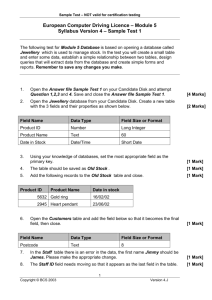

223_103_Final - Department of Computer Science

advertisement

Database Principles-CS 257

Deepti Bhardwaj

Roll No. 223_103

SJSU ID:

006521307

CS 257 – Dr.T.Y.Lin

13.1.1 The Memory Hierarchy

Several components for data storage having different data

capacities available

Cost per byte to store data also varies

Device with smallest capacity offer the fastest speed with

highest cost per bit

Cache

Lowest level of the hierarchy

Data items are copies of certain locations of main

memory

Sometimes, values in cache are changed and

corresponding changes to main memory are delayed

Machine looks for instructions as well as data for

those instructions in the cache

Holds limited amount of data

Memory Hierarchy Diagram

Programs,

Main Memory DBMS

DBMS

Tertiary Storage

As Visual Memory

System

Disk

Main Memory

Cache

File

13.1.1 The Memory Hierarchy con’t

No need to update the data in main memory immediately

in a single processor computer

In multiple processors data is updated immediately to

main memory is called as write through

Main Memory

Everything happens in the computer i.e. instruction

execution, data manipulation, as working on information

that is resident in main memory

Main memories are random access one can obtain any

byte in the same amount of time

In the center of the action is the computer's main

memory. We may think of everything that happens

in the computer - instruction executions and data

manipulations - as working on information that is

resident in main memory

Typical times to access data from main memory to

the processor or cache are in the 10-100

nanosecond range

Secondary Storage

Used to store data and programs when they are not

being processed

More permanent than main memory, as data and

programs are retained when the power is turned off

E.g. magnetic disks, hard disks

Essentially every computer has some sort of

secondary storage, which is a form of storage that

is both significantly slower and significantly more

capacious than main memory.

The time to transfer a single byte between disk

and main memory is around 10 milliseconds.

Tertiary Storage

Holds data volumes in terabytes

Used for databases much larger than what can be stored

on disk

As capacious as a collection of disk units can be,

there are databases much larger than what can be

stored on the disk(s) of a single machine, or even

of a substantial collection of machines.

Tertiary storage is characterized by significantly

higher read/write times than secondary storage,

but also by much larger capacities and smaller cost

per byte than is available from magnetic disks.

13.1.2 Transfer of Data between Levels

Data moves between adjacent levels of the hierarchy

At the secondary or tertiary levels accessing the desired

data or finding the desired place to store the data takes

a lot of time

Disk is organized into bocks

Entire blocks are moved to and from memory called a

buffer

A key technique for speeding up database operations is

to arrange the data so that when one piece of data block

is needed it is likely that other data on the same block

will be needed at the same time

Same idea applies to other hierarchy levels

13.1.3 Volatile and Non Volatile Storage

A volatile device forgets what data is stored on it after

power off

Non volatile holds data for longer period even when

device is turned off

All the secondary and tertiary devices are non volatile

and main memory is volatile

13.1.4 Virtual Memory

Typical software executes in virtual memory

When we write programs the data we use,

variables of the program, files read and so on

occupies a virtual memory address space.

Address space is typically 32 bit or 232 bytes or 4GB

The Operating System manages virtual memory,

keeping some of it in main memory and the rest on

disk.

Transfer between memory and disk is in terms of blocks.

13.2.1 Mechanism of Disk

Mechanisms of Disks

Use of secondary storage is one of the important

characteristic of DBMS

Consists of 2 moving pieces of a disk

1. disk assembly

2. head assembly

Disk assembly consists of 1 or more platters

Platters rotate around a central spindle

Bits are stored on upper and lower surfaces of

platters

Disk is organized into tracks

The track that are at fixed radius from center form one

cylinder

Tracks are organized into sectors

Tracks are the segments of circle separated by gap

A typical disk format from the text book

is shown as below:

13.2.2 Disk Controller

One or more disks are controlled by disk controllers

Disks controllers are capable of

Controlling the mechanical actuator that moves the

head assembly

Selecting the sector from among all those in the

cylinder at which heads are positioned

Transferring bits between desired sector and main

memory

Possible buffering an entire track

Selecting a surface from which to read or write,

and selecting a sector from the track on that

surface that is under the head.

An example of single processor is shown in next

slide.

Simple computer system from the text

is shown below:

13.2.3 Disk Access Characteristics

Accessing (reading/writing) a block requires 3 steps

Disk controller positions the head assembly at the

cylinder containing the track on which the block is

located. It is a ‘seek time’

The disk controller waits while the first sector of the

block moves under the head. This is a ‘rotational

latency’

All the sectors and the gaps between them pass the

head, while disk controller reads or writes data in

these sectors. This is a ‘transfer time’

The sum of the seek time, rotational latency,

transfer time is the latency of the time.

13.3 Accelerating Access to Secondary

Storage

Several approaches for more-efficiently accessing data in

secondary storage:

Place blocks that are together in the same cylinder.

Divide the data among multiple disks.

Mirror disks.

Use disk-scheduling algorithms.

Pre fetch blocks into main memory.

Scheduling Latency – added delay in accessing data

caused by a disk scheduling algorithm.

Throughput – the number of disk accesses per second

that the system can accommodate.

13.3.1 The I/O Model of Computation

The number of block accesses (Disk I/O’s) is a good

time approximation for the algorithm.

This should be minimized.

Ex 13.3: You want to have an index on R to identify the

block on which the desired tuple appears, but not where

on the block it resides.

For Megatron 747 (M747) example, it takes 11ms to

read a 16k block.

A standard microprocessor can execute millions of

instruction in 11ms, making any delay in searching

for the desired tuple negligible.

13.3.2 Organizing Data by Cylinders

If we read all blocks on a single track or cylinder

consecutively, then we can neglect all but first seek time

and first rotational latency.

Ex 13.4: We request 1024 blocks of M747.

If data is randomly distributed, average latency is

10.76ms by Ex 13.2, making total latency 11s.

If all blocks are consecutively stored on 1 cylinder:

6.46ms + 8.33ms * 16 = 139ms

(1 average seek) (time per rotation)

(# rotations)

13.3.3 Using Multiple Disks

If we have n disks, read/write performance will increase

by a factor of n.

Striping – distributing a relation across multiple disks

following this pattern:

Data on disk R1: R1, R1+n, R1+2n,…

Data on disk R2: R2, R2+n, R2+2n,…

…

Data on disk Rn: Rn, Rn+n, Rn+2n, …

Ex 13.5: We request 1024 blocks with n = 4.

6.46ms + (8.33ms * (16/4)) = 39.8ms

(1 average seek) (time per rotation)

(# rotations)

13.3.4 Mirroring Disks

Mirroring Disks – having 2 or more disks hold identical

copied of data.

Benefit 1: If n disks are mirrors of each other, the

system can survive a crash by n-1 disks.

Benefit 2: If we have n disks, read performance

increases by a factor of n.

Performance increases further by having the controller

select the disk which has its head closest to desired data

block for each read.

13.3.5 Disk Scheduling and the Elevator

Problem

Disk controller will run this algorithm to select which of

several requests to process first.

Pseudo code:

requests[] // array of all non-processed data

requests

upon receiving new data request:

requests[].add(new request)

while(requests[] is not empty)

move head to next location

if(head location is at data in requests[])

retrieve data

remove data from requests[]

if(head reaches end)

reverse head direction

13.3.6 Prefetching and Large-Scale

Buffering

If at the application level, we can predict the order

blocks will be requested, we can load them into main

memory before they are needed.

13.4 Disk Failure - Types of Errors

Intermittent Error: Read or write is unsuccessful.

Media Decay: Bit or bits becomes permanently

corrupted.

Write Failure: Neither write or retrieve the data.

