File

advertisement

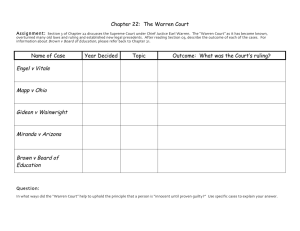

SUPREME COURT OPINIONS: The Warren Court (1953 - 1969) 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas Chief Justice Earl Warren Held that racial segregation in public education, even in comparable facilities, violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, in effect, that "separate but equal" is unconstitutional. Brown held "separate" inherently unequal and specifically overruled Plessy v. Ferguson. The following year, Brown II established the framework for remedying segregation in education, though the process would take decades, and still falls short of completion. 1961 Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 J. Tom C. Clark, C.J. Warren, J. Frankfurter, J. Brennan, J. Whittaker Concurrance: J. Hugo Black Concurrance: J. William O. Douglas Separate: J. Potter Stewart Dissent: J. John Marshall Harlan Mapp stems from the warrantless, and therefore illegal, search of Mapp's residence resulting in the discovery of lewd material, for possession of which she was prosecuted and found guilty. Although the primary question before the Court was the constitutionality of Ohio's law against possessing such materials, the majority chose to decide the case on a secondary issue: whether the exclusionary rule, which prevented the use a trial of evidence gained in violation of the 4th Amendment, and which applied to federal courts, should be applied to state courts. Just twelve years earlier, the Court had considered that question in Wolf v. Colorado, and decided that while the 4th Amendment applied to the states, the exclusionary rule did not. It was the Court's intention to revisit that decision. Citing the 1914 case, Weeks v. U.S., which had applied the exclusionary rule to federal courts, Clark matched the 4th Amendment's prohibition of illegal search and seizure with the 5th Amendments right against self- incrimination, writing: "If letters and private documents can thus be seized and held and used in evidence against a citizen accused of an offense, the protection of the Fourth Amendment declaring his right to be secure against such searches and seizures is of no value, and, so far as those thus placed are concerned, might as well be stricken from the Constitution." It was Clark's opinion that if the 4th Amendment applied to the states, as Wolf said it did, then the exclusionary rule must also, and for the same reason as in federal courts — without the rule the right would be meaningless. That fact alone made it more than a judicial "remedy" and turned it into a constitutional principle; a critical difference, because while the court could impose constitutional principles on the states, it had no power to make what amounted to a mere "rule of evidence" for their courts. Black drew the linkage between the 4th and 5th even more sharply. While the exclusionary rule was in one part remedy against the use of evidence improperly gained under the 4th; it was the 5th that gave it the stature of a constitutional principle, since illegally seized evidence was tantamount to a forced confession — a violation of the citizens right against self-incrimination. He also argued that a broad interpretation of constitutional protections of persons and property was the only way to preserve them. He finally pointed out that, from a practical aspect, the exclusionary rule was a clearer and more certain guideline to what could be used as evidence under questionable circumstances than the Court's prior "shocks the conscience" rule. Douglas' opinion basically followed Clark's, though he seemed to be less concerned whether the exclusionary rule was remedy — though he found it superior to all others — or principle. Stewart avoided the entire controversy and ruled on the original question, finding that Mapp's conviction for possession of lewd materials was an unconstitutional violation of her 1st Amendment rights as applied to the states by the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. 1962 Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 Justice Hugo Black, C. J. Warren, J. Clark, J. Harlan, J. Brennan Concurrence: Justice William O. Douglas Dissent: Justice Potter Stewart J.J. Frankfurter and White did not participate in the decision In Engle the Court found that a state-composed prayer recited in public schools, even though it was non-deniminational, and even though no child was required to participate in it, was unquestionably a religious exercise and therefore a clear violation of the religious establishment clause of the 1st Amendment. In writing the decision, Black first pointed out that no party in the case had denied that the prayer was religious; in fact, all had admitted it. He next pointed out that the fact that it was nondenominational and voluntary was irrelevant — the former didn't make it less religious, and the latter didn't make it less of an establishment. He wrote: "The Establishment Clause...does not depend upon any showing of direct governmental compulsion and is violated by the enactment of laws which establish an official religion whether those laws operate directly to coerce nonobserving individuals or not." He finally noted that the separation of church and state was intended by the Founders to protect both. Concurring, Douglas went futher than Black on the question of voluntariness: "...no matter how briefly the prayer is said...the person praying is a public official on the public payroll, performing a religious exercise in a governmental institution. It is said that the element of coercion is inherent in the giving of this prayer. If that is true here, it is also true of the prayer with which this Court is convened, and of those that open the Congress. Few adults, let alone children, would leave our courtroom or the Senate or the House while those prayers are being given. Every such audience is in a sense a "captive" audience." In what may be called a nod to reality, Douglas underscored the inherently coercive nature of even voluntary prayer. 