The muscular system is the anatomical system of a species that

advertisement

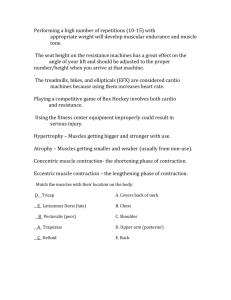

Muscular System Mohammed Jasim Uddin. Various muscles and it’s figures with details. Also discussed about the different activities of the muscles . Southern University Bangladesh. Jasimuddin_zia@ymail.co m +8801818183691 +0325-85451651 2/23/2011 Muscular system Muscular system Muscles anterior labeled Muscle posterior labeled Systema muscular The muscular system is the anatomical system of a species that allows it to move. The muscular system in vertebrates is controlled through the nervous system, although some muscles (such as the cardiac muscle) can be completely autonomous. Muscle A top-down view of skeletal muscle Muscle (from Latin musculus, diminutive of mus "mouse"[1]) is the contractile tissue of animals and is derived from the mesodermal layer of embryonic germ cells. Muscle cells contain contractile filaments that move past each other and change the size of the cell. They are classified as skeletal, cardiac, or smooth muscles. Their function is to produce force and cause motion. Muscles can cause either locomotion of the organism itself or movement of internal organs. Cardiac and smooth muscle contraction occurs without conscious thought and is necessary for survival. Examples are the contraction of the heart and peristalsis which pushes food through the digestive system. Voluntary contraction of the skeletal muscles is used to move the body and can be finely controlled. Examples are movements of the eye, or gross movements like the quadriceps muscle of the thigh. There are two broad types of voluntary muscle fibers: slow twitch and fast twitch. Slow twitch fibers contract for long periods of time but with little force while fast twitch fibers contract quickly and powerfully but fatigue very rapidly. Muscles are predominately powered by the oxidation of fats and carbohydrates, but anaerobic chemical reactions are also used, particularly by fast twitch fibers. These chemical reactions produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules which are used to power the movement of the myosin heads. Embryology All muscles derive from paraxial mesoderm.[2] The paraxial mesoderm is divided along the embryo's length into somites, corresponding to the segmentation of the body (most obviously seen in the vertebral column.[2] Each somite has 3 divisions, sclerotome (which forms vertebrae), dermatome (which forms skin), and myotome (which forms muscle).[2] The myotome is divided into two sections, the epimere and hypomere, which form epaxial and hypaxial muscles, respectively.Epaxial muscles in humans are only the erector spinae and small intervertebral muscles, and are innervated by the dorsal rami of the spinal nerves. All other muscles, including limb muscles, are hypaxial muscles, formed from the hypomere, and inervated by the ventral rami of the spinal nerves. During development, myoblasts (muscle progenitor cells) either remain in the somite to form muscles associated with the vertebral column or migrate out into the body to form all other muscles. Myoblast migration is preceded by the formation of connective tissue frameworks, usually formed from the somatic lateral plate mesoderm.[2]Myoblasts follow chemical signals to the appropriate locations, where they fuse into elongate skeletal muscle cells.[2] Types Types of muscle (shown at different magnifications) There are three types of muscle: Skeletal muscle or "voluntary muscle" is anchored by tendons (or by aponeuroses at a few places) to bone and is used to effect skeletal movement such as locomotion and in maintaining posture. Though this postural control is generally maintained as a subconscious reflex, the muscles responsible react to conscious control like non-postural muscles. An average adult male is made up of 42% of skeletal muscle and an average adult female is made up of 36% (as a percentage of body mass).[3] Smooth muscle or "involuntary muscle" is found within the walls of organs and structures such as the esophagus, stomach, intestines, bronchi, uterus, urethra, bladder, blood vessels, and the arrector pili in the skin (in which it controls erection of body hair). Unlike skeletal muscle, smooth muscle is not under conscious control. Cardiac muscle is also an "involuntary muscle" but is more akin in structure to skeletal muscle, and is found only in the heart. Cardiac and skeletal muscles are "striated" in that they contain sarcomeres and are packed into highly regular arrangements of bundles; smooth muscle has neither. While skeletal muscles are arranged in regular, parallel bundles, cardiac muscle connects at branching, irregular angles (called intercalated discs). Striated muscle contracts and relaxes in short, intense bursts, whereas smooth muscle sustains longer or even near-permanent contractions. Skeletal muscle is further divided into several subtypes: Type I, slow oxidative, slow twitch, or "red" muscle is dense with capillaries and is rich in mitochondria and myoglobin, giving the muscle tissue its characteristic red color. It can carry more oxygen and sustain aerobic activity. Type II, fast twitch muscle, has three major kinds that are, in order of increasing contractile speed:[4] o Type IIa, which, like slow muscle, is aerobic, rich in mitochondria and capillaries and appears red. o Type IIx (also known as type IId), which is less dense in mitochondria and myoglobin. This is the fastest muscle type in humans. It can contract more quickly and with a greater amount of force than oxidative muscle, but can sustain only short, anaerobic bursts of activity before muscle contraction becomes painful (often incorrectly attributed to a build-up of lactic acid). N.B. in some books and articles this muscle in humans was, confusingly, called type IIB.[5] o Type IIb, which is anaerobic, glycolytic, "white" muscle that is even less dense in mitochondria and myoglobin. In small animals like rodents this is the major fast muscle type, explaining the pale color of their flesh. Anatomy: Muscles, anterior view (See Gray's muscle Muscles, posterior view (See Gray's muscle pictures for detailed pictures) pictures for detailed pictures) The anatomy of muscles includes both gross anatomy, comprising all the muscles of an organism, and, on the other hand, microanatomy, which comprises the structures of a single muscle. Smooth muscle Smooth muscle Layers of Esophageal Wall: 1. Mucosa 2. Submucosa 3. Muscularis 4. Adventitia 5. Striated muscle 6. Striated and smooth 7. Smooth muscle 8. Lamina muscularis mucosae 9. Esophageal glands Smooth muscle is an involuntary non-striated muscle. It is divided into two sub-groups; the single-unit (unitary) and multiunit smooth muscle. Within single-unit smooth muscle tissues, the autonomic nervous system innervates a single cell within a sheet or bundle and the action potential is propagated by gap junctions to neighboring cells such that the whole bundle or sheet contracts as a syncytium (i.e., a multinucleate mass of cytoplasm that is not separated into cells). Multiunit smooth muscle tissues innervate individual cells; as such, they allow for fine control and gradual responses, much like motor unit recruitment in skeletal muscle. Smooth muscle is found within the walls of blood vessels (such smooth muscle specifically being termed vascular smooth muscle) such as in the tunica media layer of large (aorta) and small arteries, arterioles and veins. Smooth muscle is also found in lymphatic vessels, the urinary bladder, uterus (termed uterine smooth muscle), male and female reproductive tracts, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, arrector pili of skin, the ciliary muscle, and iris of the eye. The structure and function is basically the same in smooth muscle cells in different organs, but the inducing stimuli differ substantially, in order to perform individual effects in the body at individual times. In addition, the glomeruli of the kidneys contain a smooth muscle-like cells called mesangial cells. Structure Most smooth muscle is of the single-unit variety, that