Disk Crash: Entire disk becomes unreadable.

13.4.1 Intermittent Failures

The most common form of failure.

If we try to read the sector but the correct content of that

sector is not delivered to the disk controller

Check for the good or bad sector

To check write is correct: Read is performed

Good sector and bad sector is known by the read operation

Parity checks can be used to detect this kind of

failure.

When we try to read a sector, but the correct

content of that sector is not delivered to the disk

controller.

If the controller has a way to tell that the sector is

good or bad (checksums), it can then reissue the

read request when bad data is read.

Media Decay

Serious form of failure.

Bit/Bits are permanently corrupted.

Impossible to read a sector correctly even after many

trials.

Stable storage technique for organizing a disk is used to

avoid this failure.

Write failure

Attempt to write a sector is not possible.

Attempt to retrieve previously written sector is

unsuccessful.

Possible reason – power outage while writing of the

sector.

Stable Storage Technique can be used to avoid this.

Disk Crash

Most serious form of disk failure.

Entire disk becomes unreadable, suddenly and

permanently.

RAID techniques can be used for coping with disk

crashes.

13.4.2 Checksums

Technique used to determine the good/bad status

of a sector.

Each sector has some additional bits, called the

checksums

Checksums are set on the depending on the values of

the data bits stored in that sector

Probability of reading bad sector is less if we use

checksums

For Odd parity: Odd number of 1’s, add a parity bit 1

For Even parity: Even number of 1’s, add a parity bit 0

So, number of 1’s becomes always even

13.4.2. Checksums –con’t

Example:

A sequence of bits 01101000 has odd number of 1’s.

The parity bit will be 1. So the sequence with the parity

bit will now be 011010001.

1. Sequence : 01101000-> odd no of 1’s

parity bit: 1 -> 011010001

A sequence of bits 11101110 will have an even parity as

it has even number of 1’s. So with the parity bit 0, the

sequence will be 111011100.

2. Sequence : 111011100->even no of 1’s

parity bit: 0 -> 111011100

13.4.2. Checksums –con’t

By finding one bit error in reading and writing the bits

and their parity bit results in sequence of bits that has

odd parity, so the error can be detected

Error detecting can be improved by keeping one bit for

each byte

Probability is 50% that any one parity bit will detect an

error, and chance that none of the eight do so is only one

in 2^8 or 1/256

Same way if n independent bits are used then the

probability is only 1/(2^n) of missing error

Any one-bit error in reading or writing the bits

results in a sequence of bits that has odd-parity.

The disk controller can count the number of 1’s

and can determine if the sector has odd parity in

the presence of an error.

13.4.3. Stable Storage

Checksums can detect the error but cannot correct it.

Sometimes we overwrite the previous contents of a

sector and yet cannot read the new contents correctly.

To deal with these problems, Stable Storage policy can

be implemented on the disks.

Sectors are paired and each pair represents one sectorcontents X.

The left copy of the sector may be represented as XL and

XR as the right copy.

13.4.3. Stable Storage Assumptions

We assume that copies are written with sufficient

number of parity bits to decrease the chance of bad

sector looks good when the parity checks are considered.

Also, If the read function returns a good value w for

either XL or XR then it is assumed that w is the true value

of X.

13.4.3. Stable Storage – Writing Policy

Write the value of X into XL. Check the value has status

“good”; i.e., the parity-check bits are correct in the

written copy. If not repeat write. If after a set number

of write attempts, we have not successfully written X in

XL, assume that there is a media failure in this sector. A

fix-up such as substituting a spare sector for XL must be

adopted.

Repeat (1) for XR.

13.4.3. Stable Storage – Reading Policy

The policy is to alternate trying to read XL and XR until a

good value is returned.

If a good value is not returned after pre chosen number

of tries, then it is assumed that X is truly unreadable.

13.4.4. Error Handling Capabilities of

Stable Storage

Failures: If out of Xl and Xr, one fails, it can be read form

other, but in case both fails X is not readable, and its

probability is very small

Write Failure: During power outage,

1. While writing Xl, the Xr, will remain good and X can

be read from Xr

2. After writing Xl, we can read X from Xl, as Xr may or

may not have the correct copy of X

13.4.5 Recovery from Disk Crashes

The most serious mode of failure for disks is “head

crash” where data permanently destroyed.

So to reduce the risk of data loss by disk crashes there

are number of schemes which are know as RAID

(Redundant Arrays of Independent Disks) schemes.

Each of the schemes starts with one or more disks that

hold the data and adding one or more disks that hold

information that is completely determined by the

contents of the data disks called Redundant Disk.

13.4.6. Mirroring as a Redundancy Technique

Mirroring Scheme is referred as RAID level 1 protection

against data loss scheme.

In this scheme we mirror each disk.

One of the disk is called as data disk and other

redundant disk.

In this case the only way data can be lost is if there is a

second disk crash while the first crash is being repaired.

13.4.7 Parity Blocks

RAID level 4 scheme uses only one redundant disk no

matter how many data disks there are.

In the redundant disk, the ith block consists of the parity

checks for the ith blocks of all the data disks.

It means, the jth bits of all the ith blocks of both data

disks and redundant disks, must have an even number

of 1’s and redundant disk bit is used to make this

condition true.

13.4.7 Parity Blocks – Reading disk

Reading data disk is same as reading block from

any disk.

• We could read block from each of the other disks and

compute the block of the disk we want to read by taking

the modulo-2 sum.

disk 2: 10101010

disk 3: 00111000

disk 4: 01100010

If we take the modulo-2 sum of the bits in each column,

we get

disk 1: 11110000

13.4.7 Parity Block - Writing

When we write a new block of a data disk, we need to

change that block of the redundant disk as well.

One approach to do this is to read all the disks and

compute the module-2 sum and write to the redundant

disk.

But this approach requires n-1 reads of data, write a

data block and write of redundant disk block.

Total = n+1 disk I/Os

Continue : Parity Block - Writing

•

Better approach will require only four disk I/Os

1. Read the old value of the data block being changed.

2. Read the corresponding block of the redundant disk.

3. Write the new data block.

4. Recalculate and write the block of the redundant disk.

Parity Blocks – Failure Recovery

If any of the data disk crashes then we just have to compute

the module-2 sum to recover the disk.

Suppose that disk 2 fails. We need to re compute each block of

the replacement disk. We are given the corresponding blocks of

the

first and third data disks and the redundant disk, so the

situation looks like:

disk 1: 11110000

disk 2: ????????

disk 3: 00111000

disk 4: 01100010

If we take the modulo-2 sum of each column, we deduce that

the missing block of disk 2 is : 10101010

13.4.8 An Improvement: RAID 5

RAID 4 is effective in preserving data unless there are two

simultaneous disk crashes.

Whatever scheme we use for updating the disks, we need

to read and write the redundant disk's block. If there are n

data disks, then the number of disk writes to the

redundant disk will be n times the average number of

writes to any one data disk.

However we do not have to treat one disk as the

redundant disk and the others as data disks. Rather, we

could treat each disk as the redundant disk for some of the

blocks. This improvement is often called RAID level 5.

Con’t: An Improvement: RAID 5

• For instance, if there are n + 1 disks numbered 0

through n, we could treat the ith cylinder of disk j as

redundant if j is the remainder when i is divided by n+1.

• For example, n = 3 so there are 4 disks. The first disk,

numbered 0, is redundant for its cylinders numbered 4,

8, 12, and so on, because these are the numbers that

leave remainder 0 when divided by 4.

• The disk numbered 1 is redundant for blocks numbered

1, 5, 9, and so on; disk 2 is redundant for blocks 2, 6.

10,. . ., and disk 3 is redundant for 3, 7, 11,. . . .

13.4.9 Coping With Multiple Disk

Crashes

•

Error-correcting codes theory known as Hamming code

leads to the RAID level 6.

