest compressions during CPR It may also spare the rescuer from interrupting chest compressions for a pulse check because an abrupt and sustained rise in PetCO2 is observed just prior to clinical identification of ROSC. *NEW 2011 CPR UPDATE CHANGES: PALS Upon ROSC, titrate inspired oxygen (when oximetry is available) to maintain an arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation >94% but <100% to limit the risk of hyperoxemia. Bradycardia with pulse and poor perfusion: epinephrine, atropine and pacing may be used. Tachycardia with pulse and poor perfusion: > Narrow complex (QRS <0.09) SVT: Attempt vagal stimulation. Adenosine is the drug of choice. If hemodynamically unstable or adenosine are ineffective, perform synch cardioversion, starting at a dose of 0.5 to 1 J/kg, increasing to 2 J/kg. > Wide complex (QRS>0.09) tachycardia, hemodynamically stable: Adenosine may be considered if the rhythm is regular and monomorphic and is useful to differentiate SVT from VT. Consider cardioversion using energy described for SVT. Expert consultation is strongly recommended prior to administration of amiodarone or procainamide. If hemodynamically unstable, cardioversion is recommended. SVT Stable: Vagals first, then Adenosine 0.1, 0.2mg/kg, Then cardiovert as last resort 0.5-1J/kg Unstable: Cardiovert VT with pulse: Stable: Adenosine .1, .2, Amiodarone 5mg/kg over 60 min, then cardioversion if needed. Unstable: Cardioversion VT/VF: no pulse , defib ASAP, CPR, Epi, after third shock Amiodarone *NEW 2011 CPR UPDATE CHANGES: PALS Routine calcium administration is not recommended for pediatric cardiopulmonary arrest in the absence of documented hypocalcemia, calcium channel blocker overdose, hypermagnesemia or hyperkalemia. Etomidate has been shown to facilitate endotracheal intubation in infants and children with minimal hemodynamic effect but is not recommended for routine use in pediatric patients with evidence of septic shock. Although there have been no published results of prospective randomized pediatric trials of therapeutic hypothermia, based on adult evidence, therapeutic hypothermia (to 32– 34°C) may be beneficial for adolescents who remain comatose after resuscitation from sudden, witnessed, out-of-hospital VF cardiac arrest. Therapeutic hypothermia (to 32– 34°C) may also be considered for infants and children who remain comatose after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Whenever possible, provide family members with the option of being present during resuscitation of an infant or child. CPR Practice and Competency Testing Single person resuscitation (30:2 ratio, 100 compressions a minute, 2 minute cycles) Two person resuscitation (15:2 ratio) Use of Bag/Mask (remember, always bag a patient whom becomes distressed and cyanotic on the ventilatior) CPR Practice and Competency Testing Compression techniques (one hand method, two hand, two finger or encircling thumb technique) Watch video on CPR practice, we will be practicing CPR soon Overview of PALS CPR High Quality CPR Compression rate of at least 100 per minute Push hard and fast Compression depth 1/3 AP diameter of the chest, 1 ½ inches in infants and 2 inches in pediatrics Allow proper chest recoil after each compression to allow for proper cardiac output Minimize interruptions for continuous brain and organ perfusion Avoid excessive ventilation to prevent impendence of venous return back to the heart and gastric insufflation Overview of PALS CPR AED Paddle size: Use the largest electrodes that will fit on the childʼs chest without touching, leaving about 3 cm between electrodes. “Adult” size (8–10 cm) electrodes should be used for children >10 kg (approximately one year). “Infant” size should be used for infants <10 kg. If an AED with an attenuator is not available, use an AED with standard electrodes In infants <1 year, a manual defibrillator is preferred. If not available, an AED with an attenuator may be used. An AED without a dose attenuator may be used if neither a manual defibrillator nor a dose attenuator is available Airway Management Upper airway obstruction: Note presence of stridor (typically inspiratory) Note cough (seal like, dull, muffled) Note Conciousness Note breath sounds (decreased?), note HR (typically tachycardic) Note color, retractions, grunting, tachypnea and WOB If in distress causing compromise: open airway and determine if an advanced airway is needed. Support ventilations and begin CPR as needed Possible causes: Croup, Epiglotitis, Apiration, inhaled