cardiomyopathies

advertisement

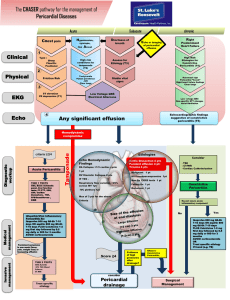

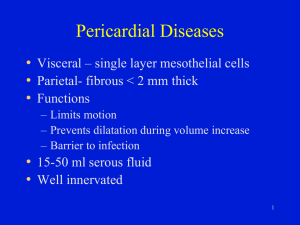

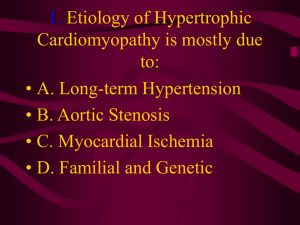

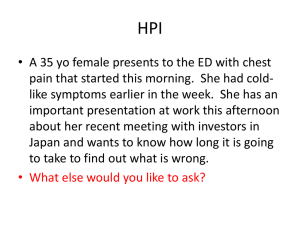

Myocardial and Pericardial Disease J.B Handler, M.D. Physician Assistant Program University of New England 1 Abbreviations LV/RV- left ventricle/right ventricle EF- ejection fraction IVCD-intraventricular conduction delay MR- mitral regurgitation LVOT- left ventricular outflow tract SAM- systolic anterior motion IVS- interventricular septum DHP- dihydropyridine Rx- treatment Bx- biopsy FH- family history HJR- hepato-jugular reflux MVO2- myocardial oxygen consumption OP- out patient Nl- normal LSB- left sternal border PND- paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea JVD- jugular venous distention RA- rheumatoid arthritis SLE- systemic lupus erythematosis Dx- diagnosis ARB’s- angiotensin receptor blockers ICD- inplantable cardioverterdefibrillator HF- heart failure HF=CHF- congestive heart failure CHD- coronary heart disease ASH- asymmetric septal 2 hypertrophy Dilated Cardiomyopathy Primary: idiopathic - unknown cause Secondary: – – – – Toxic - alcohol, adriamycin, etc. Post-partum Post infectious - myocarditis Endocrine: hypothyroidism, pheochromocytoma, acromegaly and hyperthyroidism – “Ischemic Cardiomyopathy”- avoid this terminology 3 Clinical Features Patients present with signs and symptoms of HF which usually develops slowly. Left or biventricular failure Left sided: DOE, orthopnea, PND, weakness, fatigue, peripheral edema, etc. Right sided: unexplained weight gain, peripheral edema, abdominal fullness (hepatomegaly, ascites). 4 Dilated Cardiomyopathy Physical Exam Cardiomegaly (PMI displaced laterally), low pulse amplitude (pulsus alternans when severe), often with BP, pulmonary congestion, crackles, S3 gallop, MR murmur. Elevated JVP, hepatomegaly, HJR, pitting edema, TR murmur. 6 Diagnostic Studies CxR: Cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion, pleural effusions. Echocardiography/Doppler: LV/RV dilation, global LV dysfunction with reduced EF; Mitral regurgitation common. EKG- NSST-T changes, IVCD (wide QRS), PVC’s. Cardiac Cath: only when necessary to exclude alternative diagnosis i.e CHD; documents low EF, global dysfunction, high filling pressures. 7 Treatment Management for HF: Afterload reduction: ACEI or alternatives (ARB’s) Preload reduction: Diuretics, nitrates Beta Blockers Spironlolactone Digoxin ICD’s if indicated, +/- antiarrhythmics Anticoagulation unless contraindicated 8 Clinical Course and Prognosis Dependent on length of Sx and functional class. If onset recent, some recovery of ventricular function can occur. Class IV patients: 50% one year mortality Unpredictable course, often progressive Only meds that may improve survival are ACEI (or ARB’s), ß-Blockers and Spironolactone. Cardiac Transplantation: >70% 5yr. survival 9 Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Genetically transmitted in >50% of cases. Autosomal dominant with high penetrance. – Must perform echocardiography on all siblings and offspring of a patient with HCM. Remaining cases occur spontaneously; de novo gene mutations common. Genetic counseling is essential. 10 Pathophysiology of HCM Marked increase in left ventricular mass, especially the septum - marked hypertrophy; remaining LV segments hypertrophied to a lesser degree; septal/posterior wall thickness > 1.5/1 “ASH”. Hypertrophy is unrelated to pressure overload; often present at birth, progessively worsens during childhood. LV cavity small, systolic function normal or hyperdynamic early on. Diastolic dysfunction common Obstructive and non-obstructive forms 11 HCM When present LVOT obstruction is dynamic and varies with activity/rest, and LV volume. – Obstruction: MV moves abnormally towards the IVS, obstructing the LVOT. Pathology: myocardial fiber hypertrophy and disarray, primarily in IVS. Mitral valve often thickened and moves abnormally as noted above, well seen on echocardiogram. 13 Clinical Manifestations Often asymptomatic in childhood; may be detected via ultrasound in the offspring of patients with known disease. Symptoms: dyspnea, chest pain and syncope are most common. In some, sudden death may be presenting symptom. One of few causes of sudden death in young athletes. Sudden death often occurs during strenuous activity. Arrhythmias are common: ventricular and supraventricular; Afib may lead to sudden decompensation and is a bad prognostic sign. 14 Physical Exam Pulse brisk, often. with bisferiens carotid pulse. Double or triple apical impulse due to atrial filling wave and early and late systolic impulses. Loud S4 and S3 gallops. Loud harsh aortic outflow murmur (creshendodecreshendo) best heard along left sternal border with characteristic features (see below); MR common. 