Guidelines for Successful Partnerships between Public Sector

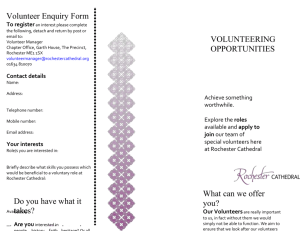

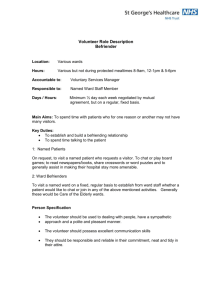

advertisement