Student/Faculty Research Day

advertisement

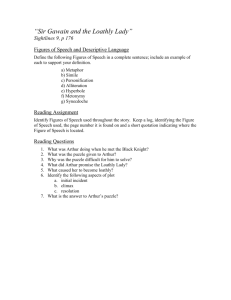

The Legend of King Arthur in History Erin Pevan In collaboration with Dr. Matthew Waters Department of History University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire The Legend of King Arthur The fanciful tales of the adventures of King Arthur provide many with a romanticized vision of the Middle Ages. In popular legend, King Arthur embodies the ideal of medieval chivalry and the quest for justice. The most popular of the stories included his acquisition of power from his father Uther Pendragon (the Sword in the Stone), Arthur’s marriage to Guinevere, the quest for the Holy Grail, the adventures of Sir Tristram (or Tristan), the life and madness of Sir Launcelot (or Lancelot), the adulterous affair between Guinevere and Launcelot, the birth and strife of Mordred, and the death of Arthur and his journey to Avalon. The life of the real historical Arthur, if such existed, resembled very little of the life of the legendary hero. The real Arthur most likely came from a time in the later fifth century, when Britain suffered invasions from Saxons, Scots, and Picts after the departure of the Roman forces in 410 C.E. In this world, no Round Table or romantic intrigues existed; Arthur’s world saw much hardship, blood, tyranny, and death. The real Arthur existed as a figure far removed from the chivalrous king of Malory’s story, and he led a life protecting the people of Britain from invasion. The Sources: Literary and Historical Literary: Fictional tales containing information on King Arthur Le Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory (c. 1450 - 1470) The Mabinogion Author unknown (11th century) Historia Regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain) by Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1136 - 1138) Historical: Medieval documents containing information of historical figures and events that resemble the stories of King Arthur Easter Annals: confirmed author unknown, but often attributed to Victorius of Aquitaine (late 5th century) De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (Concerning the Ruin and Complaint of Britain) by Gildas (c. 530540) Letter to Riothamus, King of the Britons [Brittones] by Sidonius Apollinaris (c. 470) Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People) by Bede (c. 731) Historia Britonum (History of the Britons) by Nennius (c. 800) Annales Cambriae (Welsh Annals) Author unknown (c. 950 - 970) King Arthur, Charles Ernest Butler The Court of King Arthur, artist unknown The Three Candidates for the Historical Arthur Riothamus Riothamus lived in the early fifth century as a warlord, and possibly a king, fighting throughout Britain, Ireland, and the area of modern-day France. His ethnicity remains unknown, but scholars believe Riothamus lived as a king of Britain, Ireland, Brittany, or of a British colony called Armorica (modern day France). While although relatively little has been discovered about the life of this man, many important parallels between Riothamus and Arthur have been assessed that suggest Riothamus could have been the legendary King Arthur. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, Arthur traveled to the region of Gaul twice, in order to assist a Roman emperor with a civil war caused by the emperor’s own generals. Scholars theorize Riothamus went to Gaul in 468, in order to subdue a civil war on behalf of the Roman Emperor Leo I. They also assert that Riothamus continued his Gallic campaigns into an area, though not specifically named, that closely resembled the setting for the adventures of Sir Launcelot in Malory’s work. Sidonius Apollinaris spoke of the decline of the Gaulish territories, and appealed to Riothamus to end the terrible acts of the Bretons. This short letter speaks volumes in that it places Riothamus, the “King of the Brittones”, in Gaul in 470. The Gallic campaigns of Arthur, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth, occurred within the same time period. Arthur’s betrayer bore the name “Morvandus”, rather than the traditional Mordred, while Arvandus became the nemesis of Riothamus when Riothamus traveled to Gaul in the late fifth century to help Rome put down the rebellion of its Gaulish subjects and their allies, the Visigoths. Lastly, Arthur journeyed to Avalon whilst mortally wounded from his last battle. Riothamus, fatally wounded from the Battle of Burgundy in 470, was last recorded as escaping to friendly territory