School and Teacher Effects: A Team Effort

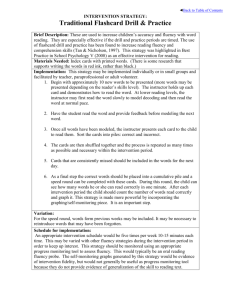

advertisement

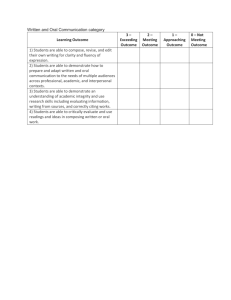

School and Teacher Effects: A Team Effort Sharon Walpole University of Delaware Michael C. McKenna University of Virginia So how’d we do last year? Let’s look at some data from the UGA external evaluator’s report Letter Naming Fluency Kindergarten - End of Year 2004-2005 80 67.5 2005-2006 74 60 40 19.2 20 16 13.3 10 0 Low Risk Some Risk At Risk Phoneme Segmentation Fluency Kindergarten - End of Year 2004-2005 100 80 70.6 2005-2006 82 60 40 21.6 20 13 7.7 5 0 Low Risk Some Risk At Risk Nonsense Word Fluency Kindergarten - End of the Year 2004-2005 100 80 2005-2006 70.7 77 60 40 20 16.5 13 12.8 10 Some Risk At Risk 0 Low Risk But WHY? Think about your most effective and your least effective kindergarten teacher. They both have the same materials. They have the same professional support system. They both have the same reading block. What is it that actually differs between the two and might lead to differences in achievement? Phoneme Segmentation Fluency First Grade - End of the Year 2004-2005 100 80 76.3 2005-2006 85 60 40 22.1 20 14 1.6 1 0 Low Risk Some Risk At Risk Nonsense Word Fluency First Grade - End of the Year 2004-2005 80 64.9 2005-2006 73 60 40 27.7 23 20 7.5 4 0 Low Risk Some Risk At Risk Oral Reading Fluency First Grade - End of the Year 2004-2005 80 64.7 2005-2006 70 60 40 22.7 20 20 12.6 10 0 Low Risk Some Risk At Risk But WHY? Think about your most effective and your least effective first-grade teacher. They both have the same materials. They have the same professional support system. They both have the same reading block. What is it that actually differs between the two and might lead to differences in achievement? Oral Reading Fluency Second Grade - End of the Year 2004-2005 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 50.8 2005-2006 56 22.3 Low Risk 21 Some Risk 26.9 24 At Risk But WHY? Think about your most effective and your least effective second-grade teacher. They both have the same materials. They have the same professional support system. They both have the same reading block. What is it that actually differs between the two and might lead to differences in achievement? Oral Reading Fluency Third Grade - End of the Year 2004-2005 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 44.5 2005-2006 51 33.9 31 21.9 Low Risk Some Risk 18 At Risk But WHY? Think about your most effective and your least effective third-grade teacher. They both have the same materials. They have the same professional support system. They both have the same reading block. What is it that actually differs between the two and might lead to differences in achievement? Lessons from School Effectiveness Literature School Differences Teacher Differences Individual Differences An LC can form judgments about teacher differences. It’s harder to judge differences at the school level because most of us lack the opportunities to make such comparisons. Nevertheless, factors at the school level can have strong effects on achievement. The better we understand them, the more we can control them through leadership. Differences among teachers have a clear impact on learning. Coaching attempts to reduce some of these differences by guiding teachers toward best practice. But what about differences among schools? Can school factors be important as well? What are some differences among kids that affect achievement? What are some differences among teachers that affect achievement? What are some differences among schools that affect achievement? Organize Your Hunches Child K 1 2 3 Teacher School Let’s look at three studies that attempted to identify school effects on reading achievement. What can we can learn from them? Beat-the-Odds Study* Design Features Looked at school and teacher factors Used measures of word readings, fluency, and retellings 14 schools, 11 of which “beat the odds” 2 teachers at each grade, and 4 children per classroom Relied on interviews, surveys, observations, and scores School factors positively correlated with growth Forging links with parents Using systematic assessment Fostering communication and collaboration *Taylor, Pearson, Clark, & Walpole, 2000. State-Level Outlier Study* Design Features 2 high-achieving, 1 low-achieving from 3 clusters: country, main street, uptown Used state tests, interviews, and observations School factors present in the high-achieving schools Strong leadership and commitment Teacher knowledge Time and opportunity for children to read Commitment of 8-10 years to the change process *Mosenthal, Lipson, Torncello, Russ, & Mekkelsen, (2004). Curriculum Effects Study* Design Features Compared 4 major reform models in first grade Each used a coach, lots of PD, and regrouping of kids 4 experienced schools in each model Measures of decoding, comprehension, vocabulary; classroom observations Comparisons All of the schools were relatively successful None of the 4 models proved best *Tivnan & Hemphill, 2005 What lessons do these studies teach? Common Characteristics 1. 