toxins, anaphylaxis Administer nebulized epinephrine/racemic for moderate stridor/barking cough Treat underlying problem: airway, cool mist, racemic epinephrine, decadron, steroids Airway Management Lower Airway Obstruction Note presence of Wheezing (typically expiratory), prolonged expiratory phase and airtrapping Note decreased aeration in lungs, desaturation Note color (cyanosis is a late sign) Causes: Asthma, Pneumonia, Bronchiolitis, aspiration that has migrated passed trachea (unilateral wheezing) Treat with bronchodilators, bronchial hygein and bronchoscopy Advanced Airways Airway problems in the pediatric population is especially critical as it typically is the precipitating cause of pediatric arrest Advanced Airways Cuffed ETT now considered as safe or more safe than a non cuffed for small children Verify placement with exhaled CO2 detector (turns yellow for correct placement); check chest rise, breath sounds then CXR Exhaled CO2 may not be detected in prolonged arrest May use a EDD USE DOPE mnemonic when determining deterioration of an intubated patient; D: displacement of ETT, O: obstruction of the tube; P: pneumothorax; E: equipment failure Support of Ventilation The method of advanced airway support (endotracheal intubation versus laryngeal mask versus bag-mask) provided to the patient should be selected on the basis of the training and skill level of providers in a given advanced life support (ALS) system and on the arrest characteristics and circumstances (eg, transport time and perhaps the cause of the arrest). Split up into two groups Group 1. Group 2. CPR practice Intubation practice Bag and mask practice LMA overview AED practice Oxygen management 20 minutes per group then switch Airway Management Watch Airway Management Video Rapid Sequence Intubation To facilitate emergency intubation and reduce the incidence of complications, skilled, experienced providers may use sedatives, neuromuscular blocking agents, and other medications to rapidly sedate and paralyze the victim. Use RSI only if you are trained and have experience using these medications and are proficient in the evaluation and management of the pediatric airway. If you use RSI you must have a secondary plan to manage the airway in the event that you cannot achieve intubation. Airway Management CuffedVersus Uncuffed Tubes In the in-hospital setting a cuffed endotracheal tube is as safe as an uncuffed tube for infants beyond the newborn period and in children.In certain circumstances (eg, poor lung compliance, high airway resistance, or a large glottic air leak) a cuffed tube may be preferable provided that attention is paid to endotracheal tube size, position, and cuff inflation pressure Disordered control of breathing Occurs often after a head injury or as a result of aneurysm or infection in brain. Normal rhythmic breathing is altered, requires protection of airway with artificial airways. Endotracheal Tube Size Length-based resuscitation tapes are helpful and more accurate than age-based formula estimates of endotracheal tube size for children up to approximately 35 kg, even for children with short stature. In preparation for intubation with either a cuffed or an uncuffed endotracheal tube, confirm that tubes with an internal diameter (ID) 0.5 mm smaller and 0.5 mm larger than the estimated size are available. During intubation, if the endotracheal tube meets resistance, place a tube 0.5 mm smaller instead. Following intubation, if there is a large glottic air leak that interferes with oxygenation or ventilation, consider replacing the tube with one that is 0.5 mm larger, or place a cuffed tube of the same size if an uncuffed tube was used originally. Note that replacement of a functional endotracheal tube is associated with risk; the procedure should be undertaken in an appropriate setting by experienced personnel. Airway Management If an uncuffed endotracheal tube is used for emergency intubation, it is reasonable to select a 3.5-mm ID tube for infants up to one year of age and a 4.0-mm ID tube for patients between 1 and 2 years of age. After age 2, uncuffed endotracheal tube size can be estimated by the following formula: If a cuffed tube is used for emergency intubation of an infant less than 1 year of age, it is reasonable to select a 3.0 mm ID tube. For children between 1 and 2 years of age, it is reasonable to use a cuffed endotracheal tube with an internal diameter of 3.5 mm After age 2 it is reasonable to estimate tube size with the following formula