The review essay - Göteborgs universitet

advertisement

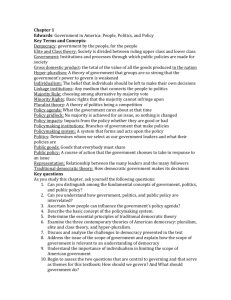

Citizens, Politicians and the Media: Evaluating Democratic Processes SF2222; Spring 2011; 15 högskolepoäng/15 Higher education credits University of Gothenburg Bengt Johansson, Department of Journalism, Media and Communication 031-786 4984; bengt.johansson@jmg.gu.se Elin Naurin, Department of Political Science 031-786 1243; elin.naurin@pol.gu.se Administrator: Christina Petterson, 031-786 11 93; Christina.Petterson@gu.se Course website: https://gul.gu.se/courseId/37640/content.do?id=15032712 General information (version 2011-03-07) The schedule and all other information is available from the course web site (GUL SF2222). Any changes, additions, or other messages will be posted there, as well as e-mailed to participants’ GU-addresses. In other words, please check your GU-addresses and the web site regularly during the course. Substance A major goal of democracy is to realize “the will of the people.” But how should this be achieved? How is it achieved in reality? To find out, this course zooms in on three groups of actors: citizens, politicians, and the mass media. We consider research on voting behaviour, political psychology, political participation, and political representation, the impact of the mass media, political journalism and news management. What does this research tell us about these actors and how they interact under different circumstances? How do these actors, and the relations between them, live up to requirements imposed by different models of democracy? What do research results reveal about how various democratic values can be realized? Specific aims Specifically, the course has three aims: 1. To develop your knowledge of, and ability to critically evaluate, research on voting behaviour, public opinion, political psychology, political participation, political representation, the impact of the mass media, political journalism and news management. 2. To develop your ability to analyze democratic issues in the light of empirical research. To what extent does current democratic processes live up to the ideals and assumptions of normative models of democracy. And how could democracy be improved: which 1 democratic reforms seem promising given that we want to realize certain democratic models and values? 3. To develop the participants’ academic writing and oral presentation skills. The course is shaped by the lecturers as well as by students themselves. About two-thirds of the teaching hours are traditional one-way lectures. About one-third is spent on seminars where participants and lecturers discuss issues raised in the literature. The idea is to supplement the worldview of the lecturers with the knowledge and creativity of the participants. This should stimulate questions and answers that would otherwise not have seen the light of day. As explained in more detail below, grading is based on: (1) a written exam halfway into the course, (2) an oral presentation where students work together in groups of two or three (“the Day of Creativity”), (3) a shorter oral seminar presentation during the second half of the course, the contents of which is also reported in a short memo (1-3 pages), (4) a written review essay of roughly 3,000-5,000 words, presented and defended in an oral presentation. (5) active participation in the final “breakfast reflection”. Organization The theoretical and empirical content of the course are described in detail below where the lectures are outlined. The pedagogical idea of the course can be summarized in five headlines: Introduction and welcome – getting to know the subject and each other The course kicks off with an introduction and description of the aim of the course. Emphasis is put on defining the general goals of the course, as well as on presenting the participating students. The students will meet several different lecturers during the ten weeks of the course. To make the most of these contacts, it is important that the group quickly gets into a talkative and open atmosphere. Internationally competitive university courses put great emphasis on personal contacts both between students and between students and lecturers. It is our aim to create an environment where students feel relaxed and inspired and where they help each other in their studies. Study hard – learning how others think The introduction is followed by a series of lectures describing theories and results generated by a number of related research fields. The aim of this part of the course is that the students will get a good overview of what research has shown so far. This knowledge will be tested with the help of a written exam about halfway through the course. The exam will be based on the lectures and literature covered to this point. The students are encouraged to systematically create their own summaries of each lecture and corresponding literature when studying. Such summaries are sometimes called portfolios and become a concrete result of the course for the students to bring with them. The students are also encouraged to study together, discussing interpretations of the literature. The exam covers the general findings and arguments, not details. It is examined as pass (G), well pass (VG) or not pass (U). Creativity – thinking outside the box The hard work studying others ideas needs to be combined with encouragements to think independently. During the preparation for the written exam, a one day exercise on creativity is 2 therefore built-in. The day is described in the document “Instructions for the Day of Creativity”. It is examined as pass (G) or not pass (U) via a short oral group presentation and active participation in the seminars. Writing and presenting- creating something of your own After the exam, it’s time to choose an individual book package (see below). This package, together with other relevant course literature, forms the basis of a review essay and a corresponding oral presentation by the end of the course. Instructions are found by the end of this document. The job with the review essay