•

By this strategy the two simultaneous crashes are

correctable.

The bits of disk 5 are the modulo-2 sum of the

corresponding bits of disks 1, 2, and 3.

The bits of disk 6 are the modulo-2 sum of the

corresponding bits of disks 1, 2, and 4.

The bits of disk 7 are the module2 sum of the

corresponding bits of disks 1, 3, and 4

Coping With Multiple Disk Crashes –

Reading/Writing

We may read data from any data disk normally.

To write a block of some data disk, we compute the

modulo-2 sum of the new and old versions of that block.

These bits are then added, in a modulo-2 sum, to the

corresponding blocks of all those redundant disks that

have 1 in a row in which the written disk also has 1.

13.5 Arranging data on disk

Data elements are represented as records, which stores

in consecutive bytes in same disk block.

Basic layout techniques of storing data :

1. Fixed-Length Records

2. Allocation criteria - data should start at word

boundary.

Fixed Length record header

1. A pointer to record schema.

2. The length of the record.

3. Timestamps to indicate last modified or last read.

Data on disk - Example

CREATE TABLE employee(

name CHAR(30) PRIMARY KEY,

address VARCHAR(255),

gender CHAR(1),

birthdate DATE );

Data should start at word boundary and contain header

and four fields name, address, gender and birthdate.

13.5 Packing Fixed-Length Records into

Blocks

Records are stored in the form of blocks on the disk and

they move into main memory when we need to update

or access them.

A block header is written first, and it is followed by series

of blocks.

13.5 Block header contains the following

information

Links to one or more blocks that are part of a network

of blocks.

Information about the role played by this block in such a

network.

Information about the relation, the tuples in this block

belong to.

A "directory" giving the offset of each record in the

block.

Time stamp(s) to indicate time of the block's last

modification and/or access.

13.5 Block header -Example

Along with the header we can pack as many record as we can

in one block as shown in the figure and remaining space will

be unused.

13.6 Representing Block And Record

Addresses

Address of a block and Record

In Main Memory

Address of the block is the virtual memory

address of the first byte

Address of the record within the block is the

virtual memory address of the first byte of the

record

In Secondary Memory: sequence of bytes describe

the location of the block in the overall system

Sequence of Bytes describe the location of the block :

the device Id for the disk, Cylinder number, etc.

13.6.1 Addresses In Client-server

Systems

The addresses in address space are represented in two

ways

Physical Addresses: byte strings that determine the

place within the secondary storage system where the

record can be found.

Logical Addresses: arbitrary string of bytes of some

fixed length

Physical Address bits are used to indicate:

Host to which the storage is attached

Identifier for the disk

Number of the cylinder

Number of the track

Offset of the beginning of the record

Addresses In Client-server Systems

(Contd..)

Map Table relates logical addresses to physical addresses.

Logical

Physical

Logical Address

Physical Address

13.6.2 Logical And Structured

Addresses

Purpose of logical address?

Gives more flexibility, when we

Move the record around within the block

Move the record to another block

Gives us an option of deciding what to do when a record is

deleted?

Unused

Rec

ord

4

Offset table

Header

Rec

ord

3

Rec

ord

2

Rec

ord

1

13.6.3 POINTER SWIZZLING

Having pointers is common in an object-relational

database systems

Important to learn about the management of pointers

Every data item (block, record, etc.) has two addresses:

database address: address on the disk

memory address, if the item is in virtual memory

Pointer Swizzling (Contd…)

Translation Table: Maps database address to memory

address

All addressable items in the database have entries in the

map table, while only those items currently in memory are

mentioned in the translation table

Database address

Dbaddr

Mem-addr

Memory Address

Pointer Swizzling (Contd…)

Pointer consists of the following two fields

Bit indicating the type of address

Database or memory address

Disk

Memory

Swizzled

Block 1

Block 1

Unswizzled

Block 2

Example 13.7

Block 1 has a record with pointers to a second record on

the same block and to a record on another block

If Block 1 is copied to the memory

The first pointer which points within Block 1 can be

swizzled so it points directly to the memory address of

the target record

Since Block 2 is not in memory, we cannot swizzle the

second pointer

Pointer Swizzling (Contd…)

Three types of swizzling

Automatic Swizzling

As soon as block is brought into memory, swizzle all

relevant pointers.

Swizzling on Demand

Only swizzle a pointer if and when it is actually

followed.

No Swizzling

Pointers are not swizzled they are accesses using the

database address.

Programmer Control Of Swizzling

Unswizzling

When a block is moved from memory back to disk, all

pointers must go back to database (disk) addresses

Use translation table again

Important to have an efficient data structure for the

translation table

Pinned Records And Blocks

A block in memory is said to be pinned if it cannot be

written back to disk safely.

If block B1 has swizzled pointer to an item in block B2,

then B2 is pinned

Unpin a block, we must unswizzle any pointers to it

Keep in the translation table the places in memory

holding swizzled pointers to that item

Unswizzle those pointers (use translation table to

replace the memory addresses with database (disk)

addresses

13.7.1 Records with Variable Fields

An effective way to represent variable length records

is as follows

Fixed length fields are Kept ahead of the variable

length fields

Record header contains

Length of the record

Pointers to the beginning of all variable

length fields except the first one.

Records with Variable Length Fields

header information

record length

to address

gender

birth date

name

address

Figure 2 : A Movie Star record with name and address

implemented as variable length character strings

13.7.2 Records with Repeating Fields

Records contains variable number of occurrences of a field F

All occurrences of field F are grouped together and the

record

Header contains a pointer to the first occurrence of field F

L bytes are devoted to one instance of field F

Locating an occurrence of field F within the record

Add to the offset for the field F which are the integer

multiples of L starting with 0 , L ,2L,3L and so on to locate

We stop upon reaching the offset of the field F.

13.7.2 Records with Repeating Fields

other header information

record length

to address

to movie pointers

name

address

pointers to movies

Figure 3 : A record with a repeating group of references to movies

13.7.2 Records with Repeating Fields

record header

information

address

to name

length of name

to address

length of address

to movie references

number of references

name

Figure 4 : Storing variable-length fields separately from the record

13.7.1 Records with Repeating Fields

Advantage

Keeping the record itself fixed length allows record to be

searched more efficiently, minimizes the overhead in the

block headers, and allows records to be moved within or

among the blocks with minimum effort.

Disadvantage

Storing variable length components on another block

increases the number of disk I/O’s needed to examine all

components of a record.

13.7.2 Records with Repeating Fields

A compromise strategy is to allocate a fixed portion of the

record for the repeating fields

If the number of repeating fields is lesser than

allocated space, then there will be some unused space

If the number of repeating fields is greater than

allocated space, then extra fields are stored in a

different location and

Pointer to that location and count of additional

occurrences is stored in the record

13.7.3 Variable Format Records

Records that do not have fixed schema

Variable format records are represented by sequence of

tagged fields

Each of the tagged fields consist of information

• Attribute or field name

• Type of the field

• Length of the field

• Value of the field

Why use tagged fields

• Information – Integration applications

• Records with a very flexible schema

13.7.3 Variable Format Records

code for name

code for string type

length

N

S

14

Clint Eastwood

code for restaurant owned

code for string type

length

R

S

16

Fig 5 : A record with tagged fields

Hog’s Breath Inn

13.7.4 Records that do not fit in a

block

When the length of a record is greater than block size ,then

then record is divided and placed into two or more blocks

Portion of the record in each block is referred to as a

RECORD FRAGMENT

Record with two or more fragments is called

SPANNED RECORD

Record that do not cross a block boundary is called

UNSPANNED RECORD

Spanned Records

Spanned records require the following extra header

information

• A bit indicates whether it is fragment or not

• A bit indicates whether it is first or last fragment of

a record

• Pointers to the next or previous fragment for the

same record

13.7.4 Records that do not fit in a

block

block header

record header

record 1

block 1

record

2-a

record

2-b

record 3

block 2

Figure 6 : Storing spanned records across blocks

13.7.5 BLOBS

Large binary objects are called BLOBS

e.g. : audio files, video files

Storage of BLOBS

Retrieval of BLOBS

13.8 Record Modification

What is Record ?

