HOBBES Y ROUSSEAU

advertisement

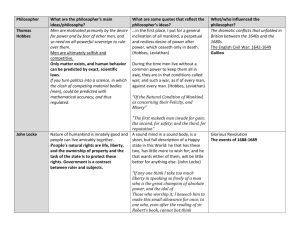

HOBBES In Leviathan, Hobbes set out his doctrine of the foundation of states and legitimate governments. Leviathan was written during the English Civil War; much of the book is occupied with demonstrating the necessity of a strong central authority to avoid the evil of discord and civil war. Hobbes postulates what life would be like without government, a condition which he calls the state of nature. In that state, each person would have a right, or license, to everything in the world. This, Hobbes argues, would lead to a "war of all against all" (bellum omnium contra omnes). The description contains what has been called one of the best known passages in English philosophy, which describes the natural state mankind would be in, were it not for political community: In such condition, there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. Hobbes, Leviathan. In such a state, people fear death, and lack both the things necessary to commodius living, and the hope of being able to toil to obtain them. So in order to avoid it people accede to establish a civil society. According to Hobbes, society is a population beneath a sovereign authority, to whom all individuals in that society cede some rights for the sake of protection. Any abuses of power by this authority can not be resisted because the sovereign power of the protector comes because of people surrendering their own sovereign power for protection and thereby they are the authors of all decisions made by the sovereign. There is no doctrine of separation of powers in Hobbes's discussion. ROUSSEAU “The first man who, having fenced in a piece of land, said "This is mine," and found people naïve enough to believe him, that man was the true founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes and crying to his fellows: beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody”. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality In common with other philosophers of the day, Rousseau looked to a hypothetical state of nature as a normative guide. Rousseau criticizes Hobbes for asserting that since man in the "state of nature has no idea of goodness, he must be naturally wicked; that he is vicious because he does not know virtue". On the contrary, Rousseau holds that "uncorrupted morals" prevail in the "state of nature". Rousseau asserted that the stage of human development associated with what he called "savages" was the best or optimal in human development: "Nothing is so gentle as man in his primitive state, when placed by nature at an equal distance from the stupidity of brutes and the fatal enlightenment of civil man.”. Referring to the stage of human development which Rousseau associates with savages, Rousseau writes: "This period of the development of human faculties must have been the happiest and most durable epoch. The more one reflects on it, the more one finds that this state was the least subject to upheavals and the best for man, and that he must have left it only by virtue of some fatal chance happening that, for the common good, ought never to have happened. The example of savages, almost all of whom have been found in this state, seems to confirm that the human race had been made to remain in it always; that this state is the veritable youth of the world; and that all the subsequent progress has been in appearance so many steps toward the perfection of the individual, and in fact toward the decay of the species.” The earliest solitary humans possessed a basic drive for self-preservation and a natural disposition to compassion or pity. As they began to live in groups and form clans they also began to experience family love, which Rousseau saw as the source of the greatest happiness known to humanity. As long as differences in wealth and status among families were minimal, the first coming together in groups was accompanied by a fleeting golden age of human flourishing. The development of agriculture, metallurgy, private property, and the division of labour and resulting dependency on one another, however, led to economic inequality and conflict. As population pressures forced them to associate more and more closely, they underwent a psychological transformation: They began to see themselves through the eyes of others and came to value the good opinion of others as essential to their self-esteem. Rousseau explains how the desire to have value in the eyes of others comes to undermine personal integrity and authenticity in a society marked by interdependence, and hierarchy. In the last chapter of the Social Contract, Rousseau would ask "What is to be done?" He answers that now all men can do is to cultivate virtue in themselves and submit to their lawful rulers. To his readers, however, the inescapable conclusion was that a new and more equitable Social Contract was needed. The Social Contract, arguably Rousseau's most important work, outlines the basis for a legitimate political order becoming one of the most influential works of political philosophy in the Western tradition. The treatise begins with the dramatic opening lines, "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. Those who think themselves the masters of others are indeed greater slaves than they." Rousseau claimed that the state of nature was a primitive condition without law or morality, which human beings left for the benefits and necessity of cooperation. As society developed, division of labor and private property required the human race to adopt institutions of law. In the degenerate phase of society, man is prone to be in frequent competition with his fellow men while also becoming increasingly dependent on them. This double pressure threatens both his survival and his freedom. According to Rousseau, by joining together into civil society through the social contract and abandoning their claims of natural right, individuals can both preserve themselves and remain free. This is because submission to the authority of the general will of the people as a whole guarantees individuals against being subordinated to the wills of others and also ensures that they obey themselves because they are, collectively, the authors of the law. The government is composed of magistrates, charged with implementing and enforcing the general will. The "sovereign" is the rule of law, ideally decided on by direct democracy in an assembly.