1. La Asignatura - Universidad de Granada

advertisement

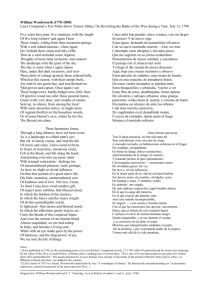

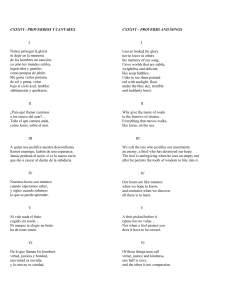

[Escribir texto] [Escribir texto] [Escribir texto] Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Filologías Inglesa y Alemana Literatura Inglesa III Guía Didáctica Curso 2012-2013 Prof. Dr. Miriam Fernández Santiago Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III 1 Prof. Miriam Fernández Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández 0.- Presentación de la Guía: Esta Guía contiene información acerca de los contenidos, objetivos, actividades, metodología, criterios de evaluación y otros asuntos de interés relativos al Curso “Literatura Inglesa III” que se imparte dentro de la titulación de Grado en Estudios Ingleses de la Universidad de Granada. Examínala atentamente pues en ella se basa todo el trabajo del curso. Si tienes dificultades para interpretar alguna cuestión o deseas información complementaria, no dudes en solicitarla a la profesora a cargo de tu grupo de la asignatura. 1. La Asignatura: 0.1. Datos de la Asignatura: Subject: “Literatura Inglesa III”. Type: Compulsory Total Credit N. (ECTS): 6 Term: 5 0.2. Número de Horas de Trabajo del Profesional en Formación: Actividad Theory Sessions Practice Sessions Office hours Individual (Home) Work Exams Total Hours 16 32 4,5 96 Presencial/No Presencial P P P/NP NP 6 150 P Prerrequisitos y/o recomendaciones: Se recomienda haber cursado satisfactoriamente la asignatura “Técnicas de estudio de la literatura en lengua inglesa”, “Literatura Inglesa I” y “Literatura Inglesa II”. - Nivel de inglés en sus cuatro destrezas correspondiente al establecido para el curso en el que se desarrolla la asignatura (C1). - Dominio de la capacidad de analizar textos críticamente y de redactar ensayos utilizando la terminología adecuada, haciendo un uso apropiado de las prácticas argumentativas y expositivas adquiridas. 0.1. La Profesora Miriam Fernández Santiago (Office to be determined) Prof. Contratado Doctor Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Office hours: Mon-Tues-Wed 17:00-18:00. Tel.: 958 24 Email: mirfer@ugr.es Research Interests: Literary Studies in English Cultural Studies Critical Theory 2 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández Objetivos y Competencias: 2.1. Objetivos: 2.1.1. Cognoscitivos OBJETIVOS GENERALES. 1. Conocer las disciplinas de estudio de la literatura en lengua inglesa y sus distintos géneros, así como desarrollar la capacidad de comentario y análisis mediante la aplicación de diferentes perspectivas de la crítica literaria. 2. Involucrarse activamente en el aprendizaje dentro de un clima de participación, mediación, cooperación y comunicación interpersonal, responsabilizándose de la construcción del propio saber, durante la formación del Grado, y asumir la importancia de este proceso a lo largo de la vida. 3. Desarrollar la autonomía en el aprendizaje mediante metas factibles y útiles, la búsqueda de recursos y bibliografía, así como la lectura analítica e inquisitiva de estos materiales. 4. Adquirir la capacidad de trabajo efectivo en equipo, de organización de trabajos, y de análisis y resolución de problemas. OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS: 1. Conocer de forma panorámica el contexto histórico del Reino Unido como telón de fondo para el estudio de las manifestaciones literarias de cada período histórico. 2. Conocer los principales movimientos, géneros, autores y obras de los períodos históricos comprendidos en el temario. 3. Aplicar las herramientas apropiadas para analizar y comentar los aspectos literarios, formales e ideológicos de los textos estudiados. 4. Desarrollar apropiadamente las destrezas necesarias para la articulación razonada de las lecturas realizadas por medio de la elaboración de ensayos críticos y discusiones en clase. 2.2. Competencias 2.2.1. Competencias COMPETENCIAS ESPECÍFICAS 1) Cognitivas-saber: Conocimiento histórico y filológico de las etapas, movimientos, autores y obras de la literatura inglesa del siglo XIX. 2) Procedimentales/instrumentales-saber hacer: 1. Lectura crítica y detallada (close reading) de textos literarios en lengua inglesa. 2. Aplicación de las técnicas de análisis de la literatura en sus tres géneros literarios principales (narrativa, poesía y teatro) a través de comentarios de texto. 3. Aplicación de diversas corrientes críticas al estudio y análisis de textos literarios en lengua inglesa. 4. Redacción de ensayos sobre textos literarios utilizando con propiedad la destreza expositiva por medio de argumentaciones claras, razonadas y bien fundamentadas en los textos y fuentes secundarias, conducentes a la elaboración reconclusiones críticas, y siguiendo las convenciones del sistema MLA (citas, referencias bibliográficas, etc. 3) Actitudes: 1. Gusto por la lectura de textos literarios en lengua inglesa, en cualquiera de sus géneros. 