Record is a single, implicitly structured data item

in the database table. Record is also called as

Tuple.

What is definition of Record Modification ?

We say Records Modified when a data

manipulation operation is performed.

Modification Types:

Insertion, Deletion, Update

13.8 Insertion

Insertion of records without order

Records can be placed in a block with empty space or

in a new block.

Insertion of records in fixed order

Space available in the block

No space available in the block (outside the block)

Structured address

Pointer to a record from outside the block.

13.8 Insertion in fixed order

Space available within the block

Use of an offset table in the header of each block with

pointers to the location of each record in the block.

The records are slid within the block and the pointers in

the offset table are adjusted.

Offset

table

header

unused

Record 4

Record 3

Record 2

Record 1

13.8 Insertion in fixed order

No space available within the block (outside the block)

Find space on a “nearby” block.

•

•

In case of no space available on a block, look at the following block in sorted order of

blocks.

If space is available in that block ,move the highest records of first block 1 to block 2 and

slide the records around on both blocks.

Create an overflow block

•

•

•

Records can be stored in overflow block.

Each block has place for a pointer to an overflow block in its header.

The overflow block can point to a second overflow block as shown below.

Block

B

Overflow

block for B

13.8 Deletion

Recover space after deletion

When using an offset table, the records can be slid

around the block so there will be an unused region in

the center that can be recovered.

In case we cannot slide records, an available space

list can be maintained in the block header.

The list head goes in the block header and available

regions hold the links in the list.

13.8 Deletion

Use of tombstone

The tombstone is placed in a record in order to avoid

pointers to the deleted record to point to new records.

The tombstone is permanent until the entire database

is reconstructed.

If pointers go to fixed locations from which the location

of the record is found then we put the tombstone in

that fixed location. (See examples)

Where a tombstone is placed depends on the nature of

the record pointers.

Map table is used to translate logical record address to

physical address.

13.8 Deletion

Use of tombstone

If we need to replace records by tombstones, place the bit that serves

as the tombstone at the beginning of the record.

This bit remains the record location and subsequent bytes can be

reused for another record

Record 1

Record 2

Record 1 can be replaced, but the tombstone remains, record 2 has no

tombstone and can be seen when we follow a pointer to it.

82

13.8 Update

Fixed Length update

No effect on storage system as it occupies same

space as before update.

Variable length update

Longer length

Short length

83

13.8 Update

Variable length update (longer length)

Stored on the same block:

Sliding records

Creation of overflow block.

Stored on another block

Move records around that block

Create a new block for storing variable length fields.

Variable length update (Shorter length)

Same as deletion

Recover space

Consolidate space.

84

14.2 BTrees & Bitmap Indexes

14.2 BTree Structure

A balanced tree, meaning that all paths from the

leaf node have the same length.

There is a parameter n associated with each BTree

block. Each block will have space for n search keys

and n+1 pointers.

The root may have only 1 parameter, but all other

blocks most be at least half full.

14.2 Structure

● A typical node >

● a typical interior

node would have

pointers pointing to

leaves with out

values

● a typical leaf would

have pointers point

to records

N search keys

N+1 pointers

14.2 Application

The search key of the BTree is the primary key for the

data file.

Data file is sorted by its primary key.

Data file is sorted by an attribute that is not a key and

this attribute is the search key for the BTree.

14.2 Lookup

If at an interior node, choose the correct pointer to use.

This is done by comparing keys to search value.

If at a leaf node, choose the key that matches what you are looking

for and the pointer for that leads to the data.

14.2 Insertion

When inserting, choose the correct leaf node to put

pointer to data.

If node is full, create a new node and split keys

between the two.

Recursively move up, if cannot create new pointer to

new node because full, create new node.

This would end with creating a new root node, if

the current root was full.

14.2 Deletion

Perform lookup to find node to delete and delete it.

If node is no longer half full, perform join on adjacent

node and recursively delete up, or key move if that node

is full and recursively change pointer up.

14.2 Efficiency

Btrees allow lookup, insertion, and deletion of records

using very few disk I/Os.

Each level of a BTree would require one read. Then you

would follow the pointer of that to the next or final read.

Three levels are sufficient for Btrees. Having each block

have 255 pointers, 255^3 is about 16.6 million.

You can even reduce disk I/Os by keeping a level of a

BTree in main memory. Keeping the first block with 255

pointers would reduce the reads to 2, and even possible

to keep the next 255 pointers in memory to reduce

reads to 1.

14.7 BTree Indexes - Definition

A bitmap index for a field F is a collection of bit-vectors of

length n, one for each possible value that may appear in

that field F.[1]

14.7 What does that mean?

Assume relation R with

2 attributes A and B.

Attribute A is of type

Integer and B is of

type String.

6 records, numbered

1 through 6 as

shown.

A

B

1

30

foo

2

30

bar

3

40

baz

4

50

foo

5

40

bar

6

30

baz

14.7 Example Continued…

A bitmap for attribute B is:

Value

foo

bar

baz

Vector

100100

010010

001001

A

B

1

30

foo

2

30

bar

3

40

baz

4

50

foo

5

40

bar

6

30

baz

14.7 Where do we reach?

A bitmap index is a special kind of database index that

uses bitmaps.[2]

Bitmap indexes have traditionally been considered to

work well for data such as gender, which has a small

number of distinct values, e.g., male and female, but

many occurrences of those values.[2]

14.7 A little more…

A bitmap index for attribute A of relation R is:

A collection of bit-vectors

The number of bit-vectors = the number of distinct

values of A in R.

The length of each bit-vector = the cardinality of R.

The bit-vector for value v has 1 in position i, if the ith

record has v in attribute A, and it has 0 there if

not.[3]

Records are allocated permanent numbers.[3]

There is a mapping between record numbers and record

addresses.[3]

14.7 Motivation for Bitmap Indexes

Very efficient when used for partial match queries.[3]

They offer the advantage of buckets [2]

Where we find tuples with several specified attributes

without first retrieving all the record that matched in

each of the attributes.

They can also help answer range queries [3]

14.7 Another Example

Multidimensional Array of multiple types

{(5,d),(79,t),(4,d),(79,d),(5,t),(6,a)}

5

79

4

6

d

t

a

= 100010

= 010100

= 001000

= 000001

= 101100

= 010010

= 000001

14.7 Example Continued…

{(5,d),(79,t),(4,d),(79,d),(5,t),(6,a)}

Searching for items is easy, just AND together.

To search for (5,d)

5 = 100010

d = 101100

100010 AND 101100 = 100000

The location of the

record has been traced!

14.7 Compressed Bitmaps

Assume:

The number of records in R are n

Attribute A has m distinct values in R

The size of a bitmap index on attribute A is m*n.

If m is large, then the number of 1’s will be around 1/m.

Opportunity to encode

A common encoding approach is called run-length

encoding.[1]

Run-length encoding

Represents runs

A run is a sequence of i 0’s followed by a 1, by some suitable

binary encoding of the integer i.

A run of i 0’s followed by a 1 is encoded by:

First computing how many bits are needed to represent i, Say k

Then represent the run by k-1 1’s and a single 0 followed by k bits

which represent i in binary.

The encoding for i = 1 is 01. k = 1

The encoding for i = 0 is 00. k = 1

We concatenate the codes for each run together, and the sequence of bits is

the encoding of the entire bit-vector

Understanding with an Example

Let us decode the sequence 11101101001011

Staring at the beginning (left most bit):

First run: The first 0 is at position 4, so k = 4. The next 4 bits

are 1101, so we know that the first integer is i = 13

Second run: 001011

k=1

i=0

Last run: 1011

k=1

i=3

Our entire run length is thus 13,0,3, hence our bit-vector is:

0000000000000110001

Managing Bitmap Indexes

1) How do you find a specific bit-vector for a

value efficiently?

