Paper 1: title - St. Olaf Pages

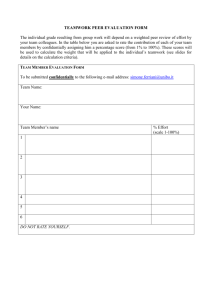

Peer Evaluation and Feedback in Teams

Angela Boone, Monzong Cha, Sarah Cole, Arwa Osman

St. Olaf College

Sociology & Anthropology

Fall Semester 2012

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Professor Ryan Sheppard for her keen support and guidance throughout our research and Teaching Assistant Charlotte Bolch for all her help. We would also like to thank the Director of Institutional

Research, Susan Canon, for her help with our sampling. Finally, we would like to thank the Sociology/Anthropology

Department for their funding throughout our research.

1

Abstract

Recent literature suggests that students who prefer informal feedback to formal feedback believe it is easier to do and more direct than formal feedback. Studies have shown that the quality of a team’s product and learning improves with the use of peer evaluation. Peer evaluation enhances a student’s understanding about other peers’ ideas, and helps develop social and transferable skills. To investigate this dynamic further, we analyzed students’ experience with peer evaluation, attitude towards peer evaluation and feedback in classroom teams.

Literature Review

As more schools and workplaces utilize teamwork, there has been increasing interest in facilitating a successful and effective teamwork environment, and thus is a subject of much research. A team is defined as having the following characteristics: sharing a common goal, depending on other members, agreeing on a common approach, having members with complementary skills and knowledge, and consisting of less than twenty members (Foster and

Wellington 2009). Researchers investigating teamwork in colleges and the workplace have focused on a number of topic areas including cohesion (Aritzeta, Ayestaran and Swailes 2005), communication (Buljac-Samardzic et al.

2011), leadership (Chen 2010 ) , conflict and conflict resolution (Long, Zhong-Ming, and Weui 2011) , and peer evaluation (Arnold et al. 2005; Bowes-

Sperry et al. 2005; Dommeyer 2006; Lizzio and Wilson 2008; Marls and Panzer 2004; Ohland et al. 2005; Wen and Tsai 2006).

Studies of peer evaluation and feedback have examined the numerous types (Arnold et al. 2005; Dommeyer 2006; Tseng and Tsai 2010; Ohland et al. 2005; Wen and Tsai 2006), different incentives (Towry 2003), attitudes towards peer evaluations (Arnold et al. 2005;

Bowes-Sperry et al. 2005; Lizzio and Wilson 2008; Tseng and Tsai 2010; Wen and Tsai 2006), the effectiveness of the evaluation (Marls and Panzer 2004; Ohland et al. 2005; Wen and Tsai

2006) and skills gained from doing peer evaluation and feedback ( McKinney and Denton 2005).

2

Terminology

The literature defines the following key terms: Peer assessment, also referred to as peer evaluation, is defined as the process whereby groups of individuals rate their peers, which may involve activities such as informally commenting on peers work or filling out an evaluation form

(Wen and Tsai 2006). Feedback is defined as giving information to a student about his or her performance on a certain task (Lizzio and Wilson 2008). These definitions give a foundation of understanding the rest of the literature review on teamwork.

Types of Peer Evaluation

The design and administration of peer evaluations are important in developing overall successful teamwork. Studies of different types and forms of peer evaluation have addressed the different ways of conducting evaluation, in order to find the most effective methods of disseminating peer evaluations. Peer evaluations can be conducted inside or outside the classroom (Dommeyer 2006), on paper or online (Wen and Tsai 2006), in a formative or summative manner (Ohland et al. 2005), and formally or informally (Arnold et al. 2005).

Studies show that when students complete evaluations outside of the classroom, they are more critical of their peers and give lengthier responses (Dommeyer 2006). Wen and Tsai

(2006) found that online forms of peer assessment allow for a more private and comfortable environment for evaluating peers. It also saves time, money, and speeds up the grading process. Thus, online peer evaluation provides higher quality feedback because of the comfortable environment, privacy, and anonymity (Wen and Tsai 2006).

Ohland (2005) and his research team studied two types of peer evaluations: formative and summative. Formative peer evaluation is feedback given to students with the objective of improving their teamwork skills or product in the future. Formative peer evaluations tend to be longer and more detailed in order to thoroughly highlight effective and ineffective behaviors.

This informs students on areas where they excel and identify opportunities for improvement.

Students evaluate their peers more critically when the evaluation is not tied to a reward system

3

(meaning formative evaluations are not counted towards one’s grade for the course) (Ohland et al. 2005).

Summative peer evaluations describe a person's past performance on a team. This evaluation is primarily used as an indicator of individual accountability in order for instructors to adjust grades to reflect individual work. Researchers note that when summative assessments are tied to incentives, such as receiving better grades, this can be a powerful motivating force for students to earn better grades. Benefits to summative evaluations include making individual contribution and accountability more identifiable, as well as disseminating performance criteria that all students are aware of (Ohland et al. 2005).

A study on medical students in the Midwest found that students have different preferences for evaluations. Some students prefer informal feedback whereas others prefer formal feedback. The students that prefer informal evaluation believe it is easier to do and is more direct. Informal feedback is also shown to be more widely utilized and practical in teamwork experiences, as team members can seek it at any time during teamwork, rather than using formal feedback which usually occurs once or twice during a given period of teamwork

(Arnold et al. 2005). According to Larson’s (1989) research findings, when informal feedback is especially sought out, it can have a positive influence on improving a team member’s work, foster greater self-confidence, and team cohesion. This is achieved through informal and more naturally-occurring daily interactions between team members (Larson Jr. 1989).

Incentives of Peer Evaluation

Research on graduate business students looked at incentives for doing peer evaluation, the goal behind doing an evaluation, who receives the feedback and how both of these ideas interact with team identity. Incentives for peer evaluation refer to the purpose of doing a peer evaluation. The purpose could be getting a grade when giving them to an instructor, receiving constructive criticism and guidance to improve one’s quality of work, or improving the team dynamic and product. These studies look at the difference between what they refer to as

4

“vertical” and “horizontal” feedback. Vertical feedback is an evaluation that goes to management or a professor, whereas a horizontal evaluation goes to peers or coworkers only (Towry 2003).

The effectiveness of an incentive system is largely determined by team identity, meaning how strongly members develop a psychological attachment to their team. Strong team identity, a result of team bonding, increases a team's coordination on evaluating, thus making vertical systems less effective. For example, strong team unity could result in all members coordinating to give everyone positive feedback, despite completing poorer work. Horizontal incentive systems, which are based on the whole team and not individual outcomes, lead to higher levels of team identity and production as they push each other to do well (Towry 2003).

Incentives are found in summative peer evaluations as well. These incentives result in greater motivation for team members to behave in positive ways because it will earn them higher ratings. Additionally, researchers add that the process of completing summative assessments helps students understand the performance criteria and how everyone will be evaluated (Ohland et al. 2005).

Attitudes Towards Peer Evaluation

The characteristics of a peer assessment system impact students’ willingness to participate in peer assessment. Studies of attitudes towards peer evaluations focus on participants’ perceptions and behavior towards peer evaluation. Through their research on medical students, Arnold et al. (2005) found that the factors which motivate or discourage a student from participating in peer evaluation are the following: students worry that something bad will come out of the assessment (i.e. hurting a peer or their relationship with a peer), the type of evaluation (i.e. formal or informal), anonymous or transparent evaluations, and the environment it is given in. For example, many students reported feeling uncomfortable evaluating peers when it is not anonymous. Students struggle with peer assessment when their peer’s reputation, feelings, and well being were being threatened by their evaluation. Students

5

felt more comfortable assessing a younger student, and are very careful of damaging peer relationships (Arnold et al. 2005).

A study on online peer evaluations found similar resul ts regarding students’ attitudes.

This study, done at two large national universities in northern Taiwan, found that students generally have a positive experience with online peer assessment. Students’ attitudes toward online peer assessment are more positive because they can remain anonymous. Students can freely express their thoughts and ideas about other students’ work with less restriction of location and time (Wen and Tsai 2006).

The impact that peer evaluations have on students’ perception of learning is an important aspect to consider. A study on business students from universities in the U.S. and

Hong Kong explained that students working in teams realized the implications that evaluations have on their learning (Bowes-Sperry et al. 2005). Furthermore, many students believe peer assessment should be part of their grade percentage (Wen and Tsai 2006). Another study found a positive relationship between the portion of the course grade that a peer evaluation determined and the amount of learning reported by students (Bowes-Sperry et al. 2005).

A study involving students from science and engineering, psychology, criminology, law, and art programs, showed that students tend to prefer receiving feedback when it allows for development and improvement over time. A developmental focus is important to keep in mind to help identify goals and strategies for improving and learning on. Additionally, students value receiving feedback that shows engagement or interest from the assessor. The apparent engagement gave students a sense of value and made them perceive fairness in their grade

(Lizzio and Wilson 2008).

Effectiveness of Peer Evaluation

Studies of college students on the effectiveness of peer evaluation takes all of these prior topics into account to determine how useful and helpful peer evaluation can be.

Effectiveness is based on both the process and product of a team’s work. Peer assessment has

6

been found to increase students’ interactions with each other and their instructors (Wen and

Tsai 2006). A study with undergraduate psychology students of a Southeastern University showed that the process of monitoring a team improves coordination of the team because, through monitoring each other, the team is able to determine their pace and adjust accordingly

(Marls and Panzer 2004). An increase in team coordinating may result in an increase of feedback within the team as well. Therefore, if teammates monitor each other there will be more coordination and feedback, which is critical to managing a team (Marls and Panzer 2004). The quality of the product, and thus learning, is improved as a result of peer assessment enhancing a student’s understanding about peers’ ideas, and develops social and transferable skills (Wen and Tsai 2006).

Validity and Reliability of Peer Evaluations

The reliability of peer evaluations is crucial in assigning students accurate grades for their individual contributions in a teamwork setting, as well as maximizing feedback benefits for students. Some biases present in peer evaluation are friendships between team members, popularity of a member, jealousy of certain individuals, and revenge against a team member

(Ohland et al. 2005).

There are ways to increase the reliability of peer evaluations.

For example, in a study of undergraduate engineering students involved in project teams, descriptive instructions on ratings (i.e. “excellent” or “poor”) were found to increase the reliability of the peer evaluation instrument, compared to evaluations where it only stated the rating but gave no descriptions of what the rating meant. This was found to be more reliable because it gave the evaluator clear description of actions and behaviors of these ratings when evaluating peers (Ohland et. al 2005).

Although longer evaluations are more reliable, there is a trade off. Studies have found that students are more likely to fill out shorter peer evaluations more conscientiously than longer ones, and in general longer summative evaluations may be impractical to conduct in classroom settings.

However, including more statements, instructions and definitions of different aspects of

7

teamwork on peer evaluation forms help students recall the different aspects of teamwork and what they are judging in a student, thus contributing to more accurate and reliable evaluations

(Ohland et al. 2005).