Respiratory Compromise Be vigilant for signs of respiratory compromise. Often, symptoms of shock or cardiac distress are treated without regard to respiratory status, but in many cases a cardiac dysrhythmia or compensated shock can be completely resolved by aggressive oxygenation. Whenever a pediatric patient’s heart rate is too slow, or is slowing, the first and primary treatment is to give assisted ventilations if the child’s airway is not maintained or their work of breathing is not effective. For pediatric patients with any symptoms, always provide oxygen, the exact flow rate depending on patient needs. Stable patients with a cardiac dysrhythmia but no respiratory distress can receive low-flow oxygen (up to 4 L/min.) via nasal cannula. Unstable cardiac patients, patients in shock (compensated or hypovolemic), or patients with respiratory distress should receive oxygen via non-rebreather mask, if they tolerate it. Patients in respiratory failure should receive assisted ventilations via bag-mask valve. Respiratory Compromise It is critical that students correctly categorize the degree of respiratory compromise and provide appropriate oxygenation. In Respiratory Distress, the patient will have an increased respiratory rate and effort. Be alert for patient position, nasal flaring, retractions, and accessory muscle use. Skin color may be normal or pale, and the patient may exhibit the beginnings of an Altered Level of Consciousness (ALOC). Adventitious breath sounds may or may not be present. Any patient in respiratory distress should receive high-flow oxygen via nonrebreather mask, if they tolerate it. Respiratory Compromise In Respiratory Failure, the patient may have an increase in respiratory effort with increased or decreased respiratory rate. Be alert for patient position, nasal flaring, retractions, and accessory muscle use. Head bobbing, decreased respiratory effort, “seesaw” respiratory pattern, shallow respirations, cyanosis, difficulty speaking, and poor air movement (diminished or absent breath sounds) are signs of respiratory failure. For any child in respiratory failure or severe respiratory distress, you should consider the following interventions: AssistedVentilations (provide ventilations via Bag-valve Mask); Advanced Airway (consider Endotracheal Intubation); or MechanicalVentilations (such as CPAP or BiPAP). When providing assisted ventilations, students should remember that hyperventilation (ventilating too often, too rapidly, or with too much volume) will diminish the effectiveness of circulation. Exhaled or End-Tidal CO2 Monitoring When available, exhaled CO2 detection (capnography or colorimetry) is recommended as confirmation of tracheal tube position for neonates, infants, and children with a perfusing cardiac rhythm in all settings (eg, prehospital, emergency department [ED], ICU, ward, operating room) and during intrahospital or interhospital transport. Remember that a color change or the presence of a capnography waveform confirms tube position in the airway but does not rule out right mainstem bronchus intubation. During cardiac arrest, if exhaled CO2 is not detected, confirm tube position with direct laryngoscopy because the absence of CO2 may reflect very low pulmonary blood flow rather than tube misplacement. Exhaled or End-Tidal CO2 Monitoring Confirmation of endotracheal tube position by colorimetric end- tidal CO2 detector may be altered by the following: If the detector is contaminated with gastric contents or acidic drugs (eg, endotracheally administered epinephrine), a consistent color rather than a breath-to-breath color change may be seen. An intravenous (IV) bolus of epinephrine may transiently reduce pulmonary blood flow and exhaled CO2 below the limits of detection. Severe airway obstruction (eg, status asthmaticus) and pulmonary edema may impair CO2 elimination below the limits of detection. A large glottic air leak may reduce exhaled tidal volume through the tube and dilute CO2 concentration. Capnography-Show video Oxygen Ventilate with 100% oxygen during CPR because there is insufficient information on the optimal inspired oxygen concentration once the circulation is restored, monitor systemic oxygen saturation. Titrate oxygen administration to maintain the oxyhemoglobin saturation ≥94%-99% If resuscitation efforts are unsuccessful, note possible causes for the arrest: 6 H’s and 5 T’s H’s 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Hypovolemia (look for signs of fluid/blood loss. Give fluid