File

advertisement

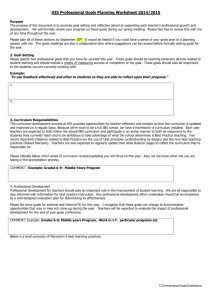

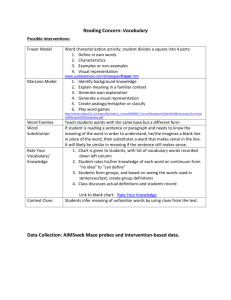

Please sit at a table in groups of four. Vocabulary! Workshop 1: Why Teaching Academic & Content Vocabulary is Necessary At Your Tables of 4. . . 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Each person should take one of the sheets of paper from the middle. Each paper has a word and an explanation/description sentence printed on it. One person should read the word and the sentence out loud to the group. If someone doesn’t understand the description sentence, ask the group and discuss the meaning. List three examples of that word on the sheet. Pass your sheet to the next person. Write a sentence using the word that shows you understand the meaning of the word. Pass the sheet. Sketch a picture to illustrate the meaning of the word or to help you remember it. Pass the sheet. Rate your understanding of your word from level 1 (low) to level 4 (high). Choose the elements you think are the best/most accurate from the group work. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3l4g5QWEgVI Monty Python – Language Lab Just like we have different registers for different social situations . . . Monty Python – Language Lab . . . we have very different sets of vocabulary for different academic situations. Have you ever . . . . . . felt like your students organize their idea library randomly, like colour coding? It looks tidy, but they can’t find what they’re looking for? Or, maybe the ideas in their library are just shells – like someone made a bunch of cardboard book covers that looked vaguely like the originals and stuck them, empty, up on the shelf. It looks good at first, but when they want to take an idea off the shelf, it crumples in their hands. http://www.yofx.org/?cat=1 For our students, all problems are word problems. Why Teaching Academic AND Content Vocabulary is Necessary “Academic background knowledge affects more than just ‘school learning’” (Marzano 3) It also affects occupation, income, status, power. More importantly, the ability to learn and make decisions in highly verbal contexts is defined by the amount of academic background knowledge one has. information in our permanent memories (fluid, innate, natural intelligence) 2.The number and frequency of our academic experiences (crystalized, learned intelligence) (Marzano 4-5, 13) High Medium 1.Our ability to store and process Low Through the interaction of two factors: Information-Processing Ability How do we get Background Knowledge? Access to Academically Oriented Experiences Low Medium High Delbert Barbara Allen Gina Ian Calvin Iris Hilda Frank (Marzano 6) At school, we can affect BOTH a student’s fluid and crystallized intelligence. 1.We provide them with direct (real) and virtual life experiences in all subject areas. 2.We provide them with the tools to learn how to learn. Permanent Memory Working Memory We experience stuff through our senses all the time. We choose to pay attention to and make sense of the stuff we have had the most experience with. The more often we encounter stuff with which we are familiar, the more often our associated memories are activated, settling that information more and more into our permanent memory. Voila! Background Knowledge! (Marzano 22) Making it STICK. Basically, the more often a student has experiences with a concept, the more likely it will be to become permanent memory. Sensory Memory Permanent Memory Working Memory Sensory Memory (Marzano 35) Making it STICK. The best way to increase background knowledge is through a high quantity of high quality, direct experiences. Provide a Framework: Community & Service: Coal Bank Christmas Service Week Fundraising Noori Direct Experiences Create General Background Knowledge Academic Experiences: Field Trips Visiting Experts But schools are limited in their ability to provide these. 1. Educational Television 2. Language Interaction: Virtual Experiences Create General Background Knowledge “When we describe our camping trip to a friend, that friend translates our words into working memory representations. The more we talk to our friend about our camping trip, the more our friend’s background knowledge of camping trips expands. . . . The more students talk and listen to others, the more virtual experiences are generated” (Marzano 39). 3. Wide Reading: “our sensory memory is filled with images . . . we create a virtual representation of the camping trip in working memory. . . . for all practical purposes the same as the direct experience” (Marzano 36). Less reading = less vocabulary = less reading = less background knowledge average 5th grade reader = 650,000 Avid 5th grade reader = 5,850,000 Extremely avid readers encounter 200 times more words than disinterested readers. staggering individual differences in the volume of language experience, = fewer opportunities to learn new words = less desire to read = fewer opportunities (Anderson, Wilson, and Fielding in Marzano 37). . How else can we help our students bulk up their internal encyclopedia? LABEL Direct Vocabulary Instruction Creates General Background Knowledge Positive Effects of Direct Vocabulary Instruction 83 62 50 (Stahl & Fairbanks in Marzano 69) The Differences between Academic and Content Vocabulary 1. Academic Vocabulary – test-taking words. The kinds of words that often appear in the instructions for an assessment task in multiple subject areas: analyse, illustrate, identify, expose, explain, prove, compare, contrast, examine, etc. 2. Content Vocabulary – words peculiar to one subject area: metaphor, parliament, trigonometry, photosynthesis, puberty, etc. Choosing Academic Vocabulary Sit with your grade level team. Read through several on-line lists for terms you and your team often use in class and on assignments. http://www2.elc.polyu.edu.hk/CILL/eap/wordlists.htm www.englishcompanion.com/pdfDocs/acvocabulary2.pdf http://www.victoria.ac.nz/lals/resources/academicwordlist/sublists. aspx Record these words on the handout on Googledocs. Indicate for which grade level you are recording these. Choosing Academic Vocabulary Move to a reading centre that interests you: 1.Academic terms found on external standardized assessments Read through the International Schools’ Assessment (ISA), PSAT, and other examples of standardized tests. Write a list of academic terms students encounter there. 2. Academic terms found on internal assessments and materials Read through in-school, grade level assessments (teachers bring these with them) to find academic terms students need to know for their grade level. Take a look at your textbooks and test-generating resources. 3. Academic terms found in the MYP Subject Aims and Objectives Read through the MYP Course Aims and Objectives to find academic terms Record these words on the handout on Googledocs. Indicate, when possible, for which grade level they seem most appropriate. The Googledoc will remain open to all of you after the workshop, so feel free to keep adding to the lists until the next workshop. How Many Words? 400 words (less for ELLs!) per school year become part of their working vocabulary (Julie Adams). Choose WISELY. How Many Words? Rule of Thumb: For each subject area The number of words equal to the student’s grade in school. Students max out at 10 words. Choose WISELY. How Many Words? Rule of Thumb: Grade 6: 6 words per subject per week. But some subjects have many more words than others Choose WISELY. What about Content Vocabulary? ... That’s a discussion we’ll save for Workshop #2! How Do I Teach This Stuff? According to Marzano, there are 6 Steps to Direct Vocabulary Instruction. ... That’s a discussion we’ll save for Workshop #3! Marzano, Robert J. Feldman, Kevin, & Kate Kinsella http://www.fcoe.net/ela/pdf/Vocabulary/Narr owing%20Vocab%20Gap%20KK%20KF%201.pd f Works Cited: Adams, Julie