Peer evaluation is an important tool in identifying positive skills, and improving the skills that are essential for a well-functioning and effective team, as well as to produce superior quality work. Various team training methods, such as giving instructions on how to deal with team conflict, and utilizing formal and informal peer evaluation and feedback, can be used to improve the process of team performance. Skills that research has identified as being characteristics that workplaces want from college students include: communication, interpersonal skills, motivation, honesty, flexibility, organizational skills, and a strong work ethic. Instruction from professors on how to develop and support these different skills is important in the success of a team. For example, clarifying and receiving concrete and explicit definitions about different team skills, as well as receiving regular formative feedback on team members' performance in this those skills, results in students becoming aware of positive skills they can develop and deliberately apply in their teamwork (McKinney and Denton 2005).

Directions for Future Research & Hypotheses

We plan to explore the gap in the research regarding informal feedback. Our survey questions will investigate students’ experience with informal feedback in college classroom teams. We will look into their experience and attitude towards informal feedback and their comfort giving and receiving it. Testing the effectiveness of informal feedback improving teamwork and the team’s product to determine if that is a helpful tool that should be encouraged in the classroom.

We also plan to explore students’ preferences with types and modes of peer evaluation.

We will investigate their preferences between quantitative (i.e. where students rank their peers) and qualitative (i.e. where students leave comments and suggestions for peers) peer evaluation forms to test if the majority of students prefer an integrated option. We will also explore whether

8

students prefer to complete the evaluation online or on paper, and inside or outside of the classroom. Finding out what mode and type of peer evaluation students feel most comfortable using to evaluate their peers will give insight into the best way to make peer evaluation effective.

While other researchers focused on large universities, medical schools, business schools, and professional schools, we will be looking specifically at students from a small liberal arts college. Our research examines the relationship between experience with peer evaluation and teamwork skills, comfort with informal feedback, as well as attitudes and experience with informal feedback.

Methods

In our study, we conducted research using an online survey in November 2012 to ask students at a small, liberal arts college in the Midwest about their experiences with peer evaluation and feedback in the college classroom. The survey was distributed randomly to students through email. This method is cost-effective, efficient, and appropriate for our limited time frame for conducting our research. We investigated the following hypotheses: 1) Students that have experience with peer evaluation have better teamwork skills than students that lack experience with peer evaluation, 2) The more experience students have in teams, the greater their comfort with informal feedback, 3) Students that have experience with peer evaluation have a more positive attitude and experience with informal feedback than students who lack experience with peer evaluation. We also explored students’ attitudes and preferences towards peer evaluation and informal feedback.

Variables

In one of our exploratory sections we inquired about stud ents’ attitudes and preferences regarding peer evaluation. We looked into students’ general attitudes towards peer evaluation, and their opinion on the grade given for peer evaluation. To do so, we used another index, asking questions such as “Team peer evaluation should be used regularly in classes with team projects”. These questions addressed opinion, hence we used ordinal levels of measurements.

9

The Likertscale of “Strongly Agree,” “Somewhat Agree,” “Neutral,” “Somewhat Disagree,”

“Strongly Disagree,” and “Not applicable” was used. We then used a multiple choice question format to ask about their preferences towards different types and modes of peer evaluation forms. We presented a question about their preferences to type (i.e. location for conducting the evaluation) and another about form (i.e. quantitative, qualitative, or a combination). They then had three choices for each type and form question to choose from. These measurements were nominal because they were different categories (Neuman 2012).

Our second exploratory section focused on students’ experiences and preferences with informal feedback. To measure these concepts we used an index to ask questions about students’ attitudes on doing informal feedback and whether or not they find it helpful. These questions were favorable and attitudinal. This index again used a Likert-scale measurement with the responses “Strongly Agree,” “Somewhat Agree,” “Neutral,” “Somewhat Disagree,”

“Strongly Disagree,” and “Not applicable”. Because students’ attitudes and perceptions were explored on this subject, we used ordinal measurements in determining opinions.

For our three hypotheses, we examined the effects that peer evaluation and team experience have on teamwork skills and attitude towards and experience with informal feedback.

In our survey, we first defined peer evaluation as the process whereby members of teams provide feedback to their team members by filling out an evaluation form. We also defined informal feedback as any feedback that is given in an informal manner among team members in day-to-day interactions. This can range from nonverbal cues (such as an approving smile or a disapproving roll of the eyes) to complimenting or criticizing teammates on their behaviors and work. As we examined students’ experiences with feedback and peer evaluation, these concepts made up our variables. We included sections on both informal feedback and peer evaluation in our survey as students with experience in peer evaluation may be a very selective group, and we wanted to make sure that we would get enough response on our topic. Our independent variables were peer evaluation experience, and team experience, while our

10

dependent variables were teamwork skills, and attitude and experience towards informal feedback.

In our first hypothesis, that students who have experience with peer evaluation have better teamwork skills than students that lack experience with peer evaluation, the independent variable is experience with peer evaluation and our dependent variable is better teamwork skills .

To measure this variable we asked students to respond to a series of Likert-scale statements.

Some examples of the statements students responded to are the following : “I am good at coordinating my e fforts with teammates”, “I express my thoughts to teammates clearly and respectfully”, and “I am good at sticking to a team’s time limit and deadlines”. We used the following response categories for each statement: “Strongly Agree,” “Agree,” Somewhat Agree,”

“Somewhat Disagree,” “Disagree,” and “Strongly Disagree." These response categories make the dependent variables ordinal since they are opinion measures (Neuman 2012).