blolus’s and reassess) Hypoxia (confirm chest rise and bilateral breath sounds with ventilation, check o2 source) Hydrogen Ion Acidosis (Resp acidosis; provide adequate ventilation but do not hyperventilate, metabolic acidosis; give sodium bicarb) Hyper/Hypokalemia (for hyper give calcium chloride 10 ml of 10% over 5 minutes, for hypo give potassium or magnesium 5ml of 50% solution) Hyper/hypothermia Hypo/hyperglycemia (check glucose with Accu-check) T’s 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Tablets (Drug OD); find antidote or reverse drug, poison control. Always ask the family for metabolic or toxic causes during resuscitation Tamponade (look for chest trauma, malignancy, central line insertion, JVD) Tension Pneumothorax- desreased BS, deviated trachea, high peak pressures or difficult to bag, chest tube with needle decompression OVER THE THIRD RIB AT THE MIDCLAVICULAR LINE Thrombosis- give thrombolytics for suspected embolus Trauma- inspect body completely, remove clothing, secure airway, control bleeding and give volume with isotonic crystalloids and blood products Arrhythmia Review Ventricular Tachycardia without Pulse and Ventricular Fibrillation PulselessV-Tach VT- series of wide bizarre QRS that produce little to no cardiac output; rate above 100 Requires immediate defibrillation with 2J/kg followed by immediate CPR If after 2 minutes still in VT or VF, shock again at 4J/kg Establish IV and give Epinephrine 0.01mg/kg Ventricular Tachycardia without Pulse and Ventricular Fibrillation V-Fib Chaotic; no defined rhythm, never a HR/pulse Requires immediate defibrillation with 2J/kg followed by immediate CPR If after 2 minutes still in VT or VF, shock again at 4J/kg Establish IV and give Epinephrine 0.01mg/kg Both of these arrhythmias will require emergent CPR, Defibrillation and Drugs! Bradycardia Bradycardia occurs when the heart beats slower than 60 beats per minute; occurs as a result of heart block or increased vagal tone. What do you do: Support ABC’s as necessary Give Oxygen Attach Monitor and prepare defibrillator Determine if bradycardia is causing cardiopulmonary compromise IF YES: Perform CPR if despite oxygenation and ventilation with bagging; the heart rate remains below 60/min with poor perfusion If bradycardia persists when rhythm is checked after 2 minutes; Give EPINEPHRINE and repeat every 3-5 minutes as necessary If patient has increased vagal tone (Physiological causes of increased vagal tone include bradycardia seen in athletes; pathologic causes include MI, toxic or environmental exposure, electrolyte disorders, infection, sleep apnea, drug effects, hypoglycemia, hypothryroidism, and increased intracranial pressure) or primary AV BLOCK; give ATROPINE first dose 0.02 mg/kg, may repeat (minimum dose is 0.1mg to maximum total dose of 1 mg) Consider pacing if drugs fail Watch for asystole and ne prepared to perform CPR If bradycardia is not causing any compromise; monitor patient, supply oxygen and aquire expert consultation. Also note possible causes H’s and T’s. Transcutaneous Pacing Not commonly performed with pediatrics, however it is utilized to supplement a failing conduction system associated with high degree blocks or severe unresponsive bradycardia Pediatric Pulseless Arrest Algorithm BLS: Initiate CPR 30:2 or 15:2 ratios; avoid hyperventilation (CAB) Bag/mask ventilate with 100% oxygen Attach monitor and prepare defibrillator Check rhythm once on monitor after 2 minute cycle of CPR. Determine if the rhythm is shockable (VT, VF) or not; also a IV/IO should be established and an advanced airway should be considered If shockable (VT, VF) Give 1 shock: manual start with 2 J/Kg; AED Resume CPR immediately after shock Give 5 cycles (approximately 2 minutes) and then check rhythm again and determine if its shockable or not If it is shockable continue CPR while defibrillator is charging and administer second shock with 4 J/Kg then resume CPR Give epinephrine at this time IV/IO 0.01 mg/kg (1:10,000 soln) or ETT; repeat every 35 minutes Keep checking rhythm after every 2 minutes to determine if it is shockable or not, if after 3 shocks VF or VT remain, consider antiarrythmics; AMIODARONE 5 mg/kg IV/IO or LIDOCAIN 1 mg/kg IV/IO’ consider Magnesium 2.5-5 mg/Kg IV/IO max dose 2g for Torsades de Pointes. If rhythm continues the same; consider H’s and T’s ASYSTOLE ASYSTOLE Algorithm: Pulseless Arrest – Not Shockable (Course Guide, page 39) Remember: DEAD: • Determine whether to initiate resuscitative efforts. • Epinephrine 