is, either the whole muscle contracts or the whole muscle relaxes, but there is multiunit smooth muscle in the trachea, the large elastic arteries, and the iris of the eye. Single unit smooth muscle, however, is most common and lines blood vessels (except large elastic arteries), the urinary tract, and the digestive tract. Smooth muscle is fundamentally different from skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle in terms of structure, function, regulation of contraction, and excitation-contraction coupling. Smooth muscle fibers have a fusiform shape and, like striated muscle, can tense and relax. However, smooth muscle containing tissue tend to demonstrate greater elasticity and function within a larger length-tension curve than striated muscle. This ability to stretch and still maintain contractility is important in organs like the intestines and urinary bladder. In the relaxed state, each cell is spindle-shaped, 20-500 micrometers in length. Molecular structure A substantial portion of the volume of the cytoplasm of smooth muscle cells are taken up by the molecules myosin and actin,[1] which together have the capability to contract, and, through a chain of tensile structures, make the entire smooth muscle tissue contract with them. Myosin Myosin is primarily of class II in smooth muscle.[2] Myosin II contains two heavy chains which constitute the head and tail domains. Each of these heavy chains contains the N-terminal head domain, while the C-terminal tails take on a coiled-coil morphology, holding the two heavy chains together (imagine two snakes wrapped around each other, such as in a caduceus). Thus, myosin II has two heads. In smooth muscle, there is a single gene (MYH11[3]) that codes for the heavy chains myosin II, but there are splice variants of this gene that result in four distinct isoforms.[2] Also, smooth muscle may contain MHC that is not involved in contraction, and that can arise from multiple genes.[2] Myosin II also contains 4 light chains, resulting in 2 per head, weighing 20 (MLC20) and 17 (MLC17) kDa.[2] These bind the heavy chains in the "neck" region between the head and tail. o The MLC20 is also known as the regulatory light chain and actively participates in muscle contraction.[2] Two MLC20 isoforms are found in smooth muscle, and they are encoded by different genes, but only one isoform participates in contractility.[2] o The MLC17 is also known as the essential light chain.[2] Its exact function is unclear, but it's believed that it contributes to the structural stability of the myosin head along with MLC20.[2] Two variants of MLC17 (MLC17a/b) exist as a result of alternate splicing at the MLC17 gene.[2] Different combinations of heavy and light chains allow for up to hundreds of different types of myosin structures, but it is unlikely that more than a few such combinations are actually used or permitted within a specific smooth muscle bed.[2] In the uterus, a shift in myosin expression has been hypothesized to avail for changes in the directions of uterine contractions that are seen during the menstrual cycle.[2] Actin The thin filaments that form part of the contractile machinery are predominantly composed of αand γ-actin.[2] Smooth muscle α-actin (alpha actin) is the predominate isoform within smooth muscle. There are also lots of actin (mainly β-actin) that does not take part in contraction, but that polymerizes just below the plasma membrane in the presence of a contractile stimulant and, and may thereby assist in mechanical tension.[2] The ratio of actin to myosin is between 2:1[2] and 10:1[2] in smooth muscle, compared to ~6:1 in skeletal muscle and 4:1 in cardiac muscle. Smooth muscle does not contain the protein troponin; instead calmodulin (which takes on the regulatory role in smooth muscle), caldesmon and calponin are significant proteins expressed within smooth muscle. Tropomyosin is present in smooth but doesn't serve the same regulatory function as in striated muscle. Other tensile structures The myosin and actin form the contractile parts of continuous chains of tensile structures that stretch both across and between smooth muscle cells. The actin filaments of contractile units are attached to dense bodies. Dense bodies are rich in αactinin,[2] and also attach intermediate filaments (consisting largely of vimentin and desmin), and thereby appear to serve as anchors from which the thin filaments can exert force.[2] Dense bodies also are associated with β-actin, which is the type found in the cytoskeleton, suggesting that dense bodies may coordinate tensions from both the contractile machinery and the cytoskeleton.[2] The intermediate filaments are connected to other intermediate filaments via dense bodies, which eventually are attached to adherens junctions (also called focal adhesions) in the cell membrane of the smooth muscle cell, called the sarcolemma. The adherens junctions consist of large number of proteins including α-actinin, vinculin and cytoskeletal actin.[2] The adherens junctions are scattered around dense bands that are circumfering the smooth muscle cell in a rib-like pattern.[1] The dense band (or dense plaques)areas alternate with regions of membrane containing numerous caveolae. When actin and myosin interact, force is transduced to the sarcolemma. Smooth muscle cells have been observed contracting in a spiral corkscrew fashion, and contractile proteins have been observed organizing into zones of actin and myosin along the axis of the cell. The number of myosin filaments is dynamic between the relaxed and contracted state in some tissues as the ratio of actin to myosin changes, and the length and number of myosin filaments change. Smooth muscle-containing tissue often must be stretched, so elasticity is an important attribute of smooth muscle. Smooth muscle cells may secrete a complex extracellular matrix containing collagen (predominantly types I and III), elastin, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans. These fibers with their extracellular matrices contribute to the viscoelasticity of these tissues. The great arteries are viscolelastic vessels that act like a Windkessel propagating ventricular contraction and smoothing out the pulsatile flow. Smooth muscle also has specific elastin and collagen receptors to interact with these proteins. Caveolae The sarcolemma also contains caveolae, which are microdomains of lipid rafts specialized to cell-signaling events and ion channels. These invaginations in the sarcoplasma contain a host of receptors (prostacyclin, endothelin, serotonin, muscarinic receptors, adrenergic receptors), second messenger generators (adenylate cyclase, Phospholipase C), G proteins (RhoA, G alpha), kinases (rho kinase-ROCK, Protein kinase C, Protein Kinase A), ion channels (L type Calcium channels, ATP sensitive Potassium channels, Calcium sensitive Potassium channels) in close proximity. The caveolae are often close to sarcoplasmic reticulum or mitochondria, and have been proposed to organize signaling molecules in the membrane. Excitation-contraction coupling A smooth muscle is excited by external stimuli, which causes contraction. Each step is further detailed below. Inducing stimuli and factors Smooth muscle may contract spontaneously (via ionic channel dynamics) or as in the gut special pacemakers cells interstitial cells of Cajal produce rhythmic contractions. Also, contraction, as well as relaxation, can be induced by a number of physiochemical agents (e.g., hormones, drugs, neurotransmitters - particularly from the autonomic nervous system. Smooth muscle in various regions of the vascular tree, the airway and lungs, kidneys and vagina is different in their expression of ionic channels, hormone receptors, cell-signaling pathways, and other proteins that determine function. External substances For instance, most blood vessels respond to norepinephrine and epinephrine (from sympathetic stimulation or the adrenal medulla)by producing vasoconstriction (this response is mediated through alpha 1-adrenergic receptors). Blood vessels in skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle respond to these catecholamines producing vasodilation because the smooth muscle possess beta-adrenergic receptors. Generally, arterial smooth muscle responds to carbon dioxide by producing vasodilation, and responds to oxygen by producing vasoconstriction. Plumonary blood vessels within the lung are unique as they vasodilate to high oxygen tension and vasoconstrict when it falls. Bronchiole smooth muscle that lines the airways of the lung respond to high carbon dioxide producing vasodilation and vasoconstrict when carbon dioxide is low. These responses to carbon dioxide and oxygen by pulmonary blood vessels and bronchiole airway smooth muscle aid in matching perfusion and ventilation within the lungs. Further different smooth muscle tissues display extremes of abundant to little sarcoplasmic reticulum so excitation-contraction coupling varies with its dependence on intracellular or extracellular calcium. Stretch Recent research indicates that sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) signaling is an important regulator of vascular smooth muscle contraction. When transmural pressure increases, sphingosine kinase 1 phosphorylates sphingosine to S1P, which binds to the S1P2 receptor in plasma membrane of cells. This leads to a transient increase in intracellular calcium, and activates Rac and Rhoa signaling pathways. Collectively, these serve to increase MLCK activity and decrease MLCP activity, promoting muscle contraction. This allows arterioles to increase resistance in response to increased blood pressure and thus maintain constant blood flow. The Rhoa and Rac portion of the signaling pathway provides a calcium-independent way to regulate resistance artery tone.[4] Spread of impulse To maintain organ dimensions against force, cells are fastened to one another by adherens junctions. As a consequence, cells are mechanically coupled to one another such that contraction of one cell invokes some degree of contraction in an adjoining cell. Gap junctions couple adjacent cells chemically and electrically, facilitating the spread of chemicals (e.g., calcium) or action potentials between smooth muscle cells. Single unit smooth muscle displays numerous gap junctions and these tissues often organize into sheets or bundles which contract in bulk. Contraction Smooth muscle contraction is caused by the sliding of myosin and actin filaments (a sliding filament mechanism) over each other. The energy for this to happen is provided by the hydrolysis of ATP. Myosin functions as an ATPase utilizing ATP to produce a molecular conformational change of part of the myosin and produces movement. Movement of the filaments over each other happens when the globular heads protruding from myosin filaments attach and interact with actin filaments to form crossbridges. The myosin heads tilt and drag along the actin filament a small distance (10-12 nm). The heads then release the actin filament and then changes angle to relocate to another site on the actin filament a further distance (1012 nm) away. They can then re-bind to the actin molecule and drag it along further. This process is called crossbridge cycling and is the same for all muscles (see muscle contraction). Unlike cardiac and skeletal muscle, smooth muscle does not contain the calcium-binding protein troponin. Contraction is initiated by a calcium-regulated phosphorylation of myosin, rather than a calcium-activated troponin system. Crossbridge cycling causes contraction of myosin and actin complexes, in turn causing increased tension along the entire chains of tensile structures, ultimately resulting in contraction of entire smooth muscles. Phasic or tonic Smooth muscle may contract phasically with rapid contraction and relaxation, or tonically with slow and sustained contraction. The reproductive, digestive, respiratory, and urinary tracts, skin, eye, and vasculature all contain this tonic muscle type. This type of smooth muscle can maintain force for prolonged time with only little energy utilization. There are differences in the myosin heavy and light chains that also correlate with these differences in contractile patterns and kinetics of contraction between tonic and phasic smooth muscle. Activation of myosin heads Crossbridge cycling cannot occur until the myosin heads have been activated to allow crossbridges to form. When the light chains are phosphorylated, they become active and will allow contraction to occur. The enzyme that phosphorylates the light chains is called myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK), also called MLC20 kinase.[2] In order to control contraction, MLCK will work only when the muscle is stimulated to contract. Stimulation will increase the intracellular concentration of calcium ions. These bind to a molecule called calmodulin, and form a calcium-calmodulin complex. It is this complex that will bind to MLCK to activate it, allowing the chain of reactions for contraction to occur. Activation consists of phosphorylation of a serine on position 19 (Ser19) on the MLC20 light chain, which causes a conformational change that increases the angle in the neck domain of the myosin heavy chain,[2] which corresponds to the part of the cross-bridge cycle where the myosin head is unattached to the actin filament and relocates to another site on it. After attachment of the mysin head to the actin filament, this serine phosphorylation also activates the ATPase activity of the myosin head region to provide the energy to fuel the subsequent contraction.[2] Phosphorylation of a threonine on position 18 (Thr18) on MLC20 is also possible and may further increase the ATPase activity of the myosin complex.[2] Sustained maintenance Phosphorylation of the MLC20 myosin light chains correlates well with the shortening velocity of smooth muscle. During this period there is a rapid burst of energy utilization as measured by oxygen consumption. Within a few minutes of initiation the calcium level markedly decrease, MLC20 myosin light chains phosphorylation decreases, and energy utilization decreases and the muscle can relax. Still, smooth muscle has the ability of sustained maintenance of force in this situation as well. This sustained phase has been attributed to certain myosin crossbridges, termed latch-bridges, that are cycling very slowly, notably at the cycle stage where dephosphorylated myosin complexes detach from the actin, thereby maintaining the force at low energy costs.[2] This phenomenon is of great value especially for tonically active smooth muscle.[2] Isolated preparations of vascular and visceral smooth muscle contract with depolarizing high potassium balanced saline generating a certain amount of contractile force. The same preparation stimulated in normal balanced saline with an agonist such as endothelin or serotonin will generate more contractile force. This increase in force is termed calcium sensitization. The myosin light chain phosphatase is inhibited to increase the gain or sensitivity of myosin light chain kinase to calcium. There are number of cell signalling pathways believed to regulate this decrease in myosin light chain phosphatase: a RhoA-Rock kinase pathway, a Protein kinase CProtein kinase C potentiation inhibitor protein 17 (CPI-17) pathway, telokin, and a Zip kinase pathway. Further Rock kinase and Zip kinase have been implicated to directly phosphorylate the 20kd myosin light chains. Other contractile mechanisms Other cell signaling pathways and protein kinases (Protein kinase C, Rho kinase, Zip kinase, Focal adhesion kinases) have been implicated as well and actin polymerization dynamics plays a role in force maintenance. While myosin light chain phosphorylation correlates well with shortening velocity, other cell signaling pathways have been implicated in the development of force and maintenance of force. Notably the phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues on the focal adhesion adapter protein-paxillin by specific tyrosine kinases has been demonstrated to be essential to force development and maintenance. Cyclic nucleotides can relax arterial smooth muscle without reductions in crossbridge phosphorylation, a process termed force suppression. This process is mediated by the phosphorylation of the small heat shock protein, hsp20, and may prevent phosphorylated myosin heads from interacting with actin. Relaxation The phosphorylation of the light chains by MLCK is countered by a myosin light-chain phosphatase, which dephosphorylates the MLC20 myosin light chains and thereby inhibits contraction.