2. No one curriculum or intervention model is a magical solution to student achievement problems Intense focus on the school’s goals is associated with success Assessment, communication, collaboration Leadership, vision, knowledge PD plus specific curriculum Differences From Us 1. 2. 3. These schools were successful or experienced already; we are striving to be successful and we are still new to our curricula These schools had different demographics than we do (except for the Curriculum Effects Study) These studies do not include the effects of intensive interventions Limits of Generalizability 1. 2. We can’t tell whether these characteristics are causes or characteristics of success We don’t know whether these factors “transfer” to striving schools Now let’s look at a fourth study – one with better lessons for Georgia and Reading First. GA REA Study* Question In a two-year reform initiative, what schoollevel characteristics are significantly related to first-grade achievement? Sample 22 striving schools in REA (Mean FRL = 73%) 1146 first-grade children in those schools - all children with full data *Walpole, Kaplan, & Blamey (in preparation). Data Standardized measures of decoding and comprehension, DIBELS LNF and ORF Interviews, surveys Findings All of the schools were relatively successful; ORF mean, grade 1 = 60 wcpm Standardized scores above 50th percentile! Assessment-based planning explained a small but significant amount of the variance in firstgrade achievement. This is a school factor! So What IS Assessment-Based Planning Anyway? Schools with higher achievement were rated higher on these two characteristics: The leaders made thoughtful choices to purchase commercial curriculum materials to meet school-level needs. The leaders of this project designed a comprehensive assessment system that teachers used to differentiate instruction. How Did We Find Out? We made a special rating sheet to rate the levels of implementation on all aspects of the project. We correlated those ratings with student achievement to find the ones that were most powerful. How Did We Find Out? Four variables “survived” the correlations 1. Differentiation strategies for word recognition and fluency 2. Strategy and vocabulary instruction during read-alouds 3. Careful choice of instructional materials 4. School-level design of an assessment system linked to instruction In our RF work . . . These variables correspond to: 1. Differentiated word recognition strategies for needs-based work 2. Interactive read-alouds of children’s literature (Beck + Duffy) 3. Use (or purchase) of curriculum materials based on their match with emergent achievement data 4. Selection of assessments that are really used to plan needs-based instruction How did we find out? These 4 variables were highly correlated with one another; we combined the two leadership variables and the two differentiation variables. We controlled for LNF at January of kindergarten, we controlled for SES, and assessment-based planning was still correlated with first-grade scores at the school level. What Do We Need to Learn? We need to see what variables are powerful in GARF We need to add the level of the teacher – Identify the characteristics we are targeting – Collect meaningful observational data on them to see whether they make a difference We need to use the data we have and get the data we need That’s a tall order! (But we think we can tackle it together.) From a design standpoint We are all trying to collect student data to measure the success of our programs. It does not make sense to measure program effects without measuring treatment fidelity. It does not make sense to measure treatment fidelity without observing the treatment. It does not make sense to document treatment fidelity without trying to improve it. Let’s look at the concept of “innovation configuration.” This is a way of finding out how fully we are implementing Reading First. Innovation Configuration* Full implementation The target practice is described here. Partial implementation No Implementation A practice in between (or, more likely, several different ones) is described here. A description of a practice inconsistent with the target is described here. *Hall & Hord, 2001 Context Context Learning communities Leadership Resources Process Content Data-driven Equity Evaluation Quality teaching Research-based Family involvement Design Learning Collaboration http://www.nsdc.org/standards/index.cfm Moving NSDC's Staff Development Standards into Practice: Innovation Configurations By Shirley Hord, Stephanie Hirsh & Patricia Roy Innovation Configuration for Teacher’s Professional Learning Level 4 Engages in collaborative interactions in learning teams and participates in a variety of activities that are aligned with expected improvement outcomes (e.g., collaborative lesson design, professional networks, analyzing student work, problem solving sessions, curriculum development). Innovation Configuration for Teacher’s Professional Learning Level 2 Attends workshops to gain information about new programs and receives classroom-based coaching to assist with implementation of new strategies and activities that may be aligned with expected improvement outcomes. Innovation Configuration for Teacher’s Professional Learning Level 1 Experiences a single model or inappropriate models of professional development that are not aligned with expected outcomes. Procedure for Making an IC 1. 