Design Argument - University of Arizona

advertisement

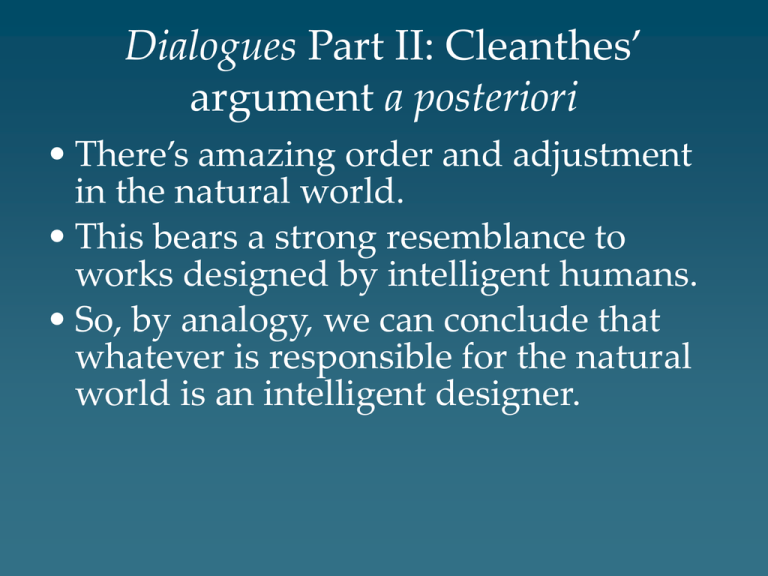

Dialogues Part II: Cleanthes’ argument a posteriori • There’s amazing order and adjustment in the natural world. • This bears a strong resemblance to works designed by intelligent humans. • So, by analogy, we can conclude that whatever is responsible for the natural world is an intelligent designer. Immediate responses • Demea: – Is this the best we can do to show God’s existence? Nothing but “experience and probability”? What about a priori demonstrations? • Philo: – This isn’t even a very good argument from experience and probability. – Such arguments are based on resemblance. And the weaker the resemblance, the weaker the argument. (Example: circulation.) – The resemblance between the universe and a house is very weak, very remote. So your argument is nothing more than “a guess, a conjecture, a presumption”. • Cleanthes: – These aren’t weak resemblances: look at the adjustment of means to ends, look at the order—this is not a stretch. Philo’s restatement of Cleanthes’ argument • Completely abstracting from experience, anything can cause anything, you can’t rule anything out. • Even upon observing the world, without a stock of experience available, you still don’t have anything to go on. – [As far as we can know a priori, order and adjustment might come from anything] • Only experience and observation can tell us what causes what. • So order and adjustment points to intelligent design only insofar as order and adjustment tends to come from intelligent design in our experience. • [That is, there’s no a priori principle that says intelligent design is the only possible explanation. It all depends on experience and observation] Philo’s restatement of Cleanthes’ argument • Experience tells us (according to Cleanthes) that matter has no internal principle of order, whereas mind does have an internal principle of order. • Of course, it’s possible a priori that matter has an internal principle of order, and that mind doesn’t. • But this is where experience comes in and tells us that the opposite is true. • So when we see order in matter, we know it must have come from mind. Philo’s objections • Now, arguments from experience work by taking previously observed cases and transfer them to currently investigated cases. • But such arguments work only if the cases are similar to each other. • You have to be extremely careful about the similarity of the cases. • It’s reckless to take data from one kind of case and transfer it to a completely different kind of case. Reckless transfer: parts to whole • Parts – We’ve learned some things about how parts of the universe operate on each other. – Nature operates by lots of different principles (intelligence, heat/cold, attraction/repulsion, ...). • Whole – But you’re trying to take what we’ve learned from observing the parts and transfer it to the whole universe. – But what about the disproportion? – And why select intelligence? There are lots of other principles available. Reckless transfer: distant parts, mature to embryonic • Distant parts – We can’t assume that nature works the same way in other distant parts of the universe. – Even here, intelligence has a very “limited sphere of action”. • Mature to embryonic – What we’ve learned concerns a finished and mature world. – We can’t transfer that to the origin of the world— who knows how nature works in such a situation! Unparalleled case • Again, arguments from experience require that the cases we’ve observed in the past bear a strong resemblance to the case currently under investigation. • But the current case is without parallel. • There can be no analogy to the origin of the universe. • We can’t use what we’ve learned from our experience to shed light on it. “Experience”? • Philo asks whether Cleanthes can seriously tell him we knows what caused the universe because of what we’ve learned from experience. • Cleanthes responds that Philo is abusing popular talk of ‘experience’, and adds that the same objections would apply to a Copernican (“Have you other earths... which you have seen to move?”) • Philo interrupts, crying out that yes, we have seen other earths: the other planets and moons. • Galileo spent a lot of time carefully establishing the similarity between other celestial bodies and the earth. • This is what a good argument from experience requires: carefully showing that we have good analogies to go on. Part III: Cleanthes strikes back • Cleanthes responds with an appeal to common sense. – He doesn’t need to establish the similarity, because it’s so obvious it strikes everyone who pays the slightest attention. – Philo’s objections are clever intellectual curiosities, but they don’t carry any weight. – They should be refuted, not head-on with intellectual grappling, but by way of examples. • So he gives two big examples to defend his argument. Voice from the clouds “Suppose, therefore, that an articulate