Partial factor tax

advertisement

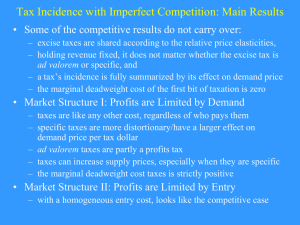

Session 6 Taxation and income distribution Introduction • Is the tax burden distributed fairly? • Statutory Incidence : indicates who is legally responsible for a tax. • Normally the statutory incidence is on the seller. • But the situation differ with respect to who really bears the burden.. • Prices may change in response to the tax. 14-2 Economic Incidence • It is the change in distribution of real income induced by a tax. • The main focus in this session is on tax shifting. • Tax shifting is the difference between statutory incidence and economic incidence 14-3 Tax Incidence: General Remarks • Only people can bear taxes – Functional distribution of income: People’s role in production used to classify tax incidence. E.g. capitalists, labourers and landlords classification according to the inputs they supply to the production process (this is considered oldfashioned) – Size distribution of income: Looks at how taxes affect the way that total income is distributed across income classes. 14-4 Tax Incidence: General Remarks • Both sources and uses of income should be considered • For instance if a tax reduces the demand for cigarettes, the factors employed in cigarettes production may suffer income losses. • Incidence depends on how prices are determined: different models of price determination may give different answers to the question of who really bears the burden. • The SR and LR incidence of a tax may differ. 14-5 Tax Incidence: General Remarks Incidence depends on the disposition of tax revenues: • Balanced-Budget tax incidence: computes the combined effects of levying taxes and govt spending financed by those taxes • The idea is to determine how incidence differs when one tax is replaced with another, holding the govt budget constant (differential tax incidence). A lump-sum tax is often used as the basis of comparison. • Lump sum tax: is a tax whose value is independent of the individual’s behaviour. • Absolute tax incidence: examines the effects of a tax when there is no change in either other taxes or govt expenditure14-6 Tax Progressiveness Can Be Measured in Several Ways • Average tax rate: Ratio of taxes paid to income • Marginal tax rate: the proportion of the last dollar of income taxed by the govt. • Proportional tax system(flat-rate income tax): A tax system under which an individual’s average tax rate is the same at each level of income. • Progressive tax system: an individual’s average tax rate increases with income. • Regressive tax system: an indiv’s avg tax rate decreases with income. 14-7 Tax Progressiveness Can Be Measured in Several Ways Tax Liabilities under a hypothetical tax system Income Tax Liability Average Tax Rate Marginal Tax Rate $2,000 -$200 -0.10 0.2 3,000 0 0 0.2 5,000 400 0.08 0.2 10,000 1,400 0.14 0.2 30,000 5,400 0.18 0.2 14-8 Measuring How Progressive a Tax System Is v1 T1 I1 T0 I0 I1 I 0 14-9 Tax Progressiveness Can Be Measured in Several Ways • The greater the increase in avg tax rates as income increases the more progressive is the system. v1 is the formula for measurement of progressiveness • T0 and T1 are the true tax liabilities at income I0 and I1 respectively. I1 >I0. • The tax system with the highest v1 is more progressive. • The second measure of progressiveness is to say that for a more progressive tax system, its elasticity of tax revenue with respect to income is higher. V2 is the elasticity formula. 14-10 Tax Progressiveness Can Be Measured in Several Ways v2 T1 T0 T0 I1 I 0 I0 14-11 Tax Progressiveness Can Be Measured in Several Ways • Assume that T0 = 200 and T1 = 300 and also assume that I0 = 800 and I1= 1000 respectively. • Now consider the following proposal: Everyone’s tax liability is to be increased by 20% of the amount of tax he or she currently pays. The new tax liabilities are T0 = 240 and T1 = 360 and also assume that I0 = 800 and I1= 1000 respectively. 14-12 Measuring How Progressive a Tax System is – A Numerical Example v1 T1 I1 T0 I0 v2 I1 I 0 .00025 1000 800 300 1000 200 800 .0003 1000 800 360 1000 240 800 T1 T0 T0 I1 I 0 I0 2.0 300 200 200 1000 800 800 2.0 360 240 240 1000 800 800 14-13 Tax Progressiveness Can Be Measured in Several Ways • V1 increases by 20% meaning the proposal increases progressiveness. • V2 is unchanged. • This implies that measures of progressiveness can give different answers 14-14 Partial Equilibrium Models • Models that study only one market and ignore possible spill over effects in other markets. • The main question is how taxes affect income distribution. • The main tool of analysis is the ss and dd model. 