report - Evaluation Resource Center

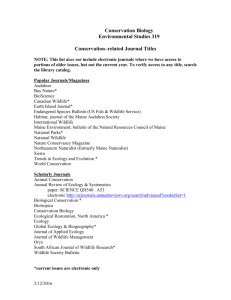

advertisement