1963 Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 Justice Hugo Black Separate: Justice William O. Douglas Concurrence in Result: Justice Tom Clark Concurrence: Justice John Marshall Harlan Gideon extended the right to counsel in non-capital cases — incumbent on the federal government through the Sixth Amendment — to the states. In writing for the Court, Black simply concluded that the "due process" required of the states by the Fourteenth Amendment had to include the Sixth Amendment's right to counsel. He wrote,"...reason and reflection, require us to recognize that, in our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him. This seems to us to be an obvious truth." Black's opinion reflected his own view that the 14th Amendment incorporated the entire Bill of Rights and applied it to the states. Clark's concurrence rejected the distinction between capital cases, where counsel had previously been required, and non-capital cases, for which Gideon created that requirement: "I must conclude...that the Constitution makes no distinction between capital and noncapital cases. The Fourteenth Amendment requires due process of law for the deprival of "liberty," just as for deprival of "life," and there cannot constitutionally be a difference in the quality of the process based merely upon a supposed difference in the sanction involved." Harlan, ever the conservative, made it quite clear that his concurrence was based on what he saw as the slow evolution of the Court toward the Gideon result. Moreover, he was careful to point out that: "When we hold a right or immunity, valid against the Federal Government, to be [essential to due process] and thus valid against the States, I do not read our past decisions to suggest that, by so holding, we automatically carry over an entire body of federal law and apply it in full sweep to the States...In what is done today, I do not understand the Court to...embrace the concept that the Fourteenth Amendment "incorporates" the Sixth Amendment as such." In his very brief separate opinion, Douglas took square aim at the latter view of Harlan: "My Brother HARLAN is of the view that a guarantee of the Bill of Rights that is made applicable to the States by reason of the Fourteenth Amendment is a lesser version of that same guarantee as applied to the Federal Government...But that view has not prevailed, and rights protected against state invasion by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment are not watered-down versions of what the Bill of Rights guarantees." 1964 Heart of Atlanta Hotel Inc. v. United States, 379 U.S. 421 Justice Tom C. Clark, C.J. Warren, J. Harlan, J. Brennan, J Stewart, J. White Concurrance: J. Hugo L. Black Concurrance: J. William O. Douglas Concurrance: J. Arthur J. Goldberg The case arose as a challenge by the Heart of Atlanta Hotel, which in the course of its business refused accomodations to blacks, to the right of the federal government to end its discriminatory practices through the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Particularly, it challenged the idea that such a prohibition could be accomplished through Congress' powers under the Commerce Clause (Art. I, § 8, cl. 3) of the Constitution, on which the Civil Rights Act was based. Writing for the majority, Clark found that Congress did have such power under the Commerce Clause. While agreeing that commerce occuring within a single state was beyond Congress' power to regulate, the Heart of Atlanta's business included out-of-state guests — for whom it actively advertised. Its effect on commerce was the burden it, and businesses like it, placed on an entire class of individuals traveling interstate; an activity clearly falling within Congress' commerce power. To the objection that Congress was actually stretching its commerce power to right a moral, not an economic problem, Clark countered that Congress' motives were secondary to the fact that since Gibbons v. Ogden in 1824 Congress' power over interstate commerce was plenary. Black's concurrence echoed Clark, but added two things. The first was Ollie's Barbeque, a second challenger to the Act which, though its clientele was almost exclusively local, Black found to be within the power of the Act because it purchased a substantial portion of its supplies — mostly beef — from outside of Georgia. Second, Black pointed out that along with the Commerce Clause, which allowed Congress to regulate interstate commerce, came the Necessary and Proper Clause (Art. I, § 8, cl. 18) which allowed Congress to regulate a purely single-state activity if iteffected interstate commerce. Thus, direct ties to interstate commerce weren't necessary to bring a discriminating business within the requirements of the Act. Concurring, Douglas