Cardiology Clincopathologic Case

advertisement

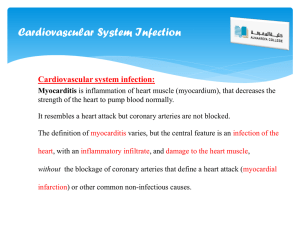

Clinical Pathologic Conference Division of Cardiology Andrew Bolin May 11th, 2007 The Case Chief Complaint: Irregular Heart Beat, Dyspnea and Fatigue. HPI: A 74 year old white female with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation for 7 years is referred to the cardiology clinic. The patient had intermittent paroxysms of atrial fibrillation while taking flecainide for 5 years. In the month prior to referral, she was hospitalized twice for rapid atrial fibrillation. The Case Before the first hospitalization, the patient reported symptoms of: paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea and dyspnea on exertion. During the first hospitalization, flecainide was discontinued and warfarin and metoprolol were started. She ruled out for an acute myocardial infarction and a dipyridamole thallium study did not demonstrate ischemia. An echocardiogram revealed normal left ventricular function and a mildly enlarged left atrium. The Case Two weeks prior to her second hospitalization, the patient experienced the sudden onset of: fatigue, decreased endurance, irregular heart beat, constant chest pressure and profound dyspnea on exertion. Prior to this illness, the patient could ambulate for thirty minutes without fatigue or dyspnea. On the day of consultation she experienced dyspnea on walking 20 yards. Review of Symptoms: Positive for: 10 pound weight gain, diffuse chronic myalgias, and anxiety Past Medical History Hypertension for 11 years Breast Cancer: underwent left mastectomy and chemotherapy 14 years before. No radiation therapy. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections Social History Married to retired Methodist minister Two adult children No alcohol, tobacco or illicit drugs No unusual exposures Family History Mother died of congestive heart failure at age 79 Sister breast cancer Sister “bone cancer” Medications Metoprolol 25 mg BID Allergies: Macrodantin Coumadin Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg Daily Celexa 10 mg Daily Aspirin 81 mg Daily Bactrim DS three days per week Physical Exam Blood Pressure 148/78 (in both arms) Pulse 90 Respirations 18 Neck: normal jugular venous pressure, symmetric brisk carotid upstrokes without bruits, no lymphadenopathy Lungs: clear to auscultation, dullness to percussion in right base Physical Exam Cardiac: normal point of maximal impulse, normal S1, physiologically split S2, no murmurs, rubs or gallops, strong and symmetric peripheral pulses Benign Abdominal Exam Extremities: no clubbing, cyanosis or edema Musculoskeletal: tenderness to palpation in trapezius and shoulder girdle bilaterally Studies Electrocardiogram: atrial fibrillation, incomplete right bundle branch block and nonspecific ST-T abnormalities Chest X-ray: possible right pleural effusion Transesophageal Echocardiogram: unusual thickening of left atrial walls, small pericardial effusion Studies Chest CT: pericardial effusion and bilateral pleural effusions, biapical pleuroparenchymal scarring Cardiac MRI: atrium unremarkable Labs: CBC, E-group, BUN, Creatinine, TSH, Troponin and CK were all within normal limits. Right Thoracentesis Consistent with Transudative Effusion WBC 485, Lymphocytes 89% Flow Cytometry: Consistent with a Reactive Effusion. Cytology: No Malignant Cells Case Summary Elderly White Female with A-fib Progressive Symptoms of CHF Over Weeks Without Echocardiographic Evidence of LV Dysfunction Transudative Lymphocytic Bilateral Pleural Effusions Biapical Pleuroparenchymal Scarring Pericardial Effusion Without Evidence of Tamponade Incomplete Right Bundle Branch Block Abnormal Left Atrial Walls Case Summary The Patient Has a Pathologic Process Involving the Pericardium and Myocardium that is Not Related to Valvular or Ischemic Disease. Additionally, Noted is an Echocardiogram Demonstrating Highly Abnormal Left Atrial Walls. Causes of Lymphocytic Pleural Effusions CHF (Only Transudate) Neoplasm Fungal Infection TB Sarcoidosis Rheumatoid Arthritis Hepatic Hydrothorax Yellow Nail Syndrome Chylothorax Causes of Left Atrial Enlargement Valvular Disease Myocardial Infarction Obstructive Cardiomyopathy Hypertension Infiltrative Cardiomyopathy Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy Primary or Metastatic Tumors Differential Diagnosis for Pericardial Effusion Infectious Malignant Autoimmune Cardiomyopathy Drug Induced Cardiac Constrictive Pericarditis Radiation Trauma Metabolic: Hypothyroidism Uremia OvarianHyperstimulationSyndrome Pericardial Effusion All Causes of Pericardial Effusion Can Also Cause Pleural Effusions. All Causes of Pericardial Disease Can Also Include the Myocardium to Varying Degrees. Termed Myopericarditis or Perimyocarditis. Infectious Pericardial Effusion Viral Pyogenic/Bacterial Fungal Parasitic Tuberculous Any Infectious Agent Can Affect the Pericardium Viral Pericarditis Most Common Infectious Pericarditis Usually Cause Acute Pericarditis with: Fever, Rub, Typical ECG Changes, Leukocytosis, 3:1 Male to Female Ratio, Predominately in Young Adults Usually Self Limited Resolving Within 2 Weeks Preceded by Upper Respiratory or GI Illness by 1-3 Weeks 50% Have Recurrence Within 8 Months Common Viruses: Enteroviruses, Coxsackie A&B, Adenovirus, Rhinovirus, Echovirus type 8, and Influenza Diagnosis of Exclusion Pyogenic/Bacterial Pericarditis Fulminant Course Symptoms Arise Over a Few Days and Usually Lead to Tamponade and Sepsis Commonly Pneumococus, Staph, Strep Typically Associated with High Fever (Virtually All Cases), Toxicity, Tachycardia, Rub Maybe More Insidious Course in the Elderly Usually Require Systemic Antibiotics and Pericardial Drainage With Exploration In the Antibiotic Era Usually Associated with Dialysis, Thoracic Surgery and Chemotherapy. Fungal Pericarditis Usually Occurs in Immunocompromised Histoplasma: Usually Young Males in Endemic Areas, Often Benign Course Remitting Spontaneously, May Have Mediastinal Lymphadnopathy and Pleural Effusions Coccidiomycosis: Usually in Patients with Widely Disseminated Infection Candida & Aspergillus: Opportunistic, Necrotizing and Leading to Thrombosis Parasitic Pericarditis Clinical Course Resembles that of Pyogenic Pericarditis Residents or Travelers to Endemic Areas Usually Have an Identifiable Primary Source i.e. Liver or Lung Eosinophillia Primary Tumors 75% Benign, 50% of Benign Tumors Are Myxomas 25% Malignant 95% of Malignant Tumors Are Sarcomas 5% of Malignant Tumors Are Lymphomas Symptoms Related to Location and Size The Pathology of the Tumor Can Be Speculated by Appearance on Imaging and Anatomic Location Myxomas Occur in 3rd-6th Decades Female Predominance 60-70% 80% Found in the Left Atrium Presentation: Obstruction of Mitral or Tricuspid Valve 67% (Occasionally Positional), Embolization 29%, 15% of Cases Have Audible Tumor Plop Constitutional Symptoms: Fever, Fatigue, Weight Loss, Myalgias, and Arthralgias Not Commonly Associated With Pericardial Effusion Myxomas Echo Demonstrates Endocardial Mass, Rarely May Be Intramural Treatment is Surgical Resection, Though Myxoma May Recur 1-5% 10% May Be Familial Benign Papillary Fibroelastomas 2nd Most Common Benign Tumor Predominantly Affect Valves, Account for 75% of Valvular Tumors Often Asymptomatic, But May Present with Dyspnea, Embolization, or Chest Pain Visible By Echo as Mobile Endocardial Mass Other Benign Cardiac Tumors All Are Rare Rhabdomyomas: Most Present in Childhood Fibromas: Most Present in Childhood Hemangiomas: Have Characteristic Findings on Imaging Lipomas: Have Characteristic Findings on Imaging Teratomas: Have Characteristic Findings on Imaging, Most Present in Childhood Malignant Sarcomas Angiosarcomas: Most “Common” Malignant Primary Cardiac Tumor Men:Women 3:1, 65-90% Have Metastases at Presentation 80% Occur In the Right Atrium (Other Sarcomas Are Usually in the Left Atrium) Malignant