2. Interés y curiosidad intelectual por analizar y comprender textos literarios en lengua inglesa. 3. Interés y curiosidad intelectual por conocer y apreciar otras culturas, valorar su especificidad, y relacionarla de forma crítica con la propia cultura. 4. Aceptación de la incapacidad de comprender todas las palabras de un texto literario. 5. Predisposición al debate plural y fundamentado de teorías, interpretaciones y textos por medio del análisis crítico y la argumentación razonada. 6. Deseo de responsabilizarse del aprendizaje autónomo en textos literarios en lengua inglesa. 7. Predisposición a la generación de nuevas ideas. 8. Aceptación de que la interpretación hermenéutica de un texto es solamente una entre las 3 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández muchas posibles lecturas que pueda generar dicho texto. 9. Aceptación de la pluralidad intrínseca a la literatura, y asimilación de la diversidad de voces, Página 4 ideologías, realidades y visiones del mundo representadas y generadas por los textos literarios 3.- ACTITUD 3.1. Del profesor: La profesora se mostrará amable y respetuosa en el trato personal, así como firme y exigente en el trato profesional. Estará receptiva a la expresión de todo tipo de ideas y opiniones relacionadas con la asignatura siempre y cuando se expresen desde el respeto. Responderá en la medida de lo posible a todas las cuestiones que se planteen y fomentará la participación en clase. Evaluará de forma objetiva, clara y justa y explicará la aplicación de los criterios de evaluación de cada actividad a cada caso concreto que así lo solicite. Será accesible en su despacho durante su horario de tutorías, y de manera más flexible a través del “Tablón de Docencia” y el correo electrónico. 3.2. Del Profesional en Formación: Del profesional en formación se espera que prepare con antelación las tareas programadas de lectura, trabajo individual y trabajo en grupo; que esté atento al desarrollo de las sesiones; que pregunte las cuestiones que no sepa o comprenda con claridad; que sea disciplinado y previsor; que sea respetuoso con sus compañeros y con la profesora; que colabore de forma activa y constructiva; que sea claro en sus exposiciones y meticuloso en su trabajo. 4.- METODOLOGÍA. Actividades formativas: - Clases presenciales de carácter teórico/práctico - Seminarios, talleres, - Actividades académicamente dirigidas Estas actividades se desarrollarán íntegramente en inglés. Las actividades que integran el trabajo personal del alumno con el objetivo de facilitar la adquisición de las competencias de esta materia se distribuirán en los siguientes porcentajes: - Actividades presenciales: 30%. - Actividades no presenciales: 60%, dedicadas a: estudio, lecturas de textos, búsqueda bibliográfica, redacción de trabajos, preparación de casos/tareas, trabajo autónomo del alumno, seminarios, tutorías. - Evaluación: (10%). - Exámenes escritos, presentación de trabajos, tutorías de evaluación, evaluación formativa. En las clases presenciales se utilizará una metodología que estimule la participación activa del alumno con el objetivo de facilitar a los estudiantes la construcción significativa de la trama semántica de la materia y el desarrollo de las competencias relacionadas con la utilización de dicha trama tanto en el análisis crítico como en la resolución de problemas. Para tal fin, la metodología se caracterizará por: -El uso de estrategias docentes diversas: Clases expositivas (que incorporan el uso de tecnologías audiovisuales), debates, estudios de caso, trabajo cooperativo, análisis, lecturas, etc. -El uso de técnicas que fomenten la discusión y la reflexión sobre aspectos teóricos y prácticos con el objetivo de fomentar la evaluación crítica tanto de las diferentes concepciones teóricas como de su aplicación práctica. -La integración de teoría y práctica. -La revisión/ discusión de bibliografía secundaria y otros materiales previamente acordados. 4 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández -El trabajo colaborativo que permita el desarrollo de competencias relacionadas con el trabajo y la coordinación entre e intra grupos para la toma de decisiones que afecten al proyecto del trabajo en su conjunto. La incorporación de las nuevas tecnologías, mediante el uso de las plataformas especializadas de enseñanza: Tablón de Docencia 4.1. Tipología de las Actividades y Porcentaje de Evaluación: La asignatura se organizará en: Actividades individuales fuera del aula: Preparación de las lecturas obligatorias y recomendadas, así como de las actividades relacionadas. Elaboración de 2 trabajos escritos guiados (5% de la nota total de la asignatura cada uno) Actividades Individuales en el aula: Participación activa en las sesiones teóricas y prácticas (10% de la nota final de la asignatura) Tutorías: servirán para orientar el trabajo del