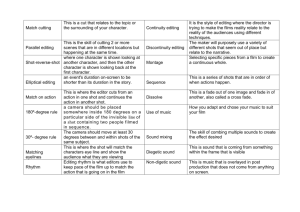

Camera Movements, Editing & Sound: Film Techniques Guide

advertisement

Camera Movement – Editing – Sound This isn’t so much a guide, more of a walk through most of the more common camera movements and edits used in film. Remember that just like with the framing it’s not enough to just spot and name, you must discuss potential effects of technical codes. Think about why the film maker did what they did. You should also remember that shots, moves and edits don’t work as a single action. Their meaning is made by their relation to every other element. That’s kind of an excuse as to why this such a mixed up glossary. JUMP CUT The jump cut is hard to describe without seeing it in action. It’s a jarring edit where the middle part of a continuous action is cut out. As with so many editing techniques, Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein helped define the jump cut. It was brought to prominence in modern film with the start of the French New Wave with the release of Breathless (1960) by director Jean-Luc Godard. In the scene look out (and listen for) the bit where the bike runs past Patricia. SMASH CUT A smash cut is a cut whose purpose is to be startling to the viewer. The transition between shots is abrupt, drawing attention to the cut and shaking things up. The German documentarian Leni Riefenstahl helped pioneer its use. Some famous examples include the abrupt cuts to black in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) and in The Bourne franchise. MATCH CUT A match cut is a cut that joins two unrelated shots together in a way that makes them seem related. Often this means cutting between two moving objects with similar trajectories — famously, a spinning bone cuts to a spinning space station at the start of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) — or between two objects with similar shapes, or between shots with similar composition. The match cut is useful as an editing tool because it asks the audience to directly compare two images that may or may not have any direct narrative connection. Match cuts can also be used to cut between similar sounds, such as between a scream and a rumbling subway car. Match cuts can also be smash cuts at the same time if their effect is to startle. The famous smash cut cliche of cutting between a knife about to enter flesh and a kitchen knife chopping meat is an example of a match cut and a smash cut, because both scenes are linked through visual and audio similarities. This is fairly typical of early horror films, before Romero started extending what could be done with special effects. AXIAL CUT A type of jump cut, where the camera suddenly moves closer to or further away from its subject, along an invisible line drawn straight between the camera and the subject. While a plain jump cut typically involves a temporal discontinuity (an apparent jump in time), an axial cut usually doesn’t. Stanley Kubrick loves this type of cut as do video directors. LONG TAKE This is an uninterrupted shot in a film which lasts much longer than the conventional editing pace either of the film itself or of films in general, usually lasting several minutes. It can be used for dramatic and narrative effect if done properly, and in moving shots is often accomplished through the use of a dolly or Steadicam. The term "long take" is used because it avoids the ambiguous meanings of "long shot", which can refer to the framing of a shot, and "long cut", which can refer to either a whole version of a film or the general editing pacing of the film. However, these two terms are sometimes used interchangeably with "long take". When filming Rope (1948), Alfred Hitchcock intended for the film to have the effect of one long continuous take, but the cameras available could hold no more than 1000 feet of 35 mm film. As a result, each take used up to a whole roll of film and lasts up to 10 minutes. Many takes end with a dolly shot to a featureless surface (such as the back of a character's jacket), with the following take beginning at the same point by zooming out. The entire film consists of only 10 shots. Long takes are a favourite of Martin Scorsese, see Goodfellas. FAST CUTTING This is a film editing technique which refers to several consecutive shots of a brief duration (e.g. 3 seconds or less). It can be used to convey a lot of information very quickly, or to imply either energy or chaos. See the Bourne extract for a good example. Fast cutting is also frequently used when shooting dialogue between two or more characters, changing the viewer's perspective to either focus on the reaction of another character's dialog, or to bring to attention the non-verbal actions of the speaking character. Fast cutting is often found in Music video. CONTINUITY EDITING AND SOME DEGREES OF SEPARATION Continuity editing uses a guideline called "the 30 degree rule" to avoid jump cuts. The 30 degree rule advises that for any consecutive shots, the camera position vary at least 30 degrees from the previous position. Generally, if the camera position changes 30 degrees or more, the spectator experiences the edit as a change in camera position rather than a jump in the position of the subject. Although jump cuts can be created through the editing together of two shots filmed noncontinuously, they can also be created by removing a middle section of one continuously-filmed shot. The 180° rule is a basic guideline in film making that states that two characters (or other elements) in the same scene should always have the same left/right relationship to each other. If the camera passes over the imaginary axis connecting the two subjects, it is called crossing the line. The new shot, from the opposite side, is known as a reverse angle. In professional productions, the applied 180° rule is an essential element for a style of film editing called continuity editing. The rule is not always obeyed. Sometimes a filmmaker will purposely break the line of action in order to create disorientation. Stanley Kubrick