means that you will spend many hours working on your own. Too much reading and writing in solitude is boring and counterproductive. So parallel to the work on the review essay, there are lectures that present research on specific or current topics. Students are expected to prepare one question each to the lectures where articles are mentioned as recommended readings (see description below). Two discussion seminars are arranged to help in the process of writing the review essay. During these seminars each student contributes with one oral presentation based on a topic related to the review essay. A short PM lining up the important points of the presentation is turned in to the teacher. The students choose what topic they wish to talk about, and also which of the two seminar days they wish to do their presentation. They participate in both seminars with comments and questions to their fellow student colleagues. Reflection – what have I learned? What more do I want to learn? Self evaluation is a pedagogical tool that is used to promote reflection among both students and lecturers. This course ends with a “breakfast reflection” where students and the responsible lecturers together define what the students have learned during the course. Before the meeting, the students look back at the course, read their portfolios & the review essay and summarize in three points what they have learned, and in three other points what more they want to learn. The lecturers do the same. Everyone is free to bring their own breakfast. Active participation in the discussion means you pass this part of the course. 3 Lectures and literature We now turn to short descriptions of the substantive lectures together with their respective reading lists. The literature consists of the three text books listed below (available from the book store), together with a large number of articles from scientific journals and books. The latter can be accessed by GU students via the library’s electronic resources, unless otherwise stated. In some cases, paper handouts are provided, or files uploaded by lecturers. Weale, Albert. 2007. Democracy. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave. Dalton, Russell J. 2008, fifth edition. Citizen Politics. Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Washington DC: CQ Press. Stanyer, James. 2007. Modern Political Communication. Mediated Politics in Uncertain Times. Cambridge: Polity Press. 4 INTRODUCTION AND WELCOME Monday 28 March 8.15-10.00 B110 Elin Naurin & Bengt Johansson Abstract: This first meeting includes practical information and serves as a more formal introduction of the course. We also aim to get to know each other a bit more. __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 1. DEMOCRATIC THEORY AND EMPIRICAL RESEARCH Monday 28 March 10:15—12:00 B110 Elin Naurin Abstract: This lecture introduces models of democracy that can be used for analyzing empirical research on citizens, politicians and the media”? How can an analysis of the democratic relevance of empirical research on this subject be organized? And by the way, what do we mean by “Democracy”? What values should ideally be realized in a well-functioning democracy? Berelson, Bernard. 1952. "Democratic Theory and Public Opinion." Public Opinion Quarterly 16:313-330. Weale, Albert. 2007. Democracy. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave. __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 2. THE QUALITY OF PUBLIC OPINION Tuesday 29 March 10:15—12:00 B110 Peter Esaiasson Abstract: What do citizens know about politics? To what extent and under which circumstances does “the will of the people” exist at all? Are there ways in which uninformed citizens can still make informed choices? Would highly and equally informed electorates hold different policy and party preferences? Dalton. Citizen Politics. Chapters 1 and 2. Converse, Philip E. “The nature of belief systems in mass publics.” 1964. Reprinted in Critical Review 2006, Vol 18:1- 74. Luskin, Robert C. 2002. "From Denial to Extenuation (and Finally Beyond): Political Sophistication and Citizen Performance." Pp. 217-252 in Thinking About Political Psychology, edited by James H. Kuklinski. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Available via GUNDA’s “e-books”.) Lupia, Arthur. 1994. "Shortcuts versus Encyklopedias: Information and Voting Behavior in California Insurance Reform Elections." American Political Science Review 88:63-76. Lodge, Milton, Marco R Steenbergen, and Shawn Brau. 1995. "The Responsive Voter: Campaign Information and the Dynamics of Candidate Evaluation." American Political Science Review 89:309-326. Oscarsson, Henrik. 2007. "A Matter of Fact? Knowledge Effects on the Vote in Swedish General Elections, 1985–2002 " Scandinavian Political Studies 30:301-22. __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 3 MEDIA, DEMOCRACY AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE Tuesday 29 March 14:15—16:00 B110 Bengt Johansson 5 Abstract: What role should the media play in a democracy? Should the media only supply voters with information or should perhaps the media also engage the electorate? And what is “quality” when it comes to journalism and its relation to democracy? Since there are a number of definitions of democracy, this lecture focuses on the way quality of news and media content can be related to different models of democracy. Stanyer Chapters 4 and 5, Introduction and Conclusion Marx Ferree, Myra; Gamson, William A, Gerhards, Jurgen & Rucht, Dieter. 