2) After selecting results that match, how do you retrieve

the results efficiently?

3) When data is changed, do you you alter bitmap index?

1) Finding bit vectors

Think of each bit-vector as a key to a value.[1]

Any secondary storage technique will be efficient in

retrieving the values.[1]

Create secondary key with the attribute value as a

search key [3]

Btree

Hash

2) Finding Records

Create secondary key with the record number as a

search key [3]

Or in other words,

Once you learn that you need record k, you can

create a secondary index using the kth position as a

search key.[1]

3) Handling Modifications

Two things to remember:

Record numbers must remain fixed once assigned

Changes to data file require changes to bitmap index

14.7 Deletion

Tombstone replaces deleted record

Corresponding bit is set to 0

14.7 Insertion

Record assigned the next record number.

A bit of value 0 or 1 is appended to each bit

vector

If new record contains a new value of the

attribute, add one bit-vector.

14.7 Modification

Change the bit corresponding to the old value

of the modified record to 0

Change the bit corresponding to the new value

of the modified record to 1

If the new value is a new value of A, then

insert a new bit-vector.

Chapter 15

15.1

Query Execution

111

15.1 What is a Query Processor

Group of components of a DBMS that converts a user

queries and data-modification commands into a

sequence of database operations

It also executes those operations

Must supply detail regarding how the query is to be

executed

112

15.1 Major parts of Query processor

Query Execution:

The algorithms that

manipulate the data of

the database.

Focus on the

operations of extended

relational algebra.

113

15.1Outline of Query Compilation

Query compilation

Parsing : A parse tree for the

query is constructed

Query Rewrite : The parse

tree is converted to an initial

query plan and transformed

into logical query plan (less

time)

Physical Plan Generation :

Logical Q Plan is converted into

physical query plan by selecting

algorithms and order of

execution of these operator.

114

15.1Physical-Query-Plan Operators

Physical operators are implementations of the operator

of relational algebra.

They can also be use in non relational algebra

operators like “scan” which scans tables, that is, bring

each tuple of some relation into main memory

115

15.1 Scanning Tables

One of the basic thing we can do in a Physical query plan is

to read the entire contents of a relation R.

Variation of this operator involves simple predicate, read

only those tuples of the relation R that satisfy the predicate.

Basic approaches to locate the tuples of a relation R

Table Scan

Relation R is stored in secondary memory with its

tuples arranged in blocks

It is possible to get the blocks one by one

Index-Scan

If there is an index on any attribute of Relation R, we

can use this index to get all the tuples of Relation R

116

15.1 Sorting While Scanning Tables

Number of reasons to sort a relation

Query could include an ORDER BY clause, requiring

that a relation be sorted.

Algorithms to implement relational algebra operations

requires one or both arguments to be sorted

relations.

Physical-query-plan operator sort-scan takes a

relation R, attributes on which the sort is to be made,

and produces R in that sorted order

117

15.1 Computation Model for Physical

Operator

Physical-Plan Operator should be selected wisely which is

essential for good Query Processor .

For “cost” of each operator is estimated by number of

disk I/O’s for an operation.

The total cost of operation depends on the size of the

answer, and includes the final write back cost to the total

cost of the query.

118

15.1 Parameters for Measuring Costs

Parameters that affect the performance of a query

Buffer space availability in the main memory at

the time of execution of the query

Size of input and the size of the output generated

The size of memory block on the disk and the size in

the main memory also affects the performance

B: The number of blocks are needed to hold all tuples of

relation R. Also denoted as B(R)

T: The number of tuples in relationR. Also denoted as T(R)

V: The number of distinct values that appear in a column of

a relation R.V(R, a)- is the number of distinct values of

column for a in relation R

119

15.1. I/O Cost for Scan Operators

If relation R is clustered, then the number of disk I/O for

the table-scan operator is = ~B disk I/O’s

If relation R is not clustered, then the number of required

disk I/O generally is much higher

A index on a relation R occupies many fewer than B(R)

blocks

That means a scan of the entire relation R which takes at

least B disk I/O’s will require more I/O’s than the entire

index

120

15.1. Iterators for Implementation of

Physical Operators

Many physical operators can be implemented as an

Iterator.

Three methods forming the iterator for an operation are:

1. Open( ) :

This method starts the process of getting tuples

It initializes any data structures needed to perform

the operation

121

15.1 Iterators for Implementation of

Physical Operators

2. GetNext( ):

Returns the next tuple in the result

If there are no more tuples to return, GetNext

returns a special value NotFound

3. Close( ) :

Ends the iteration after all tuples

It calls Close on any arguments of the operator

122

15.2 One-Pass Algorithms for Database

Operations -Introduction

The choice of an algorithm for each operator is an

essential part of the process of transforming a logical

query plan into a physical query plan.

Main classes of Algorithms:

Sorting-based methods

Hash-based methods

Index-based methods

Division based on degree difficulty and cost:

1-pass algorithms

2-pass algorithms

3 or more pass algorithms

123

15.2. One-Pass Algorithm Methods

Tuple-at-a-time, unary operations: (selection &

projection)

Full-relation, unary operations

Full-relation, binary operations (set & bag versions of

union)

124

15.2 One-Pass Algorithms for Tuple-at

-a-Time Operations

Tuple-at-a-time operations are selection and projection

read the blocks of R one at a time into an input buffer

perform the operation on each tuple

move the selected tuples or the projected tuples to

the output buffer

The disk I/O requirement for this process depends only

on how the argument relation R is provided.

If R is initially on disk, then the cost is whatever it

takes to perform a table-scan or index-scan of R.

125

15.2 A selection or projection being

performed on a relation R

126

15.2 One-Pass Algorithms for Unary,

fill-Relation Operations

Duplicate Elimination

To eliminate duplicates, we can read each block of R

one at a time, but for each tuple we need to make a

decision as to whether:

It is the first time we have seen this tuple, in which

case we copy it to the output, or

We have seen the tuple before, in which case we

must not output this tuple.

One memory buffer holds one block of R's tuples, and

the remaining M - 1 buffers can be used to hold a single

copy of every tuple.

127

15.2.Managing memory for a one-pass

duplicate-elimination

128

15.2. Duplicate Elimination

When a new tuple from R is considered, we compare it

with all tuples seen so far

if it is not equal: we copy both to the output and add

it to the in-memory list of tuples we have seen.

if there are n tuples in main memory: each new tuple

takes processor time proportional to n, so the

complete operation takes processor time proportional

to n2.

We need a main-memory structure that allows each of

the operations:

Add a new tuple, and

Tell whether a given tuple is already there

129

15.2. Duplicate Elimination (contd.)

The different structures that can be used for such main

memory structures are:

Hash table

Balanced binary search tree

130

15.2 One-Pass Algorithms for Unary,

fill-Relation Operations

Grouping

The grouping operation gives us zero or more

grouping attributes and presumably one or more

aggregated attributes

If we create in main memory one entry for each

group then we can scan the tuples of R, one block at

a time.

The entry for a group consists of values for the

grouping attributes and an accumulated value or

values for each aggregation.

131

15.2. Grouping

The accumulated value is:

For MIN(a) or MAX(a) aggregate, record minimum

/maximum value, respectively.

For any COUNT aggregation, add 1 for each tuple of

group.

For SUM(a), add value of attribute a to the

accumulated sum for its group.

AVG(a) is a hard case. We must maintain 2

accumulations: count of no. of tuples in the group &

sum of a-values of these tuples. Each is computed as

we would for a COUNT & SUM aggregation,

respectively. After all tuples of R are seen, take

quotient of sum & count to obtain average.