Sarcomas Rhabdomyosarcoma: 2nd Most “Common” Malignant Primary Cardiac Tumor Can Occur at Any Age Most Have Aggressive Features Seen on Imaging (Invasion of Local Structures) Primary Cardiac Lymphomas By Far Most Commonly Occur in the Right Atrium More Common in AIDS and Immunocompromised Patients Most Are Fatal Shortly After Diagnosis Metastatic Tumors 20 Times More Common than Primary Tumors Lung, Breast, Leukemia, Lymphoma, Melanoma, Kaposi’s Sarcoma Presenting Symptoms Based on Location of Tumor, Usually Causes Pericardial Effusion If the Patient Is Symptomatic the Tumor Is Virtually Always Visible on Echo, CT or MRI Most Patients Have Mediastinal Lymphadnopathy Most Have Aggressive Features Seen on Imaging (Invasion of Local Structures) Autoimmune Pericardial Effusion Rheumatoid Arthritis SLE Scleroderma Rheumatic Fever Wegener’s Granulomatosis Ankylosing Spondylitis Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cardiomyopathies Ischemic Dilated Hypertrophic Valvular Hypertensive Restrictive or Infiltrative Inflammatory Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Excessively Rigid Ventricular Walls Cause Diastolic Dysfunction Systolic Function Is Not Impaired Commonly Present with Dyspnea, Fatigue and Chest Pain Commonly Associated with A-Fib Difficult to Distinguish Clinically from Constrictive Pericarditis Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Storage Diseases Infiltrative Endomyocardial Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Inherited Storage Disorders Hemochromatosis: Deposition of Iron in Liver, Pancreas, Gonads and Myocardium Fabry: Intracellular Accumulation of Glycosphingolipids in the Skin, Kidneys and Myocardium Gaucher: Accumulation of Cerebrosides in the Spleen, Liver, Bone Marrow, Lymph Nodes, Brain and Myocardium Glycogen Storage Diseases: Survival to Adulthood Uncommon Except in Type III, Where Infiltration of the Myocardium is Usually Not Clinically Relevant Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Infiltrative Disorders Amyloid Sarcoid Carcinoid Heart Disease: Serotonin Producing Tumor Causing Cutaneous Flushing, Diarrhea, Bronchoconstriction and Right Sided Endocardial Plaques Composed of Fibrous Tissue Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Endocardial Fibrotic Diseases Endomyocardial Disease (Africa, Eosinophilia) Loffler Endocarditis (Eosinophilia) Endomyocardial Fibrosis (Africa) Myocarditis Primary Lymphocytic Acute Rheumatic Fever Eosinophilic Lyme Chagas HIV Drugs Radiation Giant Cell Myocarditis Inflammation of the Myocardium Associated with Injury to Myocytes Presents as an Acute Illness, Often Congestive Heart Failure, Chest Pain and Fatigue Moderate Elevation of Cardiac Biomarkers, Nonspecific ST-T Changes, Arrhythmias, Nonspecific Echo Diagnosis by Endomyocardial Biopsy Myocarditis Primary or Acute Myocarditis Associated with Viral Infection (20 Viruses). Most Commonly Enteroviruses (Coxsackie). Viral Etiology Suggested by Antecedent Upper Respiratory or GI Illness. Acute Viral Myocarditis is Associated with Lymphocytic Infiltrate Inflammatory Myocarditis Lymphocytic Myocarditis: Most Will Improve Over 1-6 Months, a Minority Will Fail to Clear a Cardiotropic Virus or Develop Persistent Inflammation That Leads to Chronic Cardiomyopathy, Heart Block or Ventricular Arrhythmias. Myocarditis Treatment Trial: Prospective Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Prednisone and Cyclosporine or Azathioprine for the Treatment of Biopsy Proven Lymphocytic Myocarditis in Acute CHF. There Was No Benefit from Immunosuppression. Immune Modulation for Acute Cardiomyopathy: Evaluated the Role of IVIG and Found no Benefit. May Lead to Dilated Cardiomyopathy Inflammatory Myocarditis Acute Rheumatic Fever: Pancarditis Occurring in 3% of Untreated Streptococal A Pharyngeal Infections Hypersensitivity Myocarditis (Drug Induced): Tricyclics, Penicillins, Antipsychotics, Present with Rash & Fever Eosinophilic