Language and art - Πανεπιστήμιο Ιωαννίνων

ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ ΙΩΑΝΝΙΝΩΝ

ΑΝΟΙΚΤΑ ΑΚΑΔΗΜΑΪΚΑ ΜΑΘΗΜΑΤΑ

Εισαγωγή στην Ανθρωπολογία

της Τέχνης

Τέχνη και Κουλτούρα

(Language and art)

Διδάσκων: Καθηγητής Χρήστος Α. Δερμεντζόπουλος

Άδειες Χρήσης

Το παρόν εκπαιδευτικό υλικό υπόκειται σε άδειες

χρήσης Creative Commons.

Για εκπαιδευτικό υλικό, όπως εικόνες, που

υπόκειται σε άλλου τύπου άδειας χρήσης, η άδεια

χρήσης αναφέρεται ρητώς.

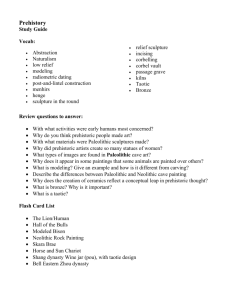

Language and art: From paleolithic art to writing

Four lectures

12th Early Fall School of Semiotics

“Semiotics of Genre”

September 10-20, 2006

Sozopol (Bulgaria)

Wolfgang Wildgen, Bremen (Germany)

3

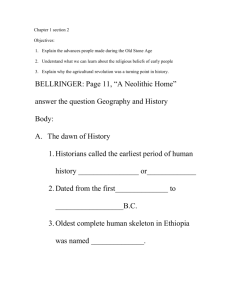

First lecture

The cognitive presuppositions of art and writing

1.1 Periods of hominid evolution leading to art and language .

1.2 The evolution of the neo-cortex as predisposition for art and language .

1.3 From animal motion to animal sign behavior .

1.4 Instrumentality in higher mammals and man .

4

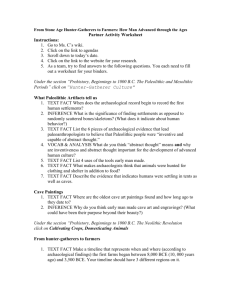

Possible evolutionary steps leading to cave art

Cave art

H. sapiens, language

Homo erectus, stone tools

Australopithecus, upright

Primates like gorillas, orang-utans and chimpanzees

10 million y. 7 million y. 2 million y. 400.000 y. 40.000

5

Evolution of the brain

HSS

Calculated brain size (in g) in relation to the evolutionary time scale in millions of years.

AF=Australopethecus Africanus, AB=

Australopethecus Boisei,

HH= Homo habilis, HE= Homo erectus, HSP=Homo sapiens praeneanderthaliensis,

HSN= Homo sapiens neanderthaliensis, HSS= Homo sapiens sapiens.

6

Overlapping of brain sizes (cf. Martin, 1998: 51) 7

Changes in the geometry of the crane

Comparison of the cavities used for articulation: a newborn child (adapted size), b: Chimpanzee, c: Neanderthal man

(Chapelle- aux-Saints ), d: adult man.

8

Maturation of the brain and overall growth of the body

Curves of growth for humans and chimpanzees

(the age scale of chimpanzees has ben adapted to the age scale of chimpanzees)

(taken from Lenneberg)

Vertical scales:

Weight of the body /the brain.

Horizontal scales: relative age in years with relevant phases.

9

Evolution of cerebral areas and blood flow while words are seen or heard

Evolutionary comparison of the brains of :

Rats, cats, apes and humans.

Measured energy transport in the visual and the acoustic mode of language.

10

Instrumentality in higher mammals and man

The use of instruments and the goal-oriented adaptation

(manufacturing) of tools can be observed in many orders of animals: ants (insects), birds, and mammals all use simple instruments. In some cases, this allows them to access difficult areas of their body (elephants) or to reach under surfaces. Chimpanzees shape twigs to facilitate “fishing” for termites in termite-hills.

The use of instruments may be inborn and even the evolution of limbs may be connected to instrumental functions, i.e., limbs are “shaped” evolutionarily to adapt for specific instrumental functions. Thus, primate and human hands take over functions originally located in the head (mouth) for attack, defense, preparation of food, for mastication, etc.

Our gestured language, facial expressions, art practices and vocal language presuppose a kind of “instrumental” evolution of the human (and hominid) hand and face.

