Moral Diplomacy

advertisement

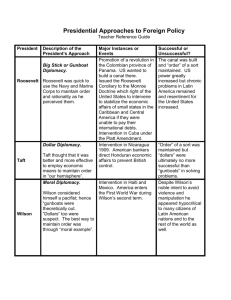

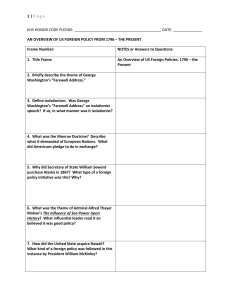

American Foreign Policy Name: ______________________________________ Period: _______ Date: ____________________ Directions: Use your textbook as well as your classroom notes to complete the chart below. Foreign policy Created By Summary of the Policy Neutrality Big Stick Diplomacy Dollar Diplomacy Moral Diplomacy Good NeighborPolicy Question: In your opinion, which course of action was best suited for the United States as they entered the 20th century? Defend youranswer. Maintaining U.S. Neutrality On 28 July, 1914, World War I began with the AustroHungarian invasion of Serbia, followed by the German invasion of Belgium, Luxembourg, and France and a Russian attack against Germany. However, the U.S. did not join the conflict until April 1917. For two and a half years after the outbreak of the war in Europe, President Wilson attempted to keep the U.S. neutral. The United States pursued a policy of noninterventionism, avoiding conflict while trying to broker a peace. The U.S. government, under Wilson's firm control, called for neutrality "in thought and deed. " Apart from an Anglophile element supporting the British, public opinion went along with neutrality at first . The sentiment was strong for neutrality among the Irish Americans, German Americans, and Swedish Americans and many farmers (especially in the South), church leaders, and women. "Hurting their feelings" Political cartoon showing British characters crying as American warships sit in the harbor, maintaining neutrality in in the European conflict. However, the citizenry increasingly came to see Germany as the villain after news of atrocities in Belgium in 1914 and the sinking of the passenger liner RMS Lusitania in 1915 in defiance of international law. Wilson made all the key decisions and kept the economy on a peacetime basis, while allowing large-scale loans to Britain and France. To preclude making any military threat, Wilson made no preparations for war and kept the army on its small, peacetime basis despite increasing demands for preparedness. Big Stick Diplomacy Big Stick policy, in American history, policy popularized and named by Theodore Roosevelt that asserted U.S. domination when such dominance was considered the moral imperative. Roosevelt’s first noted public use of the phrase occurred when he advocated before Congress increasing naval preparation to support the nation’s diplomatic objectives. Earlier, in a letter to a friend, while he was still the governor of New York, Roosevelt cited his fondness for a West African proverb, “Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.” The phrase was also used later by Roosevelt to explain his relations with domestic political leaders and his approach to such issues as the regulation of monopolies and the demands of trade unions. The phrase came to be automatically associated with Roosevelt and was frequently used by the press, especially in cartoons, to refer particularly to his foreign policy; in Latin America and the Caribbean, he enacted the Big Stick policy (in foreign policy, also known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine) to police the small debtor nations that had unstable governments. Dollar Diplomacy, 1909–1913 From 1909 to 1913, President William Howard Taft and Secretary of State Philander C. Knox followed a foreign policy characterized as “dollar diplomacy.” William Howard Taft Taft shared the view held by Knox, a corporate lawyer who had founded the giant conglomerate U.S. Steel, that the goal of diplomacy was to create stability and order abroad that would best promote American commercial interests. Knox felt that not only was the goal of diplomacy to improve financial opportunities, but also to use private capital to further U.S. interests overseas. “Dollar diplomacy” was evident in extensive U.S. interventions in the Caribbean and Central America, especially in measures undertaken to safeguard American financial interests in the region. In China, Knox secured the entry of an American banking conglomerate, headed by J.P. Morgan, into a European-financed consortium financing the construction of a railway from Huguang to Canton. In spite of successes, “dollar diplomacy” failed to counteract economic instability and the tide of revolution in places like Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and China. Moral Diplomacy Moral Diplomacy is a form of Diplomacy proposed by US President Woodrow Wilson in his 1912 election. Moral Diplomacy is the system in which support is given only to countries whose moral beliefs are analogous to that of the nation. This promotes the growth of the nation's ideals and damages nations with different ideologies. [1] It was used by Woodrow Wilson to support countries with democratic governments and to economically injure non-democratic countries (seen as possible threats to the U.S.). He also hoped to increase the number of democratic nations, particularly in Latin America.