Myocarditis: Occurs in Conjunction with: Hypereosinophilic Syndrome, Churg-Strauss Syndrome & Loffler’s Endomyocardial Fibrosis. Peripheral Eosinophilia Lyme Myocarditis: Borrelia burgdorferi, Often Develop Heart Block or Arrhythmias, Chagas Cardiomyopathy: Trypanosoma cruzi (Protozoan), Endemic to Central & South America HIV Myocarditis Drug Induced Pericardial Effusion Procainamide Hydralazine Phenytoin Isoniazide Minoxidil Methysergide\ ergot derivative Phenylbutazone/ NSAID Anticoagulants Cromolyn Sodium Dantrolene Thrombotics Penicillin Doxorubicin/ Adriamycin Cytoxan/ Cyclophosphamide Cardiac Pericardial Effusions Myocardial Infarction Postmyocardial Infarction “Dressler’s Syndrome” Trauma Aortic Dissection with Hemorrhage into Pericardial Space Postpericardiotomy Constrictive Pericarditis No Pericardial Thickening Was Noted on Imaging Few Case Reports of Constriction Without Pericardial Thickening Would Not Account for Abnormal Left Atrium Seen on Echo Possible Etiologies for This Case Tuberculous Pericarditis Cardiac Sarcoidosis Cardiac Amyloidosis Giant Cell Myocarditis Tuberculous Pericarditis 4-10% of All Acute Pericarditis is Caused by TB (Reported up to 80% in Some 3rd World Countries) 1-4% of Patients with TB Have Pericardial Involvement Etiology of 20% of Constrictive Pericarditis Cases 93% of all Pericardial Effusions in HIV Patients Four Pathologic Stages of TB Pericarditis I-Dry: Fibrin Deposition & Granulomatous Reaction. Usually Clinically Silent II-Effusive: Serous Fluid Accumulation Caused by Hypersensitivity to Tuberculoprotein and Impaired Resorption III- Absorptive: Effusion Resolves and Fibrous Tissue Replaces Granulomas, Pericardium Thickens IV-Constrictive: Parietal Pericardial Calcification Presentation of Tuberculous Pericarditis Dyspnea 45-90% Chest Pain 40-75% Orthopnea 20-65% Distant Heart Sounds 25-55% Rub 30-85% Cough 50-95% Fever 80-100% Presentation of Tuberculous Pericarditis 50% of Patient Have Slowly Progressive Insidious Presentation 95% Have Cardiomegally, 30% Have Active Pulmonary TB, 39-71% Have Pleural Effusions L>R. Bilateral Pleural Effusions More Common than Rub. Tuberculous Pericarditis “Because of the variable and nonspecific features of TB pericarditis, establishing the diagnosis on clinical grounds alone is impossible.” D.H. Spodick Diagnosis by Pericardial Fluid or Biopsy: Positive AFB Smear, Culture, Caseating Granulomas, TB DNA PCR Treatment Tuberculous Pericarditis Antibiotics: Isoniazid, Rifampin, Pyrazinamide, Ethambutol Corticosteroids: Reduces Mortality and Need for Subsequent Pericardiocentisis Cardiac Sarcoidosis Causes Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Clinically Relevant in 5%, 25% Incidentally Noted at Autopsy 69% of Clinically Relevant Cardiac Sarcoidosis Patients Have No Other Manifestations of the Disease at Presentation Presentation: Complete Heart Block (Be Suspicious in Young Patients With Complete Heart Block), Ventricular Arrhythmia, Congestive Heart Failure Systolic or Diastolic Dysfunction Cardiac Sarcoidosis Echo Usually Reveals Hyperechogenic Left Ventricular Walls, May Develop Ventricular Aneurysm From Myocardial Scar Tissue Diagnosis Based on Clinical Suspicion in a Patient with Known Sarcoid or by Endomyocardial Biopsy in a Patient with No Evidence of Sarcoid in Other Organs. Biopsy Consistent with Sarcoid 30% of Cases. Treat with Steroids Cardiac Amyloidosis Causes Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Myocyte Destruction and Replacement with Amyloid Fibrils (Beta Pleated Sheets) Leading to Progressive Thickening of the Ventricular Walls. More Common in Primary (AL) Amyloidosis, a Plasma Cell Dyscrasia Where Immunoglobulins Form Amyloid Protein Cardiac Amyloidosis EKG: Often Have Bundle Branch Block, Low Voltage Despite Thick Ventricles, or A-Fib Most Patients with Amyloidosis, Even Those with no Cardiac Symptoms, Have Abnormal Echocardiograms with: Ventricular Wall Thickening (70%), Isolated