11

The evolution of tool use

The development of tool-use and tool making implies learning, social imitation or even teaching.

Tembrok (1977: 186 f) distinguishes six levels: ad-hoc tool-using.

purposeful tool-using.

tool-modifying for immediate purpose.

tool-modifying for future eventuality.

ad-hoc-tool-making.

cultural tool-making.

The last stage, “cultural tool-making”, can only be observed in primates and in man.

12

Human tool use in the

Paleolithic

Lithic technologies. Left: reconstruction of the technique; right: products of the Levallois technique.

13

The Design of Lithic

Instruments

The industry had to consider the following factors:

Form and quality of a stone found (this includes a geographic knowledge of places, where they may be found).

Splitting of the stone and isolation of the kernel.

Separation of sharp blades from the kernel.

Use of instruments for choking stone on one side and use of stone instruments for the manufacturing of other instruments (bone and wood).

14

„Chopper“ of the

Olduwai.-culture

East-Africa

15

Abbévillien= 600.000-350.000, second glacial period;

Acheuléen= 350.000-100.000; third glacial period.

Handaxe in the early Paleolithic

(above)

Abbévillien-

Biface (Le Stade)

Le Champs de

Mars

(below)

Middle

Acheuléen

(Saint Acheul)

(cf. Weiner, 1972:

130).

16

(left) Moustérien; until 40.000, fourth glacial period; Charente

(middle), La Quina

(right) , La Quina (all in the Mousterian period).

17

Blades from the

Magdalenean

Blades from the

Solutrean

18

Second lecture

The beginning of graphical art and the first steps in its evolution

2.1

General lines of the evolution of art in the

Paleolithic

• The engravings on tools .

• Paleolithic sculptures .

• Paleolithic cave paintings .

2.2

Moving forms in the classical cave-paintings

(Chauvet, Lascaux and Altamira) .

19

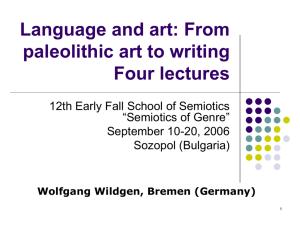

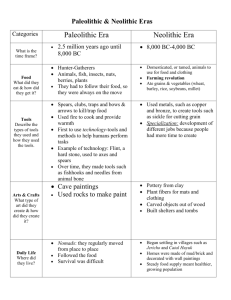

Stages of glaciations

(measured by isotopes of oxygen)

Interglacial

(5e)

Early glacial/temperate

(5d-a)

Early glacial, glacial (4,3)

Full glacial

(2)

Late glacial (1)

Current interglacial ky BP Lithic technologies

(Neanderthals, recent man)

Stylistic periods of cave art in France (recent man)

128-

118

Core/chopping tool

118-75 Flake, core/chopping tool

75-32 Handaxes, scrapers

32-13 Blades

13-10 Microlithic

10-0 elements

Perigordian (ca. 34 ky-

19 ky)

Aurignacian (33 ky- 18 ky)

Solutrean (18 ky –16 ky)

Magdalenian (16 ky –

10 ky)

From tooluse to cave art.

Periods in ky =

1000y.

20

He beginning of graphical art

The beginning of graphical arts can be dated by the first appearance of concentrated color pigments in the context of hominid dwellings. Barham (2001) reports that in south central Africa pieces of iron hematite (often called ochre) and specularite were recovered from an archeological site near Twin Rivers, in Zambia. They had been brought to the site, processed and rubbed against surfaces. One can infer that these materials were used to color objects, bodies or surfaces. The use of such pigments establishes a continuity, which reaches from the archeological sites mentioned (i.e., from 270.000y.

BP) to contemporary hunter-gathers in the Kalahari. The first engravings on stone were also found in Africa and can be dated to 70.000y. BP. One can conclude that archaic Homo sapiens used colors to paint (e.g., their bodies, objects, and/or large surfaces).

21

Rock-engravings and color use

Rock engravings and later plastic art in stone may be understood as the origin of representational art.

As this line also leads to the invention abstract

(motivated by cultural memory) signs and finally to writing, the modern cultures of fine arts and literature have their origin in Paleolithic symbol techniques.

Color was originally used for body-painting, later in the context of funeral practices, and finally in the art of caves (after 40.000 BP).