15 Effects of Maneuvers on Murmur Most cardiac murmurs are increased by squatting and decreased by standing or with valsalva. The murmur of HCM is increased with standing & valsalva and decreased with squatting. This is the opposite of how the murmur of aortic stenosis acts. Other things that the murmur include hypovolemia, tachycardia or increases in cardiac contractility (inotropes, exercise). 16 Diagnostic Studies ECG- LVH with secondary ST-T changes common. Septal Q waves may mimic MI. Echocardiogram/Doppler diagnostic CxR often unimpressive. 17 HCM: Management Essential to minimize strenuous physical exertion. Beta Blockers: slow HR, ’s diastolic filling time, ’s MVO2 with additional anti-arrhythmic effects: – Angina, dyspnea and presyncope may all improve. Beta blockers also may prevent the increase in outflow obstruction that occurs with exercise. Large doses of ß-blockers well tolerated. 18 HCM: Management Calcium channel antagonists (verapamil)- used with (or as an alternative) to ß-blockers. – Only time when verapamil added to ß-blocker Improve diastolic filling and compliance via negative inotropic and chronotropic effects decrease LVEDP. – Symptomatic improvement and improved exercise tolerance in over 2/3 of treated patients. Verapamil in high dosage is well tolerated. Don’t use DHP Ca blockers can worsen Sx. 19 HCM: Interventional Therapy Surgery or procedures to reduce septal muscle: myomectomy, alcohol ablation: severe obstruction or symptoms. Dual chamber pacemaker may improve septal motion and decrease progression of obstruction if severe. ICD: high risk patients (documented v-tach, aborted sudden death) or FH of sudden death. 20 Restrictive and Infiltrative Cardiomyopathies Hallmark: Abnormal diastolic function. Ventricular walls excessively rigid and impede diastolic filling; systolic function may be normal or reduced. Pathophysiology resembles constrictive pericarditis. Least commonly seen of the cardiomyopathies. 21 Restrictive Cardiomyopathy: Findings Jugular venous distention S3 and/or S4 Inspiratory increase in venous pressure (Kussmaul’s sign) Findings of Rt. Heart Failure may predominate i.e. edema, hepatomegaly. Symptoms include dyspnea, exercise intolerance and fatigue. 22 Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Echo-doppler findings include: LV wall thickening; decreased diastolic relaxation. Systolic function-preserved or diminished Disease process may have characteristic echo findings i.e. amyloidosis. Tricuspid and mitral regurgitation are common. 23 Natural History Relentless symptomatic progression; >90% dead at 10 years. No specific treatment other than symptomatic. Calcium Channel Antagonists may improve diastolic function in selected individuals. 24 Etiologies Amyloidosis Hemochromatosis Fabry Disease Gaucher Disease Endomyocardial Fibrosis-Loeffler Endocarditishypereosinofilia syndrome 25 Myocarditis A primary inflammatory process of the myocardium, most often caused by an infectious agent. Unrecognized myocarditis may be the initial event culminating in an “idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy”. 26 Infectious Myocarditis Viral - most common Bacterial- numerous Fungal-aspergillosis, candidiasis, etc. Parasitic – Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas’) Rickettsial Spirochetal 27 Viral Myocarditis and Pericarditis Coxsackievirus (B>A) CMV Echovirus Adenovirus HIV Influenza Infectious mononucleosis Rubella, Rubeola 28 Clinical Manifestations May be asymptomatic Prodromal viral syndrome followed symptoms of myopericarditis. – Chest pain, fatigue, dyspnea, palpitations are common initial symptoms. Often progresses to HF. Initial presentation may be HF. Exam : Tachycardia, elevated temp, muffled heart sounds; signs of HF in severe cases. 29 ECG: sinus tachycardia with NSST-T changes. Other findings: ST elevation consistent with pericarditis may occur. CXR: heart size normal or enlarged; pulmonary congestion may be present. Echo-doppler: some degree of LV dysfunction (regional or global); LV size normal or increased, wall thickness usually normal. Thrombus may be present with severe dysfunction. 30 Diagnosis Difficult to confirm acute diagnosis Acute and convalescent viral titers; presence of virus in other tissues. Troponin levels or CK-MB isoenzyme are often normal but may be mildly elevated. Endomyocardial biopsy may isolate virus (rare), or show characteristic pathology of myositisinflammatory infiltrate. 31 Treatment Supportive Rx Rx HF if present. Important to limit activity. Specific anti microbial Rx if an infecting agent is identified (if treatable). Biopsy guided immunosuppressive and corticosteroid Rx is available under investigative protocols - no proven benefit. Avoid NSAIDs: may increase myocardial damage. Prognosis variable: Ranges from death to varying degrees of recovery 32 Acute Pericarditis A syndrome due to inflammation of the pericardium characterized by chest pain, a pericardial friction rub, and serial ECG abnormalities. 