alumnado, así como para profundizar en aspectos concretos de la materia. Actividades evaluativas: 2 Mock Exams (5% de la nota total de la asignatura cada uno) 1 Examen final (70% de la nota final de la asignatura) 4.2. Plataforma Virtual: La asignatura utilizará como soporte la plataforma Tablón de Docencia de la Universidad de Granada, que se utilizará para la organización y gestión de la asignatura en sus aspectos de notificación oficial, publicación de calificaciones, y almacenamiento de materiales didácticos. Para tener acceso a la plataforma únicamente es necesario escribir DNI/contraseña. Una vez dentro es necesario elegir la asignatura para tener acceso. La profesora también podrá establecer contacto con el alumnado de forma individual a través del correo electrónico institucional (nunca a través de otras direcciones de correo personales).1 Se recomienda la revisión diaria tanto del tablón de docencia de la asignatura, como del correo institucional. 4.3. Dinámica de clase: El alumnado deberá preparar las actividades semanales con antelación. Las sesiones se organizarán en dos bloques de 50 minutos con un breve descanso entre ellos para las sesiones de 120 minutos. El ambiente de trabajo será de distendido esfuerzo, cordialidad y respeto mutuo por las opiniones y diferencias de todos los participantes en el curso. 5.- Contenidos THEORY: 1. The Romantic Period 1.1. Romantic poetry 1.1.1. First generation of Romantic poets: Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge 1.1.2. Second generation of Romantic poets: Keats, Shelley, Byron. 1 Para obtener una dirección de correo electrónico institucional ugr, accede a la página inicial de la Universidad de Granada http://www.ugr.es y entra en ACCESO IDENTIFICADO. Selecciona la opción ALUMNO, introduce tu DNI y tu contraseña (4 dígitos). Entra en CSRIC (parte inferior) y en CORREO ELECTRÓNICO para registrarte. Utiliza un login profesional (Juan Gómez, jgomez) pues será tu carta de presentación para todo el profesorado. 5 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández 1.2. Fiction: The novels of Jane Austen and Mary Shelley: (Frankenstein). 2. The Victorian Period 2.1. Early Victorian Novelists: Dickens (Hard Times), the Brönte sisters, William Thackeray. 2.2. Children’s Literature: Lewis Carroll. 2.3. Victorian Poetry: Matthew Arnold, the Brownings, the Rossettis, Tennyson. 2.4. Industrial Fiction and Social Realism 2.5. Utilitarianism, Spiritualism (John Stuart Mill y de Jeremy Bentham) and Aestheticism (Walter Pater) 2.6. Late Victorianism: Oscar Wilde, PRACTICE: 3. In-depth analysis of poems from the Romantic period. In-depth study of a novel: Hard Times by Charles Dickens. 4. Analysis of extracts from works by prominent English novelists. In-depth study of a Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. In-depth analysis of poems from the Victorian period. 6. EVALUATION. 6.5.1. Active Participation in Class: 10% 6.5.2. Written tasks: 10% Frankenstein: 50% Hard Times : 50% A. B. 6.5.3. Mock Exams: 10% A. B. Romanticism: 5% Victorianism: 5% 6.5.4. Final Exam: 70% A. B. C. Textual Identification (%), Short Questions (%), Essay (%) 7.- Class Schedule. Literatura Inglesa III: Daily schedule 24 25 Wed 26 Mon 1:gr. A (no class) Tues 2:gr. A/B Wed 3 Mon 8 Tue 9 Wed 10 Mon 15 SEPTEMBER Class presentation. Contents. Evaluation methods Introduction to the Romantic period: Historical background (Whole group) Introduction (cont). Key concepts. Poetry: key poets OCTOBER Essay: Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman Fiction: Jane Austen Blake Wordsworth 6 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Tue 16 Wed 17 Mon 22 Tue 23 Wed 24 Mon 29 Tue 30 Wed 31 Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández Coleridge Keats Shelley NOVEMBER Mon 5 Tue 6 Wed 7 Mon 12 (groups A/B) Tue 13(groups A/B) Wed 14 Mon 19 Tue 20 Thur 22 Mon 26 Tue 27 Wed 28 DECEMBER Mon 3 Tue 4 Wed 5 Mon 10 Tue 11 Wed 12 Mon 17 Tue 18 Wed 19 Christmas holiday JANUARY Tue 8 (groups A & B) Wed 10 Mon14 Tue 15 Wed 17 Mon 21 Tues 22 23 Byron (groups A/B both days) In-class analysis of Frankenstein Mock Exam (no elimina temario, pero cuenta el 5% de la nota final). Hand out Frankenstein assignment Introduction to the Victorian Period: Historical Background (whole group) Utilitarianism, Aestheticism (Walter Pater) Spiritualism. Industrial Fiction and Social Realism. Charles Dickens (Intro) Bronte’s Jane Eyre Thackeray’s Vanity Fair Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland Mathew Arnold Brownings Rosettis Tennyson Hard Times Oscar Wilde Mock Exam (no elimina temario, pero cuenta el 5% de la nota final). 7 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández Hand out Frankenstein assignment 8.- Basic Bibliography. S. Greenblatt & M.H. Abrams, The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Vol. 2. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Co., 2005. Also online <http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/welcome.htm> A. Sanders, The Short Oxford History of English Literature. 2nd ed. Oxford: O.U.P., 2000. Complementary Texts: M.H Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition. Oxford: O.UP., 1972. Sir M. Bowra, The Romantic Imagination. Oxford & London: O.U.P., 1969. M. Butler, Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries. English Literature and Its Background 1760-1830. Oxford & New York: O.U.P., 1981. R.J. Cruikshank, Charles Dickens and Early Victorian England. London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons, Ltd., 1949. T. Eagleton, The English Novel. An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. A. Day, Romanticism. London & New York: Routledge, 1996. F. Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England. London: Panther, 1972. L. Miller, The Brontë Myth. London: Vintage, 2002. H.G. Shenk, The Mind of the European Romantics. London: Constable, 1966. A.N. Wilson, The Victorians. London: Arrow Books, 2003. 8 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández 1. The Romantic Period 1.1. Romantic poetry Introductory videos: 1. Romanticism: painting, composers, writers <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zADECqE9BE> 2. “What is romanticism?” <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DdqD_a1ox74> 3. BBC: “The Romantics: Eternity” <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3lBUvbLYMU> 4. BBC: “The Romantics: Nature” <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BhOyI-SjU-g> 5. BBC: “The Romantics: Liberty” <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMA85_IkFxg&feature=relmfu> 9 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández 1.1.1. First generation of Romantic poets: Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge. 1.1.1.1. William Blake (1757-1827): Introductory video: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sk_geYnyuOk> Also check: "William Blake."Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004.Encyclopedia.com.9 Aug. 2012<http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/William_Blake.aspx>. Main topics: imagination, visions, spiritual and social issues. Two Letters on Sight and Vision Find them <http://es.scribd.com/doc/20903052/Keyne-theLetters-of-William-Blake> Blake wrote each of these pronouncements about the difference between “corporeal” sight and imaginative vision at a time when a patron was putting pressure on him to turn from his visionary art to more fashionable modes of representation. 1. [To Dr. John Trusler, August 23, 1790] The first letter is a passionate response to John Trusler, clergyman, bookseller, and author, who had objected to Blake’s illustrations for one of Trusler’s books. [To Dr. John Trusler, August 23, 1799] What is Blake’s argument against simplicity? Which other forms of pictorial art does Blake mention in this letter? What is his opinion about them? What is for Blake, the relation between “This World” and “Fancy”? What is the connection between children and Blake’s paintings? 2. [To Thomas Butts, November 22, 1802] The second letter was addressed to Thomas Butts, a staunch supporter who, though only a chief clerk in the Public Record Office, bought more of Blake’s 10 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández works than did any other contemporary. To this friend, Blake expresses his anguish at the demands of William Hayley, a well to do writer and patron of the arts who, after having settled the Blakes at Felpham in Sussex, was trying to impose on the artist, for what he thought were Blake’s best interests, his own conventional standards and tastes. The letter includes the poem “With Happiness Stretchd Across the Hills,” that Blake had composed a year before the letter. The center of the poem is the confrontation with his father, who appears first as a numinous presence and is then seen as a thistle, which in its inner reality is a gray old man, standing in his path. Blake destroys the thistle and in doing so destroys the power which the image of his father still exerts over him. As a result, a supreme awareness of confidence and maturity is released in Blake, the man and the poet. The dominant presence is now Los, the prophet and artist, whose strength becomes Blake’s own. The poem ends with a ringing affirmation of fourfold vision. Blake has freed himself of the burden of paternal domination over his achievements and his relation to society. From this time on he has a new assurance about his mission and his function. Adams considers that the theme of both this poem and an earlier one transcribed in the letters, “To my Friend Butts I write,” is “the transformation of the natural world into human forms and ultimately into a single human form” (p. 169). Commentary: What do you think the poem is about? Consider