22

Drawings on portable art

Bone of a mammoth with ornaments from Mezin (Ucrainia)

The engraved bone in the possession of a person and the engraving on it may be used as a prototype (or a model of imitation) which orients further perception of similar objects. It is also an object of value (it can be given, stolen, inherited or buried with the owner).

Becoming an object of value marks the point of transition to ritual and magical objects.

23

From: Sanchidrián, 2001: 12

Varieties of Venus-Figures in

Western- and Eastern

Europe.

A: Willendorf; B: Lespuge;

C: Grimaldi; D: Dolné-Vêstonice,;

E,F und L: Kostienki;

G: Khotylevo; H und J: Avdevo;

I und K: Gargarino.

The dominance of female statuettes and female symbols

(“vulvas”) was interpreted as the consequence of a more

“gendered” society in the Upper

Paleolithic. Eventually a more egalitarian society was replaced by a society with social differentiation and a divergence between female and male roles.

24

Abstract representations of human bodies

Males and females

Russia.

25

Paleolithic cave paintings

Cave paintings occur mainly in an area north and west of the

Pyrenees: mainly in Périgord, Toulouse (France) and

Cantabrica (Spain). Probably the area was a very early economic “Kulturbund” (network of civilizations) in Europe.

The herds of reindeer (as in northern Finland today) defined the relevant ecological dynamics. They probably came to the plains in winter and returned to higher grounds in the

Pyrenees, the Cantabrica Mountains or the Massif Central in

France in summer. The populations of Cro-Magnon men followed the herds and thus met other populations in southern

France and northern Spain.

Other forms of Paleolithic art show an extension of this cultural region to Switzerland, Italy, Southern Germany and

Eastern Europe.

26

Magdalenean caves in France.

27

28

Magdalenean caves in Central and Eastern Europe. Maps from Sacchi, 2003:14f.

The syntax of cave paintings

(narrative or hierarchical)

The field of depicted animals on the ceiling of the cave in

Altamira (Northern Spain).

Main features:

•Natural shape of a herd.

•Filling of a given surface with a quasi-regular structure order.

•Question: is the sequence a narrative one or is the order rather hierarchical?

29

Drawing techniques and body motion

Monochrome drawing of a horse (Peña de Candamo).

30

Patterns of locomotion are not only relevant for the content of pictures but also for their production. Beltran et al (1998:

72) have shown that painters in the cave of Altamira stood with their left arm on the cave wall and traced along it to get a long curved line; i.e., they used their (left) arm and hand as a mold for lines. In a similar way the natural motion of the arm with fixed body was the basis for larger curved lines, e.g., the shoulder and back of a bison, i.e., the human limbs were used as instruments in a ritualized act of painting. The drawing of a bison can thus be decomposed into a series of natural motion patterns, which begin at the head and end at the hind legs (variants of this technique are common).

The surface can be further structured by lines which separate light and dark parts, or by areas with different color or texture and further details can be added. In this context it is worthwhile to note that certain body parts of animals receive special attention: the hair of a bison or its eye and nose (in Altamira), the heads of horses (e.g., a sequence of four heads with necks in cave Chauvet) and of lions (e.g., the sketched or elaborated heads and necks in cave.

31

Polychrome pictures of moving animals in the Cave Chauvet (France)

Battle between two rhinozeros

The oldest cave with high-level painting yet known is the cave Chauvet in the valley of the Ardèche (confluent of the Rhône north of Orange). Different periods of visitation are dated between 31 and 23.000y. and thus belong to the

Aurignacian. Picture taken from: Chauvet (1997: 64 f.).

32

A group of chasing lions; Cave Chauvet. Picture taken from: Chauvet (1997: 64 f.). 33

A bison which turns ist head in attack;

Taken from

Chauvet, 1997

34

Details of horses

Taken from

Chauvet, 1997

35

The cultural achievement of Paleolithic art presupposes a rather general grid of meanings on the level of values in a probably multilingual society of hunters. It would be exceptional if the existence of a large-scale system of values for exchange had not produced a collective system of meanings.

The diversity of conventional signs (cf. Leroi-Gourhan,

1992: 137-140) shows a range of distribution corresponding in size to actual dialect-areas and suggests that the populations living in the Franco-Cantabric area had many different subcultures.

Nevertheless these “dialects” formed an assembly on the level of basic semantics and pragmatics used in cultural contacts, rituals, in the oral tradition of myths and the practice of rituals.

