Hume on the Problem of Evil

advertisement

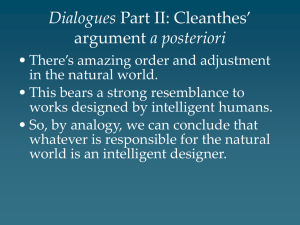

PHIL/RS 335 THE PROBLEM OF EVIL HUME’S DIALOGUE THE PROBLEM OF EVIL • The problem of evil is a challenge posed to theists committed to the claim that there is an perfectly benevolent, powerful and knowing God. • The challenge is how to explain the presence of evil in a world created by such a being. • Commonly, discussions of the problem of evil make an important distinction between types of evil. • Natural Evil: evil events or circumstances for which no agent is responsible. • Moral Evil: evil done by agents. HUME, DIALOGUES • Our reading for this time is another excerpt from Hume's Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. • At this point, Philo is conversing with Cleanthes (our old friend from the discussion of the design argument) and another interlocutor, Demea. • Demea is a natural theologian who previously had offered a version of the cosmological argument that both Cleanthes and Philo criticized. • When we pick up the discussion, Demea has just finished arguing that the best way to encourage belief in God is to ask people to reflect on the "misery and wickedness of men" (261c1). “MISERY AND WICKEDNESS” • Philo, with Demea's help, then offers a catalogue of the miseries plaguing humans. • There are external miseries, both those imposed by natural law (261c2, think of Twain's hookworm), and those imposed by human law (262c1, think of Jim Crow laws). • There are internal miseries (262c1), both those that are beyond our control (like mental illness) and those that are part of our volitional scheme (tragic errors of judgment). • Cf., the summary 262c1-2. WHAT'S THE UPSHOT? • Adopting the anthropomorphic account of Cleanthes, Philo then considers what if anything we can say about the moral situation of a theistic deity who would create and govern such a world. • His conclusion is stark (262c2-263c1). • In the context (talking to Cleanthes) he goes on to note that the problem of evil is even sharper in the context of the argument from design. THE EVIDENTIAL PROBLEM OF EVIL • The argument offered by Philo is a version of what's known as the evidential problem of evil. • The evidential problem of evil is a probabilistic argument to the effect that, though the existence of evil is not inconsistent with the existence of God, it lowers the likelihood that theism is true. • The key to the argument is the catalogue of the various forms of wickedness and suffering. • Given the vast extent of evil, of all of the various forms, it seems highly unlikely that all of it is somehow necessary or essential. • If it's not, and a theistic God could and would prevent it, it follows that it is unlikely that such a God exists. DEMEA’S RESPONSE • Demea, consistent with her cosmological perspective, offers the objection that our perspective of evil is just that, a perspective, and that what we are missing, is how it all balances out (263c2). • Philo doesn’t need to respond to this, for Cleanthes (who has already expressed his dissatisfaction with Demea's approach), offers the obvious rejoinder, that to speculate about what in principle we cannot perceive, is essentially useless, and certainly does not overwhelm what Demea has already insisted is evident and obvious to us (i.e., the presence of evil in the world). CLEANTHES’S RESPONSE • For his own sake, Cleanthes responds by just denying what both Demea and Philo have insisted, “The only method of supporting Divine benevolence, and it is what I willingly embrace, is to deny absolutely the misery and wickedness of man…And for one vexation which we meet with, we attain, upon computation, a hundred enjoyments” (264c1). • In other words, Cleanthes is trying to undercut the argument by contesting the inductive ground of the argument: the catalogue of misery and wickedness. PHILO’S RESPONSE • Philo criticizes Cleanthes's denial of the significance of the experience of evil on a number of grounds. • First, even granting what Cleanthes was insisting, though evil be less common, it is much more “violent and durable.” • Second, without granting Cleanthes’s claim, Philo notes that Cleanthes leaves an important theological concern (the moral status of God) on very shaky ground: the adequacy of Cleanthes’s judgment about the character of human experience. • Third, Cleanthes's position doesn’t even answer the question. Maybe good does outweigh evil, but why would God permit any evil whatsoever? • Thus, Philo rejects Cleanthes’s position on the problem of evil, though with more optimism than he did his advocacy of the design argument (265c2).