Ecosystem Services - Department of Philosophy

advertisement

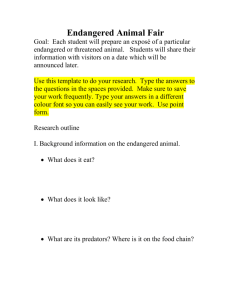

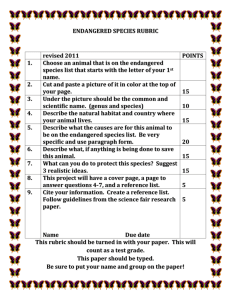

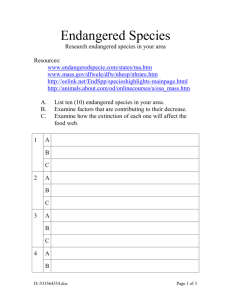

Ecosystem Services • Biodiversity • Climate • Mitigation of floods and droughts • Services provided by soil • Pollination • Pest control • Seed dispersal • Aesthetic beauty Quic kTime™ and a dec ompres sor are needed to see this pic ture. BIOSPHERE 2 Biosphere 2 • 3.15-acre artificial closed ecological system outside Tucson • It included a rainforest, mini-ocean, coral reef, mangrove wetlands, savannah grassland, desert, farm, and living quarters and offices • First mission: 9-26-1991 to 9-261993, 8 people • Second mission: 3-6-94 to 9-6-94, aborted Problems • Despite $200 million invested, impossible to sustain the 8 people without continual help from the outside. – O2 concentration dropped to 14% – Spikes in CO2 – Nitrous oxide concentrations high enough to cause brain damage – Extinctions (19/25 vertebrates, all pollinators) – Wild overgrowth of vines and various insect populations Both missions, and especially the second, experienced many, many social and organizational problems. “Overriding scientific lessons from Biosphere 2 already may be available. To many of us, healthy ecosystems and biodiversity have inestimable aesthetic value, but such philosophical orientations are difficult to translate into the kinds of economic terms that carry weight with business or industrial interests. Some far-thinking economists have sought to attach dollar values to natural ecosystems by virtue of the fundamental lifesupport services rendered (e.g., atmospheric regulation by rainforests and oceans, water purification by marshes, groundwater storage by aquifers, soil generation and maintenance by decomposers), but such at- tempts are almost hopelessly complicated by the vast range of spatial and temporal scales over which the monetary valuations might be tabulated. However, thanks to the controlled experiment of Biosphere 2 we now have a more explicit ledger. .. …”The cost of the man-made technosphere that (marginally) regulated life-support systems for eight Biospherians over two years was about $150 million, or $9,000,000 per person per year. These services are pro- vided to the rest of us more-orless cost-free by natural processes, but if we were being charged, the total invoice for all Earthospherians would come to an astronomical three quintillion dollars for the current generation alone! The sad irony is that, as a species, we blithely take these eco- system services for granted, acting as though we can endlessly befoul and overpopulate our planet.” --John Avise, “The Real Message From Biosphere 2” The problem It’s widely agreed that there is a biodiversity crisis. Legislation and treaties are enacted to help stop it. But what is biodiversity, and why do we value it? Should we value it? QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. • Endangered Species Preservation Act, 1966: required a list to be made of endangered species and money to be set aside for purchase of habitat to protect them--but no provisions included against harming endangered animals. • Endangered Species Conservation Act, 1969: required two lists, of foreign and of native, endangered species; foreign species on the list were not allowed into the country, and species native or foreign could not be bought or sold if illegally taken. “The stated purposes of the ESA are: “to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved, to provide a program for the conservation of such endangered species and threatened species, and to take such steps as may be appropriate to achieve the purposes of the treaties and conventions [on international trade in endangered species] (Sec. 2(b)). Certainly the best-known impact of the ESA is the establishment of broad prohibitions against any take of endangered and threatened animal species. However, another major intention of the act is to integrate federal and international legislation on endangered species, including the national-level implementation of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna, 1973). Within this structure, the ESA establishes guidelines to define categories and listing protocols for endangered and threatened species (Sec. 4). In addition, the act defines the concept of "critical habitat". Federal agencies are required to (a) actively promote the conservation of listed species; and (b) avoid any actions that would have negative effects on listed species and their critical habitat. Finally, the ESA provides matching federal funds for some state actions in support of the act and authorizes the acquisition of land for plants and animals listed under CITES.” Endangered Species Act 1973 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. gives the FWS and NMFS authority to list species that are either "endangered" or "threatened" (likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future), requires that federal agencies and departments through their own actions or actions funded or permitted by them must not jeopardize the continued existence of a listed species or its habitat, declares it unlawful to "take" an endangered or threatened species within the U.S., its territorial waters, or on the high seas, provides Interior and Agriculture with authority and funds to acquire habit of endangered or threatened species, provides for criminal penalties, including seizure of equipment used in takings, and provides standing to citizens to bring suit under the ESA. QuickTime™ and a d eco mpres sor are nee ded to s ee this picture. Endangered Species Act 1973 (Go to ESA pdf…) How does a species get listed as an endangered or threatened species? • • • First, the public, the Fish and Wildlife Service, biologists, or other governmental agencies, propose a species for the list. The public is offered the opportunity to comment about the proposal, and the rule is finalized (or withdrawn). Species to be listed are selected by the Fish and Wildlife Service from a list of candidates and are recognized using a priority system. QuickTime™ and a TIF F (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. • • • • • • • • • • • Bald Eagle (increased from 417 to 9,250 pairs between 1963 and 2006) Whooping Crane (increased from 54 to 436 birds between 1967 and 2003) Kirtland's Warbler (increased from 210 to 1,415 pairs between 1971 and 2005) Peregrine Falcon (increased from 324 to 1,700 pairs between 1975 and 2000) Gray Wolf (populations increased dramatically in the Northern Rockies, Southwest, and Great Lakes) Gray Whale (increased from 13,095 to 26,635 whales between 1968 and 1998) Grizzly bear (increased from about 271 to over 580 bears in the Yellowstone area between 1975 and 2005). Californiaユs Southern Sea Otter (increased from 1,789 in 1976 to 2,735 in 2005) San Clemente Indian Paintbrush (increased from 500 plants in 1979 to more than 3,500 in 1997) Florida's Red Wolf (increased from 17 in 1980 to 257 in 2003)・ Few species have become extinct while listed under the Endangered Species Act, and 93% have had their population sizes increase or remain stable since being listed as threatened or endangered. Currently 1,312 species are listed. • As of today in the United States there are 92 listed endangered species (357 animals and 567 plants). • There is a total of 256 listed threatened species in the United States (121 animals and 135 plants). • Of the 924 endangered species in the United States, 70 are endangered and 40 are threatened species of fish. • Plants represent the largest group, followed by birds, fishes, mammals, and clams/mussels. Controversy • Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (1978). • A project that had already progressed substantially before the discovery of a listed species on the site eventually led to amendments to the ESA and associated regulations and to the creation of the Endangered Species Committee and an exemption process from section 7. More directly, this ruling determined that the TVA’s ignorance of the existence of the species at the project site did not excuse it from following the protocols required by the ESA; in addition, the idea that economic factors might be taken into account in complying with the ESA was flatly rejected, as was the idea that continued congressional funding of a project effectively exempted the project from ESA compliance. • Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapt. Comms. for Ore., 515 U.S. 687 (1995) • The Supreme Court found that in addition to making it a crime to "take" a listed species, section 9 also prohibits the destruction of habitat of such a species. The legislative definitions of "take" and "harm" are sufficiently broad to include the degradation or destruction of a species’ habitat. • A species is "any subspecies of fish or wildlife or plants, and any distinct population segment of any species of vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature." 16 U.S.C. § 1532(16). • http://www.mrsc.org/environment/esa/esa prime.htm (explains ESA) • http://endangered.fws.gov/esa.html (statement of ESA) • 99% of the time the Government has found (in over 120,000 consultations) the species of concern was not in jeopardy. • There are about 632 officially endangered species (326 plants) and 190 threatened species in the U.S. What is a Species? • We want to know what to worry about, what to conserve. The mallard duck was introduced into Australia and New Zealand. It mates with the native Pacific grey drakes. Because more aggressive and adaptable, the mallard may eliminate the Pacific grey drake as a distinctive duck. Is this bad? Taxonomy Taxonomy: species (sapiens), genus (Homo), family (hominid), order (primates), class (mammal), phylum (chordate), kingdom (animal) 1. phenetic species concept: a measure of morphological, genetic or behavioral similarity. Species are groups of similar organisms. Makes species a conventional distinction Males, females, juveniles may differ markedly in appearance/behavior 2. biological species concept: a species is a group wherein genes flow freely. If X and Y are two species, X is reproductively isolated from Y. The notion of potentially interbreeding is slippery 3. phylogenetic species concept: a species is a lineage of ancestral/descendant population. How do we count lineages? Both 2 and 3 are “historical” definitions. No intrinsic property makes you or anything a member of a species. Problem 1.5 million species have been catalogued. It is thought that there are currently 10 and 100 million that exist on Earth. • Between 1600 and 1900: one species goes extinct per 4 yrs • Between 1900 and 1960: one species goes extinct per 1 yr • Between 1960 and now: estimates vary from 100 per yr to 40,000 per yr! QuickTime™ and a d eco mpres sor are nee ded to s ee this picture. • Amazon: 2.7 million square miles (about 90% size of continental U.S.). The Amazon River is 4000 miles long and puts 170 billion gallons of water into the Atlantic per hour. In a small area of the forest one might find: 750 tree species, 125 mammal species, 400 bird species, 60 amphibian species, and 400 insect species (in just one tree). 30% of all the world’s bird species are here. • Terry Erwin’s “bug bomb” gave estimates of 8 million types of beetle and 30 million species of tropical arthropods in one small area. • Hawaii: since first human contact, as many as half of the birds have gone extinct. Out of 135 current species of bird, only about a dozen are doing well. Another dozen are virtually extinct, another dozen endangered. • 80,000 acres square miles of forest lost each yr (World Resources Institute; U.N.) • In U.S. the National Biological Service (Feb 1995) reported that during last century half of our country’s ecosystems had been degraded to the point of endangerment. • There exist various models (e.g., by MacArthur and Wilson, Harvard, 1963) that allow one to predict the effect on species of deforestation. Assuming the number of species doubles with every tenfold increase in area, reducing tropical forests to 10% of what they were will reduce 50% of the earth’s species. Estimated 17,000 – 100,000 species per yr lost • “Homo sapiens is poised to become the greatest catastrophic agent since a giant asteroid collided with the earth sixty-five million years ago, wiping out half the world’s species in a geological instant.” (Richard What is a Species? • “(15) The term "species" includes any subspecies of fish or wildlife or plants, and any distinct population segment of any species or vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature.” •Typological/morphological speciesハA group of organisms in which individuals are members of the species if they sufficiently conform to certain fixed properties. The clusters of variations or phenotypes within specimens (ie: longer and shorter tails) would differentiate the species. This method was used as a "classical" method of determining species, such as with Linnaeus early in evolutionary theory. However, we now know that different phenotypes do not always constitute different species (e.g.: a 4-winged Drosophila born to a 2-winged mother is not a different species). Species named in this manner are called morphospecies. • Biological / Isolation speciesハA set of actually or potentially interbreeding populations. This is generally a useful formulation for scientists working with living examples of the higher taxa like mammals, fish, and birds, but meaningless for organisms that do not reproduce sexually. It does not distinguish between the theoretical possibility of interbreeding and the actual likelihood of gene flow between populations and is thus impractical in instances of geographically isolated populations. • Phylogenetic / Evolutionary / Darwinian speciesハA group of organisms that shares an ancestor; a lineage that maintains its integrity with respect to other lineages through both time and space. At some point in the progress of such a group, members may diverge from one another: when such a divergence becomes sufficiently clear, the two populations are regarded as separate species. Subspecies as such are not recognized under this approach; either a population is a phylogenetic species or it is not taxonomically distinguishable. Biological Species Concept The biological species concept defines a species as members of populations that actually or potentially interbreed in nature, not according to similarity of appearance. Although appearance is helpful in identifying species, it does not define species. QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Unc ompressed) decompres sor are needed to see this picture. Appearance isn’t everything Organisms may appear to be alike and be different species. For example, Western meadowlarks (Sturnella neglecta) and Eastern meadowlarks (Sturnella magna) look almost identical to one another, yet do not interbreed with each other—thus, they are separate species according to this definition. The Western meadowlark and the Eastern meadowlark appear to be identical, and their ranges overlap, but their distinct songs prevent interbreeding.t interbreeding. QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Unc ompressed) decompres sor are needed to see this picture. Organisms may look different and yet be the same species. For example, look at these ants. You might think that they are distantly related species. In fact, they are sisters—two ants of the species Pheidole barbata, fulfilling different roles in the same colony. Many characteristics can vary within a single species. For example, the plant hydrangea may have pink “flowers”— they’re actually modified leaves—or blue “flowers.” But that doesn’t mean that we should classify the two forms as different species. In fact, you could cause a blue-“flowered” plant to become a pink-“flowered” plant just by changing the pH of the soil and the amount of aluminum taken up by the plant. QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. The Crisis QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. • Ranges of current extinctions are 100–10,000 times the prehuman level of roughly one species out of a million each year. Most estimates are closer to 1,000 times the prehuman level (equal to 0.1% per year or 5% over 50 years), but the rate is rising. In The Diversity of Life, E.O. Wilson uses conservative values to scale species loss to area reduction and the rate of tropical deforestation. He arrives at about 0.25% of tropical forest species extinguished or committed to early extinction annually (Wilson 1999, p. 280). Since most species likely occur in tropical forests, these ecosystems are a good proxy: even if no extinction occurred elsewhere, the planetary rate would still be 1,000 times prehuman levels. (What do we mean by メcommitted to early extinctionモ? Studies from forests show that when forests are reduced to even large fragments, then 10ミ50% of the species go extinct within 100 years (see footnote above). The areadependent decline in mammal species in national parks also accords with the picture of committed extinction by a real reduction alone (Newmark 1996) . Species-Area Curve QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture.