Psyc 6356 Clinical Assessment I - Florida Center for Reading

Assessing Academic Literacy:

The role of text in comprehending written language

Barbara Foorman, Ph.D.

Florida Center for Reading

Research

Florida State University

1

What are the Issues?

• Academic literacy assumes grade-level proficiency.

• On the 2007 Reading NAEP, 33% below basic in G4; 26% below basic in G8.

• For minorities, the % below basic on the 2007

Reading NAEP are: 53% in G4 & 45% in G8 for Blacks; 50% in G4 and 42% in G8 for

Hispanics.

• NCLB requires that students at-risk for reading disability receive intervention.

2

Goals for This Presentation

Explain relation of academic literacy to academic language

Definitions of reading comprehension

Characteristics of text difficulty

Measuring text difficulty

Assessing academic literacy

3

Academic Language is at the Core of Literacy Instruction

Word Meanings

Text a. because it allows literate people to discuss literary products; previously referred to as extended discourse or decontextualized language.

b. because contextual cues and shared assumptions are minimized by explicitly encoding referents for pronouns, actions, and locations

4

13 higher-

SES children

(professional)

23 middle/lower-

SES children

(working class)

6 welfare children

Age of child in months

5

Hart & Risley, 1995

Language Experience

Professional

Working-class

Welfare

Age of child in months

6

Hart & Risley, 1995

Quality Teacher Talk

(Snow et al., 2007)

• Rare words

• Ability to listen to children and to extend their comments

• Tendency to engage children in cognitively challenging talk

• Promotes emergent literacy & vocabulary & literacy success in middle grades

7

Home & School experiences: ages 3-6 Skills developed: ages 3-6 School performance

Literacy

Print focus

Understanding literacy

Kindergarten and first grade reading

Conversation

Extended discourse forms and nonfamiliar audiences

Conversational language

Decontextualized language

Instruction and

Practice in reading

Reading comprehension

In Grade 4

(Snow, 1991)

8

Table 3

50

40

30

20

10

2

% Independent

98

90

80

70

60

Reading

Minutes Per Day

65.0

21.1

14.2

9.6

6.5

4.6

3.3

1.3

0.7

0.1

0.0

Words Read Per

Year

4,358,000

1,823,000

1,146,000

622,000

432,000

282,000

200,000

106,000

21,000

8,000

0

Variation in Amount of Independent Reading

Is Literacy Enough?

(Snow et al., 2007)

For adolescents, oral language and literacy skills need to be adequate, but also need:

• Caring adult(s) at home

• Caring adults at school who provide guidance about how to meet goals (often need smaller school)

• Minimal risk: Not many school transitions; minimal family disturbances.

10

What is Reading Comprehension?

• “the process of simultaneously extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language” (RAND, 2002, p. 11)

• “Reading is an active and complex process that involves

– Understanding written text

– Developing and interpreting meaning; and

– Using meaning as appropriate to type of text, purpose, and situation” (NAEP Framework,

2009) 11

Text structure, vocabulary, genre discourse, motivating features, print style and font

Word recognition, vocabulary, background knowledge, strategy use, inference-making abilities, motivation

TEXT READER

ACTIVITY

Environment, cultural norms

Purpose, social relations, school/classroom/peers/ families

A heuristic for thinking about reading comprehension (Sweet & Snow, 2003).

12

Understanding what has been read; the application to written text of:

(a) nonlinguistic

(conceptual) knowledge

(b) general language comprehension skills

(Rayner, Foorman, Perfetti, Pesetsky, &

Seidenberg, 2001)

13

The Reading

Pillar

Skilled Reading

(NRC, 1998 )

Speed and ease of reading with comprehension

Print Awareness & Letter

Knowledge

Motivation to Read

Oral Language including

Phonological Awareness

Fluency

Comprehension

Conceptual

Knowledge/vocabulary

Strategic processing of text

Word Recognition

Emergent Reading

Decoding using alphabetic principle

Decoding using other cues

Sight Recognition

14

What Makes a Text Difficult?

15

Components of Reading Comprehension

(Perfetti, 1999)

Comprehension Processes

General Knowledge

Situation Model

Text Representation

Linguistic System

Phonology

Syntax

Morphology

Parser

Meaning and Form Selection

Word

Representation

Word Identification

Lexicon

Meaning

Morphology

Syntax

Orthographic

Units

Phonological

Units

Orthography

Mapping to phonology

Visual Input

16

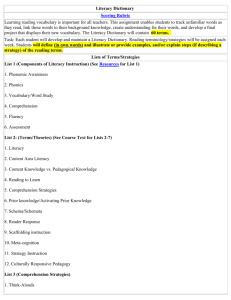

Vocabulary Demands in 6 G1 Basals (Foorman et al., 2004)

Table 4

Representation of Oral and Written Vocabulary in Program (Types)

A B C1 C2 D E

LWV

Levels

2

4

6

8

10

12

13

16

Total

Freq. % Freq. % Freq. % Freq. % Freq. % Freq. %

889 (51.99) 897 (52.55) 891 (52.72) 1101 (48.96) 196 (64.47) 586 (55.44)

609 (35.61) 575 (33.68) 592 (35.03) 785 (34.90) 102 (33.55) 375 (35.48)

104 (6.08) 107 (6.27) 113 (6.69) 197 (8.76)

47

18

(2.75)

(1.05)

35

24

(2.05)

(1.41)

33

16

(1.95)

(.95)

64

28

(2.85)

(1.24)

2

1

1

(.66)

(.33)

(.33)

53

17

8

(5.01)

(1.61)

(.76)

25

9

9

1710

(1.46)

(.53)

(.53)

41

11

17

1707

(2.40)

(.64)

(1.00)

23

14

8

1690

(1.36)

(.83)

(.47)

45

15

14

2249

(2.00)

(.67)

(.62)

2

304

(.66) 10

6

2

1057

(.95)

(.57)

(.19)

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

SF1 53.24 (10.29) 52.64 (10.83) 53.78 (9.72) 51.91 (10.06) 61.42 (9.12) 55.38 (10.10)

Note. LWV = Living Word Vocabulary (Dale & O’Rourke, 1981).

SFI = Standard Frequency Index Zeno et al., 1995).

17

Relation of Frequency in Corpus to

Grade 1 Frequency in Zeno et al. (1995)

18

Some “rare” (G1 Basal) and “not-sorare” (elementary literature) Words

generally greatly hooks hops horned household illness jersey kingdom layer leash least lights

WORD craft due elk exhausted fifth fins flung gathering

LWV Level

6

6

6

6

12

12

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

8

8

8

8

6

6

6

13

Basal f/100 Lit. f/1,000,000

.001684892 4.952

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

11.638

7.429

7.429

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

.001684892

.002813969

.002813969

.002813969

.001684892

.002813969

.002813969

20.800

25.257

11.390

139.904

97.314

5.200

5.200

5.200

10.648

5.695

10.648

23.029

5.448

13.371

16.343

11.886

12.133

19

Representation of Opportunity

Words Across Basals

Total

12

13

16

6

8

10

LWV Level

Number of Programs

1 2 3 4

Total

87 33 9 0 129

14 12 4 2 32

11 2 3 0 16

22 2 5 0 29

3 1 0 1 5

4 1 0 0 5

141 51 21 3 216

20

Opportunity Words in Grade 1 Basals

bronze burrow career cement chops chowder clam clippers clumsy cocoon con ad amuse creak creamy glossary perch gown phrase arch attract create crib granite grief backwards determination gust poetry sped spoiled squad poisonous squire porcupine sturdy blues blur boar boast bony breed device display doe dose driftwood elk haze holly horned illness item jumper potter pox prey prickly pueblo pulp survive swap swoop brilliant celebrated typical coral draws dune elegant fins gerbil tattered gruff thankful hermit ties heron timid vacuum vegetation gracious yourselves handles alas bog brute cam cove flahing foal fro hatching heather hooks hops mantis dialogue mats plankton ticking establish exhausted fangs fearless fig flapped fled foil conservation galley construction garlic contented genius craft gigantic kicks leapt lent listener llama frisky meter furthermore mi gallery mobile mold outdoor packet radar relate relay magnificent rhythm marine rover mercury rum sculpture seller shack shaken shrug overcome slimy sow towering turquoise twinkle walrus wee whaling returns whew whoa wraps wrestle yelp zoom huff lance polar reed reef ribbons rushes scurry si stated stirring thud flora framework minded guinea resist veterinarian promises hangs rhinoceros wag ramp senora hemisphere slanted lulu ping squid stripes taps blasted boa buster chameleon digs chi maze rio sneaking stacks swish tad taro taut twinkling amazon splitting

21

Conclusions on Vocabulary

• Publishers need to provide teachers with cumulative vocabulary lists

• These need to be made available electronically to textbook adopters and should include information on:

– Frequency in text and lesson number

– Separate entry for each definition used

– Derivational forms

– Printed word frequency in other relevant corpora

22

Conclusions on Vocabulary

• Instruction needs to target oral language development from pre-school through high school

• Printed word frequency and age of acquisition are useful tools for guiding selection of lexical entries to be taught

• Assessment of vocabulary for the purpose of Reading First should focus on the link between assessment and instruction

23

Summary and Conclusions

• Programs differ substantially in the composition of their print materials for Grade

1 students

• Length of texts, grammatical complexity, numbers of unique and total words, repetition of words, coverage of important vocabulary

• Differences exist in the decodability of types and tokens

– Generally there is greater decodability for tokens than types,

– most programs show improvements for types later in the year

24

Summary and Conclusions

Programs vary in the approach they take to achieve decodability and in the degree to which materials can be expected to yield accuracy in reading.

- Vary in phonic elements taught

- Vary in opportunity to practice words containing these elements

- Within 6-week blocks, 70% of words are singletons in 4 of the 6 basals

- Vary in reliance on holistically-taught words

25

Implications for fluency

• “…for dysfluent readers, the texts that are read and reread for fluency practice need to have sufficiently high percentages of words within…the word zone fluency curriculum and low percentages of rare words, especialy multisyllabic ones” ( p.

18)

• “Repetition of core words makes science text ideal for fluency practice in the primary grades” (p. 11)

Hiebert (2007)

26

Word Zone Fluency Curriculum

High-Freq Words Phonics/Syllable Morphological

A 300 most freq accuracy rate of 40% in first grade in

Seymour et al., 2003).

B 500 most freq

Short/long vowels

Short & long & rcontrolled vowels

All monosyllabic

Simple, inflected endings

(ed, ing, s, es,’s)

C 1,000 most freq

D 1,000 most freq 2-syllable compound words with at least 1 root from 1,000 most frequent words

Prefixes: un, a

Suffixes: er, est, ly, y (doubling)

E 2,500 most freq

F 5,000 most freq

27

Jabberwocky

(Lewis Carroll, 1872)

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”

And four more stanzas From Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There

Discussion

You know how to pronounce the words in

Jabberwocky; some are real English words.

1. Which ones are real English words?

2. What is the distinction between those that are actual English words and those that aren’t?

3. Do the two paragraphs differ in these distinctions?

29

Alice’s reaction

“It seems very pretty,” she said when she had finished it, but it’s rather hard to understand!” (You see she didn’t like to confess, even to herself, that she couldn’t make it out at all.) “Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas —only I don’t exactly know what they are! However, somebody killed something : that’s clear at any rate —”

30

NAEP 2009 Reading Framework

Characteristics of text difficulty:

• Vocabulary reported out separately

• Subscales for literary & informational text

• Grade-level standards for text type

31

2009 NAEP Framework

Literary Text

● Fiction

● Literary Nonfiction

● Poetry

Informational Text

● Exposition

● Argumentation and Persuasive

Text

● Procedural Text and Documents

Cognitive Targets Distinguished by Text Type

Locate/Recall Integrate/Interpret Critique/Evaluate

32

Achievement Levels for Grade 4 NAEP Reading

Literary Informational Achievement

Level

Advanced G4 students at the Advanced level should be able to :

Interpret figurative language

Make complex inferences

Identify point of view

Evaluate character motivation

Describe thematic connections across literary texts.

G4 students at Advanced level should be able to:

Make complex inferences

Evaluate the coherence of a text

Explain author’s point of view

Compare ideas across texts

Proficient G4 students at the Proficient level should be able to:

Infer character motivation

Interpret mood or tone

Explain theme

Identify similarities across texts

Identify elements of author’s crafts

G4 students at Proficient level should be able to:

Identify author’s implicitly stated purpose

Summarize major ideas

Find evidence in support of an argument

Distinguish between fact and opinion

Draw conclusions

Basic G4 students at the Basic level should be able to:

Locate textually explicit information, such as plot, setting, and character

Make simple inferences

Identify supporting details

Describe character’s motivation

Describe the problem

Identify mood

G4 students at the Basic level should be able to:

Find the topic sentence or main idea

Identify supporting details

Identify author’s explicitly stated purpose

Make simple inferences

33

text type

2009 NAEP Framework

English Mathematics History literary informational or technical, symbolic, diagrams expository, argumentative, persuasive

Science

Informational or technical, diagrams text structure author’s craft plot, setting, characterization, point of view, verse, rhyme sequence, cause and effect, problem and solution, supporting ideas and evidence, graphical features diction, dialogue, symbolism, imagery, irony, figurative language rhetorical structure, examples, logical arguments sequence, cause and effect, problem and solution, author’s perspective supporting ideas and evidence, contrasting viewpoints, graphical features figurative language, rhetorical structure, examples, emotional appeal sequence, cause and effect, problem and solution, supporting ideas and evidence, graphical features rhetorical structure, examples, logical arguments

34

35

What Does Mean to be Proficient?

• W score cutpoints on NAEP and state tests communicate grade-level proficiency or benchmark performance.

• State curriculum standards need to be aligned with benchmarks/proficiency levels.

• Are states’ proficiency levels comparable to

NAEP’s?

36

% Proficient on State vs NAEP Reading 2005

State 4-state 4-NAEP DIFF 8-state 4-NAEP DIFF

ME

MO

WY

53

35

47

35

33

34

-18

- 2

-13

44

33

39

38

31

36

- 6

- 2

- 3

TX

GA

NC

79

87

84

29 -50 83

26 -61 83

29 -55 89

26

25

27

-57

-58

-62

[Porter, 2007] 37

Most state testing systems do not assess college and work readiness

• 26 states require students to pass an exam before they graduate high school.*

• Yet most states have testing systems that do not measure college and work readiness.**

*Source: Center on Education Policy, State High School Exit Exams: States Try Harder, But Gaps Persist, August 2005.

**Source: Achieve Survey/Research, 2006.

38

Graduation exams in 26 states establish the performance “floor”

Figure reads: Alaska has a mandatory exit exam in 2005 and is withholding diplomas from students based on exam performance. Arizona is phasing in a mandatory exit exam and plans to begin withholding diplomas based on this exam in 2006. Connecticut does not have an exit exam, nor is it scheduled to implement one.

Source: Center on Education Policy, based on information collected from state departments of education, July 2005.

39

How challenging are state exit exams?

• Achieve conducted a study of graduation exams in six states to determine how high a bar the tests set for students.

• The results show that these tests tend to measure only 8th, 9th or 10th grade content, rather than the skills students needs to succeed in college and the workplace.

40

State

Florida

Maryland

Massachusetts

New Jersey

Ohio

Texas

The tests Achieve analyzed

Grade

Given Reading Writing Math

10th • •

End of course

10th •

•

•

•

•

•

First

Graduating

Class Facing

Requirement

2003

2009

2003

• 11th

10th •

•

•

• 2003

2007

11th • • • 2004

Source: Achieve, Inc., Do Graduation Tests Measure Up? A Closer Look at State High School Exit Exams, 2004.

41

FL

MD

MA

NJ

OH

TX

Students can pass state English tests with skills ACT expects of 8th & 9th graders

ACT

(11th/12th)

ACT EXPLORE

(8th/9th)

ACT PLAN

(10th)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

Source: Achieve, Inc., Do Graduation Tests Measure Up? A Closer Look at State High School Exit Exams, 2004.

42

% Students Proficient on FCAT

(Level 3 and above)

Grade

3

6

7

4

5

8

9

10

2001

57

53

52

52

47

43

28

37

2006

75

66

67

64

62

46

40

32

Difference

18

13

15

12

15

3

12

-5

43

Is 10

th

Grade FCAT Too Hard?

• The St. Petersburg Times article (4/15/07) concluded correctly that the 10 th Grade

FCAT is harder than the 10 th grade NRT.

• Conclusion based on fact that Level 3

(proficient) performance is 56 th %ile nationally at Gr 7; 80 th %ile at Gr 10

• Or “Why wait until high school to implement world class standards?”

44

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

Absolute level of reading proficiency nationally

Grade level standard on the

FCAT

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

45

5

6

7

8

3

4

Passage Length in Words

Grade FCAT range FCAT average NAEP range NAEP average

100-700

100-900

200-900

200-1000

300-1100

300-1100

350

400

450

500

600

700

200-800

400-1000

9

10

300-1400

300-1700

800

900 500-1500 (12)

% of Passage Types

7

8

9

10

5

6

Grade FCAT Literary

Texts

3

4

60%

50%

50%

50%

40%

40%

30%

30%

FCAT Informational Texts

40%

50%

50%

50%

NAEP Literary

Texts

NAEP Informational Texts

50% 50%

60%

60% 45% 55%

70%

70% 30% (12) 70% (12)

47

FCAT Test Design

• Cognitive Complexity (Webb’s Depth of

Knowledge)

• Content Categories for Reading

- Words & phrases in context

Main idea, plot, & author’s purpose

- Comparison; cause/effect

- Reference & Research – locate, organize, interpret, synthesize, & evaluate information

48

To Make Proficiency Standards

Meaningful and Fair

• Agree on target for proficiency (e.g., college readiness)

• Align elementary, middle, and high school targets

• Align curriculum standards

• Evaluate dimensionality of tests and prepare instruction accordingly

• Equate state tests with NAEP to guarantee comparability and equity

49

From Barbara Tuckman’s The Zimmerman Telegram…

The first message of the morning watch plopped out of the pneumatic tube into a wire basket with no more premonitory rattle than usual. The duty officer at the

British Navel Intelligence twisted open the cartridge and examined the German wireless intercept it contained without noting anything of unusual significance. When a glance showed him that the message was in non-navel code, he sent it in to the Political Section in the inner room and thought no more about it. The date was

January 17, 1917, past the halfway mark of a war that had already ground through thirty months of reckless carnage and no gain.

50

What Makes This Text Difficult?

• Consider the text type and structure

• Consider prior knowledge

• Consider the vocabulary

• Consider the discourse features—linguistic markers for coherence, coreference, deixis

• Other factors?

51

Instructional Considerations

• Text Type/Structure

– persuasive text

• anti-war sentiment, “thirty months of reckless carnage and no gain”

• indictment of war bureaucracy

– narrative structure

– historical non-fiction

• Prior Knowledge

– World War I

• text references: war, 1917, British, German, duty officer

– early 20 th century communications

• text references: telegram, pneumatic tube, wire basket, wireless intercept

– Zimmerman telegram

• text references: German wireless, non-naval code

52

53

Instructional Considerations

(continued)

• Vocabulary

– academic language

• examined, significance, “ground through”

– generative words

• premonitory, carnage, intercept

– Tier 3 vocabulary (military domain)

• “morning watch,” non-naval code, German wireless, pneumatic tube

• Linguistic Markers (Coherence Relations)

– pronouns

• duty officer = he, him

– co-references

• German wireless intercept = the message

– deixis

• “in the inner room”

– chronology

• “When a glance showed him that the message was in non-navel code,…”

54

Instructional Delivery

• Model strategies (activating background knowledge, questioning, searching for information, summarizing, organizing graphically, identifying story structure (e.g.,

Guthrie et al., 2004; Brown, Pressley et al., 1996)

• Keep the focus on the meaning of the text through high quality discussion.

• Model “thinking like an historian” (e.g., sourcing) to provide a purpose for reading

(Biancarosa & Snow, 2004).

55

Measuring Text Difficulty

• Teacher judgment

• Readability: Tuchman passage ranges from

8.4 on Dale-Chall to 13.3 on the Flesch-

Kincaid & Fry; 13.5 on Lexiles.

• Latent semantic analysis

• Natural language processing (e.g.,

McNamara, 2001)

• Text equating to control passage difficulty

56

Limitations of readability

• Circular use

• Capture surface features only

• Measurement error on specialized text

- Primary grade text

- Poetry

- Technical documents (e.g., train schedules; tax forms)

57

How Do We Assess Academic

Literacy?

58

Discussion of Academic Literacy

Assessment

• What are the important knowledge and skills to assess in K-3?

• What are the important knowledge and skills to assess in 4-12?

• What kind of text should be used?

• What kind of outcome measures should be used?

59

Converging Evidence

Valid and reliable predictors of risk for reading difficulty are:

Print concepts (early K)

Letter name knowledge (early K)

Phonological awareness and letter sounds (K-1)

Rapid naming of letters (end of K to early G1)

Word recognition (G1 and beyond)

Vocabulary

Assessing written language

• Use various formats to assess:

--multiple choice

--cloze

--maze

--question/answer

--constructed response

--retelling

--sentence verification

• Report achievement in language proficiency levels to chart ELLs progress (Francis, 2008)

61

New PK-12 Florida Reading

Assessment System

• Instructionally useful; free to FL schools in 2009-2010

• Includes vocabulary and comprehension

• Computer administered in grades 3-12

• Screening, progress monitoring, & diagnostic assessments; data available in the Progress Monitoring & Reporting

Network (PMRN)

• Screen is empirically linked to the Florida Comprehensive

Assessment Test (FCAT) or outcome measure

• Targeted diagnostic inventories administered to students not meeting expectations are linked to Florida standards and provide information for guiding instruction

• Reading comprehension & oral reading fluency passages are equated for difficulty to allow for accurate progress monitoring

• Instructional level passages provided

62

New Reading Assessments

• PK: print knowledge, phonological awareness, vocabulary, math (linked to K screening)

• K-2: phonemic awareness, letter knowledge, decoding, encoding, fluency, vocabulary, listening or reading comp.

• 3-12: adaptive complex & low level reading comp., fluency, word analysis, skill assessment

• K-12: Informal reading inventories

• Lexile scores in grades 3-12 allow matching students to text and access to online libraries

• Identifies risk of reading difficulties and reading disabilities

63

New Reading Assessments

64

Thank you!

bfoorman@fcrr.org

www.fcrr.org

65

References

• Biancarosa, G., & Snow, C.E. (2004). Reading next —A vision for action and research in middle and high school literacy: A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York . Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent

Education.

• Brown, R., Pressley, M., Van Meter, P., & Schuder, T. (1996). A quasi-experimental validation of transactional strategies instruction with low-achieving second grade readers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88 ,

18-37.

• Foorman, B.R., Francis, D.J., Davidson, K., Harm, M., & Griffin, J. (2004). Variability in text features in six grade 1 basal reading programs. Scientific Studies in Reading, 8 (2), 167-197.

• Guthrie, J.T., Wigfield, A., Barbosa, P., Perencevich, K.C., Tabada, A., Davis, M.H., Scafiddi, N.T., & Tonks,

S. (2004). Increasing reading comprehension and engagement through Concept-Oriented Reading

Instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology , 96 (3 ) , 403-423.

• Hiebert, E.H. (2007). A fluency curriculum and the texts that support it. In P. Schwanenflugel & M. Kuhn

(Eds.), Creating a literacy curriculum: Fluency instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

• National Assessment Governing Board (in press). 2009 NAEP Reading Framework . Washington, D.C.:

Author. Retrieved March 26, 2007 from http://www.naepreading.org/ .

• National Research Council (1998). Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children. Committee on the

Prevention of Reading Difficulties in Young Children, Commission on Behavioral and Social Science and Education . In C.E. Snow, M.S. Burns, and P. Griffin (Eds.). Washington, DC: Nat’l Academy Press

• Perfetti, C.A. (1991). Representation and awareness in the acquisition of reading competence. In L. Rieben &

C. Perfetti (Eds.), Learning to read: basic research and its implications (pp. 33-44). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

• Porter, A. (2007). NCLB lessons learned: Implications for reauthorization. In A. Gamoran (Ed.), Will “No Child

Left Behind “ help close the poverty gap?

Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

• RAND Reading Study Group (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward a R&D program in reading comprehension.

Arlington, VA: RAND.

• Snow, E., Porche, M., Tabors, P., & Harris, S. (2007). Is literary enough?

Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

• Snowling, M.J., & Hulme, C. (2005). The science of reading: A handbook . NY: Blackwell.

• Sweet, A.P., & Snow, C.E. (2003). Rethinking reading comprehension . NY: The Guilford Press.

• Zeno, S.M., Ivens, S.H., Millard, R.T., Duvvuri, R. (1995). The educator’s word frequency guide. NY:

Touchstone Applied Science Associates, Inc.

66