the “Thistle” and “Los”. Are they positive or negative visions? What do they stand for? What does the poem reveal about Blake’s artistic views? Blake shared with a number of contemporary German philosophers the point of view that man’s fall is essentially a mode of psychic disintegration and of resultant alienation from oneself, one’s world, and one’s fellow-men, and that man’s hope of recovery lies in a process of reintegration. As an imaginative poet, Blake does not present this view in abstract conceptual terms, but embodies it in picturable agents acting out an epic world. All beings, together with the world they inhabit are perceived as sharing the one life and the one humanity of the “Universal Brotherhood,” the human Form Divine, who is imagined as creating such universe by the very act of envisioning it. This lost mode of vision sees a nature which, because it is humanized, is a place where individual men, united as One Man, can feel at home. Hazard Adams, William Blake: A Reading of the Shorter Poems (Seattle: University of Washington Press, I963), pp. 173-79. 11 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández Storch, Margaret (1983) “The ‘Spectrous Fiend’ Cast Out. Blakes’ Crisis at Felpham” Modern Language Quarterly 44.2, 115-135, Songs of Innocence & Experience In the Songs of Innocence (1789) Blake assumes the stance that he is writing “happy songs/Every child may joy to hear.” They show the fallen world, however, as it appears to the limited view of a naïve and acquiescent innocence. The “contrary” vision is expressed in Songs of Experience (1794), which reveals a terrifying world of poverty, disease, prostitution, war, exploitation, and social, institutional, and sexual repression. In the best of these songs, Blake achieved his mature lyric technique of compressed metaphor and symbol which explode into a multiplicity of reference. 12 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Read the contrastive commentary of both Nurse’s songs: <http://www.utsc.utoronto.ca/~mcuddy/ENGB02Y/NurseSong.htm> 13 Prof. Miriam Fernández Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III 14 Prof. Miriam Fernández Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández Read the following commentary of “London” <http://mural.uv.es/garmaest/London%20by%20William%20Blake.htm> Which would you say are the causes of so much sorrow in Blake’s “London”? Are they the result of institutional or personal corruption? What is the symbolism of London in the poem? “The Tyger” Would you say the poem belongs to Innocence or Experience? Is the Tyger a positive or a negative symbol? What is the symbolism of the tyger? Tyger! Tyger! burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Could frame thy fearful symmetry? In what distant deeps or skies Burnt the fire of thine eyes? On what wings dare he aspire? What the hand dare sieze the fire? And what shoulder, & what art. Could twist the sinews of thy heart? And when thy heart began to beat, What dread hand? & what dread feet? What the hammer? what the chain? In what furnace was thy brain? What the anvil? what dread grasp Dare its deadly terrors clasp? When the stars threw down their spears, And watered heaven with their tears, Did he smile his work to see? Did he who made the Lamb make thee? Tyger! Tyger! burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Dare frame thy fearful symmetry? “The Lamb” <http://www.sparknotes.com/poetry/blake/section1.html> 15 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández Now compare “The Divine Image” < http://www.sparknotes.com/poetry/blake/section3.rhtml> and The Human Abstract” < http://www.sparknotes.com/poetry/blake/section8.rhtml> Which would you say is Blake’s purpose in comparing these opposite visions of reality? Read the following information on the influence of Medieval Emblems in Blake’s combination of pictorial and poetic forms: <http://webdoc.gwdg.de/edoc/ia/eese/artic22/hoeltgen/2_2002.html> What is a Medieval Emblem? How are they similar or different from Blake’s poems and visions? Is the picture an illustration of the poem or is the poem a commentary of the picture? Recommended Website: “William Blake: Religion and Psychology” <http://ramhornd.blogspot.com.es/search/label/Albion> 16 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández 1.1.1.2. William Wordsworth (1770-1850): Watch the following introductory video: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6s64nQli3eI&feature =related> Lyrical Ballads (1798) The result of Wordsworth and Coleridge’s joint efforts was a small volume, published in 1798, Lyrical Ballads, With Few Other Poems. It opened with Coelridge’s Ancient Mariner and closed with Wordsworth’s great descriptive and meditative poem in blank verse (not a “lyrical ballad,” but one of the “other poems” of the title), Tintern Abbey. So close was their association that they lost