14-15 Unit taxes on commodities • Unit tax: is a tax levied as a fixed amount per unit of the commodity purchased. • E.g. if govt imposes a tax of 10 cents per litre of petrol. • A unit tax changes the dd curve as perceived by suppliers. The new dd curve is located below the old one by the magnitude of the unit tax. • The equilib is where the ss equals dd as perceived by the suppliers • The tax lowers the quantity sold from 4 to 3. • There are two prices to consider: the price perceived by producers and the price paid by consumers. 14-16 $ 2.60 Partial Equilibrium Models 2.40 2.20 Before Tax After Tax Consumers Pay $1.20 $1.40 Suppliers Receive $1.20 $1.00 S1 2.00 S0 1.80 1.60 1.40 1.20 1.00 0.80 D0 0.60 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 D1 7 Quantity 8 14-17 Unit taxes on commodities • The price received by producers is at the intersection of their effective dd and ss curves (P = $1.00). • The consumers pay $1.00 plus the unit tax. • This is = $1.40. This is called the price gross of tax. $1.00 is the price net of tax. • The tax makes consumers worse off but the consumer’s price does not increase by the full amount of the tax. • Producers also pay part of the tax ( in our case it’s a 50-50 situation). They are also worse off. 14-18 Unit taxes on commodities The incidence of a Unit tax is independent of whether it is levied on consumers or producers. • Suppose the same unit tax is levied on suppliers of champagne. • The supply curve as it is perceived by consumers must shift up by the amount of the unit tax to S1. • The posttax equilibrium is at 3 and the price at the intersection($1.40) is paid by consumers. • The price received by producers is $1.00. 14-19 Unit taxes on commodities • What matters is the size of the disparity the tax introduces between the price paid by consumers and the price received by suppliers and not on which side of the market the disparity is introduced. • The tax induced difference between the price paid by the consumers and the price received by producers is called the Tax Wedge 14-20 Unit taxes on commodities The incidence of a unit tax depends on the elasticities of ss and dd • A unit tax on a good that has perfectly inelastic ss causes the price received by the producers to fall by exactly the amount of the tax. – Producers bear the entire burden of the tax • A unit tax on a good that has perfectly elastic ss causes the price paid by the consumers to increase by exactly the amount of the tax. – The consumers bear the tax burden. 14-21 $ 2.6 SX 2.4 2.2 2 1.8 1.6 tax 1.4 1.2 DX 1 Perfectly Inelastic D ’ Supply X 0.8 DX1 0.6 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Quantity 8 14-22 $ 2.6 2.4 2.2 2 1.8 1.6 Perfectly Elastic Supply 1.4 tax SX 1.2 1 DX 0.8 DX’ DX1 0.6 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Quantity 8 14-23 Ad Valorem Taxes • A tax computed as a % of the purchase value. • For example 10% tax (VAT) on the purchase of food in SA. • Ad valorem taxes are often levied on luxuries. • The analysis of an ad valorem tax is similar to that of a unit tax. • The basic plan is to find out how the tax changes the effective dd curve and compute the equilibrium. • The ad valorem tax however lowers the curve down by the same proportion(%) which is a swivel rather than a parallel shift. 14-24 Price per Pound of food Ad Valorem Taxes Sf Pr Pc P0 Ps Pm Df Df’ Qr Qn Q0 Qm Pounds of food per year 14-25 Ad Valorem Taxes • An ad valorem tax on consumers shifts the dd curve down by the same proportion at each level of output. • Df’ is the effective dd curve faced by suppliers. • Df is the original dd curve. • The equilibrium is where Sf and Df’ intersect. • The incidence will be determined by the elasticities of supply and demand. • Pc is the price paid by consumers and Ps is the price received by suppliers. 