agreed with the judgment of the majority, but was dissatisfied with its reasoning. He argued that the Commerce Clause did, indeed, give Congress power to enforce the Act, pointing out that Congress had chosen that particular constitutional foundation to avoid the implications of the 1883 Civil Rights Cases in which the Court had denied Congress the right to enforce the "equal protection" clause of the 14th Amendment against private individuals and businesses, since the 14th Amendment applied only to the states, their actions and agents. Arguing that the Commerce Clause didn't cover enough, and would leave the door at least ajar to continuing discrimination, he urged a return to the 14th Amendment, reasoning that discrimination, even by private entities, did involve state action through the enforcement of trespass and other laws against blacks attempting to purchase goods, service and accomodations. In short, the states violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment when they assisted private businesses in discrimination, and therefore left themselves open to Congressional regulation. 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 489 Justice William O. Douglas Concurrance: J. Arthur Goldberg, C.J. Warren, J. Brennan Concurrance in Judgment: J. John Marshall Harlan Concurrance in Judgment: J. Byron White Dissent: J. Hugo Black, J. Stewart Dissent: J. Potter Stewart, J. Black Griswold held unconstitutional a Connecticut law, intended to prevent adultery and promiscuity, which banned the the use of contraceptives, and which also made illegal the aiding or abeting such use. The appellant, Griswold, was Executive Director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut, and was arrested under the law for providing contraception to a married client. He challenged his conviction as unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. Wrining for the Court, Douglas focused on the rights of the married couple, not those of Griswold: theirs had been the crime that Griswold had only abetted. Citing precedent, he showed that the Court had frequently found rights which, though not specifically enumerated in the Constitution, nonetheless logically flowed from them, and which gave them meaning. These existed as a sort of supertext behind the specifics of the Bill of Rights. Douglas called them "penumbras" and wrote, "...specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance." Among these unenumerated rights, derived mainly from the 1st Amendment, but also from the 3rd, 4th and 5th, was the right to privacy. Douglas backed this right with the 9th Amendment's guarantee of unenumerated rights, and applied it to the states through the fourteenth. Finally, within this protected "zone of privacy" Douglas squarely placed marriage, concluding that the Connecticut statute, "...cannot stand in light of the familiar principle, so often applied by this Court, that a governmental purpose to control or prevent activities constitutionally subject to state regulation may not be achieved by means which sweep unnecessarily broadly and thereby invade the area of protected freedoms." Concurring, Goldberg relied even more heavily on the 9th: "The Ninth Amendment simply shows the intent of the Constitution's authors that other fundamental personal rights should not be denied such protection or disparaged in any other way simply because they are not specifically listed in the first eight constitutional amendments." Further, like Douglas, Goldberg applied the "substantive due process" theory to the 14th Amendment: certain rights — ones not always clearly enumerated — generally were so fundamental, or had through time become so fundamental, that they required judicial recognition and application. Goldberg found privacy to be among such rights, and he concluded that Connecticut's purpose in having the law to be far out-weighed by its intrusion on the privacy rights of married couples. Harlan concurred only in the result, not in the reasoning of the majority. Unlike many of the other justices who wrestled with the extent to which the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment actually applied the Bill of Rights to the states, Harlan argued that Due Process was more than a conduit for the first ten amendments, but stood on its own, founded on "...basic values 'implicit in the concept of ordered liberty...'" He wrote, "While the relevant inquiry may be aided by resort to one or more of the provisions of the Bill of Rights, it is not dependent on them or any of their radiations. The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment stands, in my opinion, on its own bottom." He concluded that the statute did indeed violate basic values. White, too, concurred in the result but not the reasoning. Avoiding the larger issue of privacy, White focused on precedents establishing rights surrounding marriage and family, found that those rights were protected by the 14th Amendment, and concluded that the Connecticut statute served no rational purpose that justified their infringment. 