voice were heard in the clouds, much louder and more melodious than any which human art could ever reach: Suppose, that this voice were extended in the same instant over all nations, and spoke to each nation in its own language and dialect: Suppose, that the words delivered not only contain a just sense and meaning, but convey some instruction altogether worthy of a benevolent Being, superior to mankind: Could you possibly hesitate a moment concerning the cause of this voice? and must you not instantly ascribe it to some design or purpose? Yet I cannot see but all the same objections (if they merit that appellation) which lie against the system of theism, may also be produced against this inference.” Voice from the clouds • Would you stick to your guns? – This “extraordinary voice” is without parallel, it bears no strong resemblance to human voices, ... – Perhaps it came “from some accidental whistling of the winds, not from any divine reason or intelligence” Vegetating library “But to bring the case still nearer the present one of the universe, I shall make two suppositions, which imply not any absurdity or impossibility. Suppose that there is a natural, universal, invariable language, common to every individual of human race; and that books are natural productions, which perpetuate themselves in the same manner with animals and vegetables, by descent and propagation. Several expressions of our passions contain a universal language: all brute animals have a natural speech, which, however limited, is very intelligible to their own species. And as there are infinitely fewer parts and less contrivance in the finest composition of eloquence, than in the coarsest organised body, the propagation of an Iliad or Æneid is an easier supposition than that of any plant or animal.” Vegetating library “Suppose, therefore, that you enter into your library, thus peopled by natural volumes, containing the most refined reason and most exquisite beauty; could you possibly open one of them, and doubt, that its original cause bore the strongest analogy to mind and intelligence? When it reasons and discourses; when it expostulates, argues, and enforces its views and topics; when it applies sometimes to the pure intellect, sometimes to the affections; when it collects, disposes, and adorns every consideration suited to the subject; could you persist in asserting, that all this, at the bottom, had really no meaning; and that the first formation of this volume in the loins of its original parent proceeded not from thought and design? Your obstinacy, I know, reaches not that degree of firmness: even your sceptical play and wantonness would be abashed at so glaring an absurdity.” Vegetating library • Be consistent – “But if there be any difference, Philo, between this supposed case and the real one of the universe, it is all to the advantage of the latter. The anatomy of an animal affords many stronger instances of design than the perusal of Livy or Tacitus; and any objection which you start in the former case, by carrying me back to so unusual and extraordinary a scene as the first formation of worlds, the same objection has place on the supposition of our vegetating library. Choose, then, your party, Philo, without ambiguity or evasion; assert either that a rational volume is no proof of a rational cause, or admit of a similar cause to all the works of nature.” Common sense and skepticism • I thought skeptics were only supposed to reject really complicated ‘out there’ reasoning. • When natural instincts take over, then you yield to them. • But the design argument is a “natural” and “convincing” argument. – “Consider, anatomise the eye...” • It’s your objections that are complicated and “abstruse”. • [After a bit of this, “Philo was a little embarrassed and confounded”] Demea steps in with some ‘mysticism’ • Examples with language – Your examples suggest that we could ‘enter into’ the mind of God, just as we can when we read a text. – But God’s mind is not like ours—God’s nature is incomprehensible to mere mortals. – And nature is not like an intelligible text—it “contains a great and inexplicable riddle” • Incomprehensibility – All the materials of human thought (sentiments and ideas) are designed for human life. They have no place in God’s mind. – And the manner of human thought (fluctuating and compounded) is not suitable for a perfect being. – We use ordinary terms only to praise God, not to describe him accurately. Part IV • Cleanthes questions the distinction between mystical theism and atheism. • Demea replies with the charge of anthropomorphism. • Philo presses another objection to Cleanthes’ argument a posteriori – We gain nothing by introducing a designer to explain the order and adjustment in the natural world. – After all, the designer will also be amazingly wellordered and adjusted, so this ‘explanation’ only shifts the problem back a step. Mystic = atheist? • Cleanthes levels the charge: – “[H]ow do you