They formed probably one of the largest preliterate symbolic civilizations before the introduction of writing.

36

Third lecture

The evolution of art in the Mesolithic

3.1

From iconic schemata to abstract signs .

3.2

The representation of humans in a social context .

3.3

The disappearance of the Sahara civilizations .

37

Paleolithic paintings contain many signs, which cannot be interpreted as pictures or figures. The transition between iconic signs and abstract signs (symbols) occurs first with very frequent contents. Two human body-parts appear regularly in the paintings and engravings:

The human hand.

The female vulva.

In the case of the hand the most concrete picture is created either by pressing the (left) hand on the wall and painting the contours (or by spraying chewed color with the mouth) or by painting the hand with color and pressing it against the wall. The picture is really the trace of the hand (it indicates the act of touching the wall with the hand). Other tokens abstract the shape of the human hand to a line (a band) with three, four, five branches.

38

First signs of abstraction

Styled Representations of hands

Cave Santian (Spain)).

39

The relation of hands to their body is metonymical (pars pro toto), i.e., one can guess the whole if one has the necessary knowledge, which is easy in the case of the hand. In some cases, the hands are deformed (e.g., have only four fingers); they could therefore be the personal signature of a painter; some authors even guessed an underlying gestured language.

40

Methonymic abstraction

Sketch of a deer’s head

Contours of a deer’s head

Giant deer

41

Many other pictures cannot be linked with specific contents, from which they are derived. Leroi-

Gourhan (1992: chapter IX) made an inventory of the Franco-Cantabric signs and distinguished three major classes:

small signs (e.g., sticks and ramified forms),

full signs; e.g., triangles, squares, rectangles (tectiforms), key shapes (clavi-forms), and punctuated signs.

Leroi-Gourhan comes to the conclusion that all these signs have only a very indirect association with the animals represented in the paintings. They are a supplementary code. This is very clear in Lascaux, where signs and pictures are systematically combined into one gestalt and have corresponding sizes (cf. ibidem: 337).

42

Combination

(and separation) of pictorial and abstract signs in the

Paleolithic period.

(cf. J. Jelinek, 1975,

433).

The abstract sign is of the tectiform type.

43

The small signs could be derived by “disjunction”, i.e., certain figural features from pictures are isolated, cut off. The general tendency is one of geometrical abstraction. Small pictures as in portable art could have triggered the abstraction.

The conventionalized miniature signs were later added to full-scale pictures in the cave paintings.

This is the same process as the one observed in the evolution of early writing systems, e.g., in

Egypt.

Leroi-Gourhan associates these signs with the male sex (as phallic symbols). Full signs are associated with the female sex. Either they are derived from the form of the vulva, or from a female profile (without head and feet).

44

The signs called “tecti-forms” or rectangular (cf. ibidem: 208 f.) look like huts or shelters and could refer secondarily to the domain of females (In a matrilineal society, daughters inherit the house and objects in the house and these are associated with the female sex). Figure 17 shows some examples from Leroi-Gourhan (1992: 319).

The punctuated signs can be related to a basic technique of painting and engraving, i.e., to aligned points, which produce a curve or two rows of them, which fill a surface. It is thus a discrete variant in the representation of lines and surfaces. There is some evidence that counting or representing mathematical structures may underlie these signs.

45

A list of abstract symbols

Tectiform symbols

1-16;

1-10 Dordogne

( Les Eyzies)

11-16: Northern

Spain (Altamira,

Castillo, u.a.)

17 23: isolated signs.

46

The transition to the Mesolithic (after the last ice-age and after the Magdalenean

17.00to 11.000)

In the period between 12.000 and 7.000y. BP, i.e., just before or after the rise of agriculture, a wealth of engravings is found in which humans occupy the central place. The arrow had been invented and chasing (probably also warfare) had been sophisticated. The individual huntsman or the group of hunters and the animal (sometimes the enemy) are the major topics. The scenes are very dynamic as they show people and animals running, attacking, fleeing. In many cases, there is a basic relation, e.g., a huntsman shoots at an attacking ibex, four huntsmen with a leader, or a battle between two groups, etc. We could say a relation or a valence schema is realized in the painting.

47

Art of the Levante (Spain) ca. 9-8 000 BP

48

Transition to the Meso- und

Neolithic

Northern Sahara (Kargur Talh) (Neolithic 4-5. Thou. B.C.)