almost all sense of individual proprietorship in a composition. We find the same phrases occurring in poems of Wordsworth and Coleridge, as well as in the remarkable journals that Dorothy kept at the time. Wordsworth is above all, the poet of the remembrance of things past, or as he himself put it, of “emotion recollected in tranquillity.” Some object or event in the present triggers a sudden renewal of feelings he had experienced in youth; the result is a poem exhibiting the sharp discrepancy between what Wordsworth called “two consciousnesses”: himself as he is now and as he once was. Introduction: “Melvyn Bragg and his guests discuss Lyrical Ballads” BBC Radio 4, 8 March 2012 <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zirOcbd9PEA> 1. What is pantysocracy? 2. What is the internal contradiction in the title of the book? Recommended Lecture: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OTfiEHm3_pQ&feat ure=endscreen&NR=1> Preface to Lyrical Ballands Wordsworth published over his own name a new edition of Lyrical Ballads, dated 1800. In his famous preface to this edition, planned, like so many poems, in close consultation with Coleridge, Wordsworth enunciated the principles of the new criticism which served as rational for the new poetry. The preface was enlarged for the third edition, published two years later. Most discussions of the Preface have focused 17 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández on Wordsworth’s assertions about the valid language of poetry, on which he bases his attack on the “poetic diction” of 18th c poets. Wordsworth undertook to overthrow the basic theory, as well as the reigning practice, of neoclassic poetry. His Preface implicitly denies the assumption that the poetic genres constitute a hierarchy, from epic and tragedy at the top down through comedy, satire, pastoral, and the short lyric at the lower reaches of the poetic scale, and he rejects the traditional principle of “decorum,” according to which the subject matter (especially the social class of te protagonists) and the level of diction of a poem must conform to the status of the literary kind on the poetic scale. When Wordsworth asserted in the Preface that he deliberately chose to represent “incidents and situations from common life,” he translated his democratic sympathies into critical terms, justifying his use of peasants, children, outcasts, criminals, and idiot boys as serious subjects of poetic and even tragic concern. He also undertook to write in “a selection of language really used by men,” on the ground that there can be no “essential difference between the language of prose and metrical composition.” Wordsworth subverted the neoclassical principle that the language of poem must be elevated over standard speech by a special diction and by artful figures of speech, in order to match the language to the height and dignity of a particular genre. The valid language of poetry is based on the new radical premise that “all good poetry is the spontaneous flow of powerful feelings” even though the process is influenced by prior thought and acquired poetical skill. The equivalence between the valid language of poems and the prose language “really spoken by men” is not one of vocabulary nor of syntax, but an equivalence in emotional genesis—both, according to Wordsworth, are not contrived and artful reconstructions, but originate spontaneously, as the words and figures which, as Keats later put it, are “the true voice of feeling.” Wordsworth’s assertions have been immensely influential in expanding the range of serious literature to include the common man and ordinary things and events, as well as in justifying a poetry of sincerity rather than of artifice, expressed in the ordinary language of its time. He attributed to imaginative literature the primary role in 18 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández keeping man emotionally alive and morally sensitive—that is, keeping him essentially human—in the face of the pressures of a technological and increasingly urban society, with its mass media and mass culture that threaten, as he presciently foresaw, to blunt the mind’s “discriminatory powers” and to “reduce it to a state of almost savage torpor.” The values which permeate his Preface are the central humanistic values of the 18thcentury enlightenment—that is, the normative reference to that which is essential, simple, universal, and permanent in human nature. To Wordsworth, the great poet is not the practitioner of an artistic craft designed to satisfy the refined “taste” of a literary connoisseur. He affirms the primal human values—the joy of life, reverence for all manifestations of life, and the grandeur of the pleasure-principle which is the expression of the life-force and the natural sign of any activity that enhances life. In opposition to all the modern forces that tend to divide—or, as we now say, to “alienate”—man from his own essential nature, from outer nature, and from his fellow men, Wordsworth places the burden of sustaining human connection primarily on the poet: “He is the rock of defense of human nature; an upholder and preserver, carrying everywhere with him relationships and love.” Read the Preface <http://www.english.upenn.edu/~jenglish/Courses/Spring2001/040/preface1802.html> and find in the text the excerpts that express the following ideas: 1. The mission of the poet is to transmit pleasure and thus pay homage to the dignity of man as he acknowledges the beauty of the universe. 19 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández 2. The purpose of his poems is to use common language to express an unusual, exalted vision of everyday life that is represented to the poet in the natural way of a free association of ideas. 3. Poetic language should adapt to the popular uses and tastes. 4. Poetry is a balance between profound reason and feeling. 5. Excess in art is a consequence of the industrial revolution that favours the superficial over the essentially human. 6. Wordsworth would dislike Blake’s poetry. 7. The object of poetry is eternal truth; poetry is the first and last of all knowledge. Tintern Abbey < http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n_k66TJ8gLc> The poem makes use of the freedom of blank verse (no rhyming) as well as the measured rhythm of iambic (an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable) pentameter (with a few notable exceptions). The flow of the writing has been described as that of waves, accelerating only to stop in the middle of a line (caesura). The repetition of sounds and words adds to the ebb and flow of the language, appropriately speaking to the ebb and flow of the poet's memories. Nature is described with almost religious fervor. While Wordsworth uses many words related to spirituality and religion in this poem, he never refers to God or Christianity. It seems that nature is playing that role in this poem. Nature, it seems, offers humankind ("we") a kind of insight ("We see into the life of things") in the face of mortality ("we are laid asleep"). As in many of his other poems, Wordsworth personifies natural forms or nature as a whole by addressing them directly (apostrophe). Nature is not only an object of beauty and the subject of memories, but also the catalyst for a beautiful, harmonious relationship between two people, and their memories of that relationship. This falls in line with Wordsworth's belief that nature is a source of inspiration and harmony that can elevate human existence to the level of the sublime in a way that civilization cannot. Find in the poem the lines that exemplify the words in bold. 20 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández What would you say is the “sense sublime” in line 95? Read the following poems and consider the relation existing between the natural and human components that appear in them. I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud <http://www.bartleby.com/145/ww260.html> She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways <http://www.bartleby.com/145/ww147.html> The Solitary Reaper<http://www.bartleby.com/145/ww240.html> It is a Beauteous Evening <http://www.bartleby.com/145/ww211.html> Are they similar or contrary? Does nature serve as a mere background frame or as something else? Is there a metaphorical relation between some of them? Watch short video about the Wordsworths-Coleridge relation: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PMu615i8tE8> Dorothy Wordsworth exerted an important influence on the lives and writings of both her brother and S.T. Coleridge. It is now apparent that she also possessed a power exceeding that of the two poets for precise observation of people and the natural world, together with a genius for terse, luminous, and delicately nuanced description in prose. Read the following excerpts from her Alfoxden Journal and try to find similarities in subject and style with “Tintern Abbey.” From The Alfoxden Journal of Dorothy Wordsworth (1771-1855) Jan. 31, 1798. Set forward to Stowey at half-past five. A violent storm in the wood ; sheltered under the hollies. When we left home the moon immensely large, the sky scattered over with clouds. These soon closed in, contracting the dimensions of the moon without concealing her.2 The sound of the pattering shower, and the gusts of wind, very grand. Left the wood when nothing remained of the storm but the driving wind, and a few scattering drops of rain. Presently all clear, Venus first showing herself between the struggling clouds; afterwards Jupiter appeared. The hawthorn hedges, black and pointed, glittering with millions of diamond drops; the hollies shining with broader patches of light. The road to the village of Holford glittered like another stream. On our return, the wind high a violent storm of hail and rain at the Castle of Comfort. All the Heavens seemed in one 2 See Coleridge’s Christabel, lines 16-19. 