0.01 mg/kg (1:10,000 solution) q 3-5 min IV/IO. Give as soon as possible after resuming CPR, circulate with chest compressions. • Aggressive oxygenation – use compression: ventilation ratio of 15:2 consider advanced airway. Avoid hyperventilation – do not ventilate too often, too quickly, or with too much volume. • Differential Diagnosis or Discontinue resuscitation – Are they still dead? Consider the 6 H’s and 5 T’s (see above) – check blood glucose; check core temperature; consider Naloxone; etc. PULSELESS ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY Algorithm: Pulseless Arrest – Not Shockable Remember: PEA: • Possible causes (consider the 6 H’s and 5 T’s). • Epinephrine 0.01 mg/kg IV/IO q 3-5 minutes. Give as soon as possible after resuming CPR, circulate with chest compressions. • Aggressive oxygenation – use compression: ventilation ratio of 15:2 consider an advanced airway. Avoid hyperventilation – do not ventilate too quickly, too often, or with too much volume. Note: In PEA, the electrical system of the heart is functioning, but there is a problem with the pump, pipes, or volume – a mechanical part of the system is not working.You can use the 6 H’s and 5 T’s to remember the most common reversible causes of PEA: Hypovolemia Toxins Hypoxia Tamponade, cardiac Hydrogen Ion (acidosis) Tension Pneumothorax Hypo-/Hyperkalemia Thrombosis (coronary or pulmonary) Hypoglycemia Trauma Hypothermia PEA will have the appearance of a sinus rhythm, however no pulse is present! Tachycardia with Pulse and Adequate Perfusion Assess and support ABC’s as needed Provide Oxygen, do not rely on SpO2 monitor, may be unreliable (mask, nasal cannula…) Attach monitor, prepare defibrillator Evaluate/Obtain a 12 lead EKG On EKG if QRS is normal (0.08 to 0.12 seconds) Probable sinus tachycardia Compatible with history consistent with known cause (fever, pain, fear…) P waves present/normal Variable R-R with consistent PR Infants: rate usually <220/min; children rate usually <180/min Treat causes (this will return rate to normal) Tachycardia with Pulse and Adequate Perfusion On EKG if QRS is narrow (less than 0.08 seconds) Probable Supraventricular tachycardia Compatible history (vague, non specific, abrupt rate changes) P waves abnsent/abnormal HR not variable with activity Infants rate >220/min, children rate > 180/min Treatment: consider vagal maneuvers first (if patient is stable), ideal vagal= ice to face in infants, establish IV and consider ADENSOSINE 0.1 mg/kg IV (maximum first dose 6 mg). Use rapid bolus technique. If patient is unstable and has no IV, cardiovert immediately. Tachycardia with Pulse and Adequate Perfusion On EKG if QRS is wide (greater than 0.12 seconds) Possible Ventricular tachycardia Consider expert consultation Search and treat possible causes Consider pharmacologic cardioversion with: Amiodarone 5 mg/kg IV over 20-60 minutes or Procainamide 15 mg/kg over 30-60 minutes (both will slow ventricular conduction and improve contractility, thus increasing cardiac output) Do not administer Amiodarone and Procainamide together May attempt Adenosine if not already administered Consider electrical cardioversion for unstable patients or if medications fail Cardiovert with 0.5 to 1 J/kg (may increase to 2 J/kg if initial dose is ineffective) Sedate prior to cardioversion Obtain 12 lead EKG Pediatric Tachycardia with Pulses with Poor Perfusion Same as previous slide; except DO NOT DELAY CARDIOVERSION FOR IV access and consider possible causes H’s and T’s Cardioversion verse Defribillation Cardioversion: 0.5 to 1 J/kg with sync mode on (may increase to 2 J/kg if 1st shock unsuccessful) use sedation with analgesia when possible For unstable SVT, VT, A-Fib, A-Flutter not controlled by Adenosine or Vagal Manuvers. Cardiovert if vascular access is not established (Do not delay cardioversion to establish IV/IO) Defibrillation: 2-4 J/kg, increase Joules, unsynchronized, for VT/VF, perform immediate CPR after shock, assess rhythm every 2 minutes; epinephrine should be given in conjunction every 3-5 minutes, 0.01 mg/kg Split up into two groups Group 1: Group 2: Review pulseless arrest Review defibrillation, algorithm and drug management, review VF/VT algorithm, Review Bradycardia and tachycardia algorithm cardioversion and T.C.P on defibrillator Medications and administration Preferred route IV/IO because ETT route is unreliable in dosing and absorption Prolonged use of Epinephrine with increasing does no longer done Watch IO insertion video Medications