132

15.2. One-Pass Algorithms for Binary

Operations

Binary operations include:

Union

Intersection

Difference

Product

Join

133

15.2. Set Union

We read S into M - 1 buffers of main memory and build

a search structure where the search key is the entire

tuple.

All these tuples are also copied to the output.

Read each block of R into the Mth buffer, one at a time.

For each tuple t of R, see if t is in S, and if not, we

copy t to the output. If t is also in S, we skip t.

134

15.2. Set Intersection

Read S into M - 1 buffers and build a search structure

with full tuples as the search key.

Read each block of R, and for each tuple t of R, see if t

is also in S. If so, copy t to the output, and if not,

ignore t.

135

15.2. Set Difference

Read S into M - 1 buffers and build a search structure

with full tuples as the search key.

To compute R -s S, read each block of R and examine

each tuple t on that block. If t is in S, then ignore t; if

it is not in S then copy t to the output.

To compute S -s R, read the blocks of R and examine

each tuple t in turn. If t is in S, then delete t from the

copy of S in main memory, while if t is not in S do

nothing.

After considering each tuple of R, copy to the output

those tuples of S that remain.

136

15.2. Bag Intersection

Read S into M - 1 buffers.

Multiple copies of a tuple t are not stored individually.

Rather store 1 copy of t & associate with it a count

equal to no. of times t occurs.

Next, read each block of R, & for each tuple t of R see

whether t occurs in S. If not ignore t; it cannot appear

in the intersection. If t appears in S, & count

associated with t is (+)ve, then output t & decrement

count by 1. If t appears in S, but count has reached 0,

then do not output t; we have already produced as

many copies of t in output as there were copies in S.

137

15.2. Bag Difference

To compute S -B R, read tuples of S into main memory

& count no. of occurrences of each distinct tuple.

Then read R; check each tuple t to see whether t

occurs in S, and if so, decrement its associated count.

At the end, copy to output each tuple in main memory

whose count is positive, & no. of times we copy it

equals that count.

To compute R -B S, read tuples of S into main memory

& count no. of occurrences of distinct tuples.

138

15.2. Bag Difference (…contd.)

Think of a tuple t with a count of c as c reasons not to

copy t to the output as we read tuples of R.

Read a tuple t of R; check if t occurs in S. If not, then

copy t to the output. If t does occur in S, then we look at

current count c associated with t. If c = 0, then copy t to

output. If c > 0, do not copy t to output, but decrement

c by 1.

139

15.2. Product

Read S into M - 1 buffers of main memory

Then read each block of R, and for each tuple t of R

concatenate t with each tuple of S in main memory.

Output each concatenated tuple as it is formed.

This algorithm may take a considerable amount of

processor time per tuple of R, because each such tuple

must be matched with M - 1 blocks full of tuples.

However, output size is also large, & time/output tuple is

small.

140

15.2. Natural Join

Convention: R(X, Y) is being joined with S(Y, Z), where Y

represents all the attributes that R and S have in

common, X is all attributes of R that are not in the

schema of S, & Z is all attributes of S that are not in the

schema of R. Assume that S is the smaller relation.

To compute the natural join, do the following:

Read all tuples of S & form them into a mainmemory search structure.

Hash table or balanced tree are good e.g. of

such structures. Use M - 1 blocks of memory for this

purpose.

141

15.2. Natural Join (…contd.)

Read each block of R into 1 remaining main-memory

buffer.

For each tuple t of R, find tuples of S that agree with t

on all attributes of Y, using the search structure.

For each matching tuple of S, form a tuple by joining it

with t, & move resulting tuple to output.

142

15.5 Two Pass algorithms based on

Hashing

Hashing is done if the data is too big to store in main

memory buffers.

Hash all the tuples of the argument(s) using an

appropriate hash key.

For all the common operations, there is a way to

select the hash key so all the tuples that need to be

considered together when we perform the operation

have the same hash value.

This reduces the size of the operand(s) by a factor

equal to the number of buckets.

15.5 Partitioning Relations by Hashing

Algorithm:

initialize M-1 buckets using M-1 empty buffers;

FOR each block b of relation R DO BEGIN

read block b into the Mth buffer;

FOR each tuple t in b DO BEGIN

IF the buffer for bucket h(t) has no room for t THEN

BEGIN

copy the buffer t o disk;

initialize a new empty block in that buffer;

END;

copy t to the buffer for bucket h(t);

END ;

END ;

FOR each bucket DO

IF the buffer for this bucket is not empty THEN

write the buffer to disk;

15.5 Duplicate Elimination

For the operation δ(R) hash R to M-1 Buckets.

(Note that two copies of the same tuple t will hash to the

same bucket)

Do duplicate elimination on each bucket Ri

independently, using one-pass algorithm

The result is the union of δ(Ri), where Ri is the portion of

R that hashes to the ith bucket

15.5 Requirements

Number of disk I/O's: 3*B(R)

B(R) < M(M-1), only then the two-pass, hash-based

algorithm will work

In order for this to work, we need:

hash function h evenly distributes the tuples among

the buckets

each bucket Ri fits in main memory (to allow the onepass algorithm)

i.e., B(R) ≤ M2

15.5 Grouping and Aggregation

Hash all the tuples of relation R to M-1 buckets, using a

hash function that depends only on the grouping

attributes

(Note: all tuples in the same group end up in the same

bucket)

Use the one-pass algorithm to process each bucket

independently

Uses 3*B(R) disk I/O's, requires B(R) ≤ M2

15.5 Union, Intersection, and

Difference

For binary operation we use the same hash function to

hash tuples of both arguments.

R U S we hash both R and S to M-1

R ∩ S we hash both R and S to 2(M-1)

R-S we hash both R and S to 2(M-1)

Requires 3(B(R)+B(S)) disk I/O’s.

Two pass hash based algorithm requires min(B(R)+B(S))≤

M2

15.5 Hash-Join Algorithm

Use same hash function for both relations; hash function

should depend only on the join attributes

Hash R to M-1 buckets R1, R2, …, RM-1

Hash S to M-1 buckets S1, S2, …, SM-1

Do one-pass join of Ri and Si, for all I

3*(B(R) + B(S)) disk I/O's; min(B(R),B(S)) ≤ M2

15.5 Sort based Vs Hash based

For binary operations, hash-based only limits size to min

of arguments, not sum

Sort-based can produce output in sorted order, which can

be helpful

Hash-based depends on buckets being of equal size

Sort-based algorithms can experience reduced rotational

latency or seek time

15.6 Index-Based Algorithms Clustering and Non clustering Indexes

Clustered Relation: Tuples are packed into roughly as

few blocks as can possibly hold those tuples

Clustering indexes: Indexes on attributes that all the

tuples with a fixed value for the search key of this index

appear on roughly as few blocks as can hold them

A relation that isn’t clustered cannot have a clustering

index

A clustered relation can have nonclustering indexes

15.6 Index-Based Selection

For a selection σC(R), suppose C is of the form a=v,

where a is an attribute

For clustering index R.a:

the number of disk I/O’s will be B(R)/V(R,a)

The actual number may be higher:

1. index is not kept entirely in main memory

2. they spread over more blocks

3. may not be packed as tightly as possible into blocks

152

15.6 Example

B(R)=1000, T(R)=20,000 number of I/O’s required:

1. clustered, not index

1000

2. not clustered, not index

20,000

3. If V(R,a)=100, index is clustering

10

4. If V(R,a)=10, index is nonclustering 2,000

153

15.6 Joining by Using an Index

Natural join R(X, Y) S S(Y, Z)

Number of I/O’s to get R

Clustered: B(R)

Not clustered: T(R)

Number of I/O’s to get tuple t of S

Clustered: T(R)B(S)/V(S,Y)

Not clustered: T(R)T(S)/V(S,Y)

154

15.6 Example

R(X,Y): 1000 blocks S(Y,Z)=500 blocks

Assume 10 tuples in each block,

so T(R)=10,000 and T(S)=5000

V(S,Y)=100

If R is clustered, and there is a clustering index on Y for S

the number of I/O’s for R is:

1000

the number of I/O’s for S is10,000*500/100=50,000

155

15.6 Joins Using a Sorted Index

Natural join R(X, Y) S (Y, Z) with index on Y for either

R or S

Extreme case: Zig-zag join

Example:

relation R(X,Y) and R(Y,Z) with index on Y for both

relations

search keys (Y-value) for R: 1,3,4,4,5,6

search keys (Y-value) for S: 2,2,4,6,7,8

156

15.7 Buffer Management -What does a

buffer manager do?

