MNC's & FDI - WordPress.com

advertisement

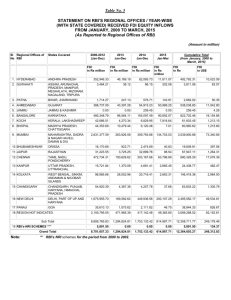

MNC’s & FDI What is MNC’s ? The multinational corporation (MNC) is the agent of international production. (Sometimes the MNC is called a transnational corporation or TNC.) International production is defined as “that production which is located in one country but controlled by a multinational corporation (MNC) based in another country”. (Cantwell, 1994). Thus, an MNC is a corporation that carries out production activities in more than one country. In particular, it controls the assets and manages the production activities in one or more foreign countries. To do this, a corporation based in the home country must own and operate plants in one or more foreign host countries. Foreign Direct Investment To obtain plant and other production facilities in a foreign countries, an MNC must invest. Thus an MNC has to be a foreign investor. These investment activities show up in the annual statistics of the home country and the host countries as “foreign direct investment”. Government regulation of MNCs as such is carried out mainly through regulation of foreign investment activities at the time the MNC seeks to make a foreign investment. Foreign direct investment is the acquisition of assets in which the foreigner has a controlling interest. Portfolio investment is the acquisition of assets in which the foreign investor does not have a controlling interest. The US convention, followed by Australia and a number of other countries, defines “foreign direct investment” as ownership of 10 per cent or more of the ordinary shares of voting stock in the corporation. This known as the “10 per cent rule”. It is a rule of thumb. Foreign direct investments may be divided into two principal types : greenfield investments, i.e. the construction of new plant and facilities Mergers and acquisitions, i.e. the acquisition of foreign assets by means of purchasing existing plants and facilities previously operated by other corporations In recent years, FDI is about equally divided between these two forms There are other forms of cross-border investments, for example,direct acquisition of plant and facilities of stateowned enterprises when these are privatised Joint ventures Strategic alliances – these are agreements with other corporate partners (either from the host economy or a foreign country) that do not involve money transfers on the part of the foreign partner(s) Infrastructure build-own-operate-transfer (BOOT) agreements in which a foreign partner builds and operates infrastructure facilities for a limited period, with ownership and control returning to the government of the host economy. Eg the CityLink highway project in Melbourne. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) where one or more of the private partners are foreign investors. FDI statistics are recorded in two forms: Flow statistics. These are the annual values of new foreign direct investment Stock statistics. These are the accumulated value of all past investments. Here one needs to include the value of all of the earnings of the foreign subsidiary or affiliate which are reinvested in plant, facilities and other assets, rather than being distributed as dividends to the parent corporation(s). Global distribution of FDI UNCTAD estimates that there are about 77,000 MNCs with about 770,000 foreign affiliates. Slides on UNCTAD statistics The World’s top 100 non-financial TNCs Many of these have production activities in many countries eg Royal Dutch/Shell has operations in more than 130 countries Transnationality indices for individual corporations, and aggregates for host economies Modes of Entry into Foreign Markets When a corporation based in one country wishes to enter or expand its corporate sales in another country, there are alternative modes of entry: exporting from the home country, i.e. the production facilities remain in the home country international production via FDI There are other ways joint ventures, strategic alliances and other agreements in which the parent company is a partner in production but does not have a controlling interest licensing agreements, franchising and other contracts in which a foreign partner (s) or franchisee is the producer Choice of Mode There is a large management literature on the factors which determine the choice of mode. This the subject matter of Business Strategy courses. As a part of this, there is a sub-literature on the theory of FDI. There is no universally-agreed theory of FDI. Obviously, the decision to enter a foreign market by the mode of FDI is affected by many things: commercial and sovereign risks, technologies, market access, tax liabilities, etc. Dunning’s OLI paradigm The basic rationale for all FDI is to increase or protect their profitability, that is, to increase the capital value of the firm. The most popular model is that of John Dunning. This is known as the “eclectic” paradigm as it is a composite model. The OLI paradigm argues that a corporation uses direct entry via FDI as the preferred mode if it It has an Ownership Advantage, e.g. a patent or other intellectual property, and It has a Location Advantage in the host economy, eg large domestic market or low production costs, and An Internalisation Advantage, i.e. it is better to undertake production itself Such FDI will increase the capital value of the foreign-investing corporation. Other theories of FDI The Dunning model is an example of what are sometimes called “asset-exploiting” theories. There are other theories which emphasis “assetaugmenting” FDI. In contrast to asset-exploiting strategies, these models emphasize that firms may undertake FDI in order to acquire created assets such as technology, brand names, distribution networks, etc which other foreign firms have already build up. We will not pursue further the theory of FDI as we are chiefly interested in the role of government in permitting or regulating international business Are International Production and Trade Complements or Substitute? We should not regard the modes as simple alternatives as the relationships may be more complex. These two modes of supply may be complements rather than substitutes, i.e. an increase in FDI may lead to an increase in trade in goods or vice versa. This can happen in a number of ways. For example, establishing a foreign affiliate may lead to new trade in parts, components and intermediate and capital goods between the parent investing corporation and the affiliate. In fact, there are complex links between the investing and trading activities of a corporate group, eg global production chains. How Governments Regulate FDI National government regulate the entry and the production activities of foreign investors (MNCs) in many ways: 1. Restrictions on Market Access 2. Rights of establishment notification/screening estricted/closed/priority sectors conditions eg joint ventures, minimum domestic shareholding/maximum foreign shareholding Investment protection – Host country obligations 3. expropriation – circumstances, compensation transfer and repatriation of funds Intellectual property protection source country actions investment guarantees Controls on the Movement of natural persons entry, residence and work permits for foreign workers How Governments Regulate FDI Continued II National Treatment domestic laws, regulations, policies performance requirements – labour training, trade-related requirements (TRIMS) III FDI Incentives Most governments today have few controls on the exit of capital to other countries, except for some attempts to regulate bribery and corruption involving home country investors and host economy governments and, in developing countries, foreign exchange limits on foreign investments. Hence, most of the controls or restrictions are imposed by the host country governments Views of MNCs Whereas 30 or 40 year ago many countries, Developed as well as Developing, were suspicious of FDI and regulated it heavily, FDI has, especially since about 1985, come to be regarded as a positive factor in the host economies. In particular, foreign investors are seen today by economists and governments as agents of technology transfer and business organisational improvements. One should not fall into the opposite trap and regard all FDI as benign. One senior executive of GM in the USA once famously remarked that “ What is good for GM is good for the country.” This is palpably wrong. Host economies must guard against anti-competitive behaviour, tax evasion, adverse effects of production on the environment and other harmful effects of some MNC actions. There has been a recent counter-movement among NGOs which is highly critical of MNCs on particular issues such as the need for codes relating to labor standards (“sweatshops”), corporate governance, actions that affect the environment attacks on biotechnology, eg.movements to ban GM technologies criticisms of pharmaceutical corporations and patented drugseg compulsory licensing in the WTO