The Franco-Cantabric had parallels in northern Africa; the style resembles the rock engravings in the Sahara Atlas and the oasis Fezzan (south of Tripoli).

Between 7 and 6.000y. BP cultures based on cattle breeding reached this area from Sudan. They continued the same realistic style (mainly with contours engraved in the rock) but with different contents.

49

The disappearance of the

Sahara civilizations

The transition between Mesolithic and Neolithic civilizations may have its origin in the area north of the Sahara, which was an ideal zone for hunting and later for cattle breeding. A huge amount of rock engraving has been discovered in this area. Probably this civilization which was in contact with first cattle breeding civilizations in the Sudan immigrated to Egypt and the near

East, when the climate became hot and the water supplies were dramatically reduced.

50

Distribution of rock-engravings in

Northern Africa.

Transition between an iconic engraving and an ideogram.

The neolithic cultures of the Sahara had not only cattle breeding, they also demonstrate the domestification of sheep, horse and (later) dromedary.

Taken from: Striedter,1983: 258 (map) and 11 (pictures).

51

Rock-engravings in the Alps as a reminiscence of a cultural stage preceding the modern writing systems

The rock-engraving in Neolithic Europe will continue these traditions and there are even current populations in Australia and south Africa who still practice rock-engraving with a similar function (one may even consider modern graffiti as a contemporary use with the same expressive function).

The European Alps are a zone where these traditions were conserved (e.g. in Trentino and Val

Camonica).

As some pictures resemble popular games, one may even assume an origin of visual plays like chess and others in the graphical tradition of rock-engravings.

52

The distribution of menhirs with pictures in the province Trentino

The Menhir of

Algund

Museum of

Meran

(Ebers/Wollenik

1982: 47).

53

Selection of typical items in Capo di

Ponte (prov.

Brescia)

(Ebers/Wolle nik

1982:98f).

These rock-engravings belong already to the Neolithic period and continued until the Bronze age. An archeological sensation was the discovery of the Ötzi-man in the Alps who lived 6000 y BP.

54

Type of figure found in rockengravings in the Alps

Such geometrical patterns were probably also the starting point for the invention of many rulegoverned games using graphical schemata.

If de Saussure was inspired by chess as a metaphor of language as a rule governed system, he should rather have referred to the Mesolithic /

Neolithic evolution of symbolic games than to the much older system of language.

55

Fourth lecture

The evolution of writing

4.1

Developments after the Neolithic revolution .

4.2

Some aspect of the Egyptian writing system and the transition to alphabets .

56

As the Nilotic cultures melted into the civilization of early

Egypt, there was possibly a continuity (in the Mesolithic period) between Paleolithic art in Northern Africa and early writing systems (e.g., in Egypt and Mesopatamia).

The hieroglyphic characters are pictorial (although schematized) and sequential, i.e., they are at the level of semi-symbolic signs in the hierarchy. As soon as signs for a word with one consonant were used as signs for this consonant, a consonantal alphabet could be created. It remains controversial if Mesolithic sign systems really contributed to the evolution of writing. Coulmas (1989:17) enumerates three characteristics of writing:

1. It consists of artificial graphical marks on a durable surface; 2. its purpose is to communicate something; 3. this purpose is achieved by virtue of the marks’ conventional relation to language.

57

From object-language to writing

Between 8000 BC and 3000 BC very simple „object languages“, where small-scale sculptures represent their objects, existged.

Later two-dimensional contours represented the objectsigns included in a jar.

They finally lead to the first systems which may truly be called writing systems. These presuppose the political and economic organization of the first empires and cities.

Cf. Schmandt-Besserat (1978: 82).

58

Transition to writing (the last

10.000 years): Object signs

Original functions:

•Representation of objects for the purpose of bookkeeping (a sign stands for an object in the economic world).

•Creation of a representational universe of discourse (where the buying, selling, transfer., loss etc. of objects is represented).

•Calculation (origin of mathematics).

59

The abstraction process from pictures to writing symbols corresponds to a general mnemonic principle. This is also valid for messages in an object language employed by

Yoruba tribes and in Australian messenger-sticks. The message is coded for the messenger, who “reads” it when he arrives after a long journey. This guarantees that he does not forget important contents, but it presupposes that he knows the message. This means that the written message can only be “read” accurately if the reader has a knowledge of its contents independently from the “written” document (cf. Friedrich, 1960: 17).