For our second hypothesis, that the more experience in teams the greater the comfort with informal feedback , the independent variable was experience in teams and our dependent variable was comfort with informal feedback. To measure this variable we asked students to respond to a few favorable, attitudinal Likert-scale statements regarding their comfort giving and their comfort receiving informal feedback. We used the following response categories for each variable: “Strongly Agree,” “Agree,” “Somewhat Agree,” “Neutral,” “Somewhat Disagree,”

“Disagree,” “Strongly Disagree,” and “Not applicable”. Comfort with informal feedback is an ordinal measure because this dependent variable measured opinions; hence the response category has distinct categories for respondents to choose from and can be ordered (Neuman

2012).

For our third hypothesis, that students that have experience with peer evaluation have a more positive attitude and experience with informal feedback than students who lack experience with peer evaluation , our independent variable was experience with peer evaluation, and our dependent variables were attitude towards and experience with informal feedback. To measure

11

these variables, we asked participants to respond to a few favorable, attitudinal and behavioral

Likert-scale statements. An example of a statement we asked students about their attitude regarding informal feedback is: “I am comfortable giving informal feedback in teams.” The questions asking about students’ experiences in their most recent team, asked specifically if their teammates' informal feedback improved the team's final product or their own performance.

We used the following response categories for each statement: “Strongly Agree,” “Agree,”

“Somewhat Agree,” “Neutral,” “Somewhat Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Strongly Disagree,” and “Not applicable”. These response categories make the dependent variables ordinal, as they are opinion measures (Neuman 2012).

Sampling and Sampling Procedure

We first held a focus group of 9 students who were individuals recruited from a private liberal arts college to discuss their past experiences with peer evaluation and feedback. This allowed us to get a general idea of students experience levels and opinions, and allowed us to refine our questions and to target specific attitudes or behaviors when creating our survey. Students from this same private liberal arts college in the Midwest made up our target population for our survey.

With a sampling frame of roughly 3,000 students, we applied the rule of thumb method to determine what sample size we should use for this group. For populations that are less than

1,000, the rule of thumb states that the sampling size should be 30 percent. As our population was around 3,000, we estimated that our target population should be around 25 percent of our overall population (Neuman 2012). Respondents were selected through a simple random sampling procedure to ensure members of the population had an equal chance of being selected (Patten 2001). As part of creating our sampling frame, we excluded those who participated in our focus group discussion and students currently enrolled in our research methods class because both groups were part of the research process. We also excluded

12

atypical students such as part time college students and students who are studying abroad.

Those who were 18 and younger were excluded for ethical reasons.

We sent our survey out to the random sample of students who remained after excluding parti cipants. Our attempted sample size was 707 students, who received the survey via email.

We had 251 out of 707 respondents for our survey, resulting in a response rate of 35.5%. Our sample was 66.5% female (167/251) and 28.7% male (72/251). Our sample was 30.3% freshmen (76/251), 27.1% sophomores (68/251), 24.3% juniors (61/251), and 14.7% seniors

(37/251).

Validity

To ensure the validity of our measures, we used two main types of measurement validity: face validity and content validity. To attain face validity (that the method of measurement fits with our terms’ definition) we analyzed our survey questions and reviewed them with an experienced researcher (Neuman 2012). We had also consulted our work with our classmates who were in the process of conducting similar research. We also achieved face validity by making sure the construction of our survey was authentic and gave a fair representation of social life from a viewpoint of someone who lives it (Neuman 2012).

To attain content validity, that the measure captures the full meaning, and affirms that all aspects of our conceptual definitions were well measured, we reviewed our survey questions to utilize our conceptual definitions (Neuman 2012) . The discussions from our focus groups enabled us to specify our conceptual definitions, as we needed to define terms. We further specified the definitions after receiving feedback from the members about what they believe is included in peer evaluations and feedback. To further achieve content validity, we created survey questions that addressed many aspects of measurements. For example, with peer evaluation we included aspects of where and how it’s used and if it helps. This feedback enabled us to construct accurate measures that included the entire meaning of our terms. It also provided us with feedback on which questions needed improvement so we could clarify them.

13

Reliability

Reliability, meaning dependable and consistent research methods, is necessary for any valid research. We strived to ensure reliability in our survey through several tactics. For instance, using focus groups we were able to clearly conceptualize our terms, and then revised these definitions based on the information found in our scholarly journal articles. We used precise levels of measurements such as indexes and scales. We used multiple indicators for peer evaluation and feedback through a variety of questions. To pilot test our survey we had other classmates take our survey and critique it for improvements. We changed wording to make questions easier to understand and worked to avoid halo effect, which is a string of consecutive positive answers. (Neuman 2012)

Ethics

We followed the requirements of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the college to ensure that our research aligned with their ethical standards. We applied for Type 1 IRB approval, as the main purpose of our research was to advance the knowledge of our research team and the college (IRB 2010). Throughout conducting our research our main ethical concerns were voluntary and informed consent, having no repercussions for not answering, anonymity, protection of privacy, age, and avoiding the potential for emotional stress. To gain voluntary and informed consent we sent a cover letter to students to inform them of the purpose of our study. We reassured them that their responses would be completely anonymous, as we did not collect names or any distinctive identifying information. Although we did know the names of the students who entered their names into a drawing and won our incentive prize but we had no way of connecting them to their response.