1966 Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 Chief Justice Earl Warren, J. Black, J. Douglas, J. Brennan, J. Fortas Concurrence and Dissent: J. Tom C. Clark Dissent: J. John Marshall Harlan, J. Stewart, J. White Dissent: J. Byron R. White, J. Harlan, J. Stewart In Miranda the Court specifically brought the police interrogation room within the Fifth Amendment's right against self-incrimination — not done since the Bram decision in 1897and gave rise to the socalled "Miranda" rights. The four cases falling under Miranda all involved confessions made during police interrogation. The question for the Court was whether the suspects in those cases made those statements voluntarily and in full knowledge of their Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. Warren concluded that while "...we might not find the defendants' statements to have been involuntary in traditional terms...", the circumstances under which they were made — incommunicado, custodial police interrogation, and the atmosphere of intimidation that went with it — made them presumptively involuntary. He wrote: "Unless adequate protective devices are employed to dispel the compulsion inherent in custodial surroundings, no statement obtained from the defendant can truly be the product of his free choice. From the foregoing, we can readily perceive an intimate connection between the privilege against self-incrimination and police custodial questioning." The protective device mandated by the decision was to guarantee that suspects were first fully informed of their rights — to remain silent and to counsel — before any questioning began, and that questioning should cease should the suspect choose to exercise those rights. Thus the Miranda decision created a "bright line" rule based on a pre-interrogation "reading of rights" to suspects without which no subsequent statement could be considered voluntary. As for the connection between self-incrimination and interrogation, Warren answered the charge from dissent that the Fifth Amendment only applied to testimony at trial, not to interrogation, by pointing out that statements brought to trial from interrogation were as incriminating as anything said in open court, and in the case of confessions, more so. The guarantee was meaningless if it did not apply to interrogation: "Without the protections flowing from adequate warnings and the rights of counsel, all the careful safeguards erected around the giving of testimony...would become empty formalities in a procedure where the most compelling possible evidence of guilt, a confession, would have already been obtained at the unsupervised pleasure of the police..." 1967 Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 Chief Justice Earl Warren, J. Black, J. Douglas, J. Clark, J. Harlan, J. Brennan, J. White, J. Fortas Concurrence: Justice Potter Stewart The decision stems from the marriage of two Virginia residents, Mildred Jeter, a black woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, in the District of Columbia — where their marriage was legal — and their return to Virginia — where it was not. They were prosecuted under Virginia's anti-miscegenation law which prohibited marriage between whites and members of another race. The trial judge sentenced them to a year in prison, but suspended the sentence provided the couple leave the state for 25 years. Their appeals eventually came before the Court. The question came to revolve around the 14th Amendment and its Equal Protection clause. Virginia argued that since the law, and the penalty, applied equally to both whites and blacks there was no equal protection problem. The Court disagreed. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Warren pointed out that where the state's position might otherwise be valid, the issue of distinctions drawn on the basis of race was too weighty a matter to let pass on the basis of equal application: "In the case at bar, however, we deal with statutes containing racial classifications, and the fact of equal application does not immunize the statute from the very heavy burden of justification which the Fourteenth Amendment has traditionally required of state statutes drawn according to race."Further on in the decision, he went on to say: "At the very least, the Equal Protection Clause demands that racial classifications, especially suspect in criminal statutes, be subjected to the "most rigid scrutiny,"...and, if they are ever to be upheld, they must be shown to be necessary to the accomplishment of some permissible state objective, independent of the racial discrimination which it was the object of the Fourteenth Amendment to eliminate. Indeed, two members of this Court have already stated that they cannot conceive of a valid legislative purpose . . . which makes the color of a person's skin the test of whether his conduct is a criminal offense." For the Court, Virginia's stated purposes for the statute — ""to preserve the racial integrity of its citizens," and to prevent "the corruption of blood," "a mongrel breed of citizens," and "the obliteration of racial pride,"" — clearly fell short of adequate justification, especially as the statute only prohibited intermarriage with whites, which the Court correctly identified as "...an endorsement of the doctrine of White Supremacy." Finally, calling marriage "...one of the "basic civil rights of man...", Warren concluded that the Virginia statute also violated the couples' due process rights by denying them a fundamental liberty without due process of law. 1969 Brandenburg v. Ohio Per Curiam Established that even speech advocating violence, so long as it is not "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action", is constitutionally protected.