part 2 - La Salle University

advertisement

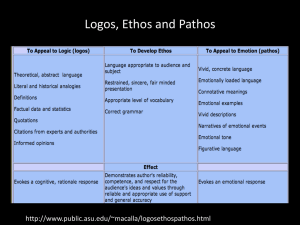

Rhetorical Theory Notes from Keith & Lundberg part II (chapters 4, 6) Argument and persuasion • Rhetoric = positive techniques, not “tricks” • Outside of force or threats, you need persuasive arguments to get people to think , feel or do something (cognitive-affectivebehavioral effects) • Speaker = audience—they will make their own decisions, using their standards; speaker is no better than audience Proofs (ways to persuade) • Aristotle coined logos (speech-based), ethos (sender-based), pathos (receiver-based) • Logos: same root as • “logical” ; this initially meant that the speech persuaded through a series of logical steps [it can also mean that the speech has logic because it is supported by good evidence, which means truthful facts, data] • Steps can be a syllogism: 2 premises lead to a conclusion • Aristotle is a man • All men are mortal • Therefore Aristotle is mortal • Or an enthymeme, which leaves out the second step because it assumes the audience knows it: • Aristotle is a man therefore he is mortal We use this reasoning when we say Where there’s smoke there’s fire (smoke is a sign of fire); Drugs cause poor grades [what are counter-arguments to that—what’s missing or assumed?]; Fixing a car is like cooking—you need the right ingredients and the right recipe (analogy; again how could you argue with this?) • Or just use some examples to build up an argument (this is induction, going from specific to general; deduction is going from general to specific) • I see a dog and it has 4 legs, more dogs also have 4 legs. So I conclude (through induction, and enough dogs) that dogs have 4 legs. • I understand from other knowledge e.g. of biology that mammals such as dogs have 4 legs. I state as a general principle that dogs must have 4 legs [we call it a theory; scientists call it a hypothesis]. I then conclude (through deduction) that if I see a specific dog, it will be 4-legged. • In rhetoric, examples can be real or hypothetical (“what if you were wrongly convicted of murder”?); this often appeals to emotions of audience Ethos • Ethos has a root similar to • “ethics” or “ethical” but means the reputation of the speaker; If I say it you might be persuaded, but if the president says it you’re more likely to be persuaded • The relationship is that people of high reputation generally are ethical (honest, believable, trustworthy) people • Speakers can create strong ethos by • Their actions (“Practice what you preach”) • Explaining how their beliefs fit the audience (“We are alike so believe as I do”) • Showing their expertise, or credentials (assuming those are real and meaningful rather than saying “Take my word on this”) Pathos • What are the linguistic or etymological connections with words we know? • Pathetic, for one—something that evokes emotion (sadness) • Pathos is created in the audience by appeals to emotion in the speech, attempts to get the audience’s emotions in line with the speaker’s conclusions • Choice of examples—metaphors, images, words—can help create pathos that works; are they “demonstrators,” “protestors,” “radicals,” “anarchists”? Is that animal a victim or an experimental subject? • Pathos alone (e.g. gory pictures) rarely works Topoi • These (plural of topos), connected to • Topography = place as in topographical maps • Are general forms that arguments take; Greeks saw these as existing in space; you got to know the landscape • Note the examples are all If A, then B • If more likely thing does not happen, less likely will not • If person has a motive, they will act on it • If you support a standard, it applies to you (don’t be a hypocrite) • If things are alike in general they will be alike in specifics (analogy—fixing a car is like cooking a meal) Issues • An issue is anything people can take sides on (take issue with) • Two arguments that aren’t easily resolved clash or have stasis; (are static—don’t move) this is something you are looking for in your research paper • To argue, the two sides must be on the same point, not talking past each other: • Can a government restrict gun ownership? • Does gun ownership increase death, violence? • If the issue is legal or policy, there are certain set points of stasis (e.g. what are the facts) • These are: presume that the innocent, or the status quo wins in a tie, so the other side has the burden of proof its case to win [“Tie goes to the runner”]; this prevents rash decisions or policies Fallacies • Fallacy = an error in logic or reasoning; can damage your ethos • Non sequitur = • Not in sequence, doesn’t follow; “It’s a nice day so vote for me” • Ad hominen (Homo sapiens= person) attack the person and say their ideas are wrong: “The Occupy people are a bunch of crazy radicals so don’t listen to them” • Ad populum (populace=people, popular) everyone believes it so it must be true • Appeal to authority: someone has a Ph.D. (high ethos) but it’s in a different subject than they are discussing (e.g. Dr. Laura) • Appeal to ignorance: there’s no proof against it so it must be true (UFOs, aliens) Fallacies (cont.) • Guilt by association, or stereotyping: Democrats believe this so we Republicans should be against it • Post hoc ergo propter hoc = faulty cause and effect; If A then B, B was caused by A—again why might this be wrong? (also faulty is to say correlation = causation where A goes up/down and B also goes up/down) • Because we have no proof of the connection—how was it caused; and because some other factor C might have caused B, or have caused both A and B to go up; or with correlation B might have caused A • Classic example: Length of women’s dresses correlates with price of coffee in Brazil; can we see any cause and effect here? Fallacies (cont.) • Red herring—take the argument off-topic • Slippery slope: we know that A can lead to B and B to C and C to D, so if A happens, D will follow; what’s wrong? • One of these might break the chain: most gum chewers later drink alcohol, alcohol drinkers are more likely to take drugs, therefore chewing gum leads to drugs • [Section on Kenneth Burke is interesting, important to know who he was; main ideas]: • Humans react to the use of symbols; humans naturally add value judgments to hierarchies (we change the nominal e.g. black and white to the ordinal e.g. black is less than white in some sense; we think good things can’t be overdone; we are persuaded by people we identify with (who we feel are like us) Style (chapter 6) • Figures of speech make your rhetoric more persuasive • Antitheses-contrast the first statement with the second: One small step for a [note] man, one giant leap for mankind [also sort of a parallelism] • Repetition of • Sounds • Alliteration (she sells sea shells …) • internal rhyme (If the glove don’t fit …) • Words or phrases: often at the same point of a sentence: We will fight in the fields, we will fight in the trenches • Klimax: a layering of ideas: not today, not tomorrow, not in my lifetime, your lifetime • Also look for ones in classic quotations: I came, I saw, I conquered; Give a man a fish … (often Shakespeare or Bible) Tropes • Use substitute words or phrases: more colorful, complex, elegant, artistic way of expressing something: surf the Net [and, a Web page is not really a page] • Metonymy: old word still holds meaning: the press still means the news media to us; we the people • Synecdoche: represent something by a part: “On Broadway production” means major theater in NYC, but they’re not all on Broadway; also the White House is just one person there • Metaphor: The defense was a brick wall (All the world’s a stage); recall simile, actually a type of analogy, uses “like” or “as”: He was as big as a house • Burke and others see these tropes as key to why rhetoric works (they are playful, clever, inventive, seductive?) • Identity tropes: (We the people) also are key