Moral_Nature_revision_pack_LOTF

advertisement

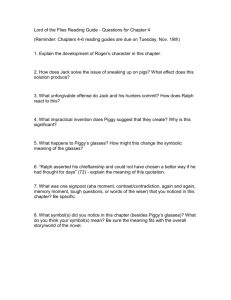

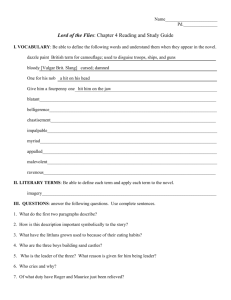

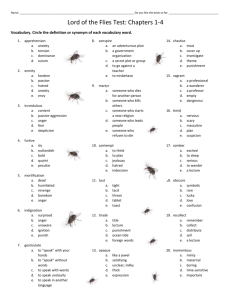

KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam "You can take spears if you want but I shan't. What's the good? I'll have to be led like a dog, anyhow. Yes, laugh. Go on, laugh. There's them on this island as would laugh at anything. And what happened? What's grownups goin' to think? Young Simon was murdered.” (Chapter 11) With the word "murdered," Piggy lays it out: there's no going back. They've killed another human being, a boy like themselves. Oh, and that boy was basically the personification of innocence and a Christ-figure, so, yeah. They're in trouble. “Then, amid the roar of bees in the afternoon sunlight, Simon found for [the littluns] the fruit they could not reach, pulled off the choicest from up in the foliage, passed them back down to the endless, outstretched hands.” (Chapter 3) Talk about innocent: Simon is the only one who bothers helping the littluns out, totally disregarding all the savage power struggles going on behind his back. "What are we? Humans? Or animals? Or savages? What's grownups going to think? Going off-hunting pigs-letting fires out-and now!" (Chapter 5) Piggy just will not let it go. The island is degenerating into anarchy, and all he can think about is what the grownups are going to think. Hint: they're probably going to be more relieved about getting their kids back than about whether a few 12-year-olds let a fire go out. "We've got to have rules and obey them. After all, we're not savages. We're English, and the English are best at everything." (Chapter 2) Weird. On the one hand, Golding does seem to believe that rules and order are necessary. On the other hand, we can't help being a little suspicious of, well, everything Jack says. Is this ironic? (We're pretty sure the "English are the best at everything" bit is, at least.) KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam “There was a space round Henry, perhaps six yards in diameter, into which [Roger] dare not throw. Here, invisible yet strong, was the taboo of the old life”. (Chapter 4) The boys still feel the pull of their previous, ordered, civilized life in England. At least for now. The world, that understandable and lawful world, was slipping away. (Chapter 5) "Lawful" sounds good, but check out how it seems to just mean "understandable." It's not that the civilized world has all the answers (it obviously doesn't), but at least there's a system of actions and consequences. A lot of driving rules might be arbitrary, but that doesn't mean you can do whatever you want. "…I mean…what makes things break up like they do? Piggy rubbed his glasses slowly and thought […]. "I dunno, Ralph. I expect it's him." "Jack?" "Jack." A taboo was evolving round that word too. Ralph nodded solemnly. "Yes," he said, "I suppose it must be." (Chapter 8) Ralph and Piggy see Jack as the reason that all their rules and order collapse. In other words, it's the dark, bestial side of us that just can't resist trying to rebel. (They don't seem to realize that there's a teeny bit of Jack in them, too.) “I just take the conch to say this. I can’t see no more and I got to get my glasses back. Awful things has been done on this island. I voted for you for KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam chief. He’s the only one who ever got anything done. So now you speak, Ralph, and tell us what. Or else –” Piggy broke off, sniveling. Ralph took back the conch as he sat down. “Just an ordinary fire. You’d think we could do that, wouldn’t you? Just a smoke signal so we can be rescued. Are we savages or what?” (Chapter 11) Ralph considers the boys savages for their inabilities – inabilities to keep order, to build a fire, to have meetings. He focuses on what they are not able to do because it is easier than looking at what they have proven themselves capable of. “You're a beast and a swine and a bloody, bloody thief!” (Chapter 11) Interesting! Ralph calls Jack both “a beast” and “a swine.” Lord of the Flies seems to argue that the boys are indeed both. The booing rose and died again as Piggy lifted the white, magic shell. “Which is better –to be a pack of painted Indians like you are, or to be sensible like Ralph is?” A great clamor rose among the savages. Piggy shouted again. “Which is better –to have rules and agree, or to hunt and kill?” Again the clamor and again – “Zup!” Ralph shouted against the noise. “Which is better, law and rescue, or hunting and breaking things up?” Now Jack was yelling too and Ralph could no longer make himself heard. Jack had backed right against the tribe and they were a solid mass of menace that bristled with spears. (Chapter 11) KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam The description of the shell as “white, magic” seems to be the way Piggy sees it. The passage that follows proves that the shell is in fact no such thing; it can’t even get the boys to quiet down and listen. The rock struck Piggy a glancing blow from chin to knee; the conch exploded into a thousand white fragments and ceased to exist. Piggy, saying nothing, with no time for even a grunt, traveled through the air sideways from the rock, turning over as he went […]. Piggy fell forty feet and landed on his back across the square red rock in the sea. His head opened and stuff came out and turned red. Piggy’s arms and legs twitched a bit, like a pig’s after it has been killed. (Chapter 11) The conch explodes, marking the end of law and order on the island. As the law ceases to exist, so does Piggy. Her bows [were] hauled up and held by two ratings. In the stern-sheets another rating held a sub-machine gun. (Chapter 12) With the arrival of the British Navy, the boys begin their return to the civilized world. Ironically, this “civilized” world is no less violent than the one the boys have been living in on the island. “You're no good on a job like this.” “All the same –” “We don’t want you,” said Jack, flatly. “Three’s enough.” (Chapter 1) While Ralph and Jack both assert authority over Piggy, Ralph at least tries to explain his reasoning (the mark of a good leader), whereas Jack brings personal insult to the matter (the mark of a bad leader). KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam "I painted my face—I stole up. Now you eat—all of you—and I—" (Chapter 4) Jack yells this right after he throws a hunk of meat at Simon. (Gross.) And, you know? We love Ralph and all, but Jack isn't exactly wrong. He did get the meat, and it's a powerful sign of leadership. If this were a real island tribe, maybe Jack should be the leader. But it's not. It's a group of little boys whose priority really should be getting off the island—and that means the right man for the job is Ralph. Jack's face swam near him. "And you shut up! Who are you, anyway? Sitting there telling people what to do. You can't hunt, you can't sing—" "I'm chief. I was chosen." "Why should choosing make any difference? Just giving orders that don't make any sense—" (Chapter 5) In case you haven't gotten it by now, Golding spells it out for us: Jack represents an autocratic government, where power is taken; and Ralph represents democratic governments, where power is given. Roger edged past the chief, only just avoiding pushing him with his shoulder. The yelling ceased, and Samneric lay looking up in quiet terror. Roger advanced upon them as one wielding a nameless authority. (Chapter 11) Elected officials can get voted out of office; autocratic rulers get forced out of office—and they're lucky if they survive. When Roger just barely avoids pushing Jack, we get the feeling that there's another power showdown on the way, and it's not going to be pretty. KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam [Jack] tried to convey the compulsion to track down and kill that was swallowing him up. "I went on. I thought, by myself—" The madness came into his eyes again. "I thought I might kill." (Chapter 3) You say pot-ay-to; we say po-tah-toe. You say this is Jack's real nature, subdued by culture; we say that the island is eroding his true self. (Or the other way around; we haven't actually made up our minds.) What does Golding seem to think? [Jack] began to dance and his laughter became a bloodthirsty snarling. (Chapter 4) Jack is taking the whole "becoming one with your prey" thing a bit too literally. Here's he's practically morphing into an animal, with the kind of "bloodthirsty snarling" you'd associate with a man-eating tiger rather than a 12-year-old choir boy. He [Jack] capered toward Bill, and the mask was a thing on its own, behind which Jack hid, liberated from shame and self-consciousness. (Chapter 4) Well, that's one way to answer the question. If Jack is hiding behind the mask, then the thing/person/creature committing these heinous acts isn't Jack; it's the mask. Is Golding giving Jack a way out? The hunters' thoughts were crowded with memories […] of the knowledge […] that they had outwitted a living thing, imposed their will upon it, taken away its life like a long satisfying drink. (Chapter 4) There's more here than a simple survivalist instinct to kill for food. The boys aren't hunting just because they're hungry; they're hunting because they need KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam the power. Hm. "Imposed their will upon it," "taken away its life"—that sounds a lot like war to us. "We spread round. I crept, on hands and knees. The spears fell out because they