was known to do this but the pioneer was Japanese director Ozu. FADE, DISSOLVE, WIPE All three of these editing techniques are slow transitions between shots, less abrupt than a cut. A fade comes in two varieties: a fade-in and a fade-out. A fade-in starts from a solid color screen (usually black, but sometimes white and rarely other colors) and slowly transitions to a shot in the movie, as the shot is superimposed over the solid screen. A fade-out starts with a shot and transitions to a solid color. The term “fade to black” denotes the traditional way of ending a movie. In addition to opening and closing films, fades are often used within a movie to denote the passage of time. If several fades are used to transition between short scenes, it creates a very dreamlike atomsphere. A great extra on the Fight Club (1999) DVD offers an example of how fades can affect the way we view sequences. The screen wipe is the least-used of these techniques, and is thus the most obvious. Probably best known today from the Star Wars movies (though when George Lucas used this technique it was mainly an homage to Akira Kurosawa), the wipe has one image replace another through some sort of movement. Wipes are particularly abused by home movie makers with easy access to video editing software but little sense of style. Take not for coursework. In the Breathless extract you’ll find an iris wipe. This is where a scene fades into or out of a whole in black screen. It’s usually found in silent era films. POV A point of view shot shows what a character (the subject) is looking at (represented through the camera). It is usually established by being positioned between a shot of a character looking at something, and a shot showing the character's reaction (see shot reverse shot). The technique of POV is one of the foundations of film editing. A POV shot need not be the strict point-of-view of an actual single character in a film. Sometimes the point-of-view shot is taken over the shoulder of the character (third person), who remains visible on the screen. Sometimes a POV shot is "shared" ("dual" or "triple"), i.e. it represents the joint POV of two (or more) characters. There is also the "nobody POV", where a shot is taken from the POV of a non-existent character. This often occurs when an actual POV shot is implied, but the character is removed. Sometimes the character is never present at all, despite a clear POV shot, such as the famous "God-POV" of birds descending from the sky in Alfred Hitchcock's film, The Birds. A POV shot need not be established by strictly visual means. The manipulation of diegetic sounds can be used to emphasize a particular character's POV. It makes little sense to say that a shot is "inherently" POV; it is the editing of the POV shot within a sequence of shots that determines POV. Nor can the establishment of a POV shot be isolated from other elements of filmmaking — mise en scene, acting, camera placement, editing, and special effects can all contribute to the establishment of POV. The Saving Private Ryan sequence has some excellent POVs. EYELINE MATCH An eyeline match is a popular editing technique associated with the continuity editing system. It is based on the premise that the audience will want to see what the character on-screen is seeing. The eyeline match begins with a character looking at something off-screen, there will then be a cut a point of view shot. Look out for them in the Saving Private Ryan extract. SHOT REVERSE SHOT (OR SHOT/COUNTERSHOT Pretty much where one character is shown looking at another character (often off-screen but sometimes it can be an over the shoulder shot), and then the other character is shown looking back at the first character. Since the characters are shown facing in opposite directions, the viewer assumes that they are looking at each other. Shot reverse shot is a feature of the "classical" Hollywood style of continuity editing, which deemphasizes transitions between shots such that the audience perceives one continuous action that develops linearly, chronologically, and logically. It is in fact an example of an eyeline match. The scene in Heat is a great example where the growing intimacy of the two characters is shown with reverse cuts into closer frames. COLD OPEN The cold open is a simple but effective way to start a story: just start telling it without any other fanfare. A movie is said to have a cold open if we begin seeing the story before the opening credits. Almost unheard of since the earliest days of films — when movies had no credits, period — George Lucas opened Star Wars (1977) with a mostly cold open. That film opens with a title screen, but no credits, and launches right into the story. Lucas’ decision to open The Empire Strikes Back (1980) in the same way over the protests of the writers’ and directors’ unions led to his resignation from those organizations. Since then, the move has become increasingly common, though generally films still have some kind of credit scene at the beginning. For instance, the James Bond movies begin with an action sequence before the credits. Almost every modern American television show eschews opening credits together, starting with a cold open and then a short title scene. See it in the Bourne extract. TRACKING SHOT A tracking shot is a camera movement where the entire camera is mounted to a cart of some sort and the cart runs on tracks laid on the ground. The cart and the camera are pushed along the track, creating a very smooth movement (contrast it to the much less smooth handheld shot). The term “dolly shot” is often used as a synonym for tracking shot, as the cart the camera is placed on is a dolly. If you read screenplays or hang around film geeks, you will find references to camera movements such as “dolly in” or “push out,” and these generally refer to a tracking shot that moves the camera toward or away from the subject of the shot. Tracking shots are generally expensive to set up. Laying track takes time and whenever you move the camera around in an