2. 3. 4. Designer of an innovation describes ideal implementation of various components Those “ideals” are compared with “real” implementation through observation The “reals” are lined up from least like the ideal to most like the ideal Then the IC can be used for observations, and even linked to student achievement! Here are our classroom-level “ideals” for GARF so far. Physical Environment The classroom is neat, clean, and organized so that the teacher can monitor all children and accomplish whole-group and needs-based instruction and so that children can get the materials they need. Wall space is used to display student work and curriculum-related materials that children need to accomplish tasks. Curriculum Materials There is one core reading program in active use. There is physical evidence of coherence in the text-level and word-level skills and strategies targeted in the classroom environment. Texts and manipulatives for whole-group, small-group, and independent practice are organized and available. Children’s Literature There is a large classroom collection of high-quality children’s literature deliberately organized and in active use that includes narratives, information texts, and multicultural texts. Instructional Schedule There is a posted schedule inside and outside the classroom to define an organized plan for using curriculum materials for whole-group and needs-based instruction; teacher and student activities correspond to the schedule Assessment System There is an efficient system for screening, diagnosing specific instructional needs, and progress-monitoring that is visible to the teacher and informs instructional groupings, the content of small-group instruction, and a flexible intervention system. All data are used to make instruction more effective. Whole-Group Instruction Whole-group instruction is used to introduce new concepts and to model strategies. Children have multiple opportunities to participate and respond during instruction. Small-Group Instruction Small-group instruction is used to reinforce, reteach, and review. Each child spends some time in small group each day; and small-group instruction is clearly differentiated. Children have multiple opportunities to participate and respond during instruction. Independent Practice Children work alone, in small groups, or in pairs to practice skills and strategies that have been previously introduced. They read and write during independent practice. They do this with a high level of success because the teacher organizes independent practice so that it is linked to whole-group and smallgroup instruction. Management The classroom is busy and active, but focused on reading. Classroom talk is positive and academic, including challenging vocabulary. Children know how to interact during whole-class, smallgroup, and independent work time. Very little time is spent teaching new procedures. There’s a Lot We Don’t Know! Is it possible to observe with one form across all grades? How could we collect these observational data reliably and efficiently? Which of these might explain variance in student achievement? Procedure for Making an IC 1. 2. 3. 4. Designer of an innovation describes ideal implementation of various components Those “ideals” are compared with “real” implementation through observation The “reals” are lined up from least like the ideal to most like the ideal Then the IC can be used for observations, and even linked to student achievement! Professional Support System* Feedback Practice Theory Demonstration *Joyce & Showers, 2002 You be the rater! We will give you the IC that we made for the Georgia REA study. Think about your first-grade team last year. Provide us a realistic reflection on where you stood during Year 2. We will use that data to analyze the Year 2 scores and provide you an update at our next meeting! References Hall, G. & Hord, S. (2001). Implementing change: Patterns, principles, and potholes. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Joyce, B., & Showers, B. (2002). Student achievement through staff development. White Plains, NY: Longman. Mosenthal, J., Lipson, M., Torncello, S., Russ, B., & Mekkelsen, J. (2004). Contexts and practices of six schools successful in obtaining reading achievement. The Elementary School Journal, 104, 343-367. Taylor, B. M., Pearson, P. D., Clark, K. M., & Walpole, S. (2000). Effective schools and accomplished teachers: Lessons about primary-grade reading instruction in low-income schools. The Elementary School Journal, 101, 121-165. Tivnan, T., & Hemphill, L. (2005). Comparing four literacy reform models in high-poverty schools: patterns of first-grade achievement. The Elementary School Journal, 105, 419-441. Walpole, S., Kaplan, D., & Blamey, K. L. (in preparation). The effects of assessment-driven instruction on first-grade reading performance: Evidence from REA in Georgia.