2002 “Four models of the public sphere in modern democracies. Theory and Society 31:289-234 Asp, Kent. (2007) “Fairness, informativeness, and scrutiny. The role of news media in democracy”. Nordicom review vol 28:31-50 . Zaller, John (2003) “A new standard of news quality : Burglar alarms for the monitorial citizen”. Political Communication 20:2 109-130 Strömbäck, Jesper. (2005) “In Search of a Standard: four models of democracy and their normative implications for journalism”. Journalism Studies, Volume 6, Number 3, 2005, pp. 331!345 __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 4 AN INTRODUCTION TO RESEARCH ON PARTY CHOICE Thursday 31 March 10:15—12:00 B225 Henrik Oscarsson Abstract: This lecture will introduce three classic traditions in research on voting behaviour and party choice: the sociological model, the social psychological model and the economic-rational model. The history and central concepts of these research traditions will be discussed as well as how these models of voting behaviour relates to different democratic ideals and models of democracy. Dalton. Citizen Politics. Chapters 7-10. Stokes, Donald E. 1963. "Spatial Models of Party Competition." American Political Science Review 57:368-377. Carmines, Edward G, and James A. Stimson. 1980. "The Two Faces of Issue Voting." American Political Science Review 74:78-91. Green, Jane 2007. "When Voters and Parties Agree: Valence Issues and Party Competition " Political Studies 55:629-655. __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 5 RETROSPECTIVE VOTING AND ACCOUNTABILITY Thursday 31 March 13:15—15:00 B225 Henrik Oscarsson Abstract: Is retrospective electoral accountability a feasible alternative for maintaining the electoral connection in democratic political systems? And is deciding whether to support the government or not based on its performance during the past incumbency period an easy option for citizens? Different institutional and contextual factors that facilitate or hamper retrospective electoral accountability will be discussed in this lecture. Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Martin Paldam. 2000. "Economic Voting: An introduction." Electoral Studies 19:113121. Anderson, Christopher J. 2007. "The End of Economic Voting? Contingency Dilemmas and the Limits of Democratic Accountability." Annual Review of Political Science 10:271-96. Powell, G. Bingham, and Guy D. Whitten. 1993. "A Cross-national Analysis of Economic Voting: Taking Account of the Political Context." American Journal of Political Science 87:391-414. Taylor, Michaell A. 2000. "Channeling Frustrations: Institutions, Economic Fluctuations, and Political Behavior." European Journal of Political Research 38:95-134. 6 Sanders, David 2000. "The real economy and the perceived economy in popularity functions: how much do voters need to know?: A study of British data, 1974–97." Electoral Studies 19:275-294. Kumlin, Staffan. 2009. “Informed Electoral Accountability and the Welfare State: Experimental and Real-World Evidence” (available at www.pol.gu.se/personal/staffankumlin) Butt, Sarah. 2006. "How Voters Evaluate Economic Competence: A Comparison between Parties In and Out of Power " Political Studies 54:743-766. Carlsen, Fredrik. 2000. “Unemployment, inflation and government popularity – are there partisan effects?” Electoral Studies 19:141-150. Lecture 6. POLITICAL PARTICIPATION Friday 1 April 10:15--12:00 B225 Peter Esaiasson Abstract: This lecture takes a closer look at the causes and motivations underlying different types of political participation. This includes large-scale collective activities such as electoral participation, party activities, as well as more individual modes of exercising influence. The key question is why some people participate in political processes whereas others don’t. Should we, and can we, avoid a concentration of political influence to an educated, materially privileged, and perhaps ethnically homogenous middle class Dalton. Citizen Politics. Chapters 3 and 4. Stanyer Chapters 6 and 7 Lijphart, Arend. 1997. "Unequal Participation: Democracy's Unresolved Dilemma." American Political Science Review 91:114. Blais, André 2006. "What Affects Voter Turnout?" Annual Review of Political Science 9:111–125. Adman, Per 2008. "Does Workplace Experience Enhance Political Participation? A Critical Test of a Venerable Hypothesis." Political Behavior. 30:1. Lecture 7. CITIZENSHIP AND MEDIATED PUBLIC PARTICIPATION Friday 1 April 13:15-15:00 B225 GUEST: Karin Wahl-Jorgensen, University of Cardiff DAY OF CREATIVITY: Monday 4 April 8-16 B228 and Department of Journalism, Media and Mass Communication Elin Naurin, Patrik Öhberg & Bengt Johansson See the document “Instructions for the Day of Creativity”. The hard work studying others ideas needs to be combined with encouragements to think independently. During the preparation for the written exam, a one day exercise on creativity is therefore built-in. The students are divided into groups of two or three and spend the day designing a creative research proposal. The day is ended with a short oral presentation commented on by the rest of the group and the teacher. 8-9 9-10 10-10.30 10.30-12 12-14 14-16 Lecture in B228 Now you know the talk – but can you do the walk…? Fika at the Department of Journalism, Media and Mass Communication Ideas tested on the rest of the group. Preparations Presentations in B228 7 OPTIONAL: CHALLENGES OF DEMOCRACY Thursday 7 April 14-17 CG-salen Handelshögskolan (byggnad F vån 4) For Swedish speaking participants: SYMPOSIUM: DEMOKRATINS UTMANINGAR Frågor om demokrati har under senare tid ställts på sin spets: Internationellt har händelserna i Nordafrika visat på betydelsen av sociala medier och folkliga protester för omvandlingar av oönskade politiska system. Nationellt har brister i valsystemet lett till att nyval ska hållas i Örebro och Västra Götaland. Med Sverigedemokraternas inträde i riksdagen har vi fått ett nytt politiskt landskap. Var med och diskutera var forskning om opinion och demokrati befinner sig vid Göteborgs universitet och hur den bör utvecklas i framtiden. Alla är varmt välkomna! Anmäl dig senast 1 april till emma.andersson@pol.gu.se Participants: Lena Wängnerud, Peter Esaiasson, Abby Peterson, Anders Biel, Bengt Johansson, Göran Rosenberg, Helena Lindholm Schultz, Christian Munthe. __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 8. MEDIATIZATION –THE IMPACT OF MASSMEDIA ON POLITICS Friday 8 April 10:15—12:00 B225 Bengt Johansson Abstract: The concept of mediatization is one of the most used in contemporary research on media impact on politics. But what is mediatization? What are the origins of the