In the cover letter, we informed students that participating in the study was completely voluntary, that they can skip questions, and can drop out of the study at any time. We also informed participants that they would be giving implied consent by filling out our survey. We assured students that there would be no repercussions if they chose not to take the survey or

14

answer certain questions. To ensure anonymity we never received a list of the participants’ names and did not collect enough identifying information to determine their identity. To protect privacy of our respondents we reported only generalizations and statistics on the students as a whole, not singling specific cases. Excluding students eighteen and under allowed us to avoid the risk of legal harm to minors. To protect students from any possible emotional harm we made sure to notify them that they could drop out of the survey at any time.

Results

To test our hypotheses on the effects that experience with peer evaluation and informal feedback in teams have on students’ teamwork, success, and attitude we did a series of statistical tests to find if significant relationships existed in our hypotheses. We hypothesized that students who have experience with peer evaluation have better teamwork skills than students that lack experience with peer evaluation, and also that the more experience students have in teams, the greater the comfort with informal feedback, and lastly that students that have experience with peer evaluation have a more positive attitude and experience with informal feedback compared to students without peer evaluation experience. We also investigated descriptive univariate data regarding college students’ responses to our survey questions about their preferences regarding peer evaluation and informal feedback.

Univariate Data

Our univariate analysis explored college students’ preference of peer evaluation use in the classroom setting, frequency, and whether it should count towards their grade. We also examined college students’ preference of the form and type of peer evaluation.

When asked which form of peer evaluation students preferred, 66.4% preferred a form that asks for numerical ratings and comments and suggestions about their teammates, 23.2% prefer a form that only asks for them to give comments and suggestions about their teammates, and

10.4% preferred a form that only asks them to give a numerical rating of their teammates. (See

Figure 1)

15

Figure 1: Students’ Preference of Peer Evaluation Form

We also found that 49.2% preferred an online form that team members complete outside of the classroom, 27.4% preferred a paper form that team members complete outside of the classroom, and 23.4% preferred a paper form that team members complete during class. (See

Figure 2)

Figure 2: Students’ Preference of Peer Evaluation Type

16

Our findings also revealed that students agreed that peer evaluations should be used regularly in class (78.9%), count towards their grade (60.9%), and that when peer evaluation counts toward their grade it motivates them to work harder in their team (71.6%). The majority of our respondents also reported that peer evaluation improved their group's teamwork (50%), and that it improved their team’s final work (52.4%). (See Table 1)

Table 1: Exploratory Variables on Peer Evaluation

PE should be used regularly in class

PE should count toward grade

When PE counts toward my grade, it motivates me to work harder in my team

PE improved my group's teamwork

PE improved my team's final work

Agree (%)

78.9

60.9

71.6

50

52.4

Respondents generally agreed that they are comfortable giving informal feedback in

Disagree

(%)

7.1

20.3

12.6

14.9

13.3 teams (78.6%), and are comfortable receiving informal feedback in teams (85.6%).

Respondents also generally agreed that informal feedback improved their group’s teamwork

(74.4%), their group’s final product (80.1%), and their own individual performance (74.5%). (See

Table 2)

Table 2: Exploratory Variables on Informal Feedback

Comfortable giving IFB in teams

Comfortable receiving IFB in teams

IFB improved group's teamwork

IFB improved group's final product

IFB improved individual's performance

Agree

(%)

78.6

85.6

74.4

80.1

74.5

Disagree

(%)

11.4

7.2

8.7

5.6

8.7

17

Bivariate Data

Hypothesis 1: Students that have experience with peer evaluation have better teamwork skills than students that lack experience with peer evaluation.

To analyze the results of our first hypothesis, we first conducted an independent samples t-test to compare the mean teamwork skills score of students with experience with peer evaluation in classroom teams with the mean teamwork skills score of students that lack experience, and found no significant difference between the two groups (t(202) = .814, p > .05).

We found that the majority of students, 59.9% of all respondents, have had experience with peer evaluation while only 9.2% (23) of respondents reported no class or workplace team experience. The overall mean for the Teamwork Skills index is 40.12, while the standard deviation is 3.902. (See Figure 3)

We followed this by using a Chi-Square test of independence to examine the effects that experience with peer evaluation have on teamwork skills. When looking at the assumptions of

Chi-Square tests, several of the items from the teamwork skills index did not have expected frequencies of at least 5 in most of the categories, so we were only able to use Chi-Square tests for items d) I express my thoughts to teammates clearly and respectfully ; e) I can be counted on to help a teammate who needs it ; f) I have a healthy respect for difference and opinions and ways of doing things .

18

Figure 3: Peer Evaluation Experience

19

We calculated a Chi-square test of independence comparing the frequency of expressing thoughts to teammates clearly and respectfully for students who have experience with Peer Evaluation and students without experience. After collapsing the six response categories into agree and disagree, we found no significant interaction (X2(4)=3.661, p> .05).

The skill of expressing thoughts to teammates clearly and respectfully seems to be independent from peer evaluation experience. (See Figure 4)

Figure 4: Express Thoughts to Teammates

20

We calculated a chi-square test of independence comparing the frequency of being counted on to help a team member for students with experience with peer evaluation and students without experience, and found no significant interaction (X2(2)=1.343, p> .05). The skill also seems to be independent from peer evaluation experience. (See Figure 5)

Figure 5: Counted on to Help Teammates

21

We calculated a chi-square test of independence comparing the frequency of being good at helping teammates who disagree find ways to compromise for students with experience with peer evaluation and students with no experience. After collapsing the four response categories into agree and disagree, we found no significant interaction (X2(3)=5.317, p> .05). The skills of helping teammates who disagree find a compromise seems to be independent from peer evaluation experience. (See Figure 6)

Figure 6: Good at Helping Teammates Compromise

22

Hypothesis 2: The more experience students have in teams, the greater the comfort with informal feedback.

To analyze the results of our second hypothesis, we calculated a Spearman rho correlation coefficient for the relationship between the number of class and work teams a student has been in since starting college and comfort giving informal feedback in teams. We found a weak, insignificant correlation showing no relationship (r(2)=.057, p> .05). We then calculated another Spearman rho correlation coefficient for the relationship between the number of class and work teams a student has been in since starting college and their comfort receiving informal feedback in teams. We again found a weak, insignificant correlation (r(2)=-.123, p> .05). The number of class and work teams is independent from comfort giving and receiving informal feedback.

The majority of students, greater than 55% (140), have been in at least five class or workplace teams compared to only 9.2% (23) of respondents who reported no class or workplace team experience. Our results for students who are comfortable giving informal feedback (Mode=6 Median =6) show that 78.5% (165) of students agreed (somewhat to strongly) that they are comfortable giving informal feedback in teams. As for students who are comfortable receiving informal feedback (Mode=6 Median=6), results show that 85.6% (179) of students agreed (somewhat to strongly) that they are comfortable receiving informal feedback in teams. (See Figure 7)

23

Figure 7: Total Team Experience in the Class and Workplace

To explore how peer evaluation experience affects comfort giving informal feedback we calculated a chi-square test of independence comparing students with and without peer evaluation experience with their comfort giving informal feedback, and found no significant interaction (X2(5)=8.182, p>.05).

To explore how peer evaluation experience affects comfort receiving informal feedback we calculated a Chi-square test of independence because frequencies were not above five (with categories of disagree, neutral, and agree). Comparing students with and without peer evaluation experience with their comfort receiving informal feedback, we found no significant interaction (X2(2)=5.569, p>.05).

24

Hypothesis 3: Students that have experience with peer evaluation have a more positive attitude and experience with informal feedback, compared to students without peer evaluation experience.

We analyzed descriptive statistics and found the following: For our independent variable, peer evaluation, 59.9% of respondents said they had past experience with peer evaluation. For our dependent variable, the Informal Feedback Index, we found a mean of 27.13 with a standard deviation of 4.823, which shows that it is heterogeneous. For our bivariate results, we conducted an independent samples t-test comparing the mean score of attitudes towards informal feedback of students who had experience with peer evaluation in classroom teams with the mean score of attitude towards informal feedback of students who lack experience with peer evaluation. We found no significant difference between the two groups (t(190) = 1.220, p > .05).

When we found no statistically significant results, we did further statistical testing of our data. We conducted a chi-square test of independence comparing students’ perception of the extent that team informal feedback improved the following three variables: group's teamwork, team's final product, and an individual's performance for students with or without PE experience.

To explore how peer evaluation experience affects comfort giving informal feedback we calculated a chi-square test of independence comparing students with and without peer evaluation experience with their comfort giving informal feedback, and found no significant interaction (X2(5)=8.182, p>.05).

To explore how peer evaluation experience affects comfort receiving informal feedback we calculated a collapsed chi-square test of independence because frequencies were not above five (with categories of Disagree, Neutral, and Agree). Comparing students with and without peer evaluation experience with their comfort receiving informal feedback we found no significant interaction (X2(2)=5.569, p>.05).

25

We calculated a chi-square test of independence comparing the frequency of teammates' informal feedback improving the group's teamwork for students with experience with peer evaluation and students with no experience with peer evaluation, and found no significant interaction (X2(5)=7.461, p> .05).

We calculated a chi-square test of independence comparing the frequency of teammates' informal feedback improving the team's final product for students with experience with peer evaluation and students with no experience with peer evaluation, and found a statistically significant relationship (X2(5)=11.265, p<.05).

We calculated a chi-square test of independence comparing the frequency of teammates' informal feedback improving an individual’s performance for students with experience with peer evaluation and students with no experience with peer evaluation, and found a statistically significant relationship (X 2 (6)=14.420, p< .05). (See Table 3)

Table 3: Peer Evaluation Experience and Perceived Impact of Informal Feedback

Cramer’s V X 2 P-Value

Group's Teamwork

Team’s Final Product

N/A

.259

1.922

9.583

.383

.008

Individual's Performance .221 13.113 .001

We did a Cramer’s V test comparing the informal feedback for students who did and did not have peer evaluation experience. The Cramer’s V value of .259 shows a moderate association. In conclusion, we found a partially significant relationship for two variables: team's final product and an individual's performance, therefore, we are able to partially support

Hypothesis 3. (See Table 3 above)

26

Discussion

The results from our univariate analysis, showing students’ preferences and attitudes towards types of peer evaluation, may provide instructors with insight on how to better implement these preferred types of peer evaluation in the classroom. Our data also indicate that a majority of college students prefer a peer evaluation form that incorporates both numerical ratings and a section for comments and suggestions. A peer evaluation form done online and outside the classroom was also preferred. This supports prior research findings that discuss how completion of peer evaluations outside of the classroom will have more detailed and well thought out criticisms compared to peer evaluations that are completed in the classroom

(Dommeyer 2006). This is a compelling argument to insist that if an instructor were to have students complete peer evaluation forms they should have their students complete online peer evaluation forms that use numerical ratings and a section for comments outside of the classroom. This supports prior research done by Ohland et. al (2005) that found that adding descriptive instructions on ratings (i.e. excellent, poor) increases the reliability of the peer evaluation because it gave students a clear description of actions and behaviors of these ratings when evaluating peers.

For hypothesis one, we found no statistically significant difference in teamwork skills between students with experience in peer evaluation and students without experience; therefore hypothesis one was not supported. These results indicate that there is no statistical relationship between peer evaluation experience and teamwork skills. Our results showed that the majority of respondents regardless of experience with peer evaluation, stated that they agree that they have the teamwork skills in question. This contradicts McKinney and Denton (2005) who found that peer evaluation helps identify and improve skills that are essential for teams, in that students without peer evaluation reported the same skills. Therefore by itself, peer evaluation doesn’t seem to determine the quality of teamwork skills. We speculate this may be due to

27

respondents being influenced by social acceptability response. This may have caused students to respond more positively when self-reporting their teamwork skills.

For hypothesis two, we found no statistically significant relationship between the presence of past experience in teams and comfort giving or receiving informal feedback.

Furthermore, we found no statistical difference in comfort with informal feedback and peer evaluation experience. Therefore, hypothesis two was not supported. Our results show the majority of students, regardless of team and/or peer evaluation experience, report being comfortable giving (78.5%) and receiving (85.6%) informal feedback. Our findings align with those of Lizzo and Wilson (2008), that students value receiving feedback because it leads to a fair evaluation. Thus, students are overall comfortable, not nervous, to be evaluated as they believe it will be fair. We speculate that the lack of relationship between the two variables explored may be due to self-reported responses that can be influenced by social acceptability, which may have caused the majority of students reporting being comfortable with informal feedback. It would be beneficial to observe behavior instead of using self-reporting.

Our results for hypothesis three found a partially significant relationship between peer evaluation experience and a more positive experience with informal feedback. These results support prior research findings that informal feedback can have a positive influence on improving team memb ers’ performance and work (Larson Jr. 1989). We speculate that having experience with peer evaluation can in turn effectively inform informal feedback skills through having a more concrete and conceptual idea of the kinds of effective teamwork skills and behaviors. For example, when asked to fill out information about peer's skills and teamwork, (i.e. leadership skills, good communication, etc.) perhaps these ideas become imprinted in students’ minds and they begin to employ these ideas in day-to-day, casual interactions with their team members. Especially in the case that informal feedback is sought out by students’ team members, it can be powerful to be able to effectively and eloquently share feedback on team member's performance and work (Larson Jr. 1989).

28

Conclusion

Our research examined the following question about students at a liberal arts college:

Does experience with peer evaluation influence students’ experience with teamwork and informal feedback? Using a questionnaire survey, we examined teamwork skills, comfort with informal feedback, as well as attitude and experience with informal feedback for students with and without peer evaluation experience.

Based on our exploration of our univariate data (i.e. PE attitudes, form/type, etc.), we can report to the Piper Center and instructors that most St. Olaf students prefer to complete an online peer evaluation form outside of the classroom, they prefer forms that use numerical values and written description options, and that most St. Olaf students agreed that peer evaluations should be used regularly in class. Instructors could implement more online peer evaluation forms for their students to evaluate group work if needed.

Our results did not find any support for our first two hypotheses: that students that have experience with peer evaluation have better teamwork skills than students who lack experience with peer evaluation, and the more experience students have in teams, the greater the comfort with informal feedback.

Our third hypothesis was partially supported. We found a statistically significant difference between students with peer evaluation experience and students without on their experience with informal feedback improving their team’s final product and individual’s performance. Thus, using peer evaluation may help students effectively use informal feedback.

We did not find a statistically significant difference depending on peer evaluation experience level for their attitude towards informal feedback.

In light of our results, we would recommend that instructors and professors use peer evaluation in teams to improve students’ experience with informal feedback. Professors might use peer evaluation forms that give students skills to later be able to evaluate their peers in a more informal setting. Because Larson Jr. (1898) and Arnold et al. (2005) suggest that informal

29

feedback is an easier interaction for team members and has a positive influence on team members’ work, we believe students may benefit from having professors give them guidance in doing informal feedback in a constructive, articulate manner. We would also recommend that career advising centers encourage professors to use peer evaluation as a way to improve informal feedback, as this can be a critical skill in the workplace setting after college.

Our sample population, consisting of students from a small Midwestern liberal arts college, limits our ability to relate our results beyond our small sample size to the greater population. Additionally, because students did self-report, our survey results may be limited.

Self-reporting could have lead to social acceptability bias, where students select responses based on what is most socially acceptable. Another limitation is that we used a combined survey with other research groups, limiting the questions we could ask, and thus inhibiting us from examining our hypotheses in depth. Because the survey was shared among groups, the compiling of questions resulted in a length that may discourage students from taking the survey.

Future research could examine whether the relationship between peer evaluation and a positive experience with informal feedback found is due to a change in students’ behavior or simply to increased awareness. We question whether students have had a behavioral change with informal feedback due to peer evaluation or because their awareness is increased due to their peer evaluation experience. This future research may enable researchers to examine why this relationship exists.

30

REFERENCES

Aritzeta, A., Sabino Ayestaran, and Stephen Swailes. 2005. “Team Role Preference and

Conflict Management Styles.” International Journal of Conflict Management 16.2: 157-82.

Arnold, Louise, Shiphra Ginsburg, Barbara Kritt, Carolyn K. Shue, and David Stern. 2005.

“Medical Students' Views on Peer Assessment of Professionalism.” JGIM: Journal of

General Internal Medicine 20(9). Retrieved September 15, 2012.

(http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=7&hid=14&sid=1f7c41ba-1f30-4e6c-9b15-

2377de4ae2be%40sessionmgr13&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=ap h&AN=17947302).