near a town called Avallon. The comparisons between Riothamus and Arthur provide the most evidence from which one could conclude that Riothamus served as the model for the legendary King Arthur. While they do not specifically produce this conclusion in and of themselves, the similarities do provide the proper context in which to connect Riothamus to the Arthur of literary tradition. Ambrosius Aurelianus Ambrosius Aurelianus remains a favorite of scholars as the historical King Arthur. The historical sources researched spoke of Ambrosius directly, and stated his name in situations specifically associated with the historical King Arthur. The works of Gildas and Bede mentioned an Ambrosius Aurelianus, seemingly of Roman descent, who was the leader of the Britons following the retreat of the Saxon forces between the years of 490 and 516. Geoffrey of Monmouth also connected Ambrosius directly to Arthur, although Ambrosius became the uncle of Arthur rather than Arthur himself. Little else is known about Ambrosius other than his name, his possible Roman heritage, and that he may have led campaigns against the Saxons, much like Arthur did in the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth. Despite the frequency of his name and the ambiguous connections between the person and his actions, little other evidence exists which can concretely connect Ambrosius Aurelianus to King Arthur. Arthur in the Movies Excalibur (1981): film adaptation of Le Morte d’Arthur First Knight (1995): modern version of the classic love story Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975): hilarious version of the adventures of King Arthur & his Knights King Arthur (2004) : film that deviates from the literary tradition and focuses upon the story of the historical King Arthur, combining the stories of several Arthurian historical candidates The Lady of Shalott, 1888 by John William Waterhouse Lucius Artorius Castus Difficulty develops in trying to establish Lucius Artorius Castus as the historical King Arthur. The reasons for this difficulty have derived from a variety of sources, including the name, time period, and ethnicity of Lucius Artorius Castus. The historical Lucius Artorius Castus lived in the second century, long before the accepted period of the historical King Arthur in the late fifth – sixth centuries. Few events occurred in the second century that could be parallels for the events in the literary tradition. Lucius was almost certainly Roman, and much evidence from the early sources suggested that Arthur was probably Welsh, or in the least, a Briton. Lucius may have been halfRoman, the product of a Roman-Briton union, but the evidence for this is scarce. Some scholars assert that Artorius is a Latinized version of the Welsh name Arthyr, given to Lucius to indicate his British heritage while keeping the name itself Roman. Despite these problems, small parallels provide some evidence for the case of Lucius as Arthur. The Lucius Artorius Castus of the second century may not have been Arthur, but a descendant of the same name could have been. Both Lucius and Arthur were given the title dux bellorum, the latter given this name in Nennius. Also, just as Arthur defended his people from the invasions of the Saxons and from the rebellion of dissidents such as Mordred, so too did Lucius defend the British territories from invasions of the Picts and Scots, and maintained peace for the British subjects of Rome. While the evidence presented provides ample reasons to connect Lucius Artorius Castus with King Arthur, most of this evidence remains highly circumstantial at best. Little historical evidence of the life of Lucius Artorius Castus exists, and therefore we have little upon which to connect him to King Arthur. Works Consulted & For Further Information •Le Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory •Arthur King of Britain: History, Chronicle, Romance, & Criticism by Richard L. Brengle Acknowledgements and Special Thanks to: •The Discovery of King Arthur & The Quest for Arthur’s Britain by Dr. Matthew Waters – Department of History & Department of Foreign Languages Geoffrey Ashe Dr. Thomas Miller – Department of History •Pendragon: The Definitive Account of the Origins of Arthur by Steve Office of Research and Sponsored Programs Faculty/Student Research Collaboration Blake & Scott Lloyd •King Arthur by Norma Lorre Goodrich Funding Provided By: Differential Tuition Office of Research and Sponsored Programs Faculty/Student Research Collaboration