concept, definitions and critique? Is there research showing any proof of a growing mediatization of politics? Hjarvard, Stig (2008): The Mediatization of Society. Nordicom-reveiew. Meyer, Christoph O. (2009): Does European Union politics become mediatized? The case of the European Commission. Journal of European Public Policy 16:7 October 2009: 1047–1064 Strömbäck, Jesper (2008). Four Phases of Mediatization. An Analysis of the Mediatization of Politics. International Journal of Press/Politics, vol. 13(3), pp. 228-246. __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 9 POLITICAL REPRESENTATION Wednesday 13 April 10:15—12:00 B228 Elin Naurin Abstract: This lecture focuses on the concept of representation. We start with Hanna Pitkin's classical definition which puts "acting in the interest of the people" to the foreground of analysis. During the second hour we discuss what representation means in the context of contemporary European multi-party systems. The responsible party model is introduced. 8 Dalton. Citizen Politics. Chapter 11. Weale: Democrcy Chapter 6 Powell, G. Bingham 2004. "Political Representation in Comparative Politics." Annual Review of Political Science 7:273–96. Holmberg, Sören. 1989. "Political Representation in Sweden." Scandinavian Political Studies 12:1–36. Huber, John D., and G. Bingham Powell. 1994. "Congruence between Citizens and Policymakers in Two Visions of Liberal Democracy." World Politics 46:291-326. Blais, André, and Marc André Bodet 2006. "Does Proportional Representation Foster Closer Congruence Between Citizens and Policy Makers? ." Comparative Political Studies 39:1243-1262. Royed, Terry. 1996. "Testing the Mandate Model in Britain and the United States: Evidence from the Reagan and Thatcher Eras." British Journal of Political Science 26. Mansergh, Lucy & Robert Thomson (2007); “Election Pledges, Party Competition, and Policymaking”, Comparative Politics, Volume 39, Number 3, April 2007. __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 10 WOMEN IN PARLIAMENTS: DESCRIPTIVE AND SUBSTANTIVE REPRESENTATION Thursday 14 April 8:15—10:00 B110 Lena Wängnerud Abstract: This lecture focuses on variations in the number of women elected to national parliaments in the world (descriptive representation), and on effects of women's presence in parliaments (substantive representation). The theory of the politics of presence (Phillips 1995) is introduced, which provides reasons for expecting a link between descriptive and substantive representation. We discuss an alternative approach which emphasizes the importance of "feminist awareness" among parliamentarians instead of sex/gender in its pure or basic sense. The issue of other social background characteristics, beside gender, is also raised. Wängnerud, Lena (2009) Women in Parliaments: Descriptive and Substantive Representation. Annual Review of Political Science 12:51-59. Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie A, and Mishler, William. 2005. "An Integrated Model of Women's Representation." Journal of Politics, Vol. 67, No. 2, pp. 407-428. Stanyer Chapter 3 Lecture 11 NEWS MANAGEMENT AND POLITICAL MARKETING Friday 15 April 10:15—12:00 B225 Bengt Johansson Abstract: This lecture focuses on the strategies of political parties during election campaigns. We will start outlining the historical trends of campaigning and end up with the present situation were campaigns tend to become more and more professionalized. In present research there is a debate about how professionalization of campaigning should be understood and its relation to concepts like “Americanization” and “Globalization”. Stanyer Chapters 1 and 2 Peterson et al 2007 “The parties’ campaign in Peterson et al Media and elections in Sweden http://www.sns.se/document/dr_2006_english_web.pdf Strömbäck, Jesper “Political Marketing and Professionalized Campaigning: A Conceptual Analysis, in Journal of Political Marketing Vol. 6(2/3) 2007 Lees-Marshment, Jennifer (2001) “The marriage of politics and marketing”. Political Studies. Vol 49: 692-713 __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 12 DOES PUBLIC OPINION AFFECT PUBLIC POLICY? Monday 18 April 10:15—12:00 B228 Elin Naurin 9 Abstract: This lecture focuses on empirical research that study effects of public opinion on public policy. Issues raised are under what circumstances and in which type of issues public opinion might have an effect. The relationship between public opinion, parliament and public policy is highlighted. Wlezien, Christopher, and Stuart N. Soroka. 2007. "The Relationship between Public Opinion and Policy." Pp. 799-817 in The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, edited by Russel J Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 8 (To be distributed by Elin Naurin.) Burstein, Paul. 2003. "The Impact of Public Opinion on Public Policy: A Review and an Agenda." Political Research Quarterly 56 29-40. Brettschneider, Frank. 1996. "Public Opinion and Parliamentary Action: Responsiveness of the German Bundestag in Comparative Perspective." International Journal of Public Opinion Research 8:292-311. Holmberg, Sören. 1997. "Dynamic Opinion Representation." Scandinavian Political Studies 20:265-283. Schmitt, Hermann, and Jacques Thomassen. 2000. "Dynamic Representation: The Case of European Integration." European Union Politics 1:318-339. __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 13. DEMOCRATIC REPRESENTATION UNDER PRESSURE: THE AFRICAN CONTEXT Tuesday 19 April 10:15—12:00 B009 Staffan I. Lindberg Abstract: This lecture takes the theoretical concept of democratic representation to the African context. We focus on empirical research studying the relationship between representatives and voters in systems under pressure of corruption, poverty and lack of individual rights. We talk about the challenges that the African context offer to the traditional models of representation, such as the Responsible Party Model: In what way do we need to develop our models of representation in order to understand African democracies? What is the role of democratic elections in these countries? How is public opinion shaped? What is a democratic mandate? Bratton, Michael. 