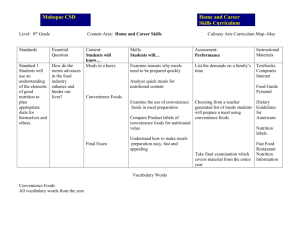

Acknowledgements - Department of Social Services

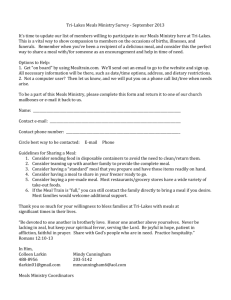

advertisement