hadn't barbs on. The pig ran away and made an awful noise—" "It turned back and ran into the circle, bleeding—" All the boys were talking at once, relieved and excited. […] Then Maurice pretended to be the pig and ran squealing into the center, and the hunters, circling still, pretended to beat him. As they danced, they sang. "Kill the pig. Cut her throat. Bash her in." Ralph watched them, envious and resentful. (Chapter 4) We start off with boys killing pigs, then boys pretending to kill boys who are pretending to be pigs, and finally Jack hunting down Ralph in pretend—maybe— hopes of impaling his head on a stick. The boys get eased into murder, just like we get eased into reading about it. And, just maybe, that's how we get ourselves involved in bloody wars. All at once, Robert was screaming and struggling with the strength of frenzy. Jack had him by the hair and was brandishing his knife. Behind him was Roger, fighting to get close. The chant rose ritually, as at the last moment of a dance or a hunt. "Kill the pig! Cut his throat! Kill the pig! Bash him in!" Ralph too was fighting to get near, to get a handful of that brown, vulnerable flesh. The desire to squeeze and hurt was over-mastering. (Chapter 7) Blame it on mob mentality or the lure of being primitive or being called foureyes one too many times, but our sweet Ralph just went out of his skull. KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam They surrounded the covert but the sow got away with the sting of another spear in her flank. The trailing butts hindered her and the sharp, cross-cut points were a torment. She blundered into a tree, forcing a spear still deeper; and after that any of the hunters could follow her easily by the drops of vivid blood […]. Here, struck down by the heat, the sow fell and the hunters hurled themselves at her. This dreadful eruption from an unknown world made her frantic; she squealed and bucked and the air was full of sweat and noise and blood and terror […]. The spear moved forward inch by inch and the terrified squealing became a high-pitched scream. Then Jack found the throat and the hot blood spouted over his hands. The sow collapsed under them […]. At last the immediacy of the kill subsided. The boys drew back, and Jack stood up, holding out his hands. “Look.” He giggled and flecked them while the boys laughed at his reeking palms. Then Jack grabbed Maurice and rubbed the stuff over his cheeks . . . “Right up her ass!” (Chapter 8) Get all the kids out of the room, because this has just gone from understandable food-related slaughter to... something else. The hunt is no longer about just having meat to eat—it's about literally bathing in their power over a helpless animal. The dark sky was shattered by a blue-white scar. […] The chant rose a tone in agony. “Kill the beast! Cut his throat! Spill his blood!” KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam Now out of the terror rose another desire, thick, urgent, blind. “Kill the beast! Cut his throat! Spill his blood!” Again the blue-white scar jagged above them and the sulphurous explosion beat down. The littluns screamed and blundered about, fleeing from the edge of the forest, and one of them broke the ring of biguns in his terror. “Him! Him!” The circle became a horseshoe. A thing was crawling out of the forest. It came darkly, uncertainly. The shrill screaming that rose before the beast was like a pain. The beast stumbled into the horseshoe. “Kill the beast! Cut his throat! Spill his blood!” The blue-white scar was constant, the noise unendurable. Simon was crying out something about a dead man on a hill. “Kill the beast! Cut his throat! Spill his blood! Do him in!” The sticks fell and the mouth of the new circle crunched and screamed. The beast was on its knees in the centre, its arms folded over its face. It was crying out against the abominable noise something about a body on the hill. The beast struggled forward, broke the ring and fell over the steep edge of the rock to the sand by the water. At once the crowd surged after it, poured down the rock, leapt on to the beast, screamed, struck, bit, tore. There were no words, and no movements but the tearing of teeth and claws. (Chapter 9) This passage really conveys the frenzied state the boys are in when they kill Simon. But does it justify the action? Does it function as an excuse for the murder? KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam The Nature of Evil Is evil innate within the human spirit, or is it an influence from an external source? What role do the rules of society and institutions play in the existence of human evil? Does the capacity for evil vary from person to person, or does it depend on the circumstances each individual faces? These questions are at the heart of Lord