2007. “Formal versus Informal Institutions in Africa.” Journal of Democracy 18(3): 96-110. Dunning, Thad and Lauren Harrison. 2010. “Cross-Cutting Cleavages and Ethnic Voting: An Experimental Study of Cousinage in Mali.” American Political Science Review 104(1): 21/39. Ekeh, Peter P. 1975. “Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa: A theoretical Statement.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 17(1):91-112. Lindberg, Staffan I. 2010. “ Accountability Pressures Do MPs in Africa Face and How Do They Respond? Evidence from Ghana” Journal of Modern African Studies 48(1): 117-142. For the interested, as added reading (not compulsory): Bratton, Michael and Nicolas van de Walle. 1994. “Neopatrimonial Regimes and Political Transitions in Africa.” World Politics 46(4): 453-489. Erdman, Gero. 2007. “The Cleavage Model, Ethnicity and Voter Alignment in Africa: Conceptual and Methodological Problems Revisited.” GIGA Working Papers. No. 63. Lindberg, Staffan I. and Minion K. C. Morrison. 2008. “Are African Voters Really Ethnic or Clientelistic?: Survey Evidence from Ghana.” Political Science Quarterly 123(1): 95-122. Lindberg, Staffan I. and Keith R. Weghorst. 2010. “Are Swing Voters Instruments of Democracy or Farmers of Clientelism? Evidence from Ghana”. Working Paper 2010:17 University of Gothenburg: Quality of Government Institute. Lindberg, Staffan I. 2003. “It’s Our Time to ‘Chop’: Do Elections in Africa Feed Neopatrimonialism rather than Counter-Act It?” Democratization 14(2): 121-140. Posner, Daniel N. and David J. Simon. 2002. “Economic Conditions and Incumbent Support in Africa’s New Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies 35 (3): 313-336. Wantchekon, Leonard. 2003. “Clientelism and Voting Behavior: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Benin.” World Politics 55:399-422. 10 __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 14. SELF-INTEREST, SOCIAL JUSTICE AND PUBLIC DELIBERATION Wednesday 28 April 10:15—12:00 A110 Peter Esaiasson Abstract: To what extent is public opinion guided by self-interested considerations? The typical answer from opinion research is that self-interest plays a surprisingly limited role in opinion formation. In this lecture we will discuss factors that moderate the importance of self-interest, and we will also introduce the rival perspectives of social justice research and research on public deliberation. Sears, David O., Richard R. Lau, Tom R. Tyler, and Harris M. Jr. Allen. 1980. "Self-interest vs. Symbolic Politics in Policy Attitudes and Presidential Voting." American Political Science Review 74:670-684. Sears, David O., and Carolyn L. Funk. 1990. "The Limited Effect of Economic Self-Interest on the Political Attitudes of the Mass Public." Journal of Behavioral Economics 19:247-271. (Only in ugly html format. You may want to copy the paper version in the library.) Delli Carpini, Micheal X., Fay Lomax. Cook, and and Lawrence R. Jacobs. 2004. "Public Deliberation, Discursive Participation, and Citizen Engagement: A Review of the Empirical Literature." Annual Review of Political Science 7:315-44. Luskin, Robert P., James S. Fishkin, and Roger Jowell. 2002. "Considered Opinions: Deliberative Polling in Britain." British Journal of Political Science 32:455-487. __________________________________________________________________________ Lecture 15. MODERNIZATION AND CONTEXT: COMING TO GRIPS WITH ELECTORAL CHANGE Thursday 28 April 13:15—15:00 A110 Henrik Oscarsson Abstract: Soon, universal suffrage will have existed for 100 years in some democratic countries. During this period a process of societal modernization has occurred. What is the impact on electoral behaviour of for example the economic development, the process of secularization, the increased impact of mass media, the rise in educational level and the higher social and geographical mobility that have taken place in many advanced industrialized democracies? To what extent have modernization processes resulted in an individualized society and to what extent are old values and conflicts still relevant for understanding electoral behaviour? Abstract: Dalton. Citizen Politics. Chapters 5-10, and 12. Thomassen, Jacques. 2005. "Modernization or Politics?" Pp. 254-266 in The European Voter: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies, edited by Jacques Thomassen. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (To be distributed by Henrik Oscarsson.) Green-Pedersen, Christopher. 2007. "The Growing Importance of Issue Competition: The Changing Nature of Party Competition in Western Europe." Political Studies 55:607-628. WRITTEN EXAM Tuesday 3 May 14.30-18.30 11 WORK WITH REVIEW ESSAY STARTS Wednesday 4 May Students start working with their review essay. Book packages are chosen before this date on GUL. Books are picked up at the lecturers’ rooms. Lecture 16. MEDIA CAMPAIGNS – NEW CHALLENGES Thursday 5 May 10:15—12:00 D206 Bengt Johansson Abstact: Political marketing is a growing field in political communication. A number of scholars have pointed out the growing tendency to use PR-consultants, polls and other strategic campaign tactics during elections campaigns. In the light of a changing media environment new channels of communication (Internet and mobile phones) have been added to old forms of campaign communication. This lecture focus on how these new technologies might change campaign cultures and also points out trends in election campaigns. Patrick A. Stewart and James N. Schubert: Taking the "Low Road" with Subliminal Advertisements. A Study Testing the Effect of Precognitive Prime "RATS in a 2000 Presidential Advertisement”. The International Journal of Press/Politics 2006; 11; 103 James N. Druckman; Martin J. Kifer; Michael Parkin Timeless Strategy Meets New Medium: Going Negative on Congressional Campaign Web Sites, 2002–2006, Political Communication 2010:4 Pages 88 – 103 Lauren Feldman; Dannagal Goldthwaite Young Late-Night Comedy as a Gateway to Traditional News: An Analysis