Full-fledged writing-systems presuppose a writing industry, i.e., the frequent production and usage of writing in proper contexts. The Paleolithic stone industries established the context for the manufacturing of functionally optimal artifacts (weapons, tools), the Mesolithic and Neolithic picture and symbol industries established the necessary context for writing systems.

60

The communicative/functional usage of writing was systematically developed in Mesopotamia, which became a melting pot of many cultures and concentrated large populations into one organized political system. The paths for the exchange of goods, values, and ideas became complex and difficult to control. The civilizations of Mesopotamia (and the “golden crescent”) took their new shape between 11 and 8.000y. BP. The first “token” systems, called “object languages” by Schmandt-

Besserat (1978), appeared ca. during this area and were not dramatically changed for almost five millennia. Only in the

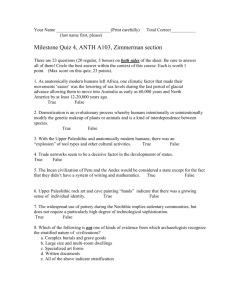

Bronze Age, between 7,500y. BP and 5,100y. BP, did the number of tokens increase and their shape differentiate and finally give rise to Sumerian writing (ca. 5.000y. BP; cf. also

Friedrich, 1966: 42 f.). The context was not religious but economic. The storage, transport and control of goods motivated a system of bookkeeping. A closed jar contained a number of symbolic objects, which stood for the goods sent to a destination.

On the jar, a list of the symbolic objects in the jar was marked.

The next slide shows the state of the system in the intermediate period of the Bronze age (before Sumerian writing arrived).

61

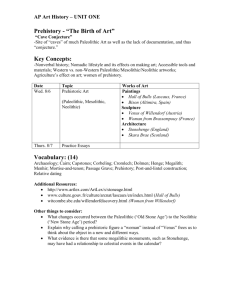

Early objectsymbols

(choice from a field of 12 categories).

62

If we look closer at the symbolic objects in the table given by Schmandt-Besserat (1978: 87 f.) we notice the geometrical and abstract character of the signs: spheres, discs, pyramids, cones, tetrahedrons, biconoids, and ovoid are the basic shapes. On these bases, other abstract geometrical shapes are marked (in a lower dimension): holes, lines in/on the sphere, disk, etc. The

Sumerian pictograms later flatten the symbolic objects to two-dimensional shapes.

The direction of writing was first rather accidental, later an organization into vertical columns came up with the order of columns from left to right and inside the columns from top to bottom. Finally the whole arrangement was rotated by 90 o ; the first column on the left became the first line on the top. In the same move the symbols were rotated by 90 o .

63

Writing industries in

Egypt

The scribe and his instruments. A wood cut 4700 years old

The scribe of the pharao, Hesire, has:

On his shoulder a plate

„ ink-cake“,

1. A container in wood for the brush,

2. A container with water to make the brush wet.

(taken from: Claiborne,

1976: 93).

64

Hieroglyph of life from the grave of Tutanchamun (3450 years old)

INSCRIPTION IN THE MIDDLE:

Neb = hieroglyph for basket

Kheper (hieroglyph for the

Skarabäus)

Re = hieroglyph for the Sun

Together they compose the proper name of the possessor:

Nebkheperure

The three strokes below the

Skarabäus stand for the vowel

„u“

(taken from: Claiborne, 1975:

107).

65

Hieroglyphs in Egypt

Signs for nouns

/concrete contents.

Signs for verbs

/processes.

66

As a word stood for a whole family of words with the same root, determina-tives were used to distinguish different word-forms. As only consonantal patterns were mapped into written symbols, the written forms were still ambiguous. There were two major methods of disambiguation:

By a kind of “punctuation” the vowels could be marked.

The method of punctuation was adopted by many civilizations and languages in the Near East (still observable today in Arabic and Hebrew).

Special symbols for vowels were inserted into the sequence of consonantal symbols. This method was first adopted by the Phoenician and later by the Greek,

Latin and Cyrillic alphabets. For this purpose signs of consonants not used could be reinterpreted.

67

Further developments in Egypt

Hieroglyphs:

First simplifications in the 3rd millennium B.C.

Hieratic :

Latest text 3rd century AD

Demotic:

Latest text: 476

AD.

