Transaction analysis - the Babson College Faculty Web Server

advertisement

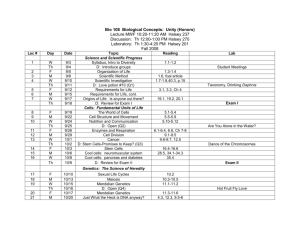

Agenda We will review the Balance Sheet – The concept of Liquidity – Valuation bases for assets and liabilities (Historical Costing) – Asset write-downs We will also review the Income Statement – Revenue and expense recognition (accrual accounting) – Non-recurring (transitory) items © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey There are two concepts that guide the placement of assets and liabilities on the balance sheet and the amounts at which they are reported. These are liquidity and historical costing. We will address each in turn. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Liquidity refers to cash. An asset is said to be “liquid” if it can be sold and converted to cash quickly. Assets are listed on the balance sheet in order of their liquidity, or how quickly they are expected to be converted to cash. For example, cash is listed first, followed by investments in marketable securities, accounts receivable, inventories, then property, plant and equipment and other long-term assets. Likewise, liabilities are listed in order of their maturity, that is, how soon they will require the payment of cash. Short-term debts are listed first, followed by long-term liabilities, then stockholder’s equity. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Balance sheets are divided into two categories which relate to liquidity and maturity: current and long-term. Current assets are assets that are expected to be converted to cash within one year of the balance sheet date. Current liabilities are liabilities that are expected to be paid usually within one year of the balance sheet date. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Examples of current assets are cash, investments in marketable securities, accounts receivable, inventories and prepaid expenses. Examples of current liabilities are accounts payable, taxes payable, accrued liabilities and the current portion of long-term debt. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey An important concept in the evaluation of the financial condition of a company is the relation between the dollar amount of current assets and current liabilities. A large amount or current assets relative to current liabilities indicates that the company can probably withstand a decline in business activities and still meet its contractual obligations. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Net working capital is defined as: NWC = $current assets - $current liabilities. We generally want this amount to be positive and larger rather than smaller. Since net working capital will generally be larger for bigger companies than for smaller companies, it is not very useful for comparisons between companies or even for the same company over time if it has changed significantly. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey As a result, analysts often convert net working capital to a ratio, called the current ratio, that is defined as follows: Current ratio = Current Assets Current liabilities We generally want this ratio to be greater than 1.0 and larger rather than smaller. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The second concept governs the amount at which assets and liabilities are reported on the balance sheet. It is called Historical Costing. Assets and liabilities are all initially recorded at their cost, either their purchase price as in the case of assets or, for liabilities, at their face amount (an exception is long-term liabilities which we will cover in a later chapter). © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Once assets and liabilities have been recorded on the balance sheet, they generally remain at their initial cost and their carrying amount is not adjusted for subsequent changes in their market values. This means that if a company purchases inventory for resale, it is reported on the balance sheet at its initial cost, not at its retail selling price. Also, if a parcel of land increases in value, that increase is not reported on the balance sheet, nor is it reflected as income, until the land is sold. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey But, if the purpose of financial reporting is to provide information that is useful to price a company’s securities, wouldn’t current market values be more relevant? Yes - but allowing companies to report market values on their balance sheets would introduce greater subjectivity into the reporting process and render them more susceptible to bias. This bias can arise either from the inability of company managers to measure accurately the market value of their assets, or it might arise if managers intentionally manage the reported values in order to mislead users of their financial statements. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey There is an inherent tradeoff in financial reporting between relevance and reliability. The use of historical costing is generally viewed as preferable by the accounting profession since it is more objective and verifiable (subject to audit). You need to understand, however, that balance sheets do not reflect market values and the price of a company’s stock will usually be different from the net book value of its stockholder’s equity. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey There are exceptions to the general principle of historical costing which we will look at more closely as the course progresses: Accounts Receivable are reported at net realizable value (face value less expected uncollectible accounts) Marketable short-term investments are reported at market value Inventories and long-term assets are written down to market value if there has been a permanent decline. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The Income Statement There are two possible ways to measure income and expense. The first is to record income when cash is received and expense when cash is paid. This is called cash basis accounting. Unfortunately, this method is not acceptable under GAAP. Public companies are not permitted to prepare their financial statements using cash basis accounting. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The second method, which is the only method acceptable under GAAP, is called accrual accounting. Accrual accounting focuses on increases and decreases in all assets and liabilities to determine income and expense instead of just focusing on cash. There are two principles which comprise the foundation for accrual accounting. They are the revenue recognition principle and the matching principle. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Under the revenue recognition principle, revenues are reported when two conditions are met: The revenue has been realized or is realizable. That means that either cash has been received or is in the form of an account receivable. Notice, therefore, that revenue can be reported even though no cash is received. The revenue has been earned. This means that the company has performed everything that it is required to do as part of the sale. Revenue cannot be reported, for example, if the customer has a right of return privilege or if the company has future obligations relating to the sael. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The matching principle requires all expenses that have been incurred to generate revenues during the period to be recognized in the same period in which we recognize the revenue. The order is this - we first decide what revenues to recognize using the revenue recognition principle (when it is earned and realized or realizable). Next, we recognize all expenses that have been incurred in order to generate that revenue. Expenses are , therefore, matched against the revenues they help to generate in the period that the revenues are recognized © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey An example of the matching principle is depreciation. When a long-term asset is purchased, its cost is recorded on the balance sheet as an asset (since it will provide future benefits). We, then, recognize as expense a portion of the asset’s cost each period to match against the revenue produced by the asset over its useful life (the cost is transferred from the balance sheet into the income statement as depreciation expense). The objective is to spread the cost out over the period of time during which the asset is expected to produce revenues. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Let’s look at some examples relating to revenue and expense recognition. Annual reports contain a description of the company’s revenue recognition policies. Here is an example from Colgate-Palmolive’s annual report: Revenues are reported at the time of product shipment. At that point, Colgate-Palmolive has fulfilled its obligation to its customer and the revenue has been earned. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Sometimes, however, cash is received prior to delivery of the product (or performance of a service). Since the revenue has not yet been earned, we must record a liability called deferred revenues to reflect our obligation to deliver the product in the future This is accomplished with the following journal entry: Cash xxx Unearned income xxx Cash is increased to reflect the inflow and a liability (unearned income) is reflected on the balance sheet to reflect the obligation to provide the product in the future. No revenue or profit is recorded until it is earned. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey When the product is delivered in the future, the liability is reduced and earned income is reported in the income statement equal to the proportion of the product that has been delivered. A simple example of this is in the magazine publishing industry. When subscriptions are received, firms make an entry like the one we just discussed since no revenue has been earned. As magazines are shipped, a portion of the liability is reduced with each shipment and revenues are reported in the income statement. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey This can be seen the the following note from the annual report of Time-Warner, the publisher of Time magazine: Revenues and Costs Publishing and Music The unearned portion of paid magazine subscriptions is deferred until magazines are delivered to subscribers. Upon each delivery, a proportionate share of the gross subscription price is included in revenues. Reported revenues, therefore, are a proportion of the subscriptions received, where the proportion is equal to the number of magazines delivered compared to the number purchased with the subscription. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Revenue recognition issues also arise when firms utilize contracts that extend over multiple reporting periods. They must, then, estimate the proportion of the total revenue that should be recognized in each period. This is typically accomplished through the use of the percentage-of-completion method. Basically, revenue is recognized in proportion to the amount of costs incurred to date in performance of the contract compared with the total costs that are expected to be incurred in order to meet the requirements of the contract. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey For example, assume a company has a contract for $10 million to build a bridge and expects that the project will cost $8 million. If it incurs costs of $2 million during the year on the project, it will report revenues of $2.5 million ($10 million * $2 million / $8 million). © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Here is an example of the percentage-of-completion method utilized by Johnson Controls to recognize revenue on its long-term contracts: © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Let’s also take a look at some issues relating to expense recognition. Under normal circumstances, the cost of fixed assets is reported on the balance sheet less an allowance for depreciation. Their cost is, thus, recognized gradually in the income statement as the asset is used up. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Sometimes, however, the asset becomes “impaired.” This means that its expected cash flows are significantly less than originally expected such that it is not likely that the original cost of the asset can be recovered. In this case, the carrying amount of the asset must be written down and that write-down reflected as an additional one-time expense in the income statement. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Take a look, for example, at the notes from the annual report of Bethlehem Steel: © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The write-down to which the company refers is further described in note “B”: This write-down related to the closure of a mill whose expected earnings and cash flows had declined significantly. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey As a second example of expense recognition, sometimes expenses are recognized in advance of their payment. This is called an “accrual.” For example, we accrue for employee compensation earned during the period to match against reported revenues even though the payment might not be made until the next payroll period. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey An expense that has become increasingly more common relates to restructuring activities. When companies restructure their operations, that activity might involve the closure of facilities and the severance of employees. As facilities are closed, their loss in value is usually reflected in an asset write-down similar to the writedown taken by Bethlehem Steel. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The expenses related to severance of employees is usually reflected as an accrual in which an expense is recorded for the anticipated costs of the severance and a liability is recorded for the anticipated payment. Let’s take a look at the notes to the DuPont annual report which detail the costs involved in its worldwide restructuring program: © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey This is the note relating to DuPont’s restructuring program which cost the company $577 million. Most of the charge ($310 million) related to anticipated severance of employees © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The remaining portion ($267 million) related to asset write-downs © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Transitory Items Up to this point, we have considered income statements of the following form: Sales - Operating expenses = Profit Some operating expenses, however, are one-time occurrences. The FASB felt that inclusion of these expenses with other operating expenses might mislead users of financial statements © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Remember, one of the purposes of financial reporting is to provide information that is useful to investors and creditors in predicting the amount, timing and uncertainty of future cash flows. If these “transitory items” were included with other operating expenses, estimation of future operating expenses, and thus net profit, would be more difficult. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey As a result, the FASB reformatted the income statement to require certain transitory (non-recurring) items to be reported separately. The following is the format we employ today: + = = Sales Cost of Goods Sold Gross Profit Operating Expenses Income from Continuing Operations Discontinued Operations Extraordinary Items Changes in Accounting Principles Net Profit © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Discontinued items relate to segments of a company that it intends to sell. Once a company has decided to divest itself of these operations, their sales and operating expenses are taken out of the income statement and the net profit or loss for these discontinued operations is reported separately on the income statement below income from continuing operations. Only the net profit (loss) is reported together with the gain or loss on the sale of the business segment. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Here is the income statement of Venator Group, Inc which owns retail athletic stores like Foot Locker. The Company reported a loss of $139 million relating to discontinued operations, $26 million in operating losses and a $113 million loss on their sale. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Additional details about these operations are found in the notes to the annual report. The discontinued operations related to the International General Merchandise which lost $9 million during the year and the Specialty Footwear segment which lost $17 million. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Companies are also required to separate expenses called extraordinary items. These are defined as extraordinary if they are both “unusual” and “infrequent”. In practice, extraordinary items usually relate to gains or losses on the retirement of long-term debt (we will cover this topic in detail in a later chapter). Let’s take a look at an example of an extraordinary item form the annual report of Du Pont: © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Notice the extraordinary loss of $201 million relating to Early Extinguishment of Debt © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey This loss is more fully described in the notes to the company’s annual report: During the year, the company repaid long-term debt before its scheduled maturity. The amount paid to repay the indebtedness was greater than the amount reported on its balance sheet, hence the loss. We will cover the accounting for debt repayment in the chapter on long-term liabilities. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The third “transitory item” reported below income from continuing operations are Changes in Accounting Principle. Here is an example of the disclosure relating to a $21 million after-tax charge reported by Boston Scientific: © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey And here is the way it appeared in the company’s income statement © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey A couple of closing remarks about transitory items: You should scrutinize these vary carefully to understand their cause. The object is to discern whether they convey information about the remaining core operations that will help you to forecast their future cash flows. You should understand that not all transitory items are separated and reported below income from continuing operations. Gains and losses on sales of assets are a common example. If the assets are not a part of discontinued operation, they are reported in income form continuing operations. You, then, need to closely examine the notes to the financial statements for information relating to the sale. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Here is the income statement of the Wrigley company, the chewing gum maker. Notice the gain on the sale of their factory. Usually, gains and losses on assets sales are not disclosed in a separate line of the income statement. © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey Changes in Estimates and Errors When a company changes the estimates used in preparing its financial statements (like the useful life of a fixed asset), no retroactive application or cumulative effect recognized. It merely uses the new estimates prospectively. This is different from the change is accounting principle discussed above. If a company makes an error in the preparation of its financial statements (like failing to count some inventory), it merely corrects the mistake if the annual report has not yet been issued. Otherwise, it treats the error as an adjustment to opening balance of retained earnings (called a prior period adjustment). © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey The End © 1999 by Robert F. Halsey