14-26 Taxes on Factors: The Payroll Tax • A similar analysis can be applied to factors of production. • The Payroll Tax:is paid from the employer's own funds and that is directly related to employing a worker, which can consist of a fixed charge or be proportionally linked to an employee's pay. • If the labour ss is perfectly inelastic, a payroll tax causes the wage received by workers to fall by the exact amount of the tax. Workers bear the entire burden 14-27 Wage rate per hour The Payroll Tax SL Pr wg = w0 wn DL DL’ L0 = L1 Hours per year 14-28 Taxes on Factors : Capital Taxation in a Global Economy • In a closed economy the dd is downward sloping and the ss is upward sloping. • Therefore the owners of capital bear some burden of a tax on K. This depends on elasticities of dd and ss. • In an open economy where capital is perfectly mobile the ss of K to a country is perfectly elastic. • The before-tax price paid by the users of K rises by exactly the amount of the tax. • Suppliers of K bear no burden. • K moves abroad if it has to bear any of the tax. 14-29 Commodity Taxation without Competition: Monopoly • If a unit tax is levied on a product, the effective dd curve and MR curve facing the monopolist shift down by a vertical distance equal to the tax. • The profit-maximising output is found at the intersection of the new MR curve and the MC curve. • The tax reduces the equilib quantity from X0 to X1 and increases the price paid by consumers from Po to Pg. • The price received by the producer decreases from Po to Pn and decreases the monopoly profits. 14-30 Monopoly $ Economic Profits Pg c P0 Pn i dh MXX a f g Economic Profits after unit tax ATCX b ATC0 DX MRX X1 X0 MRX’ DX’ X per year 14-31 Oligopoly • If the oligopoly industry output is subject to a tax, the firms will reduce their output. • But the firms normally over-produce (exceed the cartel share) so the tax will move them closer to the cartel solution. • Their before –tax profits actually increase. • However, it is possible for the firms to become worse –off. 14-32 Profits Taxes • Economic profit: the return to the owners above the opportunity costs of all the factors used in pdn. • A tax on economic profits is born by the owners of the firm. • Under perfect compn a proportional tax on economic profits changes neither MC nor MR. • No firm has the incentive to change its output decision. 14-33 Tax Incidence and Capitalization • Capitalisation: is the process by which a stream of tax liabilities becomes incorporated into the price of an asset. • Suppose the annual rate of return of land is $R0 this yr. The rental will be R1 next yr and R2 after 2 yrs and so on. Under perfect compn the price of the land is the present discounted value of the future streams of returns. If the interest rate is r, then the price of land PR is •PR = $R0 + $R1/(1 + r) + $R2/(1 + r)2 + … + $RT/(1 + r)T 14-34 Tax Incidence and Capitalization • If a tax $ui is imposed for i=0,1,2,…,T. Since land is fixed in ss the ss curve is vertical, the owner of the land bears the whole tax. • The landlord’s return falls by the full amount of the tax. The after tax value of the land will be: • PR’ = $(R0 – u0) + $(R1 – u1)/(1 + r) + $(R2 – u2)/(1 + r)2 + … + $(RT – uT)/(1 + r)T 14-35 Tax Incidence and Capitalization • The two expressions above show that the value of the land will fall by: • u0 + u1/(1 + r) + u2/(1 + r)2 + … + uT/(1 + r)T • At the time of the tax the price of the land falls by the present value of all future tax payments. • Capitalization complicates attempts to assess the incidence of a tax on a durable item that is fixed in ss. 14-36 General Equilibrium Models • Partial equilibrium: – Are simple and uncomplicated. – They give an incomplete picture • E.g. a tax on cigarettes affects consumers, farmers and the farm pdn pattern and prices of other crops. • General equilibrium analysis takes into account the way in which various mkts are interrelated. 14-37 Tax Equivalence Relations • Thousands of different commodities and inputs are traded, so how can we keep track of their complicated interrelations? • Useful results can be obtained from GE models with 2 commodities [food, F and manufactures,M],2 fops(K and L) and no savings. 14-38 Tax Equivalence Relations tKF = a tax on capital used in the production of food tKM = a tax on capital used in the production of manufactures tLF = a tax on labor used in the production of food tLM = a tax on labor used in the production of manufactures tF = a tax on the consumption of food tM = a tax on consumption of manufactures tK = a tax on capital in both sectors tL = a tax on labor in both sectors t = a general income tax 14-39 Tax Equivalence Relations • The 1st 4 taxes are levied on a factor in only part of its uses – partial factor taxes. • Certain combinations of these taxes are equivalent to other ad valorem taxes outlined above. E.g. a similar tax rate is applied on food (tF ) and manufactures (tM) , these are equivalent to an income tax (t), becoz they both create a parallel inward shift of a consumer’s budget constraint. • A proportional tax on both capital and labour is equivalent to an income tax. 14-40 Tax Equivalence Relations • Partial factor taxes tKF and and tKM tLF are equivalent to and and tLM tF and are equivalent to tM are are are equivalent equivalent equivalent to to to tK and tL are equivalent to t Source: McLure [1971]. 