Kosovar Albanian Identity within Migration in the Swedish society

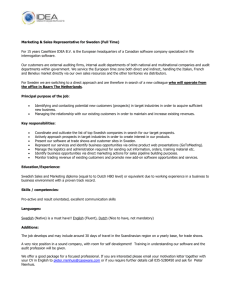

advertisement