Mystics, who maintain the absolute incomprehensibility of the Deity, differ from sceptics or atheists, who assert, that the first cause of All is unknown and unintelligible?” – Is it just a matter of “sublime eulogies and unmeaning epithets”? • Demea returns the favor: – Name-calling, eh? How about “anthropomorphite”? – Nothing like a human mind is compatible with the “perfect immutability and simplicity, which all true theists ascribe to the Deity”. Mystic = atheist? • Cleanthes sticks to his guns: – Mystics are atheists without knowing it: your ‘God’ has no ‘mind’ at all. – “A mind, whose acts and sentiments and ideas are not distinct and successive; one, that is wholly simple, and totally immutable, is a mind which has no thought, no reason, no will, no sentiment, no love, no hatred; or, in a word, is no mind at all.” – To say that your God has a mind is an “abuse of terms”. • Philo has a little fun: – By your reasoning, you might be the only true theist in the world. – And then what happens to the argument from “the universal consent of mankind”? Philo’s new objection • There’s no gain in positing a designer – Using pure a priori reason, if an amazingly well-ordered world requires a designer, then an amazingly well-ordered designer also requires a designer. – There’s no difference between the two cases, a priori anyway. – Drawing on experience and observation, we reach the same conclusion: both minds and material bodies are delicately adjusted and ordered. • Here comes a regress – If we bring in a well-ordered mind to explain a wellordered world, then we need another well-ordered mind to explain the first. – And then we need yet another well-ordered mind. – So we’ll have a regress of Designers designing Designers. Internal principle of order? • You can say that orderly minds have an internal order to them. • But then why not say the same thing of orderly material bodies? • Sure, we have experience of minds falling into order on their own. • But we have tons of experience of material bodies falling into order on their own (generation and vegetation). • We have experience of disordered matter (death and rotting), and of disordered minds (insanity), so neither one seems to have order essentially. Empty explanations • Scholastic Aristotelians used to give empty explanations all the time. • They’d say that “bread nourished by its nutritive faculty” and that “senna purged by its purgative [faculty]”. • [Molière famously had a doctor explaining why opium put people to sleep: it’s because of its ‘virtus dormitiva’] • If you can say that order in the mind of the Designer comes from some “rational faculty”, then why can’t we also say that order in the natural world comes from some “faculty of order and proportion” Final exchange • Cleanthes: You can give a satisfactory explanation, even if you can’t explain the new stuff cited in the explanation. It’s not like explanations have to go on forever, until you reach ultimate explanations. • Philo: It’s okay to “explain particular effects by more general causes”, but there’s nothing gained in “explain[ing] a particular effect by a particular cause, which [is] no more to be accounted for than the effect itself” Part V • Philo raises another sort of objection. – In characterizing this designer, all we’re allowed to rely on is what we find in the natural world. – So we have no basis for saying the designer is infinite. – We have no basis for saying the designer is perfect (or even excellent). – We have no basis for saying there’s only one designer. – We have no basis for saying the designer is immortal. – We have no reason not to completely anthropomorphize the designer. • You can’t base your theology on this argument. Part VI • Philo offers another hypothesis – Cleanthes reasons from experience and concludes that, since the natural world is like a machine, it comes from something like intelligent design. – But there are other hypotheses available. – Why not conclude that, since the world is like an animal, it comes from something like generation? • Cleanthes responds with some worries about the age of the earth. Part VII • Philo offers another hypothesis – The universe is like a living thing, so it comes from something like vegetation or generation. – This is even better than the intelligent design hypothesis. • Demea raises worries for this hypothesis – Can Philo explain how this vegetation and generation works? – Wouldn’t a vegetating universe itself be a remarkable argument for intelligent design? Philo, shifting the challenge • Cleanthes’ two presuppositions – Our experience favors a ‘machine-design analogy’. – And we can take our experience as a guide to the universe as a whole. • Philo moves from the second to the first – He’s now (for the sake of argument) allowing the second (“But to waive all objections drawn from this topic…”) – Instead, he’s going to challenge the first—our experience offers even more support for a ‘organismreproduction analogy’. – That