Friedrich, 1966:195

68

Diffusion of the writing-systems between 1600 BC. (yellow) and alphabets 450 BC. (green)

69

The evolution of the Greek alphabet from the Phoenician

Friedrich, 1966:

275

Partial list.

70

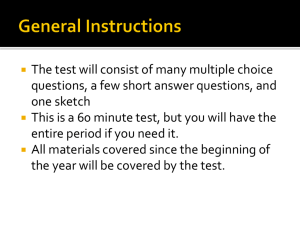

A rough summary of the evolution of writing

Paleolithic period

36.-12.000 BP

Abstract symbols besides realistic pictures

Realistic pictures dominate

Mesolithic period

12.000 - ….. BP

(the end depends on the region)

Rock engravings and paintings in the

Levante and

Atlas

Abstract signs increase and form a huge lexicon

Neolithic period

10.000-5.000 BP

(before the rise of the classical

“high” cultures)

Beginning of writing industries

Cultures in

Mesopotamia and Egypt 5.000-

1500 BP (latest text 476 AD)

Rock engravings, object languages

Cuneiform writing hieroglyphs

Complex systems of writing evolve; which imply also a phonological analysis

Phoenician –

Greek, Roman … cultures 2.500 to modernity

Alphabet writing systems

Dominance of systems based on the phonological motivation of writing

71

Ideographic systems

Different solutions for the design of writing systems were in conflict and in Europe and western Asia the ideographic systems disappeared and the alphabetic principle expanded into all directions.

Only in China did the ideographic writing system survive. It had found its very abstract shape already in the old bone-engravings (1 400-1 200 B.C.). The basic economy of these systems has, in spite of its ideographic character, structural similarities with the alphabetic systems.

In Japan and Korea mixed systems were created. In

Japan phonetic syllables are designed by writing symbols and completed by Chinese ideograms.

72

The ideogram can be decomposed into more elementary strokes (ca. 20). Thus the number of elementary signs corresponds roughly to the number of signs in an alphabet (22 to 30).

At the next level of complexity one can distinguish

24 different radicals. Thus the sign for sun (see above) consists of four strokes.

The complete signs are fitted to an imaginary square. Similar tendencies can be observed in

Hebraic quadratic letters, Roman capital letters and the “Antiqua” introduced in the Renaissance.

73

Chinese signs for words and their original pictorial form

Child

Tree

Door

Arrow

Heart

Word

Rain

Dog

Snail

Hand

Richness

Field.

74

Conclusions

There is a line which leads continuously from artifact-industries already presupposing the semantics and pragmatics of a natural language to art, writing and mathematics.

The basic principles which organize these levels of semiotic evolution should be formulated in a common language.

Such a scientific language must have geometrical and combinatorial powers.

75

Bibliography (selected)

Barham, Lawrence S. (2002). Systematic Pigment Use in the

Middle Pleistocene of South-Central Africa. Current

Anthropology, 43 (1), 181-190.

Bax, Marcel, Barend van Heusden and Wolfgang Wildgen

(eds.), 2004. Semiotic Evolution and the Dynamics of Culture.

Lang, Bern .

Chauvet, Jean-Marie, Eliette Brunel Deschamps, Christian

Hillaire (1995). La grotte Chauvet à Vallon-Pont-d’Arc. Paris:

Seuil.

Coulmas, Florian (1992). The Writing Systems of the World.

Oxford : Blackwell Daniel, Hal (1989). The Vestibular System and Language Acquisition. In Wind et alii (1989: 257-271).

Földes-Papp, Karoly (1984). Vom Felsbild zum Alphabet. Die

Geschichte der Schrift von ihren frühesten Vorstufen bis zur modernen lateinischen Schreibschrift. Stuttgart: Belser.

Foley, William (1997). Anthropological Linguistics. An

Introduction. London: Blackwell.

76

Friedrich, Johannes (1966). Geschichte der Schrift. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung ihrer geistigen Entwicklung.

Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

Gamble, Clive (1986). The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe.

Cambridge: Cambridge U.P. Gamble, Clive (1999). The Palaeolithic

Societies of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P..

Gibson, Kathleen R. & Tim Ingold (Eds.) (1993). Tools, Language and Cognition in Human Evolution.

Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

Jelinek, Jan (1975). Das große Bilderlexikon des Menschen in der

Vorzeit. Bertelsmann: Munich.