of the Flies which, through detailed depictions of the boys' different responses to their situation, presents a complex view of humanity's potential for evil. It is important to note that Golding's novel rejects supernatural or religious accounts of the origin of human evil. While the boys fear the "beast" as an evil similar to the Christian concept of Satan, the novel emphasizes that this interpretation is not only mistaken but also, ironically, the motivation for the boys' increasingly cruel and violent behaviour. It is their irrational fear of the beast that informs the boys' paranoia and leads to the fatal split between Jack and Ralph and their respective followers, and this is what prevents them from recognizing and addressing their responsibility for their own impulses. Rather, as The Lord of the Flies communicates to Simon in the forest glade, the "beast" is an internal force, present in every individual, and is therefore incapable of being truly defeated. That the most ethical characters on the island-Simon and Ralph-each come to recognize his own capacity for evil indicates the novel's emphasis on the ability to be evil amongst humans. Even so, the novel is not entirely negative about the human capacity for good. While evil impulses may lurk in every human psyche, the intensity of these impulses-and the ability to control them-appears to vary from individual to individual. Through the different characters, the novel presents a variety of evil, ranging from Jack and Roger, who are eager to engage in violence and cruelty, to Ralph and Simon, who struggle to contain their brutal instincts. We may note that the characters who struggle most successfully against their evil instincts do so by appealing to ethical or social codes of behaviour. For example, Ralph and Piggy demand the return of Piggy's glasses because it is the "right thing to do." Golding suggests that while evil may be present in us all, it can be successfully suppressed by the social norms that are imposed on our behaviour from without or by the moral norms we decide are inherently "good," which we can internalize within our wills. The uncertain and deeply ironic conclusion of Lord of the Flies, however, calls into question society's role in shaping human evil. The naval officer, who becomes the boys’ saviour, is engaged in a bloody war that is responsible for the boys' aircraft crash on the island and that is mirrored by the civil war among the survivors. Are the boys corrupted by the internal pressures of an KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam essentially violent human nature, or have they been corrupted by the environment of war they were raised in? Lord of the Flies offers no clear solution to this question, provoking readers to contemplate the complex relationships among society, morality, and human nature. Civilization vs. Savagery The central concern of Lord of the Flies is the conflict between two competing impulses that exist within all human beings: the instinct to live by rules, act peacefully, follow moral commands, and value the good of the group against the instinct to gratify one’s immediate desires, act violently to obtain supremacy over others, and enforce one’s will. This conflict might be expressed in a number of ways: civilization vs. savagery, order vs. chaos, reason vs. impulse, law vs. anarchy, or the broader heading of good vs. evil. Throughout the novel, Golding associates the instinct of civilization with good and the instinct of savagery with evil. The conflict between the two instincts is the driving force of the novel, explored through the dissolution of the young English boys’ civilized, moral, disciplined behaviour as they accustom themselves to a wild, brutal, barbaric life in the jungle. Lord of the Flies is an allegorical novel, which means that Golding conveys many of his main ideas and themes through symbolic characters and objects. He represents the conflict between civilization and savagery in the conflict between the novel’s two main characters: Ralph, the protagonist, who represents order and leadership; and Jack, the antagonist, who represents savagery and the desire for power. As the novel progresses, Golding shows how different people feel the influences of the instincts of civilization and savagery to different degrees. Piggy, for instance, has no savage feelings, while Roger seems barely capable of comprehending the rules of civilization. Generally, however, Golding implies that the instinct of savagery is far more primal and fundamental to the human psyche than the instinct of civilization. Golding sees moral behaviour, in many cases, as something that civilization forces upon the individual rather than a natural expression of human individuality. When left to their own devices, Golding