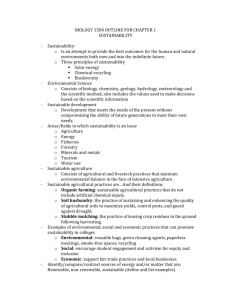

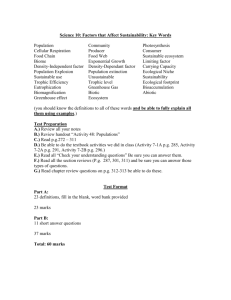

Chapter 20 Sustainability, Economics, and Equity - My Site

advertisement