[2] Conception Woodrow Wilson was of the firm belief that democracy is the most essential aspect of a stable and prospering nation. He also believed that the United States had to play the pioneering role in promoting democracy and peace throughout the world. Several nations, especially in Latin-America, were under the influence of imperialism, something that Wilson opposed. In order to curb the growth of imperialism, and spread democracy, Wilson came up with the idea of moral diplomacy. Wilson’s moral diplomacy replaced the dollar diplomacy of William Howard Taft, which highlighted the importance of economic support to improve bilateral ties between two nations. Taft’s dollar diplomacy was based on economic support, while Wilson’s moral diplomacy was based on economic power.[3] American Exceptionalism Main article: American exceptionalism Many of Woodrow Wilson's ideas about moral diplomacy and America's role in the world come from American exceptionalism. American exceptionalism is the proposition that the United States is different from other countries in that it has a specific world mission to spread liberty and democracy. [4] In this view, America's exceptionalism stems from its emergence from a revolution and developing a uniquely American ideology, based on liberty, egalitarianism, individualism, populism and laissez-faire. This observation can be traced to Alexis de Tocqueville, the first writer to describe the United States as "exceptional" in 1831 and 1840.[5] In Woodrow Wilson's 1914 address on "The Meaning of Liberty" he stated alludes to Americas potential to be "the light which will shine unto all generations and guide the feet of mankind to the goal of justice and liberty and peace"[6] and he later puts those ideas into action through moral diplomacy. Good Neighbor policy - Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas (left) and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (right) in 1936 The Good Neighbor policy was the foreign policy of the administration of United States President Franklin Roosevelt towards Latin America. Although the policy was implemented by the Roosevelt administration, 19th-century politician Henry Clay paved the way for it and coined the term "Good Neighbor". The policy's main principle was that of non-intervention and non-interference in the domestic affairs of Latin America. It also reinforced the idea that the United States would be a “good neighbor” and engage in reciprocal exchanges with Latin American countries.[1] Overall, the Roosevelt administration expected that this new policy would create new economic opportunities in the form of reciprocal trade agreements and reassert the influence of the United States in Latin America; however, many Latin American governments were not convinced.[2] Background - In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the United States periodically intervened militarily in Latin American nations to protect its interests, particularly the commercial interests of the American business community. After Roosevelt Corollary of 1904 whenever the United States felt its debts were not being repaid in a prompt fashion, its citizens' business interests were being threatened, or its access to natural resources were being impeded, military intervention or threats were often used to coerce the respective government into compliance. This made many Latin Americans wary of U.S. presence in their region and subsequently hostilities grew towards the United States. FDR administration - In an effort to denounce past U.S. interventionism and subdue any subsequent fears of Latin Americans, Roosevelt announced on March 4, 1933, during his inaugural address that: "In the field of World policy, I would dedicate this nation to the policy of the good neighbor, the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others, the neighbor who respects his obligations and respects the sanctity of his agreements in and with a World of neighbors."[3] In order to create a friendly relationship between the United States and Central as well as South American countries, Roosevelt sought to stray from asserting military force in the region.[4] This position was affirmed by Cordell Hull, Roosevelt's Secretary of State at a conference of American states in Montevideo in December 1933. Hull said: "No country has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another".[5] Roosevelt then confirmed the policy in December of the same year: "The definite policy of the United States from now on is one opposed to armed intervention".[6]