[2] Other signaling pathways have also been implicated in the regulation actin and myosin dynamics. In general, the relaxation of smooth muscle is by cell-signaling pathways that increase the myosin phosphatase activity, decrease the intracellular calcium levels, hyperpolarize the smooth muscle, and/or regulate actin and myosin dynamics. Relaxation-inducing factors The relaxation of smooth muscle can be mediated by the endothelium-derived relaxing factornitric oxide, endothelial derived hyperpolarizing factor (either an endogenous cannabinoid, cytochrome P450 metabolite, or hydrogen peroxide), or prostacyclin (PGI2). Nitric oxide and PGI2 stimulate soluble guanylate cyclase and membrane bound adenylate cyclase, respectively. The cyclic nucleotides (cGMP and cAMP) produced by these cyclases activate Protein Kinase G and Proten Kinase A and phosphorylate a number of proteins. The phosphorylation events lead to a decrease in intracelluar calcium (inhibit L type Calcium channels, inhibits IP3 receptor channels, stimulates sarcoplasmic reticulum Calcium pump ATPase), a decrease in the 20kd myosin light chain phosphorylation by altering calcium sensitization and increasing myosin light chain phosphatase activity, a stimulation of calcium sensitive potassium channels which hyperpolarize the cell, and the phosphorylation of amino acid residue serine 16 on the small heat shock protein (hsp20)by Protein Kinases A and G. The phosphorylation of hsp20 appears to alter actin and focal adhesion dynamics and actin-myosin interaction, and recent evidence indicates that hsp20 binding to 14-3-3 protein is involved in this process. An alternative hypothesis is that phosphorylated Hsp20 may also alter the affinity of phosphorylated myosin with actin and inhibit contractility by interfering with crossbridge formation. The endothelium derived hyperpolarizing factor stimulates calcium sensitive potassium channels and/or ATP sensitive potassium channels and stimulate potassium efflux which hyperpolarizes the cell and produces relaxation. Invertebrate smooth muscle In invertebrate smooth muscle, contraction is initiated with the binding of calcium directly to myosin and then rapidly cycling cross-bridges, generating force. Similar to the mechanism of vertebrate smooth muscle, there is a low calcium and low energy utilization catch phase. This sustained phase or catch phase has been attributed to a catch protein that has similarities to myosin light-chain kinase and the elastic protein-titin called twitchin. Clams and other bivalve mollusks use this catch phase of smooth muscle to keep their shell closed for prolonged periods with little energy usage. Specific effects Although the structure and function is basically the same in smooth muscle cells in different organs, their specific effects or end-functions differ. Smooth muscle forms precapillary sphincters in blood vessels in metarterioles which regulates the blood flow in capillary beds of various organs and tissues. The contractile function of vascular smooth muscle also regulates the lumenal diameter of the small arteries-arterioles called resistance vessels, thereby contributing significantly to setting the level of blood pressure. Smooth muscle contracts slowly and may maintain the contraction (tonically) for prolonged periods in blood vessels, bronchioles, and some sphincters. Activating arteriole smooth muscle can decrease the lumenal diameter 1/3 of resting so it drastically alters blood flow and resistance. Activation of aortic smooth muscle doesn't significantly alter the lumenal diameter but serves to increase the viscoelasticity of the vascular wall. In the digestive tract, smooth muscle contracts in a rhythmic peristaltic fashion, rhythmically forcing foodstuffs through the digestive tract as the result of phasic contraction. A non-contractile function is seen in specialized smooth muscle within the afferent arteriole of the juxtaglomerular apparatus, which secretes renin in response to osmotic and pressure changes, and also it is believed to secrete ATP in tubuloglomerular regulation of glomerular filtration rate. Renin in turn activates the renin-angiotensin system to regulate blood pressure. Growth and rearrangement The mechanism in which external factors stimulate growth and rearrangement is not yet fully understood. A number of growth factors and neurohumoral agents influence smooth muscle growth and differentiation. The Notch receptor and cell-signaling pathway have been demonstrated to be essential to vasculogenesis and the formation of arteries and veins. The embryological origin of smooth muscle is usually of mesodermal origin. However, the smooth muscle within the Aorta and Pulmonary arteries (the Great Arteries of the heart) is derived from ectomesenchyme of neural crest origin, although coronary artery smooth muscle is of mesodermal origin. Cardiac muscle (Redirected from Heart muscle) cardiac muscle Cardiac muscle is a type of involuntary striated muscle found in the walls and histologic foundation of the heart, specifically the myocardium. Cardiac muscle is one of three major types of muscle, the others being skeletal and smooth muscle. The cells that comprise cardiac muscle, called myocardiocyteal muscle cells, are mononuclear, like smooth muscle cells.[1] Coordinated contractions of cardiac muscle cells in the heart propel blood out of the atria and ventricles to the blood vessels of the left/body/systemic and right/lungs/pulmonary circulatory systems. This complex of actions makes up the systole of the heart. Cardiac muscle cells, like all tissues in the body, rely on an ample blood supply to deliver oxygen and nutrients and to remove waste products such as carbon dioxide. The coronary arteries fulfill this function. Dog Cardiac Muscle 400X Metabolism Cardiac muscle is adapted to be highly resistant to fatigue: it has a large number of mitochondria, enabling continuous aerobic respiration via oxidative phosphorylation, numerous myoglobins (oxygen-storing pigment) and a good blood supply, which provides nutrients and oxygen. The heart is so tuned to aerobic metabolism that it is unable to pump sufficiently in ischaemic conditions. At basal metabolic rates, about 1% of energy is derived from anaerobic metabolism. This can increase to 10% under moderately hypoxic conditions, but, under more severe hypoxic conditions, not enough energy can be liberated by lactate production to sustain ventricular contractions.[2] Under basal aerobic conditions, 60% of energy comes from fat (free fatty acids and triglycerides), 35% from carbohydrates, and 5% from amino acids and ketone bodies. However, these proportions vary widely according to nutritional state. For example, during starvation, lactate can be recycled by the heart. This is very energy efficient, because one NAD+ is reduced to NADH and H+ (equal to 2.5 or 3 ATP) when lactate is oxidized to pyruvate, which can then be burned aerobically in the TCA cycle, liberating much more energy (ca 14 ATP per cycle). In the condition of diabetes, more fat and less carbohydrate is used due to the reduced induction of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell surfaces. However, contraction itself plays a part in bringing GLUT4 transporters to the surface.[3] This is true of skeletal muscle as well, but relevant in particular to cardiac muscle due to its continuous contractions. Appearance Striation Cardiac muscle exhibits cross striations formed by alternating segments of thick and thin protein filaments. Like skeletal muscle, the primary structural proteins of cardiac muscle are actin and myosin. The actin filaments are thin causing the lighter appearance of the I bands in striated muscle, while the myosin filament is thicker lending a darker appearance to the alternating A bands as observed with electron microscopy. However, in contrast to skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle cells may be branched instead of linear and longitudinal. T-Tubules Another histological difference between cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle is that the T-tubules in the cardiac muscle are larger, broader and run along the Z-Discs. There are fewer T-tubules in comparison with skeletal muscle. Additionally, cardiac muscle forms diads instead of the triads formed between the T-tubules and the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle. T-tubules play critical role in excitation-contraction coupling (ECC). Recently, the action potentials of Ttubules were recorded optically by Guixue Bu et al.[4] Intercalated discs Intercalated discs (IDs) are complex adhering structures which connect single cardiac myocytes to an electrochemical syncytium (in contrast to the skeletal muscle, which becomes a multicellular syncytium during mammalian embryonic development) and are mainly responsible for force transmission during muscle contraction. Intercalated discs also support the rapid spread of action potentials and the synchronized contraction of the myocardium. IDs are described to consist of three different types of cell-cell junctions: the actin filament anchoring adherens junctions (fascia adherens), the intermediate filament anchoring desmosomes (macula adherens) and gap junctions. Gap junctions are responsible for electrochemical and metabolic coupling. They allow action potentials to spread between cardiac cells by permitting the passage of ions between cells, producing depolarization of the heart muscle. However, novel molecular biological and comprehensive studies unequivocally showed that IDs consist for the most part of mixed type adhering junctions named area composita (pl. areae compositae) representing an amalgamation of typical desmosomal and fascia adhaerens proteins (in contrast to various epithelia)[citation needed]. The authors discuss the high importance of these findings for the understanding of inherited cardiomyopathies (such as Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy, ARVC). Under light microscopy, intercalated discs appear as thin, typically dark-staining lines dividing adjacent cardiac muscle cells. The intercalated discs run perpendicular to the direction of muscle fibers. Under electron microscopy, an intercalated disc's path appears more complex. At low magnification, this may appear as a convoluted electron dense structure overlying the location of the obscured Z-line. At high magnification, the intercalated disc's path appears even more convoluted, with both longitudinal and transverse areas appearing in longitudinal section.[5] Role of calcium in contraction In contrast to skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle requires extracellular calcium ions for contraction to occur. Like skeletal muscle,the initiation and upshoot of the action potential in ventricular muscle cells is derived from the entry of sodium ions across the sarcolemma in a regenerative process. However, an inward flux of extracellular calcium ions through L-type calcium channels sustains the depolarization of cardiac muscle cells for a longer duration. The reason for the calcium dependence is due to the mechanism of calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) from the sarcoplasmic reticulum that must occur under normal excitation-contraction (EC) coupling to cause contraction. Once the intracellular concentration of calcium increases, calcium ions bind to the protein troponin, which initiates contraction by allowing the contractile proteins, myosin and actin to associate through cross-bridge formation. Cardiac muscle is intermediate between smooth muscle, which has an unorganized sarcoplasmic reticulum and derives its calcium from both the extracellular fluid and intracellular stores, and skeletal muscle, which is only activated by calcium stored in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Regeneration of heart muscle cells Until recently, it was commonly believed that cardiac muscle cells could not be regenerated. However, a study reported in the April 3, 2009 issue of Science contradicts that belief.[6] Olaf Bergmann and his colleagues at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm tested samples of heart muscle from people born before 1955 when nuclear bomb testing caused elevated levels of radioactive carbon 14 in the Earth's atmosphere. They found that samples from people born before 1955 did have elevated carbon 14 in their heart muscle cell DNA, indicating that the cells had divided after the person's birth. By using DNA samples from many hearts, the researchers estimated that a 20-year-old renews about 1% of heart muscle cells per year and about 45 percent of the heart muscle cells of a 50-year-old were generated after he or she was born. Gross anatomy The gross anatomy of a muscle is the most important indicator of its role in the body. The action a muscle generates is determined by the origin and insertion locations. The cross-sectional area of a muscle (rather than volume or length) determines the amount of force it can generate by defining the number of sarcomeres which can operate in parallel. The amount of force applied to the external environment is determined by lever mechanics, specifically the ratio of in-lever to out-lever. For example, moving the insertion point of the biceps more distally on the radius (farther from the joint of rotation) would increase the force generated during flexion (and, as a result, the maximum weight lifted in this movement), but decrease the maximum speed of flexion. Moving the insertion point proximally (closer to the joint of rotation) would result in decreased force but increased velocity. This can be most easily seen by comparing the limb of a mole to a horse - in the former, the insertion point is positioned to maximize force (for digging), while in the latter, the insertion point is positioned to maximize speed (for running). One particularly important aspect of gross anatomy of muscles is pennation or lack thereof. In most muscles, all the fibers are oriented in the same direction, running in a line from the origin to the insertion. In pennate muscles, the individual fibers are oriented at an angle relative to the line of action, attaching to the origin and insertion tendons at each end. Because the contracting fibers are pulling at an angle to the overall action of the muscle, the change in length is smaller, but this same orientation allows for more fibers (thus more force) in a muscle of a given size. Pennate muscles are usually found where their length change is less important than maximum force, such as the rectus femoris. There are approximately 639 skeletal muscles in the human body. However, the exact number is difficult to define because different sources group muscles differently and some muscles, such as palmaris longus, are variably present in humans. Microanatomy Muscle is mainly composed of muscle cells. Within the cells are myofibrils; myofibrils contain sarcomeres, which are composed of actin and myosin. Individual muscle fibres are surrounded by endomysium. Muscle fibers are bound together by perimysium into bundles called fascicles; the bundles are then grouped together to form muscle, which is enclosed in a sheath of epimysium. Muscle spindles are distributed throughout the muscles and provide sensory feedback information to the central nervous system. Skeletal muscle is arranged in discrete muscles, an example of which is the biceps brachii. It is connected by tendons to processes of the skeleton. Cardiac muscle is similar to skeletal muscle in both composition and action, being made up of myofibrils of sarcomeres, but anatomically different in that the muscle fibers are typically branched like a tree and connect to other cardiac muscle fibers through intercalcated discs, and form the appearance of