14-41 The Harberger Model: Assumptions Technology: • Assume 2 factors (K and L) • The model assumes constant returns to scale , although production techniques may differ across sectors. • They differ w.r.t • Elasticity of substitution (the ease with which one factor can be substituted for another) • Capital intensive (capital –labour ratio is high) • Labor intensive (capital –labour ratio is low) 14-42 Assumptions Behavior of factor suppliers: • Suppliers of K and L maximize returns. • K and L are perfectly mobile across sectors • Net marginal return for all factors in each sector is the same. Market structure: • Firms are competitive, profit maximisers, and all prices are perfectly flexible. • There is full employment of factors • Each fop is paid the value of its MP. 14-43 Assumptions Total factor supplies: • Amounts of K and L are fixed. Consumer preferences: • Consumers have identical preferences • Focus is on taxes effect on the sources of income. Tax incidence framework: • The model uses differential tax incidence analysis. The model considers the substitution of one tax by another. 14-44 Analysis of Various Taxes Commodity tax (tF) • A tax on food causes the relative price to increase. • Consumers substitute manufactures for food. • Food pdn falls=> K and L moves to manufacturing=> relative prices of K and L changes. • If food is a K-intensive sector, more K should be employed in manufacturing, if the relative price of K falls. • In the new position all K is relatively worse off. 14-45 Commodity tax (tF) • A tax on the output of a certain sector induces a decline in the relative price of the input used intensively in that sector. • This result will depend on the elasticity of dd for food, difference in factor proportions and the difficulty in factor substitution. • On the sources side, a food tax will hurt those who receive proportionately more income from capital. • On the uses side those who consume proportionately more food would bear larger burdens • Total incidence- a capitalist who eats a lot of food is worse off on both counts. 14-46 Income tax (t) • Since factor supplies are already fixed , this tax cannot be shifted. It is borne in proportion to people’s initial incomes. • Factors bear the full burden. General tax on labor (tL) • It is a tax on labour in all its uses. • There are no incentives to switch labour use between sectors. • Labour bear the entire burden. Partial factor tax (tKM) • Output effect: the price of manufactures tend to rise and the quantity demanded decreases. • Factor substitution effect: Producers use less K and more labour. 14-47 Partial factor tax (tKM) • If the manufacturing sector is capital intensive, the relative price of capital falls. • If it is labour-intensive, the relative price of capital rises. • The factor substitution effect leads producers to use less capital and more labour, leading to a drop in the relative price of capital. • If the manufacturing sector is K intensive both effects work in the same direction, and relative price of K falls. • If the manufacturing sector is labour intensive, the final outcome is ambiguous. • More generally, as long as there is factor mobility between uses, a tax on a given factor in one sector is ultimately affects the return to both factors in both sectors. 14-48 Some Qualifications Differences in individuals’ tastes: • When consumers have different preferences for the 2 goods, tax-induced changes in the distribution of income change aggregate spending decisions, relative prices and incomes Immobile factors: • For technical or institutional reasons some factors maybe immobile. If the taxed factor is immobile the factor bears the whole burden. 14-49 Variable factor supplies • In the LR the supplies of both factors are variable. • If there is a tax on K, in the SR the tax is borne by capital owners. In the LR less K will be supplied due to the tax. • The K/L ratio decreases and the return to labour falls becoz it becomes less productive. 14-50 An Applied Incidence Study 14-51