Adenosine 0.1 mg/kg (up to 6 mg) 0.2 mg/kg for second dose Rapid IV push, max single dose 12 mg. For SVT (after vagal manuevars) Amiodarone 5 mg/kg rapid IV/IO Max 15 mg/kg/day for refractory pulselessVT/VF Medications Atropine Sulfate 0.02 mg/kg IV/IO/TT Min dose 0.1 mg, max single dose 0.5 mg, 1 mg adolescent, may double second dose. For bradycardia after epinephrine Epinephrine 0.01 mg/kg (1:10,000) IV/IO 0.1 mg/kg (1:1000) ETT Repeat every 3-5 minutes during CPR Consider a higher dose (0.1mg/kg) for special conditions, given for VT/VF, aystole, PEA, bradycardia Medications Glucose 0.5-1 g/kg IV/IO max dose 2-4 mL/kg of 25% soln 5%= 10-20 mL/kg, 10%= 5-10 mLkg, 25%= 2-4 ml/kg in large vein Dobutamine 2-20 ug/kg/min Titrate to desired effect Dopamine 2-20 ug/kg/min Presser effects at higher doses>15 ug/kg/min Medications Lidocain 1 mg/kg IV/IO/TT (with TT dilute with NS to a volume of 3-5 ml and follow with positive pressure ventilations. Given as a alternative to Amiodarone Magnesium Sulfate 25-50 mg/kg IV/IO over 10-20 min Max dose 2 g, given for Torsades De Pointes Naloxone If <5 yr old or 20 kg: 0.1 mg/kg If >5 yr old or 20 kg, 2 mg Titrate to desired effect, for barbituate overdose Sodium Bicarb 1 mEq/kg per dose Infuse slowly and only if ventilation is adequate Management of Shock 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Give Oxygen Monitor Pulse Ox ECG monitor Blood Pressure IV/IO access BLS as indicated Bedside Glucose Management of Shock Shock results from inadequate blood flow and oxygen delivery to meet tissue metabolic demands. Shock progresses over a continuum of severity, from a compensated to a decompensated state. Attempts to compensate include tachycardia and increased systemic vascular resistance (vasoconstriction) in an effort to maintain cardiac output and blood pressure. Although decompensation can occur rapidly, it is usually preceded by a period of inadequate end-organ perfusion. Signs of compensated shock include: Tachycardia Cool extremities Prolonged capillary refill (despite warm ambient temperature) Weak peripheral pulses compared with central pulses Normal blood pressure. As compensatory mechanisms fail, signs of inadequate end-organ perfusion develop. In addition to the above, these signs include Depressed mental status Decreased urine output Metabolic acidosis Tachypnea Weak central pulses Management of Shock Signs of decompensated shock include the signs listed above plus hypotension. In the absence of blood pressure measurement, decompensated shock is indicated by the nondetectable distal pulses with weak central pulses in an infant or child with other signs and symptoms consistent with inadequate tissue oxygen delivery. The most common cause of shock is hypovolemia, one form of which is hemorrhagic shock. Distributive and cardiogenic shock are seen less often. Learn to integrate the signs of shock because no single sign confirms the diagnosis. For example: Capillary refill time alone is not a good indicator of circulatory volume, but a capillary refill time of >2 seconds is a useful indicator of moderate dehydration when combined with a decreased urine output, absent tears, dry mucous membranes, and a generally ill appearance. It is influenced by ambient temperature, lighting, site, and age. Management of Shock Tachycardia also results from other causes (eg, pain, anxiety, fever). Pulses may be bounding in anaphylactic, neurogenic, and septic shock. In compensated shock, blood pressure remains normal; it is low in decompensated shock. Hypotension is a systolic blood pressure less than the 5th percentile of normal for age, namely: ● <60 mm Hg in term neonates (0 to 28 days) ● <70 mm Hg in infants (1 month to 12 months) ● <70 mm Hg + (2 x age in years) in children 1 to 10 years ● <90 mm Hg in children >10 years of age Management of Shock Management of Shock Hypovolemic Shock Signs and Symptoms of Shock: Pale/cool/clammy skin, increased HR, BP either low (decompesated) or normal (compensated), obtunded Non-Hemmorrhagic: 20 ml/kg NS or LR bolus, repeat as needed. Consider Colloid after 3rd NS/LR bolus Hemmorrhagic: Control bleeding; 20 ml/Kg NS/LR bolus, repeat 2 or 3 times as needed and transfuse PRBCs as indicated Causes in PALS: Dehydration from illness Trauma from accidents Diarrhea, vomiting Management of Shock Septic Shock Common with sustained infection, chronic disease, immune compromised and cancer patients on chemotherapy Altered mental status and perfusion Give O2 and support ventilation