a syncytium. Physiology The three types of muscle (skeletal, cardiac and smooth) have significant differences. However, all three use the movement of actin against myosin to create contraction. In skeletal muscle, contraction is stimulated by electrical impulses transmitted by the nerves, the motor nerves and motoneurons in particular. Cardiac and smooth muscle contractions are stimulated by internal pacemaker cells which regularly contract, and propagate contractions to other muscle cells they are in contact with. All skeletal muscle and many smooth muscle contractions are facilitated by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Muscular activity accounts for much of the body's energy consumption. All muscle cells produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules which are used to power the movement of the myosin heads. Muscles conserve energy in the form of creatine phosphate which is generated from ATP and can regenerate ATP when needed with creatine kinase. Muscles also keep a storage form of glucose in the form of glycogen. Glycogen can be rapidly converted to glucose when energy is required for sustained, powerful contractions. Within the voluntary skeletal muscles, the glucose molecule can be metabolized anaerobically in a process called glycolysis which produces two ATP and two lactic acid molecules in the process (note that in aerobic conditions, lactate is not formed; instead pyruvate is formed and transmitted through the citric acid cycle). Muscle cells also contain globules of fat, which are used for energy during aerobic exercise. The aerobic energy systems take longer to produce the ATP and reach peak efficiency, and requires many more biochemical steps, but produces significantly more ATP than anaerobic glycolysis. Cardiac muscle on the other hand, can readily consume any of the three macronutrients (protein, glucose and fat) aerobically without a 'warm up' period and always extracts the maximum ATP yield from any molecule involved. The heart, liver and red blood cells will also consume lactic acid produced and excreted by skeletal muscles during exercise. Nervous control Efferent leg The efferent leg of the peripheral nervous system is responsible for conveying commands to the muscles and glands, and is ultimately responsible for voluntary movement. Nerves move muscles in response to voluntary and autonomic (involuntary) signals from the brain. Deep muscles, superficial muscles, muscles of the face and internal muscles all correspond with dedicated regions in the primary motor cortex of the brain, directly anterior to the central sulcus that divides the frontal and parietal lobes. In addition, muscles react to reflexive nerve stimuli that do not always send signals all the way to the brain. In this case, the signal from the afferent fiber does not reach the brain, but produces the reflexive movement by direct connections with the efferent nerves in the spine. However, the majority of muscle activity is volitional, and the result of complex interactions between various areas of the brain. Nerves that control skeletal muscles in mammals correspond with neuron groups along the primary motor cortex of the brain's cerebral cortex. Commands are routed though the basal ganglia and are modified by input from the cerebellum before being relayed through the pyramidal tract to the spinal cord and from there to the motor end plate at the muscles. Along the way, feedback, such as that of the extrapyramidal system contribute signals to influence muscle tone and response. Deeper muscles such as those involved in posture often are controlled from nuclei in the brain stem and basal ganglia. Afferent leg The afferent leg of the peripheral nervous system is responsible for conveying sensory information to the brain, primarily from the sense organs like the skin. In the muscles, the muscle spindles convey information about the degree of muscle length and stretch to the central nervous system to assist in maintaining posture and joint position. The sense of where our bodies are in space is called proprioception, the perception of body awareness. More easily demonstrated than explained, proprioception is the "unconscious" awareness of where the various regions of the body are located at any one time. This can be demonstrated by anyone closing their eyes and waving their hand around. Assuming proper proprioceptive function, at no time will the person lose awareness of where the hand actually is, even though it is not being detected by any of the other senses. Several areas in the brain coordinate movement and position with the feedback information gained from proprioception. The cerebellum and red nucleus in particular continuously sample position against movement and make minor corrections to assure smooth motion. Exercise Exercise is often recommended as a means of improving motor skills, fitness, muscle and bone strength, and joint function. Exercise has several effects upon muscles, connective tissue, bone, and the nerves that stimulate the muscles. One such effect is muscle hypertrophy, an increase in size. This is used in bodybuilding. Various exercises require a predominance of certain muscle fiber utilization over another. Aerobic exercise involves long, low levels of exertion in which the muscles are used at well below their maximal contraction strength for long periods of time (the most classic example being the marathon). Aerobic events, which rely primarily on the aerobic (with oxygen) system, use a higher percentage of Type I (or slow-twitch) muscle fibers, consume a mixture of fat, protein and carbohydrates for energy, consume large amounts of oxygen and produce little lactic acid. Anaerobic exercise involves short bursts of higher intensity contractions at a much greater percentage of their maximum contraction strength. Examples of anaerobic exercise include sprinting and weight lifting. The anaerobic energy delivery system uses predominantly Type II or fast-twitch muscle fibers, relies mainly on ATP or glucose for fuel, consumes relatively little oxygen, protein and fat, produces large amounts of lactic acid and can not be sustained for as long a period as aerobic exercise. The presence of lactic acid has an inhibitory effect on ATP generation within the muscle; though not producing fatigue, it can inhibit or even stop performance if the intracellular concentration becomes too high. However, long-term training causes neovascularization within the muscle, increasing the ability to move waste products out of the muscles and maintain contraction. Once moved out of muscles with high concentrations within the sarcomere, lactic acid can be used by other muscles or body tissues as a source of energy, or transported to the liver where it is converted back to pyruvate. The ability of the body to export lactic acid and use it as a source of energy depends on training level.[citation needed] Humans are genetically predisposed with a larger percentage of one type of muscle group over another. An individual born with a greater percentage of Type I muscle fibers would theoretically be more suited to endurance events, such as triathlons, distance running, and long cycling events, whereas a human born with a greater percentage of Type II muscle fibers would be more likely to excel at anaerobic events such as a 200 meter dash, or weightlifting.[citation needed] Delayed onset muscle soreness is pain or discomfort that may be felt one to three days after exercising and subsides generally within two to three days later. Once thought to be caused by lactic acid buildup, a more recent theory is that it is caused by tiny tears in the muscle fibers caused by eccentric contraction, or unaccustomed training levels. Since lactic acid disperses fairly rapidly, it could not explain pain experienced days after exercise.[6] Muscular, spinal and neural factors all affect muscle building. Sometimes a person may notice an increase in strength in a given muscle even though only its opposite has been subject to exercise, such as when a bodybuilder finds her left biceps stronger after completing a regimen focusing only on the right biceps. This phenomenon is called cross education.