implies, people naturally revert to cruelty, savagery, and barbarism. This idea of innate human evil is central to Lord of the Flies, and finds expression in several important symbols, most notably the beast and the sow’s head on the KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam stake. Among all the characters, only Simon seems to possess anything like a natural, innate goodness. Ralph Ralph is the athletic, charismatic protagonist of Lord of the Flies. Elected the leader of the boys at the beginning of the novel, represents order, civilization, and productive leadership in the novel. While most of the other boys initially are concerned with playing, having fun, and avoiding work, Ralph sets about building huts and thinking of ways to maximize their chances of being rescued. For this reason, Ralph’s power and influence over the other boys are secure at the beginning of the novel. However, as the group gradually succumbs to savage instincts over the course of the novel, Ralph’s position declines quickly while Jack’s rises. Eventually, most of the boys except Piggy leave Ralph’s group for Jack’s, and Ralph is left alone to be hunted by Jack’s tribe. Ralph’s commitment to civilization and morality is strong, and his main wish is to be rescued and returned to the society of adults. In a sense, this strength gives Ralph a moral victory at the end of the novel, when he casts the Lord of the Flies to the ground and takes up the stake it is impaled on to defend himself against Jack’s hunters. In the earlier parts of the novel, Ralph is unable to understand why the other boys would give in to base instincts of bloodlust and barbarism. The sight of the hunters chanting and dancing is baffling and distasteful to him. As the novel progresses, however, Ralph, like Simon, comes to understand that savagery exists within all the boys. Ralph remains determined not to let this savagery overwhelm him, and only briefly does he consider joining Jack’s tribe in order to save himself. When Ralph hunts a boar for the first time, however, he experiences the exhilaration and thrill of bloodlust and violence. When he attends Jack’s feast, he is swept away by the frenzy, dances on the edge of the group, and participates in the killing of Simon. This first-hand knowledge of the evil that exists within him, as within all human beings, is tragic for Ralph, and it plunges him into listless despair for a time. But this knowledge also enables him to cast down the Lord of the Flies at the end of the novel. Ralph’s story ends semi-tragically: although he is rescued and returned to civilization, when he sees the naval officer, he weeps with the burden of his new knowledge about the human capacity for evil. KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam Jack The strong-willed, egomaniacal Jack is the novel’s primary representative of the instinct of savagery, violence, and the desire for power—in short, the antithesis of Ralph. From the beginning of the novel, Jack desires power above all other things. He is furious when he loses the election to Ralph and continually pushes the boundaries of his subordinate role in the group. Early on, Jack retains the sense of moral propriety and behaviour that society instilled in him—in fact, in school, he was the leader of the choirboys. The first time he encounters a pig, he is unable to kill it. But Jack soon becomes obsessed with hunting and devotes himself to the task, painting his face like a barbarian and giving himself over to bloodlust. The more savage Jack becomes, the more he is able to control the rest of the group. Indeed, apart from Ralph, Simon, and Piggy, the group largely follows Jack in casting off moral restraint and embracing violence and savagery. Jack’s love of authority and violence are intimately connected, as both enable him to feel powerful and exalted. By the end of the novel, Jack has learned to use the boys’ fear of the beast to control their behaviour—a reminder of how religion and superstition can be manipulated as instruments of power. Piggy Ralph’s “lieutenant.” A whiny, intellectual boy, Piggy’s inventiveness frequently leads to innovation, such as the makeshift sundial that the boys use to tell time. Piggy represents the scientific, rational side of civilization. William Golding firmly believed that there is no room for the thinkers in the world. No room for common sense and cleverness. Through the character of Piggy, Golding accurately conveys his feelings and shows us yet another, purer aspect of human nature. Piggy is the oddball. The freak, so to speak, in a circus of handsome, able bodied boys who laugh and humiliate him without thought for his feelings. “My auntie told me not to run….on account of my asthma” With this quote, we are introduced to