Buljac-Samardzic, M., van Wijngaarden, J. D. H., van Wijk, K. P., van Exel, N. J. A. 2011.

“Perceptions of team workers in youth care of what makes teamwork effective.” Health and Social Care in the Community 19.3: 307-316.

Bowes-Sperry, Lynn, Deborah L. Kidder, Sharon F oley, and Anthony F. Chelte. 2005. “The

Effect of Peer Evaluations on Student Reports of Learning in a Team Environment: A

Procedural Justice Perspective.” Journal of Behavioral & Applied Management 7(1).

Retrieved September 19, 2012.

(http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=7&sid=884dfc81-0f03-4730-9156-

021deee60b95%40sessionmgr10&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=ap h&AN=19164166).

Chen, ChaoChien. 2010. “Leadership and Teamwork Paradigms: Two Models for Baseball

Coaches”. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal 38(10). Retrieved

October 7, 2012.

(http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=14&sid=d91a2a23-c680-46a1-a86b-

45969b233cda%40sessionmgr15&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=ap h&AN=55114704)

31

Dommeyer, Curt J. 2006. "The Effect of Evaluation Location on Peer Evaluations." Journal of

Education for Business 82(1). Retrieved September 17, 2012.

(http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=1176fc8c-231e-40ac-83bf-

0a8562492444%40sessionmgr12&vid=9&hid=14).

Foster, Niall and Pat Wellington. 2009. "21st Century Teamwork." Engineering & Technology

4(18). Retrieved September 7, 2012.

(http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=21&sid=7f04b005-90cd-45c8-84bec8b8275d3151%40sessionmgr10&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=ap h&AN=46708435).

Institutional Review Board 2010. “Who Needs to Review my Project?” Northfield,

MN: St. Olaf College Institutional Review Board. Retrieved December 7, 2011

(http://www.stolaf.edu/academics/irb/Policy/WhoReviews.pdf).

Larson Jr., James R. 1989. "The dynamic interplay between employees' feedback-seeking strategies and supervisors' delivery of performance feedback." Academy of Management

Review . Retrieved October 25, 2012.

(http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/258176?uid=3739736&uid=2&uid=4&uid=373925

6&sid=21101359821107)

Lizzio, Alf and Keithia Wilson. 2008. “Feedback on Assessment: Students’ Perceptions of

Quality a nd Effectiveness.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 33(3).

Retrieved October 3, 2012.

(http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=ef9691fe-b333-4c40-9065-

888851091e70%40sessionmgr111&vid=9&hid=106).

Long, Cheng, Wang ZhongMing, and Wei Zhang. 2011. “The Effects of Conflict on Team

Decision Making.” Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal 39(2).

Retrieved October 7, 2012.

(http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=8&hid=13&sid=4e7b071a-9a96-4efc-a164-

32

03032ed59c08%40sessionmgr14&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=ap h&AN=59694470).

Marls, Michelle A.. and Frederick J. Panzer. 2004. “The Influence of Team Monitoring on Team

Processes and Performance .” Human Performance 17(1). Retrieved on September 14,

2012. (http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=21&sid=30275724-442b-

4b2c85707a2c03a60f9f%40sessionmgr11&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3 d#db=aph&AN=12286774).

McKinney, D., & Denton, L. F. 2005. “Affective assessment of team skills in agile CS1 labs: the good, the bad, and the ugly.” ACM SIGCSE Bulletin 37 (1). Retrieved October 25, 2012.

(http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1047494).

Neuman, W. Lawrence. 2012. Basics of Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative

Approaches, 3rd ed.

New York, NY: Allyn & Bacon.

Ohland, Matthew W., Richard A. Layton, Misty L. Loughry, and Amy G. Yuhasz. 2005. "Effects of Behavioral Anchors on Peer Evaluation Reliability." Journal of Engineering Education

94(3). Retrieved October 5, 2012.

(http://search.proquest.com/docview/217949172?accountid=351; http://br6hl4gz8p.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-

2004&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-

8&rfr_id=info:sid/ProQ%3Apqrl&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&rft.genre=article

&rft.jtitle=Journal+of+Engineering+Education&rft.atitle=Effects+of+Behavioral+Anchors+ on+Peer+Evaluation+Reliability&rft.au=Ohland%2C+Matthew+W%3BLayton%2C+Richa rd+A%3BLoughry%2C+Misty+L%3BYuhasz%2C+Amy+G&rft.aulast=Ohland&rft.aufirst=

Matthew&rft.date=2005-07-

01&rft.volume=94&rft.issue=3&rft.spage=319&rft.isbn=&rft.btitle=&rft.title=Journal+of+En gineering+Education&rft.issn=10694730).

33

Patten, Mildred L. 2011. Questionnaire Research: A Practical Guide, 3rd ed. California: Pyrczak

Publishing.

Tseng, Sheng-Chau, and ChinChung Tsai. 2010. “Taiwan College Students’ Self-efficacy and

Motivation of Learning in Online Peer Assessment Environments.” Internet and Higher

Education 13(3). Retrieved October 3, 2012.

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S109675161000014X).

Towry, Kristy L. 2003. “Control in a Teamwork Environment: The Impact of Social Ties on the

Effectivenes s of Mutual Monitoring Contracts.” The Accounting Review 78(4). Retrieved

September 15, 2012. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/3203291).

Wen, Meichun L., and ChinChung Tsai. 2006. “University Students' Perceptions of and

Attitudes toward (Online) Peer Assessment”. Springer 51(1). Retrieved September 15,

2012. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/29734964).

34