[citation needed] Disease Symptoms of muscle diseases may include weakness, spasticity, myoclonus and myalgia. Diagnostic procedures that may reveal muscular disorders include testing creatine kinase levels in the blood and electromyography (measuring electrical activity in muscles). In some cases, muscle biopsy may be done to identify a myopathy, as well as genetic testing to identify DNA abnormalities associated with specific myopathies and dystrophies. Neuromuscular diseases are those that affect the muscles and/or their nervous control. In general, problems with nervous control can cause spasticity or paralysis, depending on the location and nature of the problem. A large proportion of neurological disorders leads to problems with movement, ranging from cerebrovascular accident (stroke) and Parkinson's disease to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. A non-invasive elastography technique that measures muscle noise is undergoing experimentation to provide a way of monitoring neuromuscular disease. The sound produced by a muscle comes from the shortening of actomyosin filaments along the axis of the muscle. During contraction, the muscle shortens along its longitudinal axis and expands across the transverse axis, producing vibrations at the surface.[7] Atrophy Main article: Muscle atrophy There are many diseases and conditions which cause a decrease in muscle mass, known as muscle atrophy. Examples include cancer and AIDS, which induce a body wasting syndrome called cachexia. Other syndromes or conditions which can induce skeletal muscle atrophy are congestive heart disease and some diseases of the liver. During aging, there is a gradual decrease in the ability to maintain skeletal muscle function and mass, known as sarcopenia. The exact cause of sarcopenia is unknown, but it may be due to a combination of the gradual failure in the "satellite cells" which help to regenerate skeletal muscle fibers, and a decrease in sensitivity to or the availability of critical secreted growth factors which are necessary to maintain muscle mass and satellite cell survival. Sarcopenia is a normal aspect of aging, and is not actually a disease state yet can be linked to many injuries in the elderly population as well as decreasing quality of life.[8] Atrophy is of particular interest to the manned spaceflight community, since the weightlessness experienced in spaceflight results is a loss of as much as 30% of mass in some muscles.[9][10] Physical inactivity and atrophy Inactivity and starvation in mammals lead to atrophy of skeletal muscle, accompanied by a smaller number and size of the muscle cells as well as lower protein content.[11] In humans, prolonged periods of immobilization, as in the cases of bed rest or astronauts flying in space, are known to result in muscle weakening and atrophy. Such consequences are also noted in small hibernating mammals like the golden-mantled ground squirrels and brown bats.[12] Bears are an exception to this rule; species in the family Ursidae are famous for their ability to survive unfavorable environmental conditions of low temperatures and limited nutrition availability during winter by means of hibernation. During that time, bears go through a series of physiological, morphological and behavioral changes.[13] Their ability to maintain skeletal muscle number and size at time of disuse is of a significant importance. During hibernation, bears spend four to seven months of inactivity and anorexia without undergoing muscle atrophy and protein loss.[12] There are a few known factors that contribute to the sustaining of muscle tissue. During the summer period, bears take advantage of the nutrition availability and accumulate muscle protein. The protein balance at time of dormancy is also maintained by lower levels of protein breakdown during the winter time.[12] At times of immobility, muscle wasting in bears is also suppressed by a proteolytic inhibitor that is released in circulation.[11] Another factor that contributes to the sustaining of muscle strength in hibernating bears is the occurrence of periodic voluntary contractions and involuntary contractions from shivering during torpor.[14] The three to four daily episodes of muscle activity are responsible for the maintenance of muscle strength and responsiveness in bears during hibernation.[14] Strength A display of "strength" (e.g. lifting a weight) is a result of three factors that overlap: physiological strength (muscle size, cross sectional area, available crossbridging, responses to training), neurological strength (how strong or weak is the signal that tells the muscle to contract), and mechanical strength (muscle's force angle on the lever, moment arm length, joint capabilities). Contrary to popular belief, the number of muscle fibres cannot be increased through exercise; instead the muscle cells simply get bigger. Muscle fibres have a limited capacity for growth through hypertrophy and some believe they split through hyperplasia if subject to increased demand.[citation needed] The "strongest" human muscle Since three factors affect muscular strength simultaneously and muscles never work individually, it is misleading to compare strength in individual muscles, and state that one is the "strongest". But below are several muscles whose strength is noteworthy for different reasons. In ordinary parlance, muscular "strength" usually refers to the ability to exert a force on an external object—for example, lifting a weight. By this definition, the masseter or jaw muscle is the strongest. The 1992 Guinness Book of Records records the achievement of a bite strength of 4,337 N (975 lbf) for 2 seconds. What distinguishes the masseter is not anything special about the muscle itself, but its advantage in working against a much shorter lever arm than other muscles. If "strength" refers to the force exerted by the muscle itself, e.g., on the place where it inserts into a bone, then the strongest muscles are those with the largest cross-sectional area. This is because the tension exerted by an individual skeletal muscle fiber does not vary much. Each fiber can exert a force on the order of 0.3 micronewton. By this definition, the strongest muscle of the body is usually said to be the quadriceps femoris or the gluteus maximus. A shorter muscle will be stronger "pound for pound" (i.e., by weight) than a longer muscle. The myometrial layer of the uterus may be the strongest muscle by weight in the human body. At the time when an infant is delivered, the entire human uterus weighs about 1.1 kg (40 oz). During childbirth, the uterus exerts 100 to 400 N (25 to 100 lbf) of downward force with each contraction. The external muscles of the eye are conspicuously large and strong in relation to the small size and weight of the eyeball. It is frequently said that they are "the strongest muscles for the job they have to do" and are sometimes claimed to be "100 times stronger than they need to be." However, eye movements (particularly saccades used on facial scanning and reading) do require high speed movements, and eye muscles are exercised nightly during rapid eye movement sleep. The statement that "the tongue is the strongest muscle in the body" appears frequently in lists of surprising facts, but it is difficult to find any definition of "strength" that would make this statement true. Note that the tongue consists of sixteen muscles, not one. The heart has a claim to being the muscle that performs the largest quantity of physical work in the course of a lifetime. Estimates of the power output of the human heart range from 1 to 5 watts. This is much less than the maximum power output of other muscles; for example, the quadriceps can produce over 100 watts, but only for a few minutes. The heart does its work continuously over an entire lifetime without pause, and thus does "outwork" other muscles. An output of one watt continuously for eighty years yields a total work output of two and a half gigajoules. Efficiency The efficiency of human