Lenneberg, Eric H. (1967). Biological Foundations of Language

(with appendices by Noam Chomsky & Otto Marx). New York: Wiley

LeroiGourhan, André (1992). L’art pariétal. Langage de la préhistoire. Grenoble: Jerôme Million.

Martin, Alex (1998). Organization of Semantic Knowledge and the

Origin of Words in the Brain. In Jablonski & Aiello (1998: 69-87).

Rhotert, Hans (1956). Die Kunst der Altsteinzeit. In Weigert (1956:

9-52.

77

Sacchi, Dominque (2003) Le Magdalénien. Apogée de l’art quaternaire. La maison des roches, Paris.

Sanchidrian, José Luis (2001). Manual de arte preistorico. Barcelona: Ariel.

Schmandt-Besserat, Denise (1978). The Earliest

Precursor of Writing. Scientific American, June 1978

(reprinted in Wang, 1982 (chap. 10): 81-89).

Striedter, Karl Heinz (1983) Felsbilder Nordafrikas and der Sahara. Steiner: Wiesbaden.

Tembrok, Günter (1977). Grundlagen des Tierverhaltens.

Braunschweig: Vieweg.

Weigert, Hans (Ed.) (1956). Kleine Kunstgeschichte der

Vorzeit und der Naturvölker. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Weiner, J. S. (1972). Entstehungsgeschichte des

Menschen. Lausanne: Editions Rencontre.

78

Wenke, Robert J. (1999). Patterns in Prehistory. Humankind’s first

Three Million Years. Oxford: Oxford U.P.

Wildgen, Wolfgang (2001). The Paleolithic Origins of Art, its

Dynamic and Topological Aspects, and the Transition to Writing, in

M. Bax, B. van Heusden & W. Wildgen (Eds.), Semiotic Evolution and the Dynamics of Culture., Bern: Lang.

Wildgen, Wolfgang, 2004. The Evolution of Human Languages.

Scenarios, Principles, and Cultural Dynamics. Series: Advances in

Consciousness Research, Benjamins, Amsterdam.

Wildgen, Wolfgang, 2005. Le problème du continu/discontinu dans la sémiotique de René Thom et l’évolution des langues. in: Cahiers de Praxématique 42 :121.143.

Wildgen, Wolfgang, 2006. The Semiotic Hypercycle and the Run-

Away Process of Linguistic (Symbolic) Evolution. Contribution to the:

Cradle of Language Conference, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 7 – 10

Nov 2006.

79

Τέλος Ενότητας

Χρηματοδότηση

Το παρόν εκπαιδευτικό υλικό έχει αναπτυχθεί στα πλαίσια του

εκπαιδευτικού έργου του διδάσκοντα.

Το έργο «Ανοικτά Ακαδημαϊκά Μαθήματα στο Πανεπιστήμιο

Ιωαννίνων» έχει χρηματοδοτήσει μόνο τη αναδιαμόρφωση του

εκπαιδευτικού υλικού.

Το έργο υλοποιείται στο πλαίσιο του Επιχειρησιακού Προγράμματος

«Εκπαίδευση και Δια Βίου Μάθηση» και συγχρηματοδοτείται από την

Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση (Ευρωπαϊκό Κοινωνικό Ταμείο) και από εθνικούς

πόρους.

Σημειώματα

Σημείωμα Ιστορικού Εκδόσεων

Έργου

Το παρόν έργο αποτελεί την έκδοση 1.0.

Έχουν προηγηθεί οι κάτωθι εκδόσεις:

Έκδοση 1.0 διαθέσιμη εδώ.

http://ecourse.uoi.gr/course/view.php?id=1201 .

Σημείωμα Αναφοράς

Copyright Πανεπιστήμιο Ιωαννίνων, Διδάσκων:

Καθηγητής Χρήστος Α. Δερμεντζόπουλος. «Εισαγωγή

στην Ανθρωπολογία της Τέχνης. Τέχνη και Κουλτούρα,

Language and art ». Έκδοση: 1.0. Ιωάννινα 2014.

Διαθέσιμο από τη δικτυακή διεύθυνση: http://ecourse.uoi.gr/course/view.php?id=1201 .

Σημείωμα Αδειοδότησης

Το παρόν υλικό διατίθεται με τους όρους της άδειας

χρήσης Creative Commons Αναφορά Δημιουργού -

Παρόμοια Διανομή, Διεθνής Έκδοση 4.0 [1] ή

μεταγενέστερη.

• [1] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ .