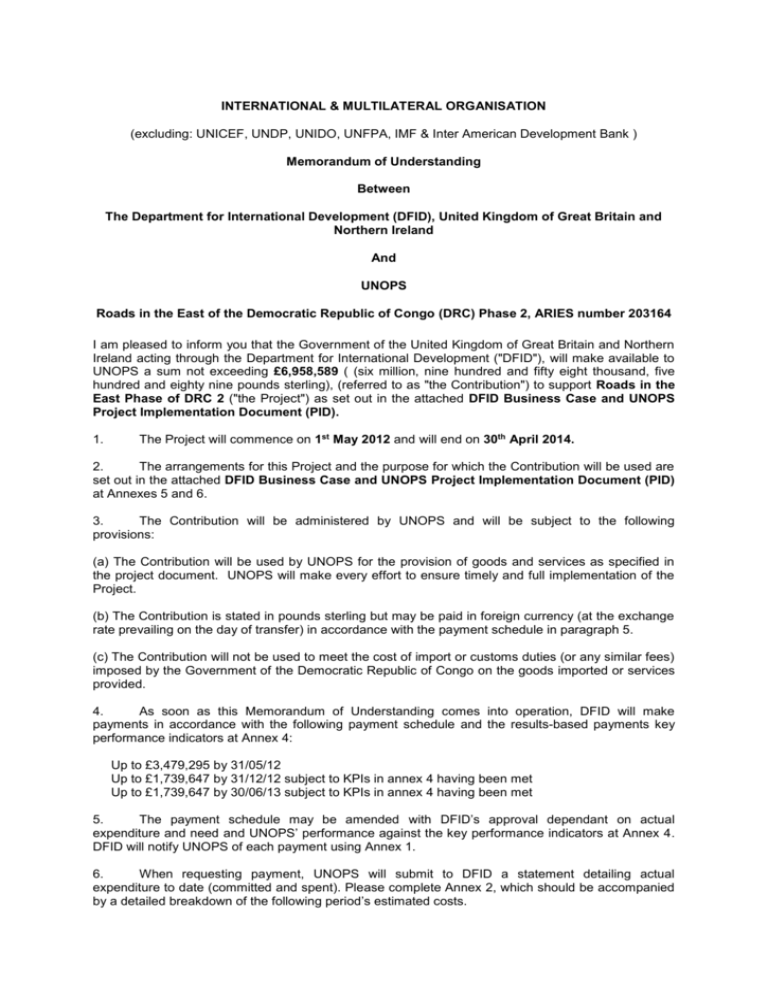

MOU - International and Multilateral Organisation

advertisement