Assume there are M of main-memory buffers needed for the operators

on relations to store needed data.

In practice:

1) rarely allocated in advance

2) the value of M may vary depending on system conditions

Therefore, buffer manager is used to allow processes to get the

memory they need, while minimizing the delay and unclassifiable

requests.

15.7. The role of the buffer manager

Read/Writes

Requests

Buffers

Buffer

manager

Figure 1: The role of the buffer manager : responds to requests for

main-memory access to disk blocks

15.7.1 Buffer Management Architecture

Two broad architectures for a buffer manager:

1) The buffer manager controls main memory directly.

• Relational DBMS

2) The buffer manager allocates buffers in virtual memory,

allowing the OS to decide how to use buffers.

• “main-memory” DBMS

• “object-oriented” DBMS

15.7.1 Buffer Pool

Key setting for the Buffer manager to be efficient:

The buffer manager should limit the number of buffers in

use so that they fit in the available main memory, i.e. Don’t

exceed available space.

The number of buffers is a parameter set when the DBMS is

initialized.

No matter which architecture of buffering is used, we simply

assume that there is a fixed-size buffer pool, a set of

buffers available to queries and other database actions.

15.7.1 Buffer Pool

Page Requests from Higher Levels

BUFFER POOL

disk page

free frame

MAIN MEMORY

DISK

DB

choice of frame dictated

by replacement policy

Data must be in RAM for DBMS to operate on it!

Buffer Manager hides the fact that not all data is in RAM.

15.7.2 Buffer Management Strategies

Buffer-replacement strategies:

When a buffer is needed for a newly requested block and the

buffer pool is full, what block to throw out the buffer

pool?

15.7.2 Buffer-replacement strategy LRU

Least-Recently Used (LRU):

To throw out the block that has not been read or written

for the longest time.

• Requires more maintenance but it is effective.

• Update the time table for every access.

• Least-Recently Used blocks are usually less likely to be

accessed sooner than other blocks.

15.7.2 Buffer-replacement strategy -FIFO

First-In-First-Out (FIFO):

The buffer that has been occupied the longest by the

same block is emptied and used for the new block.

• Requires less maintenance but it can make more

mistakes.

• Keep only the loading time

• The oldest block doesn’t mean it is less likely to be

accessed.

Example: the root block of a B-tree index

15.7.2.Buffer-replacement strategy –

“Clock”

The “Clock” Algorithm (“Second Chance”)

Think of the 8 buffers as arranged in a circle, shown

as Figure 3

Flag 0 and 1:

buffers with a 0 flag are ok to sent their

contents back to disk, i.e. ok to be replaced

buffers with a 1 flag are not ok to be replaced

15.7.2 Buffer-replacement strategy –

“Clock”

0

0

1

0

the buffer with

a 0 flag will

be replaced

0

0

1

1

Start point to

search a 0 flag

The flag will

be set to 0

By next time the hand

reaches it, if the content of

this buffer is not accessed,

i.e. flag=0, this buffer will

be replaced.

That’s “Second Chance”.

Figure 3: the clock algorithm

15.7.2 Buffer-replacement strategy -Clock

a buffer’s flag set to 1 when:

a block is read into a buffer

the contents of the buffer is accessed

a buffer’s flag set to 0 when:

the buffer manager needs a buffer for a new block, it looks

for the first 0 it can find, rotating clockwise. If it passes 1’s,

it sets them to 0.

15.7 System Control helps Bufferreplacement strategy

System Control

The query processor or other components of a DBMS can give

advice to the buffer manager in order to avoid some of the

mistakes that would occur with a strict policy such as

LRU,FIFO or Clock.

For example:

A “pinned” block means it can’t be moved to disk without first

modifying certain other blocks that point to it.

In FIFO, use “pinned” to force root of a B-tree to remain in

memory at all times.

15.7.3 The Relationship Between Physical

Operator Selection and Buffer Management

Problem:

Physical Operator expected certain number of buffers M

for execution.

However, the buffer manager may not be able to

guarantee these M buffers are available.

15.7.3 The Relationship Between Physical

Operator Selection and Buffer Management

Questions:

Can the algorithm adapt to changes of M, the number of

main-memory buffers available?

When available buffers are less than M, and some blocks

have to be put in disk instead of in memory.

How the buffer-replacement strategy impact the performance

(i.e. the number of additional I/O’s)?

15.7 Example

FOR each chunk of M-1 blocks of S DO BEGIN

read these blocks into main-memory buffers;

organize their tuples into a search structure whose

search key is the common attributes of R and S;

FOR each block b of R DO BEGIN

read b into main memory;

FOR each tuple t of b DO BEGIN

find the tuples of S in main memory that

join with t ;

output the join of t with each of these tuples;

END ;

END ;

END ;

Figure 15.8: The nested-loop join algorithm

15.7 Example

The outer loop number (M-1) depends on the average

number of buffers are available at each iteration.

The outer loop use M-1 buffers and 1 is reserved for a block

of R, the relation of the inner loop.

If we pin the M-1 blocks we use for S on one iteration of

the outer loop, we shall not lose their buffers during the

round.

Also, more buffers may become available and then we could

keep more than one block of R in memory.

Will these extra buffers improve the running time?

15.7 Example

CASE1: NO

Buffer-replacement strategy: LRU

Buffers for R: k

We read each block of R in order into buffers.

By end of the iteration of the outer loop, the last k blocks of

R are in buffers.

However, next iteration will start from the beginning of R

again.

Therefore, the k buffers for R will need to be replaced.

15.7 Example

CASE 2: YES

Buffer-replacement strategy: LRU

Buffers for R: k

We read the blocks of R in an order that alternates:

firstlast and then lastfirst.

In this way, we save k disk I/Os on each iteration of

the outer loop except the first iteration.

15.7 Other Algorithms and M buffers

Other Algorithms also are impact by M and the bufferreplacement strategy.

Sort-based algorithm

If M shrinks, we can change the size of a sublist.

Unexpected result: too many sublists to allocate each

sublist a buffer.

Hash-based algorithm

If M shrinks, we can reduce the number of buckets, as long

as the buckets still can fit in M buffers.

15.8 Algorithms using more than two

passes

Reason that we use more than two passes:

Two passes are usually enough, however, for the largest

relation, we use as many passes as necessary.

Multi-pass Sort-based Algorithms

Suppose we have M main-memory buffers available to

sort a relation R, which we assume is stored clustered.

Then we do the following:

15.8 Algorithms using more than two

passes

BASIS:

If R fits in M blocks (i.e., B(R)<=M)

1. Read R into main memory.

2. Sort it using any main-memory sorting algorithm.

3. Write the sorted relation to disk.

INDUCTION:

If R does not fit into main memory.

1. Partition the blocks holding R into M groups, which

we shall call R1, R2, R3…

2. Recursively sort Ri for each i=1,2,3…M.

3. Merge the M sorted sublists.

15.8 Algorithms using more than two

passes

If we are not merely sorting R, but performing a unary

operation such as δ or γ on R.

We can modify the above so that at the final merge we

perform the operation on the tuples at the front of the

sorted sublists.

That is:

For a δ, output one copy of each distinct tuple, and skip

over copies of the tuple.

For a γ, sort on the grouping attributes only, and

combine the tuples with a given value of these grouping

attributes.

15.8 Algorithms using more than two

passes

Conclusion

The two pass algorithms based on sorting or hashing

have natural recursive analogs that take three or more

passes and will work for larger amounts of data.

The Query Compiler

16.1 Parsing and Preprocessing

16.1 Parsing and Preprocessing–Query

compilation is divided into three steps

Parsing: Parse SQL query into parser tree.

2. Logical query plan: Transforms parse tree into

expression tree of relational algebra.

3.Physical query plan: Transforms logical query

plan into physical query plan.

. Operation performed

. Order of operation

. Algorithm used

. The way in which stored data is obtained and

passed from one

operation to another.

16.1.1 Syntax Analysis and Parse Tree

Parser takes the sql query and convert it to parse

tree. Nodes of parse tree:

1. Atoms: known as Lexical elements such as key

words, constants, parentheses, operators, and

other schema elements.

2. Syntactic categories: Subparts that plays a

similar role in a query as <Query> , <Condition>

16.1.2.Grammar for Simple Subset of SQL

<Query> ::= <SFW>

<Query> ::= (<Query>)

<SFW> ::= SELECT <SelList> FROM <FromList> WHERE <Condition>

<SelList> ::= <Attribute>,<SelList>

<SelList> ::= <Attribute>

<FromList> ::= <Relation>, <FromList>

<FromList> ::= <Relation>

<Condition>

<Condition>

<Condition>

<Condition>

<Tuple> ::=

::= <Condition> AND <Condition>

::= <Tuple> IN <Query>

::= <Attribute> = <Attribute>

::= <Attribute> LIKE <Pattern>

<Attribute>

Atoms(constants), <syntactic categories>(variable),

::= (can be expressed/defined as)

16.1 Query and Parse Tree

StarsIn(title,year,starName)

MovieStar(name,address,gender,birthdate)

Query:

Give titles of movies that have at least one star born in

1960

SELECT title FROM StarsIn WHERE starName IN

(

SELECT name FROM MovieStar WHERE

birthdate LIKE '%1960%'

);

16.1 Query and Parse Tree

16.1.3. The Preprocessor

Functions of Preprocessor

. If a relation used in the query is virtual view then each use

of this relation in the form-list must replace by parser tree

that describe the view.

. It is also responsible for semantic checking

1. Checks relation uses : Every relation mentioned in FROMclause must be a relation or a view in current schema.

2. Check and resolve attribute uses: Every attribute

mentioned in SELECT or WHERE clause must be an attribute

of same relation in the current scope.

3. Check types: All attributes must be of a type appropriate

to their uses.

16.1.3. The Preprocessor

StarsIn(title,year,starName)

MovieStar(name,address,gender,birthdate)

Query:

Give titles of movies that have at least one star born in

1960

SELECT title FROM StarsIn WHERE starName IN

(

SELECT name FROM MovieStar WHERE

birthdate LIKE '%1960%'

);

16.1.4. Preprocessing Queries Involving

Views

When an operand in a query is a virtual view, the

preprocessor needs to replace the operand by a piece of

parse tree that represents how the view is constructed

from base table.

Base Table: Movies( title, year, length, genre, studioname,

producerC#)

View definition : CREATE VIEW ParamountMovies AS

SELECT title, year FROM movies

WHERE studioName = 'Paramount';

Example based on view:

SELECT title FROM ParamountMovies WHERE year = 1979;

16.2

Algebraic Laws For Improving

Query Plans

16.2 Optimizing the Logical Query Plan

The translation rules converting a parse tree to a logical

query tree do not always produce the best logical query

tree.

It is often possible to optimize the logical query tree by

applying relational algebra laws to convert the original

tree into a more efficient logical query tree.

Optimizing a logical query tree using relational algebra

laws is called heuristic optimization

16.2 Relational Algebra Laws

These laws often involve the properties of:

commutativity - operator can be applied to operands

independent of order.

E.g. A + B = B + A - The “+” operator is commutative.

associativity - operator is independent of operand

grouping.

E.g. A + (B + C) = (A + B) + C - The “+” operator is

associative.

16.2 Associative and Commutative

Operators

The relational algebra operators of cross-product (×), join

(⋈), union, and intersection are all associative and

commutative.

Commutative

Associative

R X S=S X R

(R X S) X T = S X (R X T)

R⋈S=S⋈R

(R ⋈ S) ⋈ T= S ⋈ (R ⋈ T)

RS=SR

(R S) T = S (R T)

R ∩S =S∩ R

(R ∩ S) ∩ T = S ∩ (R ∩ T)

16.2 Laws Involving Selection

Complex selections involving AND or OR can be broken

into two or more selections: (splitting laws)

σC1 AND C2 (R) = σC1( σC2 (R))

σC1 OR C2 (R) = ( σC1 (R) ) S ( σC2 (R) )

Example

R={a,a,b,b,b,c}

p1 satisfied by a,b, p2 satisfied by b,c

σp1vp2 (R) = {a,a,b,b,b,c}

σp1(R) = {a,a,b,b,b}

σp2(R) = {b,b,b,c}

σp1 (R) U σp2 (R) = {a,a,b,b,b,c}

16.2. Laws Involving Selection (Contd..)

Selection is pushed through both arguments for union:

σC(R S) = σC(R) σC(S)

Selection is pushed to the first argument and optionally

the second for difference:

σC(R - S) = σC(R) - S

σC(R - S) = σC(R) - σC(S)

All other operators require selection to be pushed to only

one of the arguments.

For joins, may not be able to push selection to both if

argument does not have attributes selection requires.

σC(R × S) = σC(R) × S

σC(R ∩ S) = σC(R) ∩ S

σC(R ⋈ S) = σC(R) ⋈ S

σC(R ⋈D S) = σC(R) ⋈D S

16.2. Laws Involving Selection (Contd..)

Example

Consider relations R(a,b) and S(b,c) and the expression

σ (a=1 OR a=3) AND b<c (R ⋈S)

σ a=1 OR a=3(σ b<c (R ⋈S))

σ a=1 OR a=3(R ⋈ σ b<c (S))

σ a=1 OR a=3(R) ⋈ σ b<c (S)

16.2. Laws Involving Projection

Like selections, it is also possible to push projections down

the logical query tree. However, the performance gained is

less than selections because projections just reduce the

number of attributes instead of reducing the number of

tuples.

Laws for pushing projections with joins:

πL(R × S) = πL(πM(R) × πN(S))

πL(R ⋈ S) = πL((πM(R) ⋈ πN(S))

πL(R ⋈D S) = πL((πM(R) ⋈D πN(S))

Laws for pushing projections with set operations.

16.2. Laws Involving Projection

Projection can be performed entirely before union.

πL(R UB S) = πL(R) UB πL(S)

Projection can be pushed below selection as long as we

also keep all attributes needed for the selection (M = L

attr(C)).

πL ( σC (R)) = πL( σC (πM(R)))

16.2. Laws Involving Join

We have previously seen these important rules about

joins:

Joins are commutative and associative.

Selection can be distributed into joins.

Projection can be distributed into joins.

16.2. Laws Involving Duplicate

Elimination

The duplicate elimination operator (δ) can be pushed

through many operators.

R has two copies of tuples t, S has one copy of t,

δ (RUS)=one copy of t

δ (R) U δ (S)=two copies of t

Laws for pushing duplicate elimination operator (δ):

δ(R × S) = δ(R) × δ(S)

δ(R

S) = δ(R)

δ(S)

δ(R D S) = δ(R)

D δ(S)

δ( σC(R) = σC(δ(R))

The duplicate elimination operator (δ) can also be pushed

through bag intersection, but not across union,

difference, or projection in general.