of Time Trends in News Attention Among LateNight Comedy Viewers During the 2004 Presidential Primaries 2008:4 Pages 401 – 422 Students are expected to prepare one question each for the lecturer based on the articles above. Seminar 1 Monday 9 May 10:15-12:00 B225 Bengt Johansson Discussion seminar to help in the process of writing the review essay. During this or the next seminar each student contributes with one oral presentation based on a topic related to the review essay. A short PM lining up the important points of the presentation is turned in to the teacher. The students choose what topic they wish to talk about, and also if they want to present during this seminar, or during the next seminar. All students participate in both seminar 1 and seminar 2 with questions and comments to their fellow student colleagues. Seminar 2 Wednesday 11 May 10:15-12:00 A010 Elin Naurin 12 Discussion seminar to help in the process of writing the review essay. During this or the above seminar each student contributes with one oral presentation based on a topic related to the review essay. A short PM lining up the important points of the presentation is turned in to the teacher. The students choose what topic they wish to talk about, and also if they want to present during this seminar, or during the above seminar. All students participate in both seminar 1 and seminar 2 with questions and comments to their fellow student colleagues. LECTURE 17. MEDIATIZATION IN GERMAN POLITICS Friday 20 May 10:15-12:00 A110 Guest: Dr Reimar Zeh, University Erlangen-Nurnberg. LECTURE 18. EXPERIMENTING WITH VOTERS: EMBARKING ON NEW FIELDS IN OPINION STUDIES Wednesday 25 May 10:15-12:00 A110 Johan Martinsson Abstract: This lecture takes the students to the edge of voter studies by introducing the research that dares to embark on experimental designs – one of the most rapidly growing fields in contemporary political science. Recent advances in electoral studies are presented and the students will get an overview of the advantages as well as of the difficulties and limitations that face this approach. Is experimental research the future for studies of voter behaviour and public opinion formation? Special focus is given to experimental research on the concept of “issue ownership”. Can political actors benefit from being perceived to "own" issues, and how can such a situation be achieved or maintained by political parties? McDermott, Rose. 2002. “Experimental Methods in Political Science,” Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 5(June):31-61. Druckman, James, Donald Green, James Kuklinski, and Arthur Lupia. (2006). “The Growth and Development of Experimental Research in Political Science,” American Political Science Review 100:627-635. Dahlberg, S., & Martinsson, J. (2011 forthcoming) ”Issue Ownership – Who can steal it? and How?” Paper presented at Midwest political science association meeting, Chicago, April 2011. Posted on GUL one week before the lecture. Holian, D. B. (2004) “He’s Stealing my Issues! Clinton’s Crime Rhetoric and the Dynamics of Issue Ownership” Students are expected to prepare one question each for the lecturer based on the articles above. FINAL Seminar Monday 30 May 10:15-17:00 A110 and B110 Bengt Johansson & Elin Naurin OPTIONAL: LUNCH SEMINAR AT THE QUALITY OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTE Tuesday 31 May 12.00-13.00 Room: Skagen Susan Stokes If your interested to go, please notice Elin Naurin 13 BREAKFAST REFLECTION Wednesday 1 June 8:15-10:00 B225 Elin Naurin & Bengt Johansson 14 The review essay The review essay is based on an individually chosen “book package” (see below), usually consisting of two related books, together with relevant course literature. The essay has several purposes: First, it is the single most important basis for your grade. Second, because all review essays are distributed among participants, each will walk away from the course with a library of accessible introductions to a range of research fields. We anticipate that the average review essay will be about 3,000 words. Essays longer than 5,000 words will not be accepted. More exactly, a good review essay should do three things: Summarize the research: Tell us about the most important theoretical ideas, models, and arguments, as well as about the most important empirical results. Criticize the research: Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the research. Are the theoretical ideas and empirical methods reasonable and sound? Do you buy the conclusions? Why/Why not? Analyze the democratic relevance of the research: What does this research say about the extent to which current democratic processes live up to assumptions made by various models of democracy? What does this research suggest about how democratic processes could be improved, given that we want to realize certain democratic models and values? Notwithstanding these compulsory questions, you are free to organize your essay anyway you see fit. It is not important in what order or manner you answer the questions. Try to discover the structure that works best for “the story” you want to tell. Use your creativity and have fun! Try to be coherent in the sense that you discuss roughly the same ideas and research results all through the essay. For example, don’t change the topic completely when you come to the third question. To achieve this you must be selective. We don’t want you to summarize, criticize, and analyze the democratic relevance of every page in the literature. On the contrary, it is an analytical task for you to identify a nucleus of important ideas and research results, which will make for a coherent and readable essay. It is often the case that there are several potential review essays to be written based on a given book package, but that you choose to focus on one particularly interesting one. Also, be prepared that whereas one book may focus entirely on topics a, b, and c, the second book may focus on topics b, c, and d. In this situation, you should concentrate on the common denominators b and c. Further, you need to decide whether you can integrate both topics b and c into your essay, or whether you think it is enough to concentrate on just either b or c. Finally, for some book packages it is perhaps unusually obvious what “the” topic is and which research results could be brought up in the answers to the questions. However, many book packages provide several topics that could make for a coherent review essay. Almost inevitably, not only the book package but also some of the course literature will be relevant to your review essay. Therefore, we expect you to refer to this literature where you think it is relevant and improves the essay. We are generally impressed if you succeed in connecting your topic to parts of the course literature in this way. (Of course, we are not impressed by superficial “namedropping” doing little to improve the discussion.) 