Piggy, the fat bespectacled boy with asthma who is never taken seriously. However, it is Piggy who discovers the conch, the symbol of authority, civilization and peace, and it is him who presents Ralph with the idea of a meeting. Obviously made fun of in school, Piggy is treated like an outcast and is often left out, but the group do not hesitate to use his ideas if they work to KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam their advantage. Piggy is treated like the nanny, and is constantly being made to look after the ‘littleuns’. Even though he is ridiculed, Piggy’s glasses are still crucial to the boys’ survival, for keeping the signal fire lit, and for lighting the fire to roast Jack’s kill, which shows that without knowing it, the boys depend on Piggy a lot more than they think. It is Piggy who realises and recognizes their eventual turn to savagery, and although he protests: “What are we? Humans? Or animals? Or Savages?”, he is not paid any heed. As Jack and Ralph drift apart, it is only Piggy’s loyalty that keeps him with Ralph, and they grow closer, with Ralph slowly realising Piggy’s natural intelligence and insight, and relying on it more and more. Without Piggy, there would be no democracy and no conch, and it makes us wonder whether he should not have been elected the leader in the first place. Blinded when is glasses are stolen, Piggy is killed brutally when Roger drops a rock on him from above. Ralph realises this awful loss, and at the end of the novel, he “wept for the end of innocence, the darkness of man’s heart, and the fall through the air of a true wise friend called Piggy”, a quote that summarises the whole point and meaning of the novel. Piggy represents a part of human nature that the author believes has no part in any society. A part of human nature that will surely be crushed and destroyed at the first sign. A part of human nature that if we did not have it, would leave the world in a state of chaos and confusion. Simon Whereas Ralph and Jack stand at opposite ends of the spectrum between civilization and savagery, Simon stands on an entirely different plane from all the other boys. Simon embodies a kind of innate, spiritual human goodness that is deeply connected with nature and, in its own way, as primal as Jack’s evil. The other boys abandon moral behaviour as soon as civilization is no longer there to impose it upon them. They are not innately moral; rather, the adult world—the threat of punishment for misdeeds—has conditioned them to act morally. To an extent, even the seemingly civilized Ralph and Piggy are products of social conditioning, as we see when they participate in the hunt-dance. In Golding’s view, the human impulse toward civilization is not as deeply rooted as the human impulse toward savagery. Unlike all the other boys on the island, Simon acts morally not out of guilt or shame but because he believes in the inherent value KS4 – AQA Certificate in Literature – LOTF – Human Moral Nature Miss Gillam of morality. He behaves kindly toward the younger children, and he is the first to realize the problem posed by the beast and the Lord of the Flies—that is, that the monster on the island is not a real, physical beast but rather a savagery that lurks within each human being. The sow’s head on the stake symbolizes this idea, as we see in Simon’s vision of the head speaking to him. Ultimately, this idea of the inherent evil within each human being stands as the moral conclusion and central problem of the novel. Against this idea of evil, Simon represents a contrary idea of essential human goodness. However, his brutal murder at the hands of the other boys indicates the scarcity of that good amid an overwhelming abundance of evil. Essay structure idea Introduction – Introduce the novel and its context, discuss Golding’s theory about ‘mankind’s essential illness’. Main body – Track the boy’s loss of innocence. It is a good idea to start by discussing the boy’s actions when arriving on the island and then look at their descent in to savagery and how this causes them to lose their innocence. Don’t forget to analyse your quotes in detail and use word analysis to support your discussion. Use PEDAL and make sure you are answering the essay question (link back). Conclusion – Draw all your findings together to discuss your final answer/opinion. “mankind’s essential illness” Mankind and society must have rules. If we are left to our instincts we will destroy each other and ourselves. Two philosophers were big supporters of this: THOMAS HOBBES believed that if people were left alone they would constantly fight among themselves and to escape this chaos they would enter into a social contract in which they would appoint a ruler who ensured peace and order. JOHN LOCKE also supported this.