Septal Wall Thickening (30%), Diastolic Dysfunction (57%), Systolic Dysfunction (27%), Pericardial Effusion (40%), Myocardial Sparkling Pattern in 2D (27%) Cardiac Amyloidosis Diagnosis with Tissue Biopsy Revealing Amyloidosis, Often Abdominal Fat Pad Prognosis Less Than 1 Year, Survival at 5 Years <5% Treatment: Primary Amyliodosis Limited Benefit of Alkylating Agents Secondary Amyloidosis: Treat Underlying Disease Giant Cell Myocarditis Causes Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy Unknown Etiology Causes Progressive Left Ventricular Failure and Arrhythmias, Over Weeks to Months Rare, 80 Cases Reported by 1997 Average Age 43 (Infants to Elderly) Usually Affects Otherwise Healthy Patients Equal Predominance of Men and Women 90% Are Caucasian Giant Cell Myocarditis Diagnosed by Endomyocardial Biopsy Demonstrating: Diffuse Myocardial Necrosis with Multinucleated Giant Cells in the Absence of Sarcoid Like Granuloma. Inflammatory Infiltrate in Close Apposition to Myocyte Necrosis. Negative Culture and Stains for Infection, No Viral Particles on Electron Microscopy. Giant Cell Myocarditis 75% Present with CHF, 25% with Ventricular Arrhythmias, Sudden Cardiac Death (50%), Heart Block, Diffuse ST-T Abnormalities on EKG. May be Localized Rather Than Diffuse in Earlier Stages. There Are Case Reports of Giant Cell Myocarditis Affecting Only the Atria. 20% Have Other Autoimmune Disease: Hashimoto Thyroiditis, RA, MG, Takayasu Arteritis, Alopecia, Vitiligo, Pernicious Anemia, Crohn’s Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, ITP, Celiac Disease Giant Cell Myocarditis Survival 5.5 Months After Onset of Symptoms, Normally Succumb to CHF or Arrhythmia Immunosuppresive Therapy with Corticosteroids, Cyclosporin, Azathioprine Increases Survival to 12 Months, Case Reports of Dramatic Improvement with Immunotherapy Cardiac Transplantation (with 25% recurrence), 71% Survival at 5 Years The Giant Cell Myocarditis Treatment Trial and Registry, Randomized Controlled Trial of T-Cell Targeted Treatment with Muromonab-CD3 and Cyclosporine Possible Etiologies for This Case Tuberculous Pericarditis No Fever, No Exposure, Not Immunocompromized, Would Not Explain Abnormal Atrium Cardiac Sarcoidosis No Evidence of Systemic Sarcoid, Normal Left Ventricular Walls Cardiac Amyloidosis No Low Voltage EKG, No Ventricular Wall Thickening Giant Cell Myocarditis Time Course Is Consistant with Our Patient, Could Account for Symptoms of CHF, Effusions, and Abnormal Left Atrium Diagnosis Giant Cell Myocarditis Diagnostic Test of Choice: Endomyocardial Biopsy References Spodick DH. The Pericardium. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997 Braunwald E, Fauci AS. Harrison’s Textbook of Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill; 2001 Up To Date, 2007 Garay S, Rom WN. Tuberculosis. Boston: Libble, Brown & CO; 1996 Hall HD, Hammar SP. Pulmonary Pathology. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1994 Roth JA, Ruckdeschel JC. Weisenburger, T. H. Thoracic Oncology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1995 Murphy JG, Lloyd MA. Mayo Clinic Cardiology. Rochester: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press; 2007 Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Braunwald E. Braunwald’s Heart Disease. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005 Silver MD, Gotlieb AI, Schoen FJ. Cardiovascular Pathology. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2001 Cooper LT, Berry GJ, et al: Idiopathic Giant-Cell Myocarditis. NE J Medicine, June, 1997 Frustaci A, Chimenti C, et al: Giant Cell Myocarditis, Responding to Immunosuppressive Therapy. Chest, March, 2000 Cooper LT: Giant Cell Myocarditis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Herz, May, 2000 Rosenstein ED, Zucker MJ, et al: Giant Cell Myocarditis: Most Fatal of Autoimmune Diseases. Seminars in Arthrithritis and Rheumatism, August, 2000 Special Thanks To: Dr. Erwin Dr. Starr Dr. Hurley