as needed Establish IV/IO Obtain ABG, Lactate, Glucose, Calcium, Cultures and CBC BLS as needed Push 20 ml/kg boluses of isotonic fluid up to 3, 4 or more blouses based on patient response Correct hypoglycemia and hypocalcemia as needed Administer Antibiotics STAT Consider Vasopressor drip to maintain BP and stress dose hydrocortisonse (used to treat shock) If patient responds to fluid with normal BP send to ICU to monitor If patient does not respond: Begin vasoactive drugs; establish A-line for BP monitoring, Central line for fluid delivery; administer Dopamine for renal perfusion; administer Norepinephrine (Levophed) for blood pressure Evaluate SVO2 (goal greater than 70%, obtained from PA line) If SVO2 is less than 70% consider MILRINONE or NITROPRUSSIDE Management of Shock Neurogenic Shock (Head injury that disrupts BP regulation) Give 20 ml/Kg NS/LR bolus repeat PRN Give Vasopressor Cardiogenic Shock Follow PALS algorithms for bradycardia and tachycardia Other such as Cardiomyopathy, Myocarditis, CHD or poisoning give 510 ml/kg NS/LR bolus, repeat PRN, give Vasoactive infusion and consider expert consultation Obstructive Shock Tension Pneumothorax: Needle decompression and chest tube Ductal Dependent: Prostaglandin Ei, and cardiologist consultation Cardiac Tamponade: Pericardiocentesis and 20 ml/kg bolus NS Pulmonary Embolism: 20 ml/kg bolus, thrombolytics and anticoagulants Pediatric Assessment The AHA utilizes a specific assessment protocol known as “Assess – Categorize –Decide – Act” model: Assess the patient; Categorize the nature and severity of their illness; Decide on the appropriate actions; and Act. Once you have completed this process, begin again by reassessing the patient, always seeking additional information that will help in determining the nature of the illness or treatment of the patient. Pediatric Assessment Assess Categorize illness as a respiratory, circulatory or a combination problem Assess severity of problem Respiratory Upper vs. Lower airway obstruction Lung tissue disease Disordered control of breathing (head injury) Severity: respiratory distress, impending or failure Pediatric Assessment Circulatory (arrhythmia or shock) SHOCK: give repeated boluses of isotonic crystalloid (NS or LR) of 20 ml/kg for HYPOTENSION associated with shock Give NS or LR as initial fluids for volume replacement Isotonic Colloid given only after crytalloid is give Hypovolemic: loss of blood, dehydration, vomiting, diarrhea Obstructive: neurological impairment affecting skeletal muscles Distributive/Septic: infection migrating to major organs Cardiogenic: multiple areas of ischemic damage to the heart leading to poor output. GIVE VASOACTIVE DRUGS SUCH AS MILRINONE for compensated shock. Give medium does of Dopamine for uncompensated shock with boluses of fluid, avoid epinephrine as it increases myocardium O2 demand making ischemia worse Pediatric Assessment *Severity: Compensated (normotensive, normal systolic BP but will have a decreased level of consciouness, cool extremities, delayed capillary refill and faint distal pulses) or hypotensive (results in increased HR, low BP, and weak pulses) General Assessment Inspection (what you see: WOB, appearance, color, edema, alertness…) Primary Assessment Circulation, Airway, breathing, Disability, Exposure This is hands on assessment (vitals, Spo2, neuro status such as a patient whom responds to painful stimulus by grabbing your hand if pinched but otherwise does not respond verbally, temperature and bleeding…) Pediatric Assessment Secondary Assessment Focus on history (SAMPLE) Signs and symptoms Allergies Medications Past Hx Last Meal consumed Events leading to present problem This is a thorough head to toe examination Tertiary Assessment Lab studies, CXR, EKG, ABG…know when to obtain each. Example: know when to obtain a head CT for a MVA patient whom is unresponsive with no signs of pneumothorax Pediatric Assessment As you provide treatment, you must frequently reassess your patient (especially after initiating a therapy or intervention). Then re-categorize the patient based on the information available to you; what you first categorize (correctly) as respiratory distress may turn out to be the result of a life-threatening dysrhythmia, so you would need to recategorize the problem as cardiac once you identify the heart rhythm, and then treat the patient appropriately. Pediatric Assessment Pediatric Assessment • Cardiac: Common life-threatening dysrhythmias include SupraventricularTachycardia or Bradycardia. Patients in cardiac arrest may be in Ventricular Fibrillation, Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia, Asystole, or Pulseless Electrical Activity (PEA), which includes all other heart rhythms that present without a pulse. In pediatric patients, severely symptomatic bradycardia may require CPR. Respiratory: Respiratory problems can be broadly divided into Upper Airway Obstruction, Lower Airway Obstruction, Lung Tissue Disease, or Disordered Control of Breathing (which includes any ineffective respiratory rate, effort, or pattern. Shock: Shock (widespread inadequate tissue perfusion) can be Hypovolemic, Obstructive, Distributive (Septic), or Cardiogenic in nature. If a patient’s General Appearance indicates that they may be unconscious, you should check for responsiveness. If the patient is Unresponsive, get help (send someone to call 911 and bring back an AED, call a code, etc.). The BLS Algorithm should then be followed – open the Airway, check for Breathing, and assess Circulation. If the patient is apneic, rescue breathing started; if the patient is pulseless (or if a pediatric patient has a heart rate less than 60 with serious signs and symptoms), rescuers should begin CPR. Changes to PALS beginning later this year Chest Compressions: Push at a rate of 100 to 120 per minute Ventilation during CPR with an advanced airway: 1 breath every 6 seconds )10 per minte) while continuous chest compressions are performed Fluid Resuscitation: Initial fluid bolus of 20ml/kg is acceptable however, be cautious with children with febrile illness in settings with limited access to critical care resources (ie, vents, inotropic support) Atropine for intubation: No evidence support use for ped bradycardia delivery before intubation Changes to PALS beginning later this year Antiarrhythmic medications for shock-refractory VF or pulseless VT : Amiodarone or lidocaine is equally acceptable for the treatment of shock-refractory ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT). Targeted temperature management: For children who are comatose in the first several days after cardiac arrest (in-hospital or out-of- hospital), temperature should be monitored continuously and fever should be treated aggressively. For comatose children resuscitated from OHCA, it is reasonable for caretakers to maintain either 5 days of normothermia (36°C to 37.5°C) or 2 days of initial continuous hypothermia (32°C to 34°C) followed by 3 days of normothermia. For children remaining comatose after IHCA, there are insufficient data to recommend hypothermia over normothermia. Test Review Respiratory distress defined as an increase WOB, tachypnea with or without desaturation Respiratory failure= inadequate oxygenation/ventilation Lower airway problems= wheezing, prolonged expiratory times Upper airway problems= inspiratory stridor Disordered control of breathing = erratic breathing patterns Administer 20 ml/kg of isotonic crystalloid over 5-10 minutes initially for all shocks except cardiogenic (10 ml/kg) Intraosseous lines are ideal for shock patients, they are easy to insert and are quickly done, unlike peripheral access Obtain a bedside Glucose after fluid administration for patients in Shock Needle decompression location for pneumos Know compensated vs. hypotensive shock, know BP ranges for age groups For SVT, if unstable = cardioversion 0.5-1 J/kg. If not unstable = Vagals first, ice to face, then adenosine then shock Test Review SpO2 range for children post ROSC= 94-99% Suctioning may cause bradycardia due to vagal stimulation, be prepared to intervene if HR does not return to normal Remember DOPE for distress after intubation Give IM Epi for anaphylactic/allergic reactions First drug of choice for pulseless arrest, PEA, VF/VT, bradycardia is Epi 0.01 mg/kg Defibrillate VF/VT without pulse, first at 2 J/kg then 4 J/kg CPR = CAB, spend 10 seconds or less palpating a pulse, ratio 30:2 or 15:2, 1/3 a-p diamteter Check pulses in infants and small children in the brachial artery Use an AED on all patients if warranted. If pediatric size pads are not available for an infant you may use adult pads (anything is better than nothing) Attach AED as soon as it arrives in a code Most pediatrics have respiratory failure than leads to cardiac, if a patients breathing slows, their HR will follow, bag the patient to increase the HR Know all algorithms Testing and Megacode Mega code and Testing Groups of 5 for the mega code, you will rotate through and then return to the exam