15 Don’t forget to include a list of references at the end of your essay, so that others can comfortably read and use it in the future. Also, give your review essay a substantive title (rather than calling it “review essay”). Review essays will be checked with appropriate software to ensure that they are in fact the result of original work. The seminars Review essay seminars: During review essay seminars on the final day, we have roughly 10 minutes for the presentation and 10 minutes for discussion. The students are divided into two groups that follow each other during the day. Seminar 1 & 2 Presentations during discussion seminars are to be seen as help for the final seminar. The talk is 5-10 minutes and the memo is 2-3 pages and should hint at answers to the same questions as those relevant to the review essay. The groups are spread evenly via GUL between Seminar 1 and Seminar 2. E-mail word/rtf files to Bengt or Elin respectively. Course requirements and grading The following requirements apply for passing the course: Passing the written exam. A decent review essay. A decent oral review essay presentation on the final day. Giving one presentation during discussion seminars (also to be reported in short memo). Actively participating in the Day of Creativity by giving an oral group presentation. Actively participating in the breakfast reflection What does decent mean? Here are the dimensions along which we evaluate your written and oral efforts: How ambitious is this effort in terms of workload and intellectual scope? How grounded in the literature is it? How coherent, consequent, and structured is it? How original and independent is it? (i.e., to what extent does it only repeat points made in the literature, and to what extent does it also use the literature to develop points that are not clearly articulated in literature?) How persuasive is it when it comes to teasing out the democratic relevance and implications of empirical research? The written exam, the review essay, the oral presentations, and seminar performance all affect the final grade, but the essay is the single most important element. The second most important element is the written exam. There are two roads to VG (pass with distinction): Written exam VG + Review essay VG + everything else G Or Review essay VG + close to VG in written exam + important contributions to discussion in seminars/memo 16 Late delivery of the review essay will affect your grade negatively. Finally, we expect you to return any literature that you have borrowed. (In fact, you will not get a grade until you do...). And please, please – with sugar on top – don’t take notes in our books. 17 Book packages Each participant is to choose one of the “book packages” listed below. This cannot be done until after the written exam. The list of packages may change somewhat, depending on the number and background of participants. The course will be better if everyone chooses a unique package. To achieve this, we strongly encourage you to make a rather long mental list of packages that could be of interest to you, rather than keeping your eyes fixed on a single one. We flip a coin if several participants nevertheless want the same book package. Most packages consist of two books, but some of one book only. When this occurs, it is usually because we consider that book unusually demanding in terms of intellectual scope, methodology, and perhaps sheer size. Participants will not need to buy any book packages. They can be borrowed from us. Review essays are distributed among the participants, which means each participant will walk away from the course with a library of accessible introductions to a wide range of research fields. Package 1: Political knowledge and accountability Delli Carpini, Michael, and Scott Keeter. 1996. What Americans Know About Politics and Why it Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press. Hutchings, Vincent L. 2003. Public Opinion and Democratic Accountability: How Citizens Learn about Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Package 2: The impact of identity and ethnicity on social solidarity Berg, Linda. 2007. Multi-level Europeans. The Influence of Territorial Attachments on Political Trust and Welfare Attitudes". Göteborg Studies in Politics. Crepaz, Markus M.L. 2007. Trust beyond Borders. Immigration, the Welfare State, and Identity in Modern Societies. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Package 3: The miracle of aggregation? Page, Benjamin I., and Robert Y. Shapiro. 1992. The Rational Public. Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Althaus, Scott L. 2003. Collective Preferences in Democratic Politics: Opinion Surveys and the Will of the People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Package 4: The nature and origins of political preferences Zaller, John R. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Granberg, Donald, and Sören Holmberg. 1988. The Political System Matters. Social Psychology and Voting Behavior in Sweden and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Package 5: Personal experiences vs. the mass media as political information sources Mutz, Diana C. 1998. Impersonal Influence. How Perceptions of Mass Collectives Affect Political Attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kumlin, Staffan. 2004. The Personal and the Political: How Personal Welfare State Experiences Affect Political Trust and Ideology. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan. 18 Package 6: Shortcuts and deliberation Popkin, Samuel L. 1991. The Reasoning Voter: Communication and Persuasion in Presidential Campaigns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Fishkin, James S. 1995. The Voice of the People. Public Opinion and Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press. Package 7: Political representation and opinion formation in the European Union Schmitt, Hermann, and Jacques Thomassen (Eds.). 1999. Political Representation and Legitimacy in the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gabel, Matthew J. 1998. Interests and Integration: Market Liberalization, Public Opinion and European Union. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigian University Press. Package 8: Change and causality in political participation Norris, Pippa. 2002. Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism. Oxford: Cambridge University Press. Goul Andersen, Jørgen, and Jens Hoff. 2001. Democracy and Citizenship in Scandinavia. New York: Palgrave. Package 9: Gender and participation: Why are women less participating? Burns, Nancy, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Sidney Verba. 2001. The Private Roots of Public Action: Gender, Equality, and Political Participation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Package 10: Referendums Butler, David, and Austin Ranney (Eds.). 1994. Referendums around the World: The Growing Use of Direct Democracy. London: Macmillan. Jenssen, Anders Todal, Pertti Pesonen, and Mikael Gilljam (Eds.). 1998. To Join or Not to Join. Three Nordic Referendums on Membership in the European Union. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press. Package 11: Mobilizing and stimulating participation in the US Rosenstone, Steven J., and John Mark Hansen. 2004. Mobilization, Participation and Democracy in America. Harlow: Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers. Campbell, Andrea. 2005. How Policies Make Citizens: Senior Political Activism and the American Welfare State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Package 12: The impact of election campaigns: comparing the past and the present Lazarsfeld, Paul F., Bernhard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet. 1944. The People's Choice. How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. New York: Columbia University Press. Norris, Pippa, John Curtice, David Sanders, Margaret Scammell, and Holli Semetko. 1999. On Message: Communicating the Campaign. London: Sage. Package 13: Agenda-setting and framing Iyengar, Shanto, and Donald R. Kinder. 1987. News that Matters. Television and American Opinion. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Iyengar, Shanto. 1991. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Package 14: Evaluating modern mass media Capella, Joseph N., and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. 1997. Spiral of Cynicism. The Press and the Public Good. New York: Oxford University Press. Norris, Pippa. 2000. A Virtous Circle: Political Communications in Postindustrial Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Package 15: Political Trust: Causes and Effects Norris, Pippa (Ed.). 1999. Critical Citizens. Global Support for Democratic Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dalton, Russel J. 2004. Democratic Challanges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 19 Package 16: Social representation and gender Phillips, Anne. 1995. The Politics of Presence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Mateo Diaz, Mercedes. 2002. Are Women in Parliament Representing Women? Université catholique de Louvain. Package 17: The relationship between public opinion and politicians Esaiasson, Peter, and Sören Holmberg. 1996. Representation from Above. Members of Parliament and Representative Democracy in Sweden. Aldershot: Dartmouth. Manza, Jeff, Fay Lomax Cook, and Benjamin I. Page (Eds.). 2002. Navigating Public Opinion: Polls, Policy, and the Future of American Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Package 18: Keeping their promises? Naurin, Elin (2009); Promising Democracy. Parties, Citizens and Election Promises. Gothenburg Studies in Politics 118. Stokes, Susan C. 2001. Mandates and Democracy: Neoliberalism by Surprise in Latin America. Cambridge University Press. Package 19: Recent trends in research on political participation Jan van Deth, José Ramon Montero and Anders Westholm (eds). 2007. Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies. London: Routledge. Package 20: Recent trends in research on accountability and economic voting Maravall, José María, and Ignacio Sánchez-Cuenca, eds. 2008. Controlling Governments: Voters, Institutions, and Accountability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. van der Brug, Wouter, Cees van der Eijk, and Mark N. Franklin. 2007. The Economy and the Vote. Economic Conditions and Elections in Fifteen Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Package 21: Global Political Campaigning Plasser; Fritz & Plasser, Gunda 2002: Global Political Campaigning: A Worldwide Analysis of Campaign Professionals and Their Practices. Praeger Publishers. Sussman, Gerald 2005: Global Electioneering: Campaign Consulting, Communications, and Corporate Financing. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. Package 22: Campaigning and New Media Technology Davis, Richard 2009: Typing Politics: The Role of Blogs in American Politics. Oxford University Press. Hendricks, John Allen & Denton, Robert E., Jr. 2010, Communicator-In-Chief: How Barack Obama Used New Media Technology to Win the White House. Lexington Books. Package 23: Avoiding politics? Eliasoph, Nina 1998: Avoiding Politics. How Americans produce apathy in everyday life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Gamson, A. William 1992. Talking Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 20