muscle has been measured (in the context of rowing and cycling) at 18% to 26%. The efficiency is defined as the ratio of mechanical work output to the total metabolic cost, as can be calculated from oxygen consumption. This low efficiency is the result of about 40% effiency of generating ATP from food energy, losses in converting energy from ATP into mechanical work inside the muscle, and mechanical losses inside the body. The latter two losses are dependent on the type of exercise and the type of muscle fibers being used (fasttwitch or slow-twitch). For an overal efficiency of 20 percent, one watt of mechanical power is equivalent to 4.3 kcal per hour. For example, a manufacturer of rowing equipment shows burned calories as four times the actual mechanical work, plus 300 kcal per hour,[15] which amounts to about 20 percent efficiency at 250 watts of mechanical output. The mechanical energy output of a cyclic contraction can depend upon many factors, including activation timing, muscle strain trajectory, and rates of force rise & decay. These can be synthesized experimentally using work loop analysis. Density of muscle tissue compared to adipose tissue The density of mammalian skeletal muscle tissue is about 1.06 kg/liter.[16] This can be contrasted with the density of adipose tissue (fat), which is 0.9196 kg/liter.[17] This makes muscle tissue approximately 15% denser than fat tissue. Resting energy expenditure of muscle At rest, skeletal muscle consumes 54.4 kJ/kg (13.0 kcal/kg) per day. This is larger than adipose tissue (fat) at 18.8 kJ/kg (4.5 kcal/kg), and bone at 9.6 kJ/kg (2.3 kcal/kg).[18] Muscle evolution Evolutionarily, specialized forms of skeletal and cardiac muscles predated the divergence of the vertebrate/arthropod evolutionary line.[19] This indicates that these types of muscle developed in a common ancestor sometime before 700 million years ago (mya). Vertebrate smooth muscle was found to have evolved independently from the skeletal and cardiac muscles. There are three distinct types of muscles: skeletal muscles, cardiac or heart muscles, and smooth (non-striated) muscles. Muscles provide strength, balance, posture, movement and heat for the body to keep warm. Upon stimulation by an action potential, skeletal muscles perform a coordinated contraction by shortening each sarcomere. The best proposed model for understanding contraction is the sliding filament model of muscle contraction. Actin and myosin fibers overlap in a contractile motion towards each other. Myosin filaments have club-shaped heads that project toward the actin filaments. Larger structures along the myosin filament called myosin heads are used to provide attachment points on binding sites for the actin filaments. The myosin heads move in a coordinated style, they swivel toward the center of the sarcomere, detach and then reattach to the nearest active site of the actin filament. This is called a rachet type drive system. This process consumes large amounts of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Energy for this comes from ATP, the energy source of the cell. ATP binds to the cross bridges between myosin heads and actin filaments. The release of energy powers the swiveling of the myosin head. Muscles store little ATP and so must continuously recycle the discharged adenosine diphosphate molecule (ADP) into ATP rapidly. Muscle tissue also contains a stored supply of a fast acting recharge chemical, creatine phosphate which can assist initially producing the rapid regeneration of ADP into ATP. Calcium ions are required for each cycle of the sarcomere. Calcium is released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum into the sarcomere when a muscle is stimulated to contract. This calcium uncovers the actin binding sites. When the muscle no longer needs to contract, the calcium ions are pumped from the sarcomere and back into storage in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Anatomy There are approximately 639 skeletal muscles in the human body.The following are some major muscles[1] and their basic features: Aerobic and anaerobic muscle activity At rest, the body produces the majority of its ATP aerobically in the mitochondria[2] without producing lactic acid or other fatiguing byproducts.[3] During exercise, the method of ATP production varies depending on the fitness of the individual as well as the duration, and intensity of exercise. At lower activity levels, when exercise continues for a long duration (several minutes or longer), energy is produced aerobically by combining oxygen with carbohydrates and fats stored in the body. Activity that is higher in intensity, with possible duration decreasing as intensity increases, ATP production can switch to anaerobic pathways, such as the use of the creatine phosphate and the phosphagen system or anaerobic glycolysis. Aerobic ATP production is biochemically much slower and can only be used for long-duration, low intensity exercise, but produces no fatiguing waste products that can not be removed immediately from sarcomere and body and results in a much greater number of ATP molecules per fat or carbohydrate molecule. Aerobic training allows the oxygen delivery system to be more efficient, allowing aerobic metabolism to begin quicker.[3] Anaerobic ATP production produces ATP much faster and allows near-maximal intensity exercise, but also produces significant amounts of lactic acid which render high intensity exercise unsustainable for greater than several minutes.[3] The phosphagen system is also anaerobic, allows for the highest levels of exercise intensity, but intramuscular stores of phosphocreatine are very limited and can only provide energy for exercises lasting up to ten seconds. Recovery is very quick, with full creatine stores regenerated within five minutes.[3] Cardiac muscle Heart muscles are distinct from skeletal muscles because the muscle fibers are laterally connected to each other. Furthermore, just as with smooth muscles, they are not controlling themselves. Heart muscles are controlled by the sinus node influenced by the autonomic nervous system. Smooth muscle Smooth muscles are controlled directly by the autonomic nervous system and are involuntary, meaning that they are incapable of being moved by conscious thought. Functions such as heart beat and lungs (which are capable of being willingly controlled, be it to a limited extent) are involuntary muscles but are not smooth muscles. Control of muscle contraction Neuromuscular junctions are the focal point where a motor neuron attaches to a muscle. Acetylcholine, (a neurotransmitter used in skeletal muscle contraction) is released from the axon terminal of the nerve cell when an action potential reaches the microscopic junction, called a synapse. A group of chemical messengers cross the synapse and stimulate the formation of electrical changes, which are produced in the muscle cell when the acetylcholine binds to receptors on its surface. Calcium is released from its storage area in the cell's sarcoplasmic reticulum. An impulse from a nerve cell causes calcium release and brings about a single, short muscle contraction called a muscle twitch. If there is a problem at the neuromuscular junction, a very prolonged contraction may occur, tetanus. Also, a loss of function at the junction can produce paralysis. Skeletal muscles are organized into hundreds of motor units, each of which involves a motor neuron, attached by a series of thin finger-like structures called axon terminals. These attach to and control discrete bundles of muscle fibers. A coordinated and fine tuned response to a specific circumstance will involve controlling the precise number of motor units used. While individual muscle units contract as a unit, the entire muscle can contract on a predetermined basis due to the structure of the motor unit. Motor unit coordination, balance, and control frequently come under the direction of the cerebellum of the brain. This allows for complex muscular coordination with little conscious effort, such as when one drives a car without thinking about the process.