unbroken shot everything about shooting a scene is more complicated. Thus, generally directors like to reserve them for fancy moves. Often tracking shots are quite long, and many of the most celebrated shots in the movies are extended tracking shots. There’s a great tracking shot in the Goodfellas sequence. CRANE, HANDHELD A crane shot is a camera movement achieved by putting the camera on a platform mounted to a crane. It allows the camera to swoop up and down and in and out, achieving fantastic points of view that would never be possible were the camera stuck on the ground. Crane shots are very flashy and can be combined with tracking shots to create unbroken shots that are as dazzling as they are impossible-seeming. A handheld shot is a camera move that is nowhere near as fluid as a tracking shot or a crane shot. Instead, handheld shots are shots where the camera is held by a camera operator. This allows the camera to move anywhere a cameraman can carry it, but without anything to stabilize the camera the shot becomes very jerky. Despite technology that allows directors to achieve the freedom of handheld shots without the shakiness, many directors enjoy handheld shots for their immediate feel. Documentaries have long used handheld shots, and so directors of narrative films employ handheld shooting to achieve a documentary feel. Watch the Bourne extract and Saving Private Ryan for excellent hand held sequences. PAN, TILT A pan is a camera movement that involves the camera moving along a horizontal axis, i.e., it moves sideways. If you have a camera on a tripod and you swivel the camera from left to right, you have panned it. A tilt is the same idea, but vertically (so up and down). These are very common moves that are significantly easier to shoot than shots where the camera actually moves around, and they also have a more distant feel to them. See the Battle of Algiers pan. ZOOM The zoom is a type of lens that can go from wide to long, allowing film shots to make distant objects suddenly look closer (or vice versa). To zoom in is to make distant objects look closer; to zoom out is to do the opposite. This is not technically a camera movement; it’s a method of changing the audience’s point-of-view without actually moving the camera or cutting. Zoom lenses were around in some fashion for much of cinema history, but it wasn’t really until the 1960s that they were of a quality to be used regularly in film productions. Zooming tends to change the depth of field, allowing more objects to be in focus at once while wide and fewer objects in focus while long (though there are ways this can be manipulated so that long shots still have a large of depth of field). The zoom is a very showy move that has a documentary feel to it, because filmers of documentaries have to zoom in order to capture unexpected events. The 1970s made the zoom a staple of American filmmaking, and directors like Robert Altman love the zoom for its ability to hold a long shot but to suddenly focus in on a single character or object. Stanley Kubrick loved to zoom in on the faces of his actors such that they almost overpowered the entire frame. A classic sort of zoom involves starting with a crowd of people and then zooming in on a small group; we start with an establishing shot to understand the environment and then seamlessly move in. This has a subtly different effect than pushing in on an object, because the unique way zoom lenses work distorts things in a way that seems vaguely unnatural to the human eye. Crash zooms are fast zooms from a wide to close shot. They’re usually found with handheld like in the Bourne sequence but you can also see on in the Goodfellas extract. If you use one for your coursework you’ll need a very good reason, it’s hard to get right. CONTRA/DOLLY Z OOM A technique in which the camera moves closer or further from the subject while simultaneously adjusting the zoom angle to keep the subject the same size in the frame. The dolly zoom effect is an unsettling in-camera special effect that appears to undermine normal visual perception in film. The effect is achieved by using the setting of a zoom lens to adjust the angle of view (often referred to as field of view) while the camera dollies (or moves) towards or away from the subject in such a way as to keep the subject the same size in the frame throughout. In its classic form, the camera is pulled away from a subject whilst the lens zooms in, or vice-versa. Thus, during the zoom, there is a continuous perspective distortion, the most directly noticeable feature being that the background appears to change size relative to the subject. As the human visual system uses both size and perspective cues to judge the relative sizes of objects, seeing a perspective change without a size change is a highly unsettling effect, and the emotional impact of this effect is greater than the description above can suggest. The visual appearance for the viewer is that either the background suddenly grows in size and detail overwhelming the foreground; or the foreground becomes immense and dominates its previous setting, depending on which way the dolly zoom is executed. The effect was first developed by Irmin Roberts (a 2nd unit cameraman) not, as is often claimed, Alfred Hitchcock. The most famous examples are found in Spielberg’s Jaws and Hitchcock’s Vertigo but I like the one in Goodfellas. DIEGETIC AND NON-DIEGETIC SOUND Diegetic sound is sound you would expect to hear in the world of the film, a door slamming for example. Non-Diegetic sound is unnatural to this world, for example a voiceover or music. A good example is Henry’s voiceover in Goodfellas or the computer noise of the captions in the Bourne sequence. ASYNCHRONOUS SOUND This is sound, either diegetic or non-diegetic, that runs over an edit. For example in the Goodfellas extract the conversation between the FBI men and Henry begins in the previous diner scene. His non-diegetic voiceover also runs over edits. It’s a very effective way of adding meaning or drama to a shot.