33 Causes of Pericarditis Viral most common; same spectrum of viruses as seen with myocarditis- Coxsackie most common. Idiopathic (non specific) Tuberculosis Acute bacterial infections Fungal Uremia-untreated or with dialysis. Radiation Autoimmune-RA, SLE, scleroderma, PAN 34 Drug induced: hydralazine, procainamide, isoniazid, penicillin. Trauma: Chest trauma; post thoracotomy; pacemaker insertion; post cath., PTCA. Early post MI Delayed post myocardial-pericardial injury syndromes: late post MI (Dressler’s syndrome) or post heart surgery (postpericardotomy syndrome). Neoplastic disease- lung cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, Hodgkins disease, leukemia. 35 Clinical Manifestations Chest pain-frequent; quality and location variable; retrosternal and often left sided. Pain is intenseaggravated by lying supine, with inspiration, coughing, swallowing, laughing; improved sitting up, leaning forward, shallow inspiration. Chest pain may be felt with each heart beat. On occasion pain may be identical in quality to the pain of myocardial infarction. Dyspnea may be related to shallow breathing from inspiratory chest pain. 36 Pericarditis: Physical Exam Pericardial Friction Rub-pathognomonicscratching, grating, high pitched sound due to friction between the pericardium and epicardium. 3 components related to cardiac motion: presystole (atrial contraction), ventricular systole (loudest component), and early diastole. Usually hear 2 components (S/D). Rub is evanescent; best heard with diaphragm at LLSB; best heard with patient sitting, leaning forward in full expiration. 37 Diagnostic Findings ECG: Changes begin within hours of the onset of pain; several stages. ECG abnormalities reflect inflammation involving the pericardium and epicardium. Initially there is diffuse ST segment elevation in all leads except aVR and V1. Later ECG’s show normalization of ST elevation followed by T wave flattening and T wave inversion. 38 ECG Pericarditis Diagnostic Findings Cont.... Early repolarization, a normal variant often seen in young healthy individuals (male> female) may mimic the ECG findings seen in the acute phase of pericarditis, but less ST & seen in fewer leads. Echo-doppler: nl LV size and function rules out myocarditis; a small pericardial effusion may be seen; this rarely progresses with viral pericarditis, but a repeat study to document resolution is indicated. CXR: usually normal; occasionally cardiomegaly due to a pericardial effusion is seen. 40 Management Determine etiology where possible. Bed rest until pain and fever resolved. Most patients Rx’d as OP. Hospitalization may be indicated if MI suspected or if large effusion present. Pain rapidly responds to NSAIDs: Ibuprofen, high dose ASA, etc; steroids rarely necessary. Oral anticoagulants should be avoided in patients with pericarditis. Symptoms usually resolve in 2-4 weeks. 41 Pericardial Effusion Without Cardiac Compression Can occur with all forms of pericarditis Symptoms (if present) include chest pressure, dyspnea, hiccups, nausea, abd. fullness, cough. CxR-mild cardiomegaly if >250 cc. fluid. ECG: NSST-T changes; decreased QRS voltage. Echo: Best technique to Dx. and follow; useful to determine presence of tamponade. Management-depends on the presence or absence of hemodynamic compromise, and the underlying disease process. 42 Pericardial Effusion With Compression: Tamponade Increasing pericardial fluid raises intrapericardial pressure resulting in compression of the heart. There is progressive limitation of ventricular diastolic filling leading to reduction of stroke volume and cardiac output. Fatal if not recognized and aggressively treated. 43 Cardiac Tamponade Hemodynamics - marked elevation and equilibration of LV and RV diastolic pressures; LA and RA pressures elevated. Marked decrease in CO. RA and RV collapse is seen on echo. Beck’s triad: decline in arterial pressure, elevation of systemic venous pressure, quiet heart. Cardiac output is extremely volume sensitive. 44 Pulsus Paradoxus Normally during inspiration-increase venous return, slight increase in RV volume, IVS displaced from rt to lt- slight decrease in LV volume. RV output increases, LV output slightly falls- results in minimal (2-3%) drop in systolic BP (2-4mm). Pulsus paradoxus is a marked exaggeration of this process; intrapericardial pressure is markedly increased-RV and LV volumes are already diminished; inspiration results in a marked in LV volume resulting in a systolic BP drop > 10mm. 45 Cardiac Tamponade CxR and ECG are ancillary tests. Echocardiogram is often diagnostic. Pericardiocentesis: may be life saving; IV fluids given to increase preload; should be done with Rt Ht Cath to optimize hemodynamics; subxiphoid approach with flouroscopic guidance is successful in 95%; fluid is cultured and sent for cytology and chemistry analysis. Surgery: Pericardectomy and pericardotomy are necessary in 25% for recurrent tamponade. 46