is, even in our limited experience, order and adjustment are found to result from natural processes at least as much as from intelligent design. Demea’s objections, Philo’s replies • Demea: But how could a world come from vegetation or generation? • Philo: We can say that the universe is like a “great vegetable” producing world-seeds. Or that it’s like an animal laying eggs. • Demea: But how can you take plant and animal life as a guide to the universe as a whole? These are completely different kinds of cases. • Philo: That’s what I’ve been saying! But if you do want to take our limited experience as a guide, then we’ve got no other standard besides resemblance. • Demea: Can you explain how vegetation or generation work? • Philo: As well as Cleanthes can explain how intelligent design works. We don’t have any insight into the various operations used by nature. We only know their effects. Demea’s objections, Philo’s replies • Demea: But if order arises from vegetation, isn’t that very fact evidence of intelligent design? • Philo: No; order comes from purely natural processes all the time. If you insist that these ultimately come from intelligent design, then you’re begging the question. • Philo, cont’d: Moreover, if you insist on a further explanation for vegetation producing order, then I’ll insist on a further explanation for intelligent design producing order. Cleanthes said, “We’ve got to stop somewhere,” because otherwise we’re off on a regress. – Indeed, generation has advantages over reason: in our experience, reason always comes from generation, never the other way around. Philo sums up “Compare, I beseech you, the consequences on both sides. The world, say I, resembles an animal; therefore it is an animal, therefore it arose from generation. The steps, I confess, are wide; yet there is some small appearance of analogy in each step. The world, says Cleanthes, resembles a machine; therefore it is a machine, therefore it arose from design. The steps are here equally wide, and the analogy less striking. And if he pretends to carry on my hypothesis a step farther, and to infer design or reason from the great principle of generation, on which I insist; I may, with better authority, use the same freedom to push farther his hypothesis, and infer a divine generation or theogony from his principle of reason. I have at least some faint shadow of experience, which is the utmost that can ever be attained in the present subject. Reason, in innumerable instances, is observed to arise from the principle of generation, and never to arise from any other principle.” Part VIII • Philo offers one more hypothesis – The Epicurean hypothesis: an infinite series of different arrangements of particles. • And then a variation – It cycles through lots of different disorderly arrangements. – When an orderly arrangement shows up, it ‘sticks’. • Cleanthes raises some worries concerning advantageous traits in living things. • Philo admits that any positive hypothesis concerning the origin of worlds has serious problems—which is a victory for skepticism. Reviving the Epicurean hypothesis • Philo says he can make up all sorts of hypotheses – Given “the nature of the subject”, there’s no limit to the number of wild hypotheses that can be dreamed up. – So he’ll revive “the most absurd system” ever: the Epicurean hypothesis. • The Epicurean hypothesis – A finite number of particles goes through a series of arrangements. – Given an infinite number of arrangements, it’s guaranteed that something beautiful and orderly and well-adjusted will show up eventually. – Demea protests that this involves matter acquiring motion on its own. – Philo replies that there’s nothing impossible about that, and that experience shows lots of cases where (as far as we know) matter is in motion on its own, without any agent responsible (or maybe motion has always been going on). A variation on the Epicurean hypothesis • Order that ‘sticks’ – Suppose that an orderly arrangement would preserve itself in order. – If so, then once the cycling series of disorderly arrangements reached an orderly arrangement, it would stay that way. – And it would look just like design. – It would be useless to insist on how welldesigned living things are—how could they stay alive unless they were so well-designed? – [A lot of people see a foreshadowing of Darwin in this passage] An exchange between Cleanthes and Philo • Cleanthes: But why are there so many “conveniences and advantages” in the natural world? These aren’t necessary for the mere preservation of the species. • Philo: All hypotheses about the origin of the world have problems. Look at yours: – In our experience, ideas are copied from objects, not vice versa. – In our experience, thought has influence on matter only when it’s intimately connected with it. – In our experience, things with minds eventually die. • Philo, cont’d: So we should be careful about condemning each other. None of us knows for sure.