21 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández perpetual motion when the rain ceased; the moon appearing, now half veiled, and now retired behind heavy clouds, the stars still moving, the roads very dirty. Feb. 3. A mild morning, the windows open at breakfast, the redbreasts singing in the garden. Walked with Coleridge over the hills. The sea at first obscured by vapour ; that vapour afterwards slid in one mighty mass along the sea-shore ; the islands and one point of land clear beyond it. The distant country (which was purple in the clear dull air), overhung by straggling clouds that sailed over it, appeared like the darker clouds, which are often seen at a great distance apparently, motionless, while the nearer ones pass quickly over them, driven by the lower winds. I never saw such a union of earth, sky, and sea. The clouds beneath our feet spread them-selves to the water, and the clouds of the sky almost joined them. Gathered sticks in the wood; a perfect stillness. The redbreasts sang upon the leafless boughs. Of a great number of sheep in the field, only one standing. Returned to dinner at five o'clock. The moonlight still and warm as a summer's night at nine o'clock. Feb. 4. Walked a great part of the way to Stowey with Coleridge. The morning warm and sunny. The young lasses seen on the hill-tops, in the villages and roads, in their summer holiday clothes pink petticoats and blue. Mothers with their children in arms, and the little ones that could just walk, tottering by their side. Midges or small flies spinning in the sunshine ; the songs of the lark and redbreast; daisies upon the turf; the hazels in blossom ; honeysuckles budding. I saw one solitary strawberry flower under a hedge. The furze gay with blossom. The moss rubbed from the pailings by the sheep, that leave locks of wool, and the red marks with which they are spotted, upon the wood.3 From The Grassmere Journal, 15 April 1802. Thursday 15th. It was a threatening misty morning—but mild. We set off after dinner from Eusemere. Mrs Clarkson went a short way with us but turned back. The wind was furious and we thought we must have returned. We first rested in the large Boat-house, then under a furze Bush opposite Mr Clarkson's. Saw the plough going in the field. The wind seized our breath the Lake was rough. There was a Boat by itself floating in the middle of the Bay below Water Millock. We rested again in the Water Millock Lane. The hawthorns are black and green, the birches here and there greenish but there is yet more of purple to be seen on the Twigs. We got over into a field to avoid some cows—people working, a few primroses by the roadside, woodsorrel flower, the anemone, scentless violets, strawberries, and that starry 3 See Wordsworth’s The Ruined Cottage, lines 330-336. 22 Grado en Estudios Ingleses Literatura Inglesa III Prof. Miriam Fernández yellow flower which Mrs C. calls pile wort. When we were in the woods beyond Gowbarrow park we saw a few daffodils close to the water side. We fancied that the lake had floated the seeds ashore and that the little colony had so sprung up. But as we went along there were more and yet more and at last under the boughs of the trees, we saw that there was a long belt of them along the shore, about the breadth of a country turnpike road. I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about and about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness and the rest tossed and reeled and danced and seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the lake, they looked so gay ever glancing ever changing. This wind blew directly over the lake to them. There was here and there a little knot and a few stragglers a few yards higher up but they were so few as not to disturb the simplicity and unity and life of that one busy highway. We rested again and again. The Bays were stormy, and we heard the waves at different distances and in the middle of the water like the sea. Rain came on—we were wet when we reached Luffs but we called in. Luckily all was chearless and gloomy so we faced the storm—we must have been wet if we had waited—put on dry clothes at Dobson's. I was very kindly treated by a young woman, the Landlady looked sour but it is her way. She gave us a goodish supper. Excellent ham and potatoes. We paid 7/ when we came away. William was sitting by a bright fire when I came downstairs. He soon made his way to the Library piled up in a corner of the window. He brought out a volume of Enfield's Speaker, another miscellany, and an odd volume of Congreve's plays. We had a glass of warm rum and water. We